While results of new food purifying technology designed by Texas Tech University may be “instant,” the “instant” success being seen by its spin-off company using microwave technology to purify food and water has actually been in the works for almost a decade.

MicroZap (MZ) is the technology company commercializing the microwave and food safety research of Texas Tech scientists Mindy Brashears, professor in food microbiology and food safety, as well as director of the International Center for Food Industry Excellence (ICFIE); Andreas Neuber, associate director of the Center for Pulsed Power and Power Electronics and AT&T Professor in the Whitacre College of Engineering; Chance Brooks, associate professor of meat science in the Department of Animal and Food Science; and Todd Brashears, associate professor in the Department of Agricultural Education and Communications.

Neuber said the MicroZap technology will heat, but not directly damage the DNA of a biological substance.

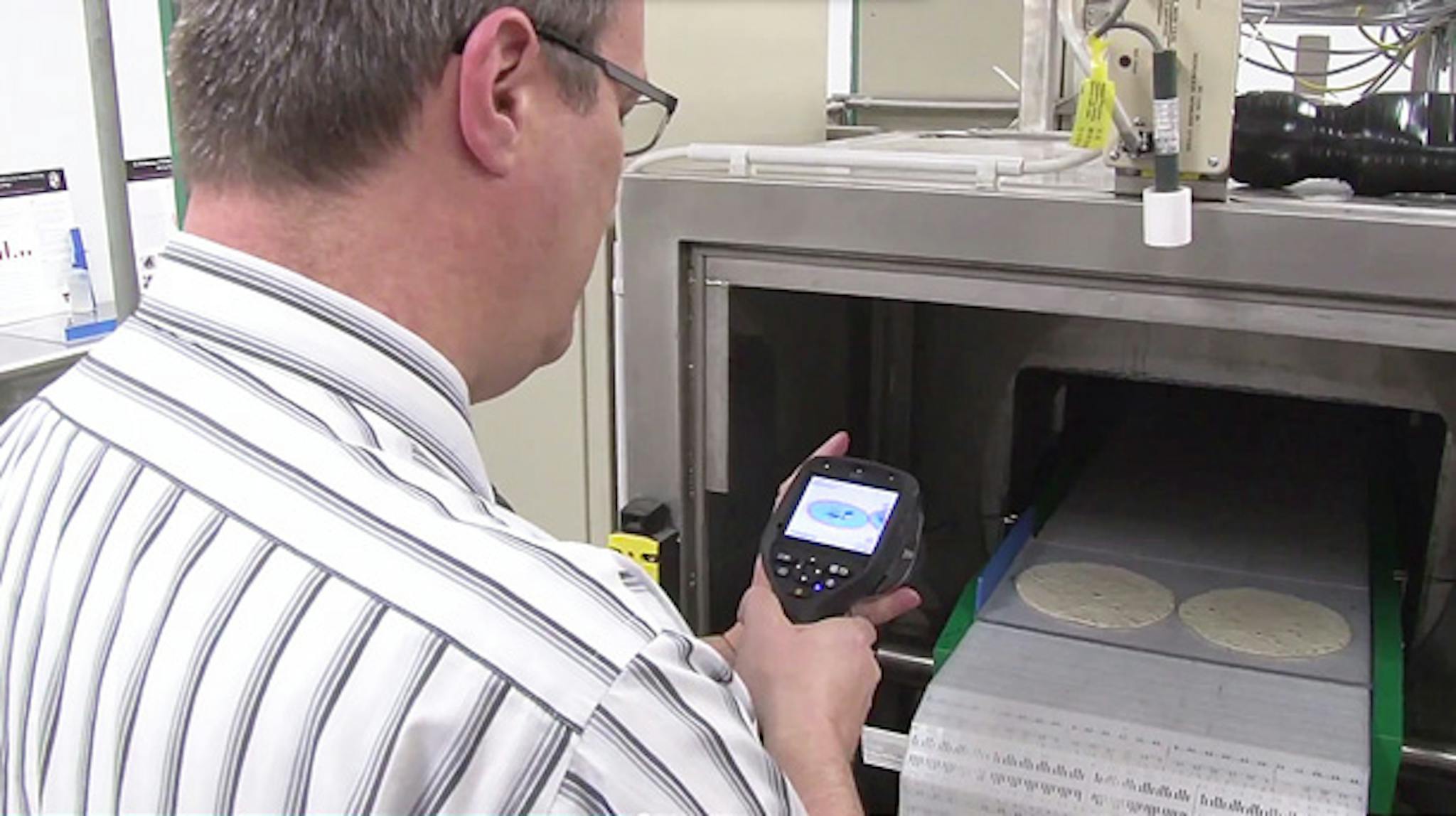

“We use electro-magnetic radiation (microwaves) which interacts with the molecules in the product or sample and will affect pathogens, bacteria and mold in the different products we treat,” Neuber said. “The unit has levels on the outside similar to those produced when people use their microwave oven in the home. MicroZap technology is very similar, except that we work with much higher fields on the inside. We have been extremely successful treating mold in bread products and have extended the shelf-life of bread to 60 days.”

Mindy Brashears said the technology for MicroZap was originally invented by a group of scientists in Italy.

“It’s been almost nine years since we’ve started this process,” Brashears said. “By the time you start having success and you start hearing about it, and it starts to hit the media, there already has been a lot of background that has gone into that technology. We’ve spent a lot of time doing research, writing manuscripts, publishing, working very hard building the company to get to this point today where we’re close to commercialization.”

The Italian scientists found Texas Tech’s ICFIE and invited the group to Italy to learn the technology. Upon doing that, there were many applications the scientists were able to come up with and many ways that they could modify the technology to make it better and take it to the next level, Brashears said.

“As we scientists started going through this process, the university realized that this could actually move ahead to a company,” she said. “They wanted us to go out and really form one – which is something that most scientists don’t really enjoy doing. But we did, and we formed an LLC, and the university helped us find investors,” Brashears said. “Through those investors we were able to come up with a business plan; we have a CEO, a board of directors, stocks and shares – a really legitimate company for this process. The technology and all the intellectual property rights were transferred from the Italian group to Texas Tech, and the patents were filed either through the university or through the company.”

