This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Railroad commissioner Mack Wallace is the only elected state official who is better known in Tel Aviv than in Texas. A gusher of newspaper clippings, pamphlets, reports, statistics, newly minted colloquialisms, quotations from old speeches, and dire warnings, Wallace has entered international politics in an attempt to forge an alliance between Texas and Israel. The panoramic view of the Capitol from his office at the William B. Travis State Office Building is overwhelmed by what could be called the Maps of Doom, two 4- by 6-foot maps covered with numbers and dots and straight and broken lines. The maps illustrate the world’s oil reserves and shipping and pipeline routes; they are not meant to bring peace of mind to the citizens of the United States. And Mack Wallace will tell you that unless we change our national energy policy now, unless we get a national energy policy now, we are headed for a hydrocarbon apocalypse.

For decades various Texans—most traditionally, independent oilmen—have been forecasting the imminent destruction of America’s domestic petroleum industry and the resulting suicidal dependence on Middle Eastern oil. But originality is not Wallace’s concern. His concern is that now, as the rest of the country slumbers under the delusion that OPEC is broken and that we have reinherited our birthright of cheap oil, the destruction—really and truly this time—is coming to pass.

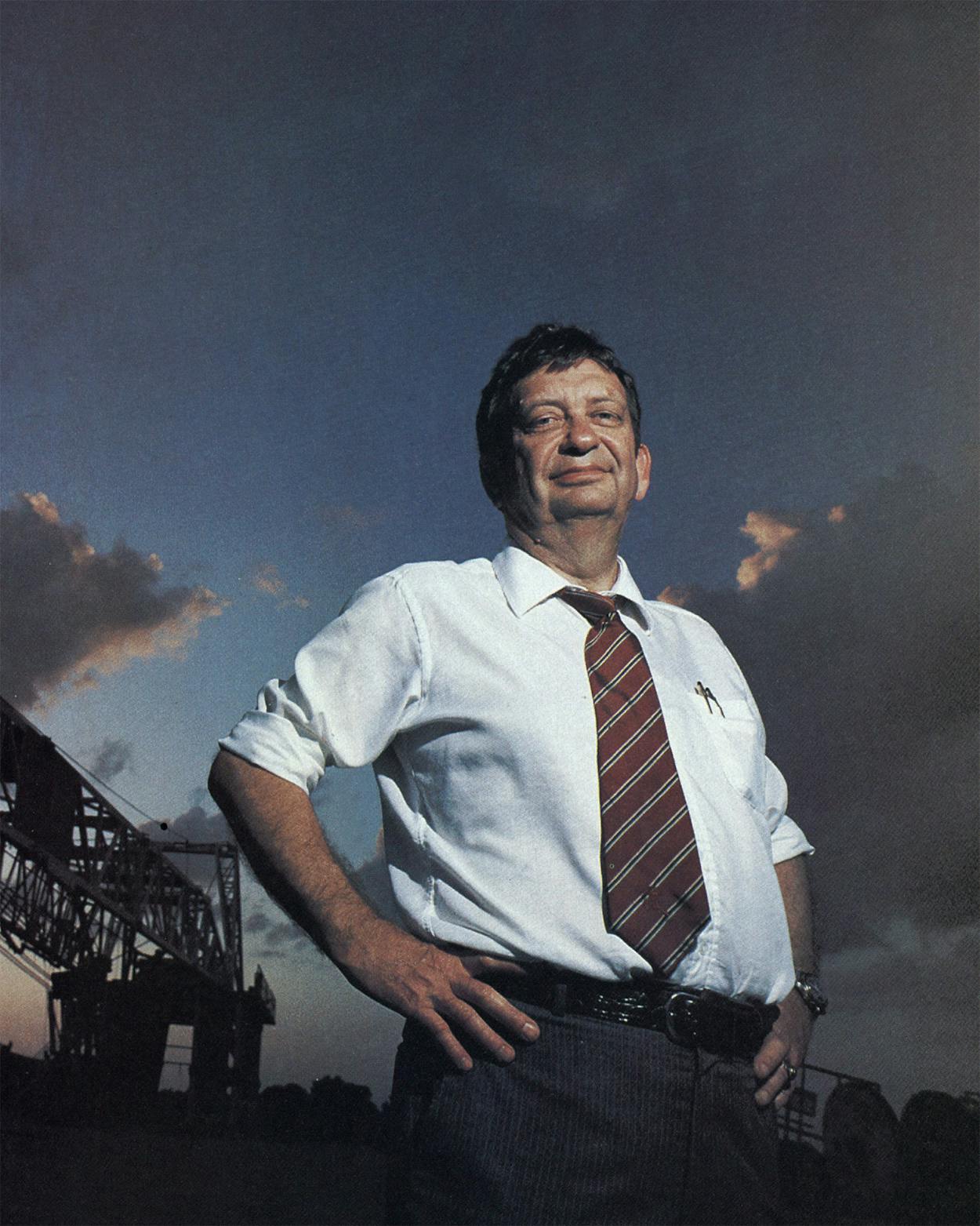

Wallace, who was appointed to fill a vacancy on the Railroad Commission of Texas in 1973 and has since been elected to the office three times, is an affable, rumple-faced former district attorney who believes that destiny has thrust him into the role he is playing (“If not me, who?” he asks). It is only fitting that he was born in Athens (Texas), because Wallace is a modern-day version of Cassandra, the mythical Greek figure who foresaw visions of destruction but was condemned never to be believed.

As former railroad commissioner William Murray says of Wallace, “He ain’t just working for the economy of Texas. He’s working to save the country. But it may be falling on deaf ears.”

The job of railroad commissioner is guaranteed to lift the officeholder out of the ranks of the unknown into those of the obscure, so Wallace has sought a broader forum from which to spread his message—and to spread it to people who count. Last year he found that forum in the Council for a Secure America, an organization composed primarily of two unlikely allies: independent oil and gas people from the Southwest and Jewish business executives from the East Coast.

