This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Up there where Main Street begins somebody had done a good job of flattening a grackle with an automobile. It floated in a mud puddle with its wings outspread, so dense and black it could have been a piece of hot tar that had fallen into the water and accidentally congealed into the shape of a bird.

I was standing in the same puddle, having been forced off the narrow street by the traffic, which even here at the origin of Main was fierce. The asphalt was uneven—it seemed to be a work of nature, like a lava flow—and along it caromed a succession of pickup trucks loaded down with engine blocks and odd bits of chrome, as well as lurching, rusting ocean liners with dashboard shrines.

It was my notion to walk the length of Main Street, from this drab little spot six miles north of downtown Houston all the way through the city limits to the street’s anonymous terminus far out on the coastal prairie. To be sure, Main had its shopworn stretches, but its dimensions were still epic. It cut through the city cleanly, and you knew it led somewhere. A driver, after experiencing the orbital mechanics of Loop 610, could pull onto Main and feel that his tires were touching solid earth again. It really was the main street. A faithful observer, I reasoned, could expect to encounter a good part of the spectrum of human activity there: he could expect to see the main things. That was why I had proposed to travel by foot. But now, after I had taken only a few steps, it was clear that such a project went against the very warp and woof of the city. Walking the length of Main Street would be like rollerskating over twenty miles of arctic tundra.

Nevertheless, I picked my way through the water and debris on the side of the street and headed south. I could see downtown in the distance, or at least the sickly green sheen of the Allied Bank tower, a half-completed glass skyscraper that looked as if at any moment it might shatter like a wine glass.

All that commerce, all that busy money, was light-years away from North Main. But the street had been viable once. Some say this was the road Sam Houston’s army traveled on its feinting retreat before Santa Anna. Much later, North Main was known as Montgomery Road, and as Highway 75 it ushered northbound traffic out of town. But the building of Interstate 45 promptly made the old highway obsolete, and now in its upper reaches Main was lined with sagging, unpainted shacks that might still house a beauty parlor or a barbecue joint but were most often abandoned.

Technically North Main is not quite kin to the wide thoroughfare that Gail Borden designated as Main Street when he laid out the town on the south side of Buffalo Bayou. North Main remained Montgomery Road until a bridge was built across the bayou, when the name was changed by fiat. But it fits well enough. The street’s faded hegemony meshes with the ambience of the ancestral Main across the Bayou, and along it you have a sense—rare in Houston—of geographical grounding. If the city has spread aimlessly over the landscape like some great river in flood, Main Street is still the river channel itself, the course to which the vast boom town has more or less hewed.

Except for the traffic flow, the street was almost abandoned. The prosperous-looking churches were locked, and the young men loitering outside a nameless, windowless grocery store looked so disengaged that Sam Houston’s army could have reappeared out of the ether and marched down Main Street again without their notice.

Subtly the street changed from black to Hispanic after a few blocks in which the ethnic stamp was murky. It was Loop 610 that defined the difference as much as anything, and after that the neighborhood was a little sprightlier, the street a little wider and lined with bridal shoppes, taquerías, discotecas, coctelerías.

On the other side of 1-45 stood the Hollywood Cemetery, an old, lush place where I imagined the bones of the nineteenth-century dead rattling in resonance with the vibrations from the freeway. Greeting the visitor was a statue, serene figure in a robe glancing down at beseeching child. I was taken aback to find the lyrics to “The Eyes of Texas” carved into the stone at the base of this statue, but on reading further I discovered that the child represented “the young Texas youth” and that his companion was the angel Gabriel. This youth, read the inscription, was seeking “guidance and direction of Texas destiny.”

A few blocks south I made a slight detour onto North Street to get a closer look at a tower I had seen rising above the tree line. The thing was a good six stories high, a four-sided pillar on which was balanced a flat, square structure that reminded me of a cereal box lying on its side. The tower rose from the grounds of a company called Metal Enterprises, and there was a sign on the high fence outside that said, “Notice to thieves: I intend ‘to shoot’ the next bastard who climbs my fence.”

“That’s my home,” R. W. Walker replied when I went into the office and asked what the tower was for. When he had determined that I was not one of those fence-climbing bastards, he swung his lizard-skin cowboy boots off his desk and took me up to see it. Walker explained, as we entered a door in the base of the tower and rode upward in an elevator the size of a shower stall, that he liked to stay on the premises at night. He had thought about building a place on the ground, but he figured he might as well have a view. So eight years ago he began construction. mostly working entirely by himself, and after two years Raven Tower was completed.

The elevator door opened before a picture window in which downtown Houston was prominently displayed. Inside, Raven Tower had the classic look of a bachelor pad: a vivid burnt orange carpet, a stuffed iguana, a gumball machine, two security monitors on top of a television that swiveled within its wall frame so that it could face either the bedroom or the living room. There were any number of stuffed ravens, as well as a small, low-slung dog named Cleo. On the walls were large pictures of prowling tigers and owls, painted with a material as thick as candle wax.

“They’re on velvet,” Walker explained. “But the paint is more of a poured deal. Only one guy in the market in Laredo had them.”

Walker’s tower looked out over Little White Oak Bayou, which from that high perspective was a pleasant little trough of greenery. When I continued my walk, though, I was saddened to see that from street level it was nothing better than an urban gulch. It looked like it had been gouged out of the ground with a backhoe. The bayou was filled with tires and old appliances, and a shopping cart lay overturned in the center of the stream, creating little braids of current when the water flowed through its mesh.

The Salvation Army’s Harbor Light Center was just ahead, a three-story structure surrounded by a high chain-link fence. At this hour of the day it was nearly empty, but by around four-thirty, said its director, someone would have claimed each of the vacancies in the sea of narrow beds that covered the third floor.

Most of the clientele were young men, industrial workers from the North who had come to Houston in time for the door of opportunity to shut in their faces.

“Right now I’m just waiting around for eleven a.m.,” Wayne Locke told me. He was sitting in the TV room, where rows of perky plastic chairs faced a sober wall-mounted television. He was 24, with a pale complexion and a just-noticeable fringe of beard. “When it’s eleven a.m. I’m going to slip off to the plasma center, get a little pocket change. They take a full pint there and give you six dollars. What they do is they draw a pint out, take it back to the centrifuge, extract the plasma, and bring your cells back to you. Hell, for six dollars that’s not bad.”

North Main became Main Street proper on the other side of Buffalo Bayou, just upslope from the dinky little park that commemorated Allen’s Landing. An early visitor to this place recalled that his boat missed the landing entirely, and only upon backtracking was he able to find footprints and other oddments of civilization that told him he had arrived at the city of Houston. Along the bayou the foliage was still thick enough to allow one to believe that such a wilderness had once existed, with clear water and torpid cottonmouths dangling from the overhanging limbs. Downtown, though, that feeling for the natural groundwork of Houston vanished utterly.

In harmony with the bayou, the streets of downtown Houston were laid out in catawampus fashion, so that the longitudinal streets ran northeast to southwest, rather than north to south. As a consequence, the whole city was a few degrees off kilter. Main was no exception, but the street was straight and broad and full of resolve, and if it veered from the magnetic poles you had the feeling it did so only because it found them trivial.

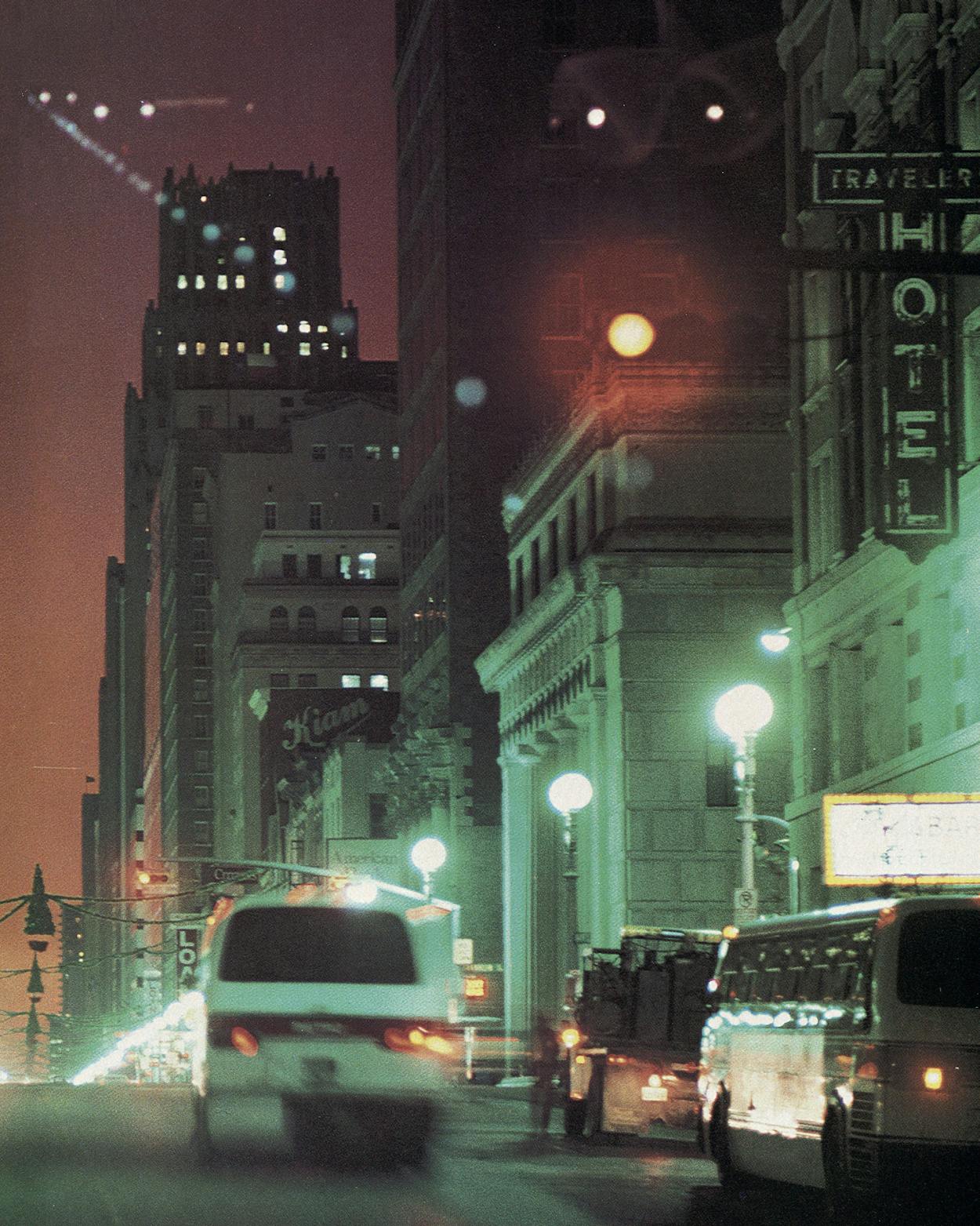

The old bank buildings still lined the street above the bayou, huge heavy-lidded structures with stalwart columns and busybody flourishes. They seemed to sag with responsibility, though most of the real money had moved off of Main Street and the old structures now housed wig shops and nude clubs. But the stateliness and grandeur had not departed entirely, and I thought the seedy surroundings set the hallowed buildings off nicely. A monumental hulk like the Rice Hotel, built on the site of the original Capitol building of the fly-by-night Texas Republic and abandoned in 1977, had such a gloomy, foreboding air that it looked like it might at any moment suction a hapless passerby into its maw and spit out his bones.

I was walking this part of Main with Frank Glass, of Spaw-Glass, a giant construction company headquartered in Houston. Glass is a small man with a confident bearing, and as he strolled down the street, his camera slung over his shoulder in case he wanted to take a picture of a building, he pointed out the structures that he and his investment company had restored or were planning to restore, as well as those that were scheduled for demolition.

“We’re restoring this hotel here,” he said. “And we’ve got this corner all the way to the Franklin Bank. Our plan is to restore the existing building and put a six-hundred-car parking garage behind it. We’ll build a twenty-story building in this slot here.