In good company

Don Stull is the CEO of MicroZap, as well as a licensed professional engineer who earned his Bachelor of Science in Engineering and his MBA from Texas Tech.

“We started MicroZap in 2008 when we licensed the original technology from Texas Tech for treatment of eggs and bread,” Stull said. “Since then we have worked with Texas Tech in a very close collaboration to advance and commercialize the technology.”

The company received $1.5 million in March 2010 from the state’s Emerging Technology Fund to get the project off the ground.

Stull said they have expanded the technology to numerous other food products such as peanuts, produce, pet food, and non-food products such as mold on wine corks.

“We’ve also broadened our ability to treat other dangerous pathogens such as listeria and E. coli as well as the capability of killing the deadly superbug MRSA in homes and healthcare facilities.”

Global food security

Brashears said this technology can have a huge impact on food security, which means providing the world with a safe and abundant food supply and water supply.

“We started with whole eggs,” Brashears said. “You can take a whole egg, put it through the microwave and pasteurize it, kill the salmonella without cooking the egg and without changing the functional properties. You can still make a meringue out of it, it still looks like a fried egg if you fry it – this just shows the unique way that we target this energy to kill the bacteria.

“The technology is very good at killing molds; what a lot of people don’t realize is that there is such a huge amount of food waste,” Brashears said. “A lot of our product is thrown away – in the U.S., 40 percent of all food is thrown away.”

She said another problem with mold is it has aflatoxins which can cause cancer, and by using MicroZap technology, they’ve seen a reduction in those pathogens as well.

Brashears said many areas of the world have water that is not healthy because it has germs, bacteria, parasites, viruses and other things that make people sick. However, she said, water is the most easily treated product in the microwave because the microwaves excite the water molecules more easily than other substances.

“One of our goals at MZ is to develop a unit that is fully solar powered and put this in a developing country with central location sites that could be run by citizens of that country as a source of income,” Brashears said. “People could bring their grain – and also water – there for treatment. People could put it through the process and come out with water that’s safe and drinkable and won’t cause illness.”