Jeffrey Wood and Daniel Reneau had only known each other for a couple of months when, on the morning of January 2, 1996, Wood waited in the car as his new friend entered a Texaco station in Kerrville. When Wood, a 22-year-old with no prior criminal record, heard gunshots, he went inside the store to find the attendant, Kris Keeran, shot dead. Wood says that Reneau then pointed his .22-caliber handgun at him and forced him to steal the surveillance video and drive the getaway car.

Witness reports led police to Reneau and Wood, and the pair was arrested the next day. Reneau, who confessed to the crime, was convicted of capital murder in 1997 and sentenced to death. He was executed five years later, in 2002. Wood didn’t pull the trigger, but prosecutors tried him for capital murder under the Texas Law of Parties, which holds that someone can be held liable for an offense committed by another person. A jury found Wood responsible for either intending or anticipating the murder Reneau committed and sentenced him to death. His execution is scheduled for August 24, 2016.

Both Wood’s family and his lawyer have long maintained that his trial was flawed from beginning to end. A jury first found Wood incompetent to stand trial, and he was committed to a psychiatric institution. Less than three weeks later, Wood was determined competent by a psychiatrist to stand trial. After he was convicted, he tried to represent himself during his sentencing, but the judge denied that request, effectively finding him mentally incompetent to do so.

Lucy Wilke, who prosecuted Jeffrey Wood in his 1998 trial, writes via email, “He did not pull the trigger, but he was definitely the ring-leader [of the robbery].” She confirms that Wood’s lawyers did not present any mitigating evidence and that they didn’t cross-examine state witnesses during the punishment phase of his trial. “The reason for that was because Wood specifically, on the record, instructed his two very experienced and competent attorneys not to present any evidence or cross-examine any State witnesses,” Wilke writes.

“Unfortunately, even though the judge found him incompetent to represent himself, nobody stopped the proceeding to inquire as to his competency to stand trial at that point or to make these irrational decisions,” counters Jared Tyler, who took on Wood’s case in 2008. “I believe Wood was incompetent to make the decision not to defend himself. It was irrational and in line with the evidence on which a jury had previously found him incompetent to stand trial.” Tyler adds, “I’ve never seen a case like Mr. Wood’s, in which a person has been executed or will be executed in which there was no defense at all on the question of death-worthiness.”

And it is precisely this—the question of death-worthiness—that should be seriously considered in Wood’s case.

Wood has an IQ of about 80, which is below average. According to school and psychological records, he has always had trouble processing information. At home he was severely beaten with a razor strap for his poor grades, and in school he craved attention. When he was 12, a psychologist noted his hyperactivity, impulsiveness and short attention span. He also described Wood’s anxiety and tension, his poor grooming and hygiene, as well as his “exceptionally poor judgment” and his “faulty reasoning and reality testing.” In an affidavit to the state, his father wrote that Wood had problems planning for the simplest things and that “[w]hen he was small, he would take the blame and the punishment for something that another child had done so he would seem to fit in.” Wood was put in a Special Ed program and was never able to catch up with his classmates. In his early twenties, he fell in with the wrong crowd. It was easier for him to be around people with whom he didn’t have to compete intellectually. This is where Daniel Reneau, a 20-year-old homeless drifter with an extensive criminal history, came into the picture.

“Mr. Wood was very vulnerable to the influence of Reneau,” Tyler says, adding, “[Wood] is the kind of person who will just acquiesce to questions of authority. He is a boy in a man’s body. Because of his psychological and intellectual impairments, he does not understand the legal and other implications of what he says. He is also not a reliable historian. I believe Mr. Wood to be incompetent.”

Many states have laws comparable to Texas’s Law of Parties, but few apply them to the death penalty; fewer still have actually executed people who didn’t directly cause someone else’s death. Since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, only 10 individuals who didn’t directly kill the victim have been executed, one each in Florida, Utah, Oklahoma, Indiana, and Missouri, and the remaining five in Texas. What sets these cases apart from Wood’s is that most capital defendants were present during the murder, sometimes even fired shots or participated in torturing the victim.

“What you have is a statute that allows someone who is a party to be sentenced to death under what I believe is a lesser burden than being the actual triggerman,” says Tim Cole, a law professor at the University of North Texas and former district attorney of the 97th district. “I think there is a problem with that. These days, defense attorneys are put under a microscope. This kind of case would not be tried as a death penalty case in most places, probably not even here in Texas.”

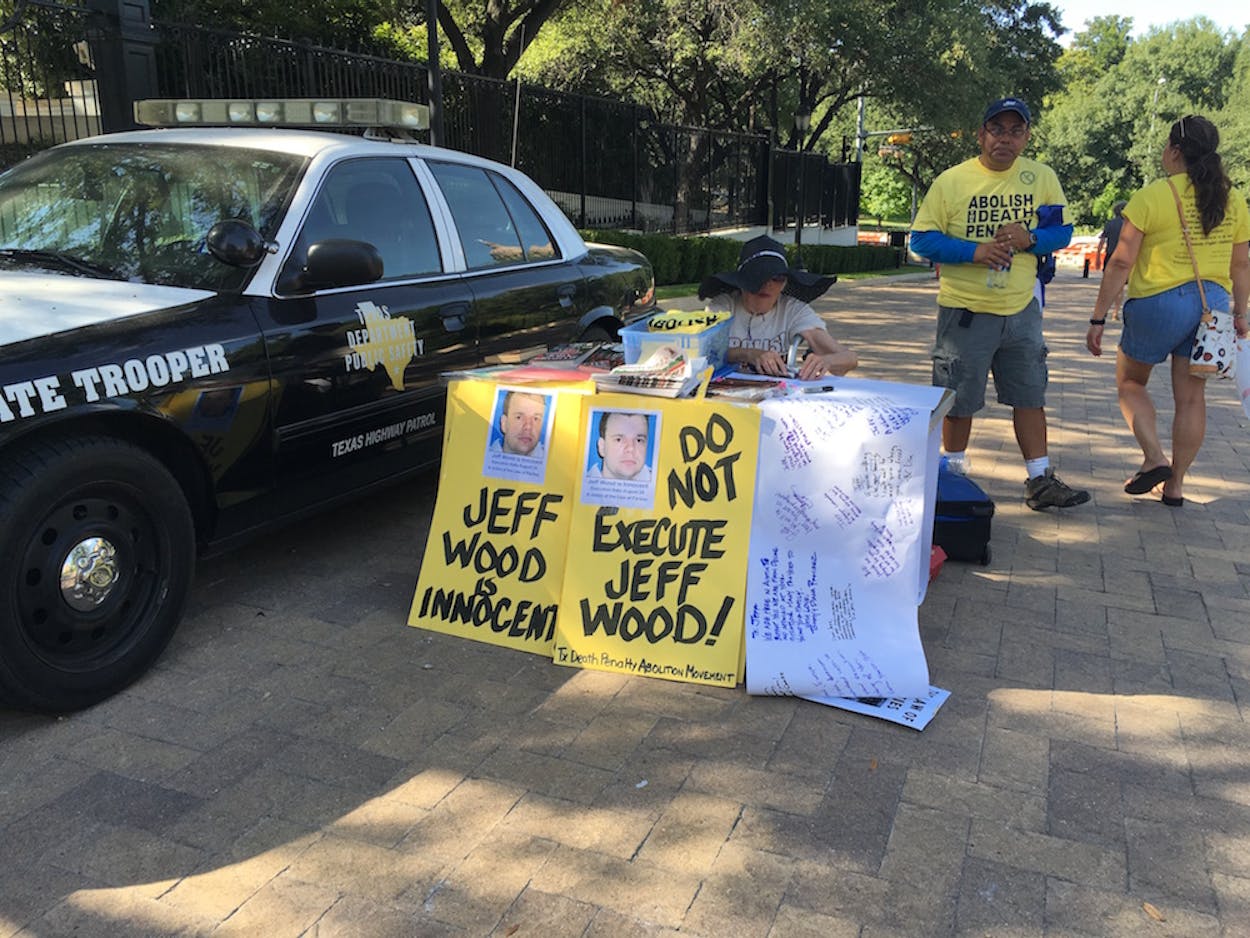

Few people know that the death penalty can be applied when someone is convicted under the Law of Parties—and among those who do, it has long been a contentious issue. In 2009, Jeffrey Wood’s sister, Terri Been, and a group of advocates from the Texas Moratorium Network came close to having a bill passed by the state Legislature that would have limited the death penalty as a sentencing option under the Law of Parties. The Texas House of Representatives approved the bill, but Rick Perry, who was governor at the time, threatened to veto it if it went through the Senate. It will be reintroduced in the next legislative session, in January 2017.

But let’s give the law as it stands now the benefit of the doubt: If Wood didn’t suffer from emotional and intellectual impairment, one could potentially argue that he should have been able to anticipate that Reneau would murder Keeran. But even then, the Supreme Court has held that the death penalty “be limited to those offenders … whose extreme culpability makes them the most deserving of execution.” The death penalty is reserved for “the worst of the worst,” according to the Supreme Court. If Wood wasn’t present for the shooting, is he equally responsible as Reneau for Keeran’s death? Is an intellectually impaired man who drove the getaway car the worst of the worst? Would a prosecutor seek the death penalty in Jeffrey Wood’s case today?

“If I had this case to make a decision on today,” wrote Wilke, who is an assistant district attorney in Kerrville, “I would make the same decision.” But had Wood been tried today, it is unlikely he would be sentenced to death. In 1999 juries sent 38 people to death row; in 2015 and 2016 combined, they condemned just five new individuals to death, none of them under the Law of Parties.

Wood’s lawyer and family are now seeking clemency, but could it be granted? Clemency is rare but not entirely unheard of. Since the death penalty was reinstated, 280 death sentences have been commuted on humanitarian grounds, often because of possible innocence, but also because some governors considered the death sentence disproportionate to the crimes the prisoners were convicted of, or because they acknowledged a “disturbing racial pattern.” (Almost 42 percent of all people on death row are black, compared to roughly 12 percent in the general population. Wood is white.)

In Texas only two death row inmates have been granted clemency since 1976. (The state has executed 537 people and counting in that time, more than any other state in America.) In 1998, Governor George W. Bush commuted alleged serial killer Henry Lucas’s sentence to life without parole, citing possible innocence. Lucas died in prison in 2001. In 2007, Rick Perry, under whose tenure 319 individuals were killed, spared the life of Kenneth Foster who, like Wood, was sentenced to death under the Law of Parties.

Since he was sworn in on January 2015, Governor Greg Abbott has not granted a single clemency. Nineteen executions have taken place during his time in office, and seven more death-row inmates are scheduled to die by the end of October.

“The commutation process in Texas has been criticized as being virtually non-existent, and that has not changed significantly from Governor Bush to Governor Perry to Governor Abbott,” says Robert Dunham, director of The Death Penalty Information Center and former capital defense attorney. Yet, Dunham says, there has been a remarkable change in public opinion on capital punishment. Today 61 percent of Americans favor the death penalty, compared to 80 percent in 1994, according to a recent Gallup poll.

In general, people are more skeptical than ever of the variables that factor into death sentences. “The single most likely fact that determines whether you face the death penalty is what county did the offense take place in and what’s the prosecutor’s view about the death penalty,” Dunham says. “When you look at the crimes committed by people who were sentenced to life and the crimes committed by people who were sentenced to death you can find very little difference between the two. There’s more and more evidence that the death sentence has been administered arbitrarily and unfairly.” Dunham adds, “And it does not make the public safer. There is no evidence that the death penalty deters.”

Wood’s chance for life now rests on the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and on Governor Abbott, who together have the power to commute his sentence. Wood’s clemency application is due by Wednesday, August 3, 2016, three weeks before his scheduled execution. The TBPP releases its recommendation to the governor 48 hours before the scheduled execution. If a majority of the board recommends clemency, the governor can grant a commutation of Wood’s sentence to life in prison or a one-time, 30-day reprieve of execution.

“Mr. Wood understands that his execution is looming but he has difficulties processing why it is happening to him,” his lawyer, Jared Tyler, says. “He doesn’t understand why the state is trying to kill him.” In the past Wood has claimed that his death sentence was tied to a conspiracy by the Freemasons. In 2008, Wood’s bizarre statements during trial and in prison prompted a federal judge to stay his last execution.

Even supporters of the death penalty, which is supposed to be reserved for the worst of the worst, should recognize the limits of relying on the flawed and arbitrary procedures of yesteryear to kill a penniless man with reduced intellectual capacities. This case is an opportunity for the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and Governor Abbot to be empathetic and morally brave, to examine past shortcomings and to save Jeffrey Wood’s life.

Sabine Heinlein is a freelance journalist and author.