The council began as the brainchild of Congressman Tony Coelho, a California Democrat who heads the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. Coelho is considered a shrewd issues man, and he saw what no one had seen before, and many still don’t: the two groups have a strong mutual interest—a concern about Arab control of oil. The political theory behind the coalition is simple. If northeastern representatives and senators vote for tax breaks for the oil and gas industries, then legislators from producing states will cast pro-Israeli votes.

Wallace was introduced to Coelho and the council by Charles Perry, a natural gas company executive from Odessa who knew of Wallace’s international interest. The council was formalized in March 1985 with Wallace as cochairman. His counterpart, Selig Zises, is the head of Integrated Resources, a New York–based tax-shelter marketing firm. Texans on the council board include Perry and oilmen George Mitchell, L. Frank Pitts, and Marshall Brachman.

When Wallace explains the connection between the two groups that make up the council, he does so with the manner of a florist explaining why he is in favor of Valentine’s Day. “The security of Israel is important to the free world. The ability of the U.S. to produce oil and gas is important to the free world. Out of that idea was set up an education organization to bring congressmen from the Northeast to Texas and Oklahoma and other producing states,” he says. “The counterpart of that is taking congressmen on trips to Israel, where we would discuss the needs of Israel, and we would each have access to the other’s delegations. That’s what it is, and that’s what we’re doing.”

The council’s $280,000 budget is paid for equally by oil-producer members and by what council literature refers to as “friends of Israel.” The council is officially an educational organization, and to keep its tax-exempt status, it is not allowed to engage in lobbying. But a few press stories have painted the council as just another special-interest group looking for tax breaks, an interpretation that infuriates Wallace.

“If we need it to survive, it’s not a special interest—it’s a national interest!” Wallace says. For him, tax breaks are as essential to energy independence as drill bits. Though he leaves the details to others (“I’m not a tax person. I’m concerned with energy independence. That’s all there is to it”), he believes that it’s the place of government to do for the oil business what private enterprise can’t. “If you want an industry for strategic reasons, you need a subsidy. Private enterprise can’t do it. The role of private industry is to make money. Government’s role is to provide defense, national security. It’s so plain, it’s frustrating to talk about.”

Wallace, who is 56, did not start out life with an ambition to save the world. His origins, he is fond of pointing out, are humble. “I was born in the same house in the same room my mother was born in,” he says. That was in Athens, where his mother still lives. His father was a clothing manufacturer’s representative—a traveling salesman—and his mother a medical assistant. One of Wallace’s early jobs clearly influenced his worldview. As a teenager, he ran a movie projector at the local theater. “I like those old cowboy movies. You know who’s good and who’s bad,” he says. “There’s no gray.” Today he has a collection of some of the John Wayne films he showed back then. “They all exemplify duty. Duty for a cause. Whoever said ‘duty’ was the most sublime word in the English language hit it.”

Wallace attended Henderson Junior College, from which he received an award as outstanding ex-student in 1974. The plaque hangs in his office today. “It’s not something to do with my international interests, but it means a lot to an old country boy like me,” he says. At age eighteen he enlisted in the Texas National Guard. “I grew up in the Texas National Guard. I spent fifteen years in it. I was discharged as a captain. I served in the artillery and with administration in the division staff. It was integral to my personality.” After junior college he went on to Baylor University, where he majored in history and received a law degree in 1953. He had decided as a high school student that he wanted to be a lawyer, but his were not visions of a lucrative partnership in a swank firm. “I’ve always been interested in law enforcement,” he explains. “I am at this moment a certified Texas peace officer.”

After four years in private practice, Wallace ran for the office of Henderson County attorney and in 1957 was elected to the post. Five years later, he won the race for district attorney of the Third Judicial District and served in that office for ten years. Although his duties as an East Texas DA did not offer much opportunity for involvement in international geopolitical affairs, he believes that his years as a prosecutor helped prepare him for his concerns today. “Those years taught me to look at facts and come to conclusions and present those facts in a logical manner,” he says.

He then got involved in Dolph Briscoe’s successful gubernatorial campaign, and in 1973 Briscoe appointed him executive director of the Criminal Justice Council. That was a big year for Mack Wallace. By September, Briscoe needed someone with no ties to the oil and gas industry to fill a recently vacated railroad commission office, so he appointed Wallace to that hot seat. The three commissioners were embroiled in one of the agency’s biggest controversies—the Lo-Vaca case, in which a natural gas company found itself unable to honor contracts that supplied natural gas to about a third of the state’s population. If that wasn’t enough, one month after Wallace’s appointment, the Arab oil embargo began.

“I saw the commission being accused of creating the world oil shortage,” he recalls. “That set me to the historical mode. I stayed up nights studying.” One of his sources was the speeches of a predecessor on the commission, Lieutenant General Ernest O. Thompson. During his tenure from 1932 to 1965, Thompson was the commission personified.

Wallace reaches into an overstuffed accordion folder and instantly puts his hand on the piece of paper he wants. “This is what General Thompson said on June 23, 1953: ‘We must never be at the mercy of foreign oil.’ ” Wallace takes off his half-frame glasses and waves them in the air for emphasis. “That man is entitled to recognition for having been right. When I went into this thing, I was working a lot on instinct. History has justified my position.”

Whatever history’s verdict will be, the predictions have not changed substantially in the past few decades at the railroad commission, an agency that regulates surface mining, intrastate trucks and buses, and oil and gas production and transportation. In the name of conservation, the commission managed to restrict Texas’ production of oil from the thirties to the early seventies through a process it called prorationing, thereby keeping oil prices artificially high.

What offends Mack Wallace is that OPEC understood the commission’s lesson and applied it all too well. It’s one thing when the people deciding the price of crude are elected officeholders of the State of Texas. It’s another when they are Arab oil ministers. “What the Saudis are trying to get is what they think they learned from the Texas Railroad Commission—worldwide proration. They took a plan we put in place for conservation and are using it for political purposes,” Wallace says.

Despite Texas oilmen’s patriotic condemnations of OPEC’s economic blackmail, the cartel was one of the best things that ever happened to them, and there are those who say that the best thing the federal government can do now is just what it’s doing: nothing. Let gas consumption go up, let oil imports rise, let the Saudis jack up the price again. Replay the scenario of the seventies; it made a lot of Texans rich once. Well, Mack Wallace has a message for people who think like that. “You cannot wave an eggbeater in the air and get oil out of the ground!” he says. “Producing oil takes an infrastructure that requires training, experience, and dedication, and if we lose that infrastructure, we cannot re-create it!”