“All of this goes,” he said, indicating a good portion of the block across the street.

For the immediate present, though, Glass’ plans were in limbo. Lately the Metropolitan Transit Authority had been monkeying around with a proposal to put an elevated heavy rail line right down the middle of Main Street.

“It amounts to a negative environmental impact, is what it amounts to,” Glass said.

The models and artists’ renderings of the elevated had made it look picturesque: a futuristic train running fifteen to twenty feet above street level all the way down Main to Highway 59, with passenger stations along the way that were soaring domes of glass. That was all very well. But in reality the elevated would be a giant freeway built smack-dab on top of the street, hiding the architecture that Glass and his company were so busy preserving and creating a dim tunnel underneath.

Glass was not opposed to putting a subway under Main Street. He was not opposed to digging it, either, since one of the stockholders of Spaw-Glass owned a French construction company that specialized in subways. But that was not his motive in opposing the elevated; if it came to it, he’d bid on that. Once it was built, however, the ambience of Main, of the whole CBD, as he called the central business district, would be ruined forever.

I proceeded down Main Street, soaking up the ambience while it lasted. The environmental integrity did not cause my heart to skip a beat, but I thought it would be a shame to bury it all under a rail platform. I was not surprised to learn a few weeks later that the elevated idea had been scrapped.

The Gulf Building was the big display piece on this end of Main Street, a pull-out-the-stops art deco skyscraper built by Jesse Jones that was, for the twinkling of an eye, the tallest building west of the Mississippi. It struck me as a bit too titanic, and the bank lobby inside was so vast and ornate and hush-hush that it was impossible not to think of some crotchety old scrooge wallowing in a pile of gold coins in one of the back vaults.

Down the street I bought a raffle ticket from a member of the Pan African Orthodox Christian Church, who wore a lapel pin in the shape of a black dove. He said the money would go to buy computer keyboards for the church “to give the little children a background in programming.”

Businessmen walked briskly along, holding their suit coats closed against the gritty wind. In front of Foley’s a woman was trying to tell a man why she thought it wasn’t working out, but it was evident from the hurt, confused sound of his voice that he wasn’t going to allow her to let him down gently. In a little alcove between two buildings a sidewalk vendor had some mechanical dogs set up on a card table. They made a sound like grinding teeth. A flyer taped to the wall advertised an upcoming concert by the Gospel Truthettes.

The tall downtown buildings soon receded into the distance; I was in the lowlands now, on the part of Main that had once featured grand Victorian homes. But as Main had begun to assert itself as more of a thoroughfare and less of a residential street, the rich retreated into exclusive neighborhood burrows like Shadyside or Courtlandt Place. Now where those homes had stood were places like Rex’s Oriental Arts, which was packed with Bruce Lee memorabilia, and Filly’s Men’s Formals, where I was stopped in my tracks by a fierce-looking mannequin wearing a gray swallowtail coat and a hank of synthetic yellow hair and leaning forward in an aggressive posture with its teeth bared like an attacking primate.

Half of the stores in this block were vacant, their windows painted over with announcements of new locations and going-out-of-business sales. It was unclear to me whether these businesses were withering of their own accord, or if they were being crowded out by downtown’s manifest destiny. In any case Main Street would soon be without them, and all of a sudden I was struck by how transitory and thinly rooted even the most stalwart of these enterprises were. Main Street itself seemed permanent, a feature of almost geological scale against which all human activity was evanescent. I looked back up downtown and thought about how much had vanished without a trace: teams of oxen and mules, floods, brawls, gunfights, confectioners, milliners, touring opera companies, dry-goods dealers. Lamplighters used to walk around at dusk with long tapers, igniting gas lamps that were shaped like birdcages. Traffic patrolmen used to sit high above the street in towers, flashing semaphore signals to the motorists below. A thousand parades had passed down this street. At the head of the first one had been the grandiloquent Sam Houston, and the most recent had featured Kathy Whitmire, Houston’s new sobersided mayor.

Musing on these matters, I began to feel like Ecclesiastes. I sought comfort at the window of a Christian Science reading room. “The truth of being,” I read, “makes man harmonious and immortal while error is mortal and discordant.”

I, for one, couldn’t decide if this part of Main was discordant or just eclectic. At about the 2800 block the shops began to have signs like “Trung, Tam, Khai, Thue and Ke Toan—Income Tax and Accounting.” This was the Vietnamese commercial district, filled with herb shops, Indochinese restaurants, and an Oriental Super Center stocked with sweetened kumquats, sandals, bolts of cloth, and clocks in the shape of Viet Nam. Beyond that were the antique stores, porno theaters, fire sale stores, and—rising above it all as plain as an icon—a flagship-class Sears.

Then there was Golf Cars Unlimited, a showroom filled with customized vehicles that looked as tame as carpet sweepers. “On our cars,” the president, Bob Austin, told me, “we try to include everything a golfer could possibly want. The trunk converts easily to a golf mode, and when you lift the hood the whole front end is a cooler as big as a forty-eight-quart Igloo. This model is street legal. It’s got turn indicators, a radio, a heater, a fan.”

One of the cars—“cart” was not the industry’s preferred term—was a scaled-down fire engine, another was a knockoff of a Rolls-Royce. Clint Eastwood had sat in one of these cars, and so had Bob Hope and Gerald Ford. But these were not boom years for the golf car business. Austin could trace the decline to the oil glut. He figured that about two thirds of his customers were involved in the oil business, and as those royalty checks began to dwindle, customized golf cars were one of the first things to be cut out of the budget.

Beyond Golf Cars Unlimited the street took on a more genteel aspect, and monolithic churches, as big as train stations, began to appear. I was in the heart of Main now, at the doorstep of the Museum of Fine Arts. A nineteenth-century American landscape exhibit was in progress, and I went in and let myself be lulled by those big canvases with their haunted, morose colors and sharp reportage. Most of the paintings were a little corny, but I was a sucker for them, and I ached for the places, the deep mountain valleys and the churning waterfalls, that they pictured. What if Albert Bierstadt had come through Houston when the original turf still showed through? Would there have been anything to attract his eye? I believed so, and imagined the painting he would have left: an endless rolling plain, soft as a cultivated lawn, the grass and the clouds above both charged with evening light.

Past the museum, just beyond the Warwick hotel, the scenic part of Main began. The same Bob Hope who had once ridden in one of Bob Austin’s golf cars has been quoted as saying that this part of Houston—south from his Warwick suite—was the most beautiful city view in the world.

My own opinion was not so extreme, but it was a pretty place, and after ten miles of unalloyed urban landscapes I was ready for the shade of the burly oaks whose roots buckled the sidewalks along Rice University. Across Main and Fannin was Hermann Park, where the foliage was even more insistent. At the entrance to the park stood an equestrian statue of Sam Houston, his cape swept backward, his arm pointing ahead. “The whole attitude of the statue,” wrote a furrow-browed observer in the Houston Chronicle in 1925, “seems to say, ‘Lest we forget.’ ”

But if the statue actually said that to any of the Houstonians whizzing along Main Street that day, their reply would likely have been “Lest we forget what?” Even here in the green glade, among the gnarled trees, the city seemed rudely and splendidly indifferent to the past.

Only at Rice did the past hold any sway, and there the Mediterranean architecture—combined with enough Gothic strokes to give it some backbone—seemed deliberately retrograde. Entering the physics building was like entering the nave of a cathedral. The lighting was dim, and there were marble benches where the weary pilgrim could rest. The amphitheater, where I attended a session of freshman physics, was like one of those medical auditoriums in movies where students crane forward in awe as Paul Muni demonstrates the first use of an anesthetic.

The students filed in. Some of them were wearing Walkman earphones from which tinny heavy-metal sounds were audible. Quite a few wore shorts, even though it was November. One or two arrived at their desks and went to sleep.

“How are you feeling‘?” a girl in front of me asked the boy who took the seat next to her.

“Pretty good. I think I’m getting better ’cause, like, these glands used to be like really huge.”

The professor was a friendly man in his thirties whose voice was like an echo in the cavernous hall. A paper airplane soared through the ranks, and it did not faze him. His earnestness, unforced and genial, seemed to affect the students and rouse them from their torpor.

“So what can we say?” he asked as he drew a formula for adiabatic compression on the blackboard. “We can say that P minus one over P two is equal to V two over V two minus gamma. So finally we can say that T one over T two is equal to V over V one to what power? To the gamma minus what?”

The Rice campus left off at about the point where another institution, the Texas Medical Center, began on the other side of the street. It was a massive place; the buildings crowded one another for space in a way that made the thoughtful layout of the Rice campus look languid and effete. The Medical Center appeared to have erupted out of the ground like a mountain range.

I had an appointment at St. Luke’s to watch Denton Cooley perform heart surgery, and as I entered the hospital I was struck by the riotous architecture, the color-coordinated stripes in the hallways that were necessary to guide patients and visitors to the right destination. It seemed deliberately designed as a maze, and at the center of the maze was the place where the surgeon bent over the patient and touched his living heart.

On the table that afternoon lay a six-year-old boy, covered in green cloth, so that the hole in his chest looked like a rent in the fabric itself. A dozen people stood over the cavity while the boy’s blood, traveling in tubes, circumvented the heart.

Cooley walked into the operating room with his mask and cap already in place. He was wearing a pair of glasses outfitted with a special magnifying eyepiece of his own invention; its electric cord ran over the back of his head. On the seat pocket of his scrubs the word “Cooley” was written in red script.

“I went down to your reception last night,” one of the doctors told Cooley.

“That right?” he replied. “You have any of those crab legs?”

That was all the small talk. When Cooley walked over to the table and began probing through the boy’s aorta, there were only mumbles. He was looking for a hole in one of the ventricles. The heart was as shapeless as a mollusk, and it seemed to me that the surgeon’s skill was not so much in his hands but in his imaging powers, his ability to look down at that flaccid, collapsed muscle and see landmarks and points of reference.

It took Cooley perhaps twenty minutes to find the leak in the ventricle, sew it up, and then repair the incision in the aorta. As the boy’s heart was being started again I moved to the head of the table and saw his face beneath the green tarp. His eyelids were taped closed, and he looked as pallid and still as a piece of marble. In contrast, his heart was alive; it swelled up when it beat and spilled over the opening in his sternum. Cooley gently pushed it down into the cavity, and it continued to beat there, powerfully, almost sentient. It was as if the heart realized that it was linked to the boy in some fundamental way and was trying to get his attention, to rouse him.

When Cooley’s part of the operation was done he threw his surgical apron into a bin and went out, his face still hidden behind the mask and the glasses. Before I could catch up with him, he had disappeared back into the labyrinth, and so I went back out onto Main and continued walking south, headed for the Shamrock Hotel.

For me the Shamrock had always been one of the most resonant buildings in Texas. It was bought by the Hilton chain in 1954, five years after it opened, but as time went on it seemed to become even more of a monument to the man who had originally built it. Glenn McCarthy was a self-made oil field millionaire and public relations genius who was as responsible as anyone for making the wildcatter such a romantic figure in American folklore. In his prime he had tousled dark hair and a rakish moustache, was a legendary brawler, and was widely assumed to have been the model for Jett Rink in Edna Ferber’s Giant.

The Shamrock was the most outstanding example of his bravura. McCarthy decided to build not just a world-class but a real big hotel in the hitherto unknown wastes of Houston, Texas. When the Shamrock was finished it had over a thousand rooms, the world’s largest hotel swimming pool, 82 different shades of green, bellmen who dressed like diplomats, and a great hall, the Emerald Room, where celebrities clamored to perform. The official opening of the Shamrock in 1949 brought Houston to the world’s attention and helped codify the image of the Texas oilman as someone who believes class can be bought with money. The event featured every movie star that ever was. “The Shamrock Special” brought them in, and each one who stepped off the train left the native hordes more goggle-eyed than the last—Ward Bond, Macdonald Carey, Andy Devine, Kirk Douglas, Gale Storm. Dorothy Lamour presided over the dedication in the Emerald Room, which turned out to be a chaotic affair of supreme magnitude. The people who had paid $42 a plate sat in the Emerald Room, but those who had paid only $33 were shunted off to an inferior ballroom and soon degenerated into a mob, trying to force entry into the Emerald Room while hundreds of bystanders outside the hotel broke through police ranks and stormed the lobby. Dorothy Lamour left the stage in tears.

People still talk about it, and as I approached the Shamrock that day I had a little warm spot of chauvinistic pride for the place. All the rowdiness and snobbishness and shameless media-milking had faded away, and what was left was the one thing nobody ever expected: class.

Glenn McCarthy pulled up to the front door of the Shamrock in a Delta 88. It had a layer of dust on it and there were Styrofoam coffee cups littering the floor. He had just driven in the day before from his ranch in Alpine, where he retreats periodically with his two dogs, Jesse and Fluffy.

Getting out of the car, he ran a hand over the top of his head.

“That goddam weather was so cold that my damn hair got stiff on me,” he said.

At 75, Glenn McCarthy no longer looked like a brooding oil field Heathcliff, but his presence was formidable. He had a deep, growling voice and an impassive, clean-shaven face. From the front seat of his car he took a black riverboat gambler’s hat and set it at an angle on his head. Before he entered the hotel he took a watch and chain out of his pocket and examined it.

“I want to go in here and get my pocket watch cleaned,” he told me. “It’s something my wife gave me many, many years ago.”

He closed the watch, put it back in his pocket, and gave me an admonishing look.

“It’s a Patek,” he said, “and it’s real good.”

They knew him at the Shamrock. People in the lobby looked up and whispered to their neighbors. The younger members of the staff said, ”How are you. Mr. McCarthy, sir?” and the old-timers greeted him warmly.

“Every piece of wood in this whole floor came from the same tree,” he told me.

McCarthy walked through the lobby and into a corridor of shops that led to the immense swimming pool. He stopped in at Steve Chazanow, Jeweler, and handed his pocket watch to Steve Chazanow, a smooth, dapper man whose business had been located in the Shamrock since the beginning.

“Remember that watch?” McCarthy said to Chazanow.

“God almighty,” Chazanow said, turning it over in his hand. “Yes, I do.”

“I wind it, but it’s not working,” McCarthy said, ignoring Chazanow’s nostalgic reverie. “I don’t know what it is. Maybe it’s water blowing in from the Gulf of Mexico and getting in there.”

“My God, Glenn, I think this is platinum.”

“It is platinum. And those diamonds are not little chippy diamonds, either.”

Chazanow and McCarthy walked down to the dining room and took a table overlooking the vast pool. They had lunch together there about once a week.

“The Shamrock let the world know there was a Houston,” Chazanow told me, as he folded his menu.

“He’s telling you the truth,” McCarthy said. “I used to get mail that just said Glenn McCarthy, Shamrock Hotel. It didn’t even say Houston on it. There wasn’t anybody in the United States who didn’t know where the Shamrock Hotel was, and there wasn’t anybody in Europe.

I went to the George Cinq Hotel in Paris not long after we opened, and as soon as they heard my name they gave me a complimentary room. Same thing in Cairo, Egypt. Anybody that was alive then had heard of the Shamrock.”

McCarthy said he built the Shamrock out on this part of Main to decentralize downtown. He knew that Houston was going to decentralize, he had seen it happening all over the world. The question was where the city was going to grow once the lock on downtown was broken. The Shamrock, as much as anything, was what broke that lock.

“The hotel’s been a success from the day it opened,” he said. “The success of the hotel was planned. I didn’t leave anything to chance. A lot of people wondered why I would build a hotel five miles from town. But they found out.”

“Of course all the celebrities were here,” said Chazanow. “We had kings and queens. We had the Prince of Wales. What was his wife’s name, Glenn?”

“Wallie.”

“She was here. Every celebrity who was anybody played that room in there.”

“Frank Sinatra,” McCarthy said. “Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin. They all wanted to come here. I made friends with a lot of them. A lot of top actors and actresses, the greatest ventriloquists. Once we put about sixty-five hundred children in the main room three different times one Saturday. We had a ventriloquism act. Mortimer something. I forget his last name. Snerd! Mortimer Snerd. I remember the dummy, but I wish I could remember the man who did the ventriloquism part because he was a wonderful man.”

Chazanow and McCarthy reminisced about the old Shamrock for another half hour, recalling the kitchen that was a block long, the four thousand hand-cut steaks that were served daily, the legions of famous names that stayed there.

McCarthy digressed briefly about Howard Hughes (“He was a whole lot better fella than the news media gave him credit for being. He wasn’t crazy. He was a genius”) and about his own brief career as a movie producer. McCarthy’s most enduring credit was The Green Promise, starring Walter Brennan and Natalie Wood, which premiered during the opening of the Shamrock.

“It was completely against communism,” he said. “They don’t like movies like that, the communists don’t. Then I did Five Bold Women. It was about five bold women being taken to prison. I’m not much interested in movies anymore. I haven’t seen one in two years. I don’t like bebop and rock ’n’ roll and all of that horseshit.”

In the elevator corridor off the lobby of the Shamrock hung a portrait of Conrad Hilton. Glenn McCarthy’s own portrait had been there once, but it was replaced after the Hiltons bought the hotel. In 1954, when McCarthy sold the Shamrock to the Hilton chain, he made the deal with Conrad’s playboy son, Nicky, not with Conrad, whom he could not stand, but it was Hilton pere’s picture that hung there now, looking like the cat that ate the canary.

McCarthy did not glance at the painting as he walked through the lobby, but I could not help asking him if he was ever depressed at the thought that it was not really his hotel anymore.

“I don’t get depressed,” he snapped, handing a big tip to the valet who had brought his car around. “I built it, I paid cash for it, I sold it for cash, and the hotel’s still here. It’s still the best.”

I took a room in the Shamrock and just after dark looked out from the sixteenth floor, through the green floodlighting that bathed the hotel, at the distant foursquare brilliance of downtown. From it led a dark artery filled with a pointillistic glow of headlights. It was Saturday night; I called up some friends and invited them out to do Main Street.

We started at Captain Benny’s, a seafood restaurant built into a dry-docked boat that had room at any given time for perhaps sixteen or eighteen patrons, only half of whom could expect to be seated on galley stools. What I liked about Captain Benny’s, besides the seafood, which was the best in town, was the utter lack of enforced decorum. “We believe in the honor system,” said a sign at the door. “Theft of service is a crime.” This meant that each customer remembered his order and recited it to the cashier. There were no checks given, and though slipping out of the place without paying for your meal appeared to be the easiest thing in the world, you could not imagine a person depraved enough to do so. The more crowded Captain Benny’s became, the more courteously the customers behaved toward one another.

Tanked up on boiled shrimp and gumbo, we drove down South Main to the McLendon Triple Drive In Theatre, a passion pit of some renown, and parked beneath the screen where The Incubus was in progress.

“What I saw under the microscope,” John Cassavetes was saying, his upper lip twitching like a rabbit’s, “looked like sperm, but it had a reddish tinge.”

Well, it was sperm, but it was the sperm of the incubus, who was not quite human. The incubus looked like a giant slimy newt, and for reasons I never quite comprehended (having come in in the middle), he was savaging every female in town. Cassavetes, the grim coroner, was forever lifting sheets to give the audience a peak at a shredded nymphet.

We left before the next feature, another gory socket-wrencher, and drove north to the Island, a punk club up by the 59 overpass. The Meat Puppets were playing that night, and the warm-up band was the Hugh Beaumont Experience. I parked the car and we got in line behind a guy on crutches whose hair was a mass of greasy dreadlocks.

“My life sucks,” he told the cashier. “Can I get in free?”

The cashier gave him an appraising look and nodded. He charged the rest of us $5. The club was filled with teenagers, mostly, in studied costumes of defiance: chokers, chains, glinting pieces of metal sticking out everywhere. The girls were chubby, and they were heavily into the go-go slut look. The boys were invariably skinny, and they tended to stagger. One of them was not above deliberately diving into a bank of folding chairs.

Onstage was the Hugh Beaumont Experience, and they were very worked up. Their songs lasted, on the average, about 45 seconds and consisted of furious drumming-and-shrieking fits in which the lead singer shouted himself hoarse into the microphone without ever penetrating the noise. They were real dim bulbs, and even in that wasted audience there were few who could catch their frequency.

The Meat Puppets were better. They were older than the other band, and taller, and if they were not much brighter (“Uh, this is a song about going to grocery stores and places and everybody looks at you real funny”), they were at least able to stimulate the dormant boogie impulse of the wastrels before them.

Girls stood at the edge of the stage, watching studiously while out on the floor the mix-and-match dancers twitched and swayed like rooted plants.

“Vomit breath!” the crowd shouted at the Meat Puppets, who took this as a sign of encouragement. My eye fixed on their bass player, who had short blond hair that he had let grow long in front into a modified peekaboo hairstyle. When he stepped up to the microphone with his mane covering one eye and the other eye wild and dilated, he looked like a spooked horse.

We did not stay long but instead skulked out the door and over to Le Shick, which advertised totally nude girls. We walked into what in a better establishment would have been known as a foyer, where there was a doorbell. After we pushed it, a woman’s face appeared at a slot in the door and demanded $3 apiece.

We were the only customers except for an old man with an artificial larynx who, in a robot-sounding voice, invited the girls to sit in his lap. When not onstage, the dancers wore spangled underwear and flimsy tops, and they swarmed about our table relentlessly, demanding quarters for the jukebox. There was a movie of an orgy on the wall, so raw and vicious that trying to watch it was like looking into a blinding light. A radio station was playing through the sound system, and the narcoleptic couplings on the wall frequently took place to the accompaniment of an auto parts commercial or news headlines.

“Y’all wanna donate a dollar so I can dance?” one of the women said. She punched a selection in the jukebox, took off her clothes, and walked onstage and began to shimmy about a large pole that was permanently fixed in center stage. Two Houston police officers came in, shined their high-power flashlights around the back tables, and then went through a door into what I assumed was the manager’s office. Nobody seemed to mind them. The old man continued to make rumbling noises at his table, urging the dancer on. We hesitated for a while, thinking it might be rude to leave in the middle of the dance, but finally the fact of just being there became insupportably squalid.

I woke early the next morning and kept heading south. Past the Shamrock Main Street looked like the outskirts. From Holcombe to Bray’s Bayou there seemed to be nothing but steakhouses and Mexican restaurants, and beyond that the pale lid of the Astrodome was visible half a mile away. This was the beginning of an endless strip of motels and tourist courts, most of them predating the domed stadium and harking back to the time when Houstonians first became enthralled with the automobile. Prince’s and Sivil’s were here then, the great drive-in restaurants where girls from the best families competed for employment. In those days, to be a carhop in Houston was the big time. Girls wore short-skirted uniforms that made them look like usherettes or drum majorettes, and they were drilled in etiquette and diction and instructed in how to give change without touching the customer’s hand.

Fate chose one of the carhops at Sivil’s to appear on the cover of Life magazine when it ran a story about the Houston drive-in phenomenon. The girl’s name was Josephine Powell, and in that 1940 cover picture she is striding forward toward the camera across a sea of pavement, carrying a tray at eye level and wearing cowboy boots on her bare legs and fuzzy epaulets on her shoulders. Josephine Powell never really left Main Street. She is Josephine Rogers now and works as a cashier at Kaphan’s restaurant, just down the street from where Sivil’s once stood. When I walked into Kaphan’s and saw her behind the counter I recognized her from the Life cover.

“I was just out of high school when I went to work at Sivil’s,” she recalled. “My father was sick and I was the only child. I was cashiering in a theater and I made only seventeen-fifty a week. But I had a friend hopping cars making over a hundred dollars a week. I could hardly believe it.

“Mrs. Sivil advised us on everything, what makeup to wear and that kind of thing. She told the girls to be very businesslike. Then the church people banned the real short uniforms, and then they had to be no shorter than seven inches above the knee. But when we wore the short shorts business was really booming out this way. It’s kinda different now. Business is really going down out here on South Main.

“I don’t know why they picked me to be on the cover. They just came out one day and made pictures. I remember they said they were gonna pick the most photogenic, but I didn’t have any idea it would be me.”

Soon after the magazine came out, Josephine became ill with appendicitis and blood poisoning and spent the next seven weeks in the hospital and long months recuperating at home.

“It might have changed my life if I hadn’t been ill at the time,” she said. “The people at Chesterfield tobacco wanted me to be the Chesterfield girl and Goodyear wanted me to model bathing suits. But I was still too sick.”

So she went back to work as a carhop and then as a cashier at Prince’s, where she met her first husband. She lived in Dallas for eighteen months, but after they divorced she moved back to Houston and to Main Street, working for Prince’s again and then for Sivil’s.

“I came to work here at Kaphan’s twenty-two years ago and I’ve been working here ever since,” she said. “End of soap opera. Oh, and I got married again. I love Main Street. I don’t know, it’s just like home to me. I’ve considered going somewhere else to please my husband, but I know I wouldn’t like it. I’ll probably just stay at Kaphan’s until it’s time to retire, and then I can collect my social security if it doesn’t go bankrupt.”

The traffic was dense on South Main. It was a viable part of town. Tourists still came to the Astrodome and Astroworld, and patients at the Medical Center still set up residence in the hotels and the trailer parks secreted away behind every other business. There were Red Lobsters and Victoria Stations and cowboy bars. But even so it was a street that had never quite made it. Houston had decentralized, as Glenn McCarthy had predicted it would, but it had not gone much farther south than his hotel and the Astrodome, and compared to the tinted-glass elegance of the Galleria area, Main Street was just another shabby commercial strip.

And it was not much of a street on which to take a leisurely stroll. I felt conspicuous as a pedestrian, targeted. As much to get out of the traffic as anything else, I ducked into the lobby of the Grant Motel (“Some are cheaper, but none are cleaner”) and engaged the 89-year-old owner, E. H. Grant, in a conversation about the business he had run for 43 years.

“I traveled on the road for twenty-one years as a salesman,” he said. “The last three years I just got tired of it. I decided I wanted to get into something where I wouldn’t have to travel. I tried to get a Coca-Cola dealership, but that didn’t work out. Then one time I was staying in a motel in Austin. It was a beautiful white stucco building, and I just decided I’d like to have one of those.”

In his years of traveling, Grant told me, he had kept a list of everything that a traveling man might want in a motel—good lighting, preferably a bridge light between the lounge chairs to read by, a good shower head, and a good radio (amended in these latter days to a good color television).

Mr. Grant took me on a tour of his motel, and I saw it had all the facilities he mentioned. The rooms were stolid, made of brick or cinder block, and as we walked along by the pool the window units hummed soothingly. The shower heads he was so proud of were missing from the first few rooms we visited—the act of vandals—but he finally located one in what was apparently the Grant Motel’s version of the honeymoon suite—a little room with a pink makeup counter and ceramic walls.

“Here’s one,” he said, pointing to a gleaming instrument the size of both my fists. “The plumber charges thirty dollars apiece for those, but I bought ’em at twenty-three eighty-five wholesale.”

The old motelier had some work to do—unstopping a sink whose drain was clogged with pop tops and paper cups—and so I thanked him for his time and went back out onto Main Street to assume the dangerous role of pedestrian. I stopped to look at some framed prints that were leaning against a pickup truck. There were portraits of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Billie Holiday and other paintings with titles like The Watermelon Feast and Buffalo Soldiers.

“This is not a black art gallery or a white art gallery,” the proprietor told me. “It’s an art gallery. This here art is for the eye of the beholder.”

The man, whose name was Clarence Wood, told me that he did a brisk business in John Wayne and Pope John Paul II, but the heart of his enterprise was the work of black artists like Ray Batchelor and Walter Winn, for whom he had the exclusive Texas franchise.

“This is my thing,” Wood said. “After I returned from the merchant marine I had to have some means of support. See, I took to sea when I was a young kid. I’ve been to Israel, Greece, Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Rotterdam, Venezuela, Argentina, even Rijeka, Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia’s a Communist country, but during the time I was there they had this redheaded fella in charge that died recently—Tito, that was his name. Anyway, he was kind of friendly. I’m not sure if that was his natural hair or if he dyed it. He was about eighty-two years old and had no bags under his eyes at all.

“I’ve been to India, too. That’s a country of mystery. People there swallow long swords and it don’t cut ’em, they lay on a bed of nails and the nails don’t stick ’em. I believe they do have some genies in bottles down in India.”

The traffic had deepened by now. It was only the middle of the afternoon and already people were nosing their cars into position on South Main, heading out of Houston. They moved through a landscape that consisted of motels and vacant lots and strip centers. The motels were advertising free transportation to the Medical Center, day-sleeper rates, water beds, and the vacant lots were filled with little dump truck hillocks of construction debris, or they were overgrown with hardy weeds that snagged potato chip bags and Styrofoam cups. The lots were the sort of places where bodies are found, or where children come across abandoned blasting caps. I passed a medical clinic advertising VD screens and vasectomies and flu shots for $12. A banner that hung outside a freshly built apartment complex said, “Rent a lifestyle.”

I’d had my fill of roadside ephemera by the time I stopped in at the Southwestern Dog Academy. When I walked up to the door a furious, spiteful howling erupted from the bank of cages at the side of the office, and through the mesh I could see the bared fangs and the dripping saliva.

Phil Oesterman, the owner, was seated in his office below a stuffed sailfish with a crooked bill. He was dressed in a gray jump suit, and a rottweiler as big as a rhinoceros was spread out at his feet.

“We used to be called the Southwestern Police Dog Academy,” Oesterman told me, “but back about 1980 one of our dear legislators was sitting in a bar getting plastered and thinking to himself, ‘What have I done for my constituents lately? I know; nobody can use the word police in their name anymore.’ Hell, I’d been using that word since 1966. Then effective September ’81 I had to change all my signs, all my business cards, all my stationery.”

Oesterman’s business was training security dogs and selling or leasing them to clients. The clients might include a businessman who traveled and wanted a dog to protect his family or the owner of a car dealership who wanted to discourage burglars.

“I don’t have killer dogs,” Oesterman said. “I train my dogs to make you wish you were dead, but they won’t kill you. The dogs that we sell or lease to commercial accounts, those are the dogs that don’t like people. They are anti-people. One person is the handler, and everybody else is the bad guys.”

Oesterman also explained that he did not train watchdogs, which he defined as dogs that will watch someone come into your house, watch as he steals all your possessions, and then watch him leave.

I asked if I could go outside and meet some of his dogs, but he refused to introduce me, leaving me with the distinct impression that they would kill me if he did so. Stifling the phrase “killer dog,” I asked him what makes a good protection dog.

It is the individual, he said, not the breed—an individual with self-confidence and an aggressive nature.

He thought some more and threw up his hands. “What makes Larry Holmes or Sugar Ray Leonard want to get into that ring and fight?”

As I left the Southwestern Dog Academy the academicians snarled and spit at me again, and I decided then and there that I’d had enough of being vulnerable. A pedestrian in Houston is like a hermit crab without a shell. Somebody else could walk all the way to the end of Main Street if he wanted to, but I was going to drive.

I went out and rented a car and drove back to the dog academy, where Main Street merged with Alternate Highway 90. The motels and trailer parks extended this far, but the land was remarkably vacant, and it was a long way between Burger Kings. Every few hundred yards a sign announced a planned shopping mall, but the signs were faded and no ground had been broken. I passed the Vacancy Motel and the U-Stuff-It Storage Units, and in Missouri City I pulled off the road and talked to the sales representatives for Tang City Plaza, an immense Chinatown, featuring a mall and condominiums and a bank, that was scheduled to be built from scratch.

Outside of Stafford appeared billboards for housing developments: Quail Glen, Hunter’s Glen, Quail Run, Quail Green. In the center of town I lost Main Street briefly when the highway forked, but it converged again soon enough. There were long stretches when I was convinced that Main Street had imperceptibly been leached away as the highway became more dominant, but then I would see some lonely street sign in the middle of a pasture that let me know that Main was still with me.

At suppertime I pulled over at a greasy highway stop called the Viking Drive In.

“God, they make the Kilgore Rangerettes look sick!” a man was saying to his companions at the next table. “We’re talking about thirteen-and fourteen-year-old girls!”

It was just about time for Gospel Bill’s Wild West Show over at the Full Gospel Fellowship church. The church was only a few blocks away from the Viking Drive In, and by the time I got there the parking lot was nearly full.

“Hello, brother,” a woman said, shaking my hand when I walked inside.

Up on the stage was a pudgy young man dressed in chaps and vest, with a cowboy hat pushed back on his head. The audience consisted of eager, squirmy children and their parents, who seemed equally radiant with anticipation. As a signal for the program to begin, Gospel Bill fired a sixshooter into the air.

“You better sit up straight!” he yelled, and then picked up his guitar and led the audience in a series of songs and yells.

“Who’s the King of Kings and Lord of Lords?” Gospel Bill asked.

“JEE-ZUSS!”

“It’s good to be full of joy, idn’t it? We’re really gonna have a good time in God tonight!

“I want to talk about how to be free from fear. You don’t need a six-shooter to be free from fear. Fear comes at you and tries to make you afraid. It may be a thought that there’s something in your room at night, it may be a bad thought that you can’t pay your bills.”

Gospel Bill picked up a machete. “The Bible says in Hebrews chapter four verse twelve that the Word of God is sharper than a sword. Now here in my hands I have a machete. These machetes are sharp. These things’ll chop right through a good-sized tree. Well, the Bible says that God’s Word is sharper than a machete. God’s Word is an invisible sword. It comes outta your mouth when you speak the Scriptures.

“You say to that devil, ‘Mr. Devil, the Lord hasn’t given me the spirit of fear.’ ”

Gospel Bill threw an apple into the air and neatly divided it with the machete.

“You cut that temptation right half in two! Satan comes along and puts the sickness on you. Did you know that cancer is just the same in God’s eyes as a runny nose? I tell ya, you cut the devil’s power right half in two when you use the Word of God!”

Gospel Bill and his partner, Nicodemus, a Gabby Hayes type, put on a puppet show about a little boy who conquered fear by reciting a verse from Second Timothy whenever a knob-headed devilish puppet appeared and told him there were snakes under his bed. After that a man in a dog costume came out. This was Faith Dog, who recounted how when he was a puppy he was backed up in the corner of the yard by a skunk, who had his tail raised, ready to spray. Fortunately Faith Dog had the presence of mind to remember that the only thing that would get him out of such a jam was a good Scripture.

“Faith Dog,” Gospel Bill said, “that sure was a good testimony. Boy, I’ll tell you what, that dog’s always speakin’ and barkin’ Scripture!”

According to the Houston police dispatcher and a puzzled functionary at Stafford City Hall who had never had the question posed to him before, Main Street ended at the city limits sign at the far side of Stafford, just a half-mile or so from Al’s Barbecue (“As Tender as a Woman’s Heart”).

Just before the city limits sign there was an intersection with four gas stations and a strip shopping center whose parking lot melded into a persimmon grove and a falling-down barn.

This far south, Main Street had a very faint pulse. Most of its vital signs, for me, were farther north. I recalled the rip-snorting elegance of the Shamrock Hotel, the split breastbones and exposed hearts at St. Luke’s, the overripe adolescent furor of the Meat Puppets, the lewd vulval displays of the dancers at Le Shick. All of these things, along with Gospel Bill and his Scripture-quoting dog, shared a place in the mainstream, and I thought that if I followed Main Street long enough I would find some fertile delta, a compost of all the vanished parades and unrealized dreams and strange or seemly behavior that had ever been caught in the flow. I stood in the parking lot for a while, pondering such matters, and then got into my car and slipped into the traffic. There was only one way back, and that was Main Street.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston