One of the most controversial figures of our time is coming to town. Notoriously elusive, this woman of a certain age rarely makes public appearances, so you can be sure that when she arrives in Houston this month there will be no lack of wagging tongues. But this is not some reclusive celebrity we’re talk-ing about. This world-famous lady is Lucy, a most gossip-worthy fossil.

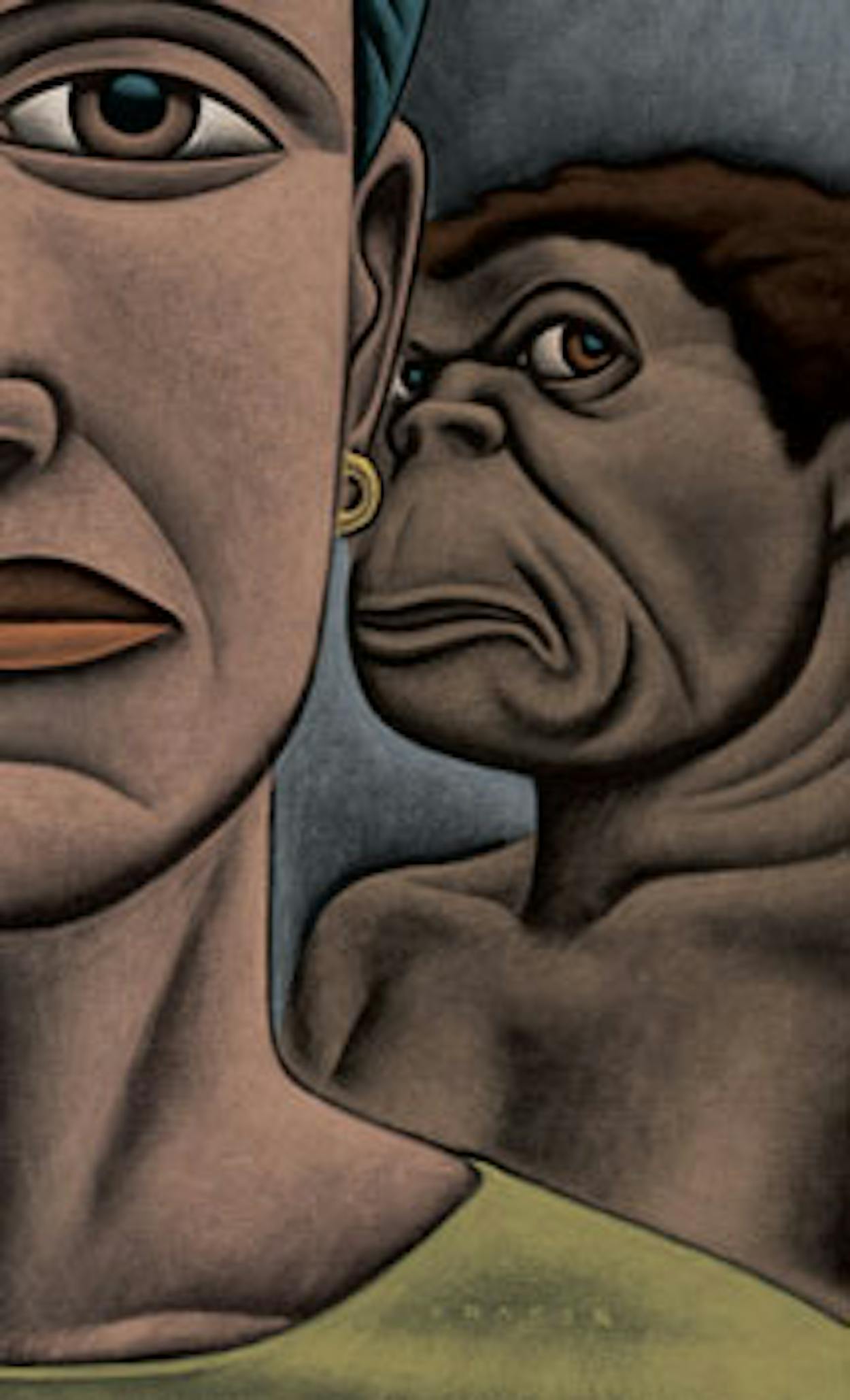

As any science buff knows, Lucy is the 3.2- million-year-old hominid who was discovered in Ethiopia in 1974 and who promptly became a household name as one of the oldest and most complete of our human ancestors ever found. Now, in an unprecedented (and hotly disputed) move, the Ethiopian government is sending the fragile relic, which has been on public display only twice before, on a proposed six-year, ten-city tour of the United States. Our own Houston Museum of Natural Science has been selected as the stateside organizer of—and the opening stop for—the resulting exhibit, “Lucy’s Legacy: The Hidden Treasures of Ethiopia.” The show will include a hundred or so other ancient artifacts, but there’s no doubt as to who’s the star. Lucy is, after all, at the crux of the where-do-we-come-from debate and for years has set evolutionists and creationists at odds over how old she is, whether she could walk upright, and whether she is any more closely related to humans.

This exhibit won’t exactly settle those arguments. In fact, it raises yet another divisive squabble: Should such a delicate old gal even be traveling at all? Even though Lucy will be flying first-class in a specially made suitcase, critics say that she is too valuable for such an extended vacation and is likely to be damaged. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History is one of several institutions that have declined to host Lucy (says an official there: “We don’t think it should leave Ethiopia”), and prominent anthropologists have gone so far as to call the tour scientifically irresponsible. But HMNS’s curator of anthropology, Dirk Van Tuerenhout, insists his museum shares the safeguarding concerns over such precious cargo. He points out that conservators both here and in Ethiopia concluded that the bones could travel, and he ticks off a list of other invaluable objects (King Tut’s mask, the Dead Sea Scrolls) that have been sent around the world. And considering what Lucy was probably exposed to before she was dug up a mere three decades ago—floods, earthquakes, droughts, errant elephants—we’re lucky to have her at all. “What more powerful way to present the story of mankind than by having an original fossil on display?” he says.

Regardless of your beliefs about evolution, and no matter where you stand on the access-versus-preservation issue, “Lucy’s Legacy” offers an extraordinary look at the culture and history of the Cradle of Mankind, aspects so often obscured by the negative images of war and poverty. Though Lucy is merely a speck in Ethiopia’s storied past (other treasures you’ll learn about in the exhibit include the country’s eight-hundred-year-old churches carved out of rock, traditional handwritten manuscripts, and some of the largest single-stone obelisks ever made), she is being sent as a sort of goodwill ambassador on behalf of her homeland. As so many of today’s celebs-turned-diplomats have learned, that’s not a bad way to garner a little publicity. Read and interview with Dirk Van Tuerenhout. Aug 31—Apr 20. 1 Hermann Circle Dr, 713-639-4687, hmns.org