The necessity of explaining that simple fact to Yankees who probably believe in the eggbeater theory of crude production led Wallace to the Council for a Secure america. “The sad thing is this regional warfare,” he says. “That’s why we work so hard to get congressmen down here.”

Good explanations for an alliance do not necessarily translate into an effective alliance, and convincing people of what Wallace sees as a self-evident mutuality of interest will be a major undertaking. On one hand, the plight of oil producers does not evoke the same level of sympathy engendered by, say, disabled veterans, so persuading members of Congress from consuming states to take a concerned look at the industry won’t be easy. On the other hand, members without substantial Jewish constituencies may not be inclined to support Israel, since that often means voting for foreign aid and against lucrative arms sales to Arab states.

It is difficult to see how the council’s spring trip to Israel will result in legislative action for domestic oil producers. But Wallace’s advocacy of Israel is more than a matter of defense or political strategy; it is one of visceral identification. “The Israelis have done a magnificent thing against almost unbelievable odds. The nation has been at war since its existence, and it has survived. Adversity breeds strength,” he says.

On that most recent field trip, council participants met with Prime Minister Shimon Peres and members of the parliament, among others. The Israelis also provided activities guaranteed to get the adrenaline of a retired Texas National Guard officer pumping. “We visited with an armored unit in the general area of the Golan Heights. Several of us had the opportunity to fire the Galil assault rifle, which was an experience for all of us,” Wallace says. “It’s a shoulder-fired rifle. It’s the Israeli answer to the AK-47. Then we visited an Israeli Air Force base near Tel Aviv, where they simulated a scramble—that’s what happens when intruders cross into Israeli airspace.”

The Council for a Secure America has taken Wallace into territory that might be considered even more dangerous than the Golan Heights: the editorial board of the New York Times. Before the council was officially organized, Howard Squadron, a New York attorney who is now a member of the council, arranged for Wallace to take his message to the people who write the New York Times’s editorials. What Wallace did was give them a version of The Speech—his discourse on the dangers we face. The speech can run from ten minutes to a politburo length of three hours. The core of the speech is a series of recent newspaper clips whose headlines read in sequence: Oil Future Hinges on Saudi Power . . . White House Abandons Goal of Energy Self-Sufficiency; U.S. to Depend on Arab Oil . . . U.S. Seeking to Forestall World Oil Crisis . . . and finally, Saudi Sees Arab Oil As Political Weapon by 1987.

“My presentation is logical—one, two, three, four, five. That’s what makes it so devastating. It is logical, based on fact,” Wallace says. He told the board that to avoid disaster, the country needed a tax on imported oil. “I said prices will go up, but in the long run it will give you a domestic production capacity that will shield you. Seventy-five per cent of the crude oil in the world is produced by governments, not oil companies. That in and of itself makes crude oil an instrument for foreign policy.

“I laid all this out. Frankly, based on the length of the interview and the questions they asked, I had some concern that I was able to make the point.” Wallace rummages on his desk and pulls out a copy of a newspaper clipping. He holds it up with undisguised glee. “In February they came out with this lead editorial. They recommended a ten-dollar-a-barrel tax,” he says. “I was only asking for five.”

A call to the newspaper to confirm Wallace’s role in the editorial board’s thinking ends up revealing only how close-lipped the board can be. An assistant to Max Frankel, editorial page editor of the Times, commented on Wallace’s visit: “Mr. Frankel said it was interesting. It was one of many such meetings. What influence he had on our editorial position I cannot say.”

It’s Monday at the railroad commission, which means it’s conference day, when hearing examiners present their findings to the commissioners for a decision. Should someone’s leaking oil well be plugged? Can a different recovery method be used in a given field? Sitting there on a Monday morning in a room ringed with portraits of past commissioners, you can see why—unless it’s your well that’s being plugged—the commissioners and their duties remain remote to the public. A hearing regarding whether a trucker licensed to haul black plastic pellets might also be allowed to haul multicolored plastic pellets is only one example of how arcane the commissioners’ work can be. Wallace says he doesn’t mind. But such daily duties make it a little easier to see why Mack Wallace, railroad commissioner, has taken on the additional role of Mack Wallace, international statesman.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Energy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin