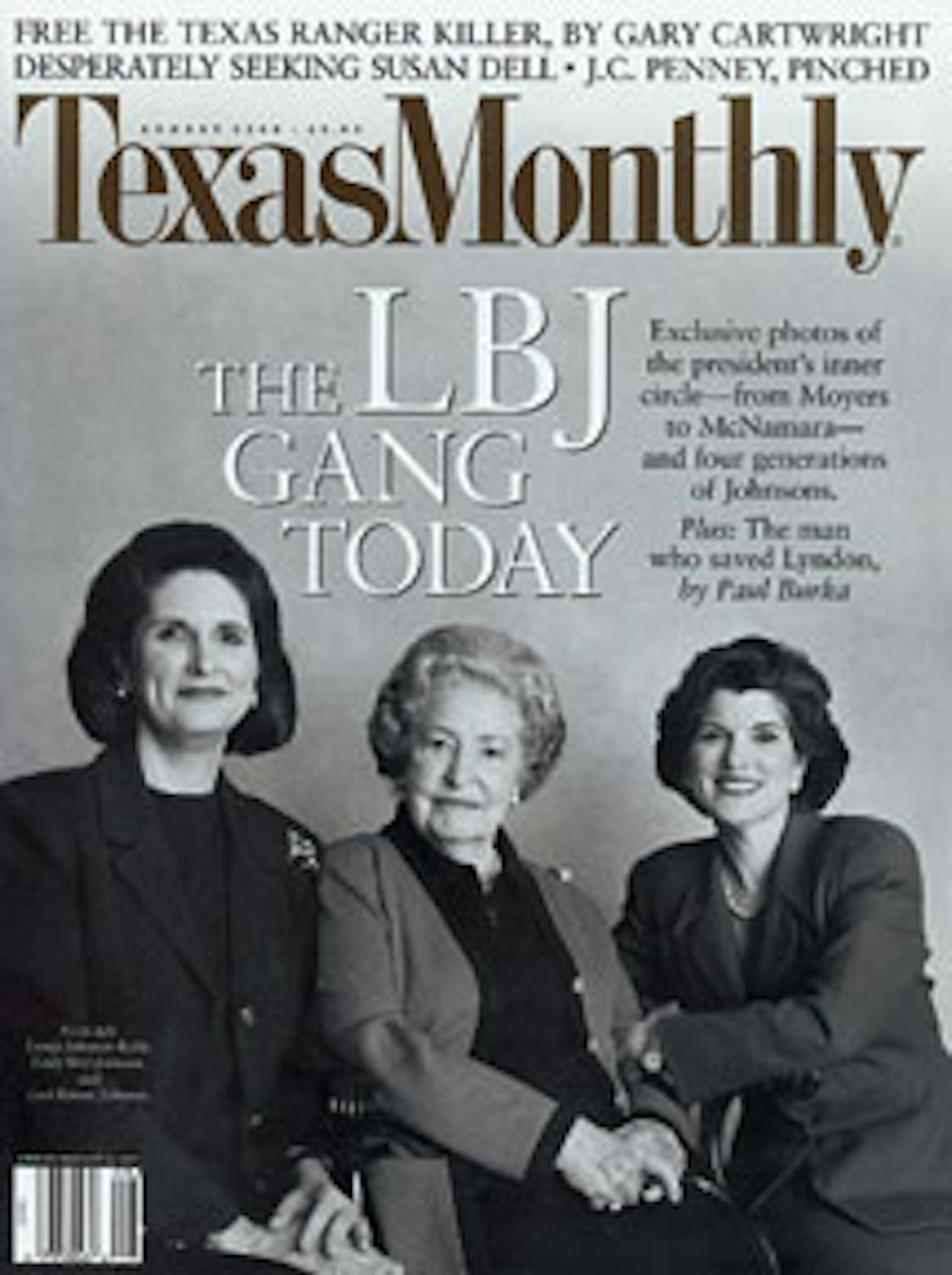

My very first issue as the editor of this magazine—August 2000—had Lady Bird Johnson on the cover, flanked by her daughters, Lynda and Luci. Back then I hadn’t yet met the matriarch of Texas’s first family; certainly she didn’t know me from Adam (or Greg). But we would become acquainted over the next few years, when she was less than her full self physically. In 2002, at age 89, she had a minor stroke that left her unable to speak for the rest of her life. Around the same time, my daughter, Carson, started kindergarten alongside John Covert, a great-grandson of the woman they all called Nini. John was suddenly part of Carson’s social circle, and invitations to birthday parties at the LBJ Ranch, in Stonewall, soon followed. Mrs. J, as I came to think of her, was there, usually in a wheelchair, sometimes in a festive hat, always eager to visit, even if she couldn’t respond. (Which was a good thing on one occasion: when my crabby son dropped the F-bomb within earshot. Chip off the old block.) As Carson and John got older, Mrs. J was so often a presence at school plays and pageants that we took it for granted she’d forever be in her front-row seat.

As often happens, the parents of children who are friends become friends themselves. Brent and Nicole Covert (she’s Luci’s eldest daughter) are smart and fun and sarcastic—worthy stewards of the family brand. Nicole’s cousin Catherine Robb (Lynda’s middle daughter), a relentlessly upbeat and energetic lawyer who used to work for the firm that handled texas monthly’s business, also became a good friend. Luci and her husband, Ian Turpin, were especially kind to us at the various charity galas we all seemed to attend, and they extended their own courtesies, asking us to their apartment to watch the 2004 election returns with Lady Bird and to dinners hosted by Lady Bird at the LBJ Library. Especially in those settings, Mrs. J’s silent presiding over a table full of type-A personalities deep in conversation about the events of the day was a sight to behold.

And a memory to treasure. Journalists are not supposed to be biased about the people they cover—not openly, anyway (wink, wink). But whatever your ideological views, I submit that it was hard not to like Mrs. J, to admire her for her sacrifice on behalf of kin and country, and to respect her for her considerable accomplishments (many of which are recounted in our cover story, “A Lady First,” by writer-at-large Jan Jarboe Russell, who was one of her biographers; see page 138). When I was around her, I felt as if I was a witness to history, as much as it may be a cliché to say so. I kept my eyes and ears open and my mouth closed, or tried to. I felt cowed, and lucky.

And I felt sad, genuinely so, when she died. It wasn’t a surprise; her health had been an issue for so long, and there were repeated trips to the hospital (and let’s remember that she was in her nineties). But her passing was more than simply the departure of a mythic figure. She modeled behavior for all of us in a way that few people in public life did before or have since. She embodied values too rarely on display: true selflessness, a commitment to service, an embrace of faith that unites rather than divides, and courage and civility in the face of its polar opposite. To hear Bill Moyers tell the tale, as he did at her funeral, of her journey through the segregated South in support of civil rights is to understand what a rare and honorable bird she was.

Next Month

Big Bend, Donald Judd, Miranda Lambert, Bill Wittliff’s Lonesome Dove photos, and Robert Draper on the making of George W. Bush.