I’d not seen my stepbrother Dale in more than two years when a bitter norther slammed into Texas in December 1989. Schools closed, pipes burst, and sleet-covered highways took on the look of salvage yards. I was sitting alone one blue-gray afternoon, listening to the frozen rain tick on the windows of my house in Belton, when the phone rang.

It was Dale’s mother, and she was in a panic. She was at Arlington Memorial Hospital, where her son was in intensive care. “He might not live through the night,” she said. “You’ll have to tell your mother and stepfather. They’ll never believe me if I call them.” I knew she was right; ever since her divorce from my stepfather, more than thirty years earlier, he had done little to hide his loathing for her, even after he’d retained custody of their two sons, Elden and Dale, and rebuilt a family with my mother and me. I promised to be at the hospital as soon as I could, then phoned my mother in Oklahoma. “What’s wrong with him?” she asked, stunned. I told her I didn’t know.

But that was not exactly true. Sitting in the car on my way to the hospital, inching across the ice on Interstate 35, I played news headlines from recent years over and over in my head. AIDS, a disease unknown to Americans just a decade earlier, was filling hospitals and clinics and hospices across the country with patients covered in lesions and fighting for each breath as their lungs were steadily destroyed. And in the late eighties, only one outcome awaited its victims: death.

The disease was not an equal-opportunity killer. True, straight men, children, women, even one nun were among the dead. The disease could take years to develop after initial infection. A blood transfusion during surgery, experimentation with injecting recreational drugs, a one-night heterosexual stand during the wild seventies—even in the early years of the pandemic, people knew that any of these could lead to AIDS. But the overwhelming number of people dying from the disease were gay men who had contracted HIV, the blood-borne virus that causes AIDS, through unprotected anal sex. Some born-again preachers and politicians proclaimed AIDS to be “the gay plague,” God’s punishment for homosexual perverts.

My family came from a small town in Oklahoma that could hardly be described as open-minded. AIDS was not a topic that my parents discussed. (In fact, I can remember no conversations concerning sex.) My education on the disease had come almost entirely from the book And the Band Played On, which I’d read the year before. I’d recognized Dale’s life in its pages. Now, thinking of him, I gripped the steering wheel, dreading what awaited me in Arlington.

I arrived at the hospital to find Dale lying unconscious in the ICU. He was connected to a ventilator, and each time it breathed for him, his body jolted. After going bald in his twenties, he’d taken to wearing a toupee, but the dark-brown, almost black bouffant was gone, and his pale head on the pillow struck me as impossibly small. His hospital gown was open, revealing crusty lesions on his chest. I reached down and took his hand. He squeezed, but it seemed like just a reflex.

I asked a nurse what was wrong. When she said she could not comment to anyone unfamiliar with Dale’s “underlying physical issue,” I lied, saying I knew all about it. She paused. “He has something that’s like pneumonia,” she said, “but not exactly pneumonia.”

“Pneumocystosis?”

“Yes,” she said.

I nodded. I knew about pneumocystosis from my reading. Caused by a fungus, it was a devastating lung infection similar to one that had been found only in rats—until, that is, gay men in San Francisco began showing up with it at hospitals in the early eighties. Only one thing could so damage an immune system that someone could contract the infection. My stepbrother, lying before me, was dying of AIDS.

I found a pay phone in the hallway and called my mother. The diagnosis was complicated, I said, and she and my stepfather needed to come to Arlington quickly.

Heading back to the ICU, I ran into my stepbrother’s business associate, Tony. We’d met just once before. He and Dale ran a dried-flower store at the massive Grand Prairie marketplace known as Traders Village, where you could seemingly buy everything from used tires to precious stones. It was there, maybe three years earlier, that Dale had given me a promotional vinyl copy of Willie Nelson’s Phases and Stages, and Tony had shaken his head, muttering, “You like Willie?” He and Dale played LPs like Carly Simon’s Torch. But Dale knew I was as much shit-kicker as aging hippie, and he’d picked up the Willie record for me from a Traders Village dealer.

“I guess you’ve figured out what’s wrong with him,” Tony said. I nodded again. “He’s so afraid his dad will find out. He’s told the doctors and the hospital staff not to discuss anything with anyone unless they know already.”

Suddenly, he reached out to embrace me. I hugged him awkwardly. His eyes began to water as he shook his head. “He just can’t have his dad find out.”

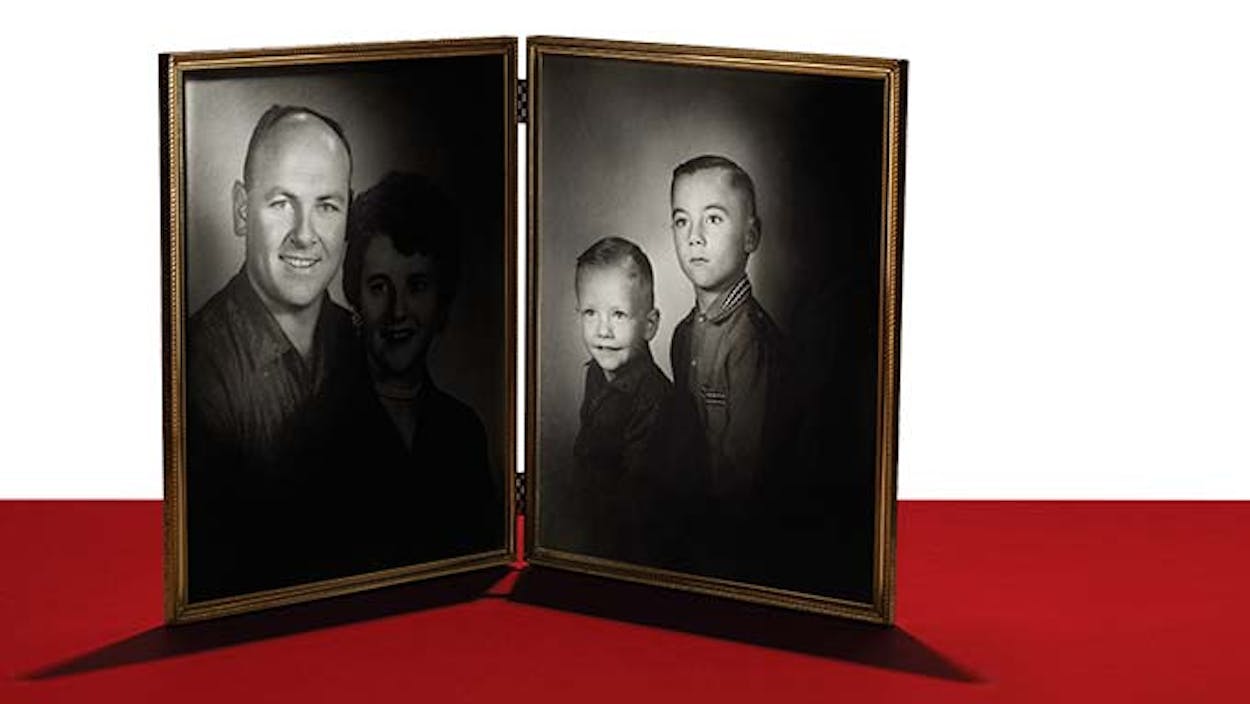

My mother married my stepfather, Ferdy Waner, a beefy mechanic who’d also worked as a roughneck, three weeks shy of my third birthday. Because my runaway “real” father was out of the picture, I called my stepfather Dad. Elden and Dale were older than me, by five and a half and four years, respectively. Elden was compact, muscular, and outgoing—ready to battle it out with anyone or anything that challenged him. Dale was tall, skinny, and pale; soft-spoken and reserved, he had a stoicism that served him well in the tough environment in which we grew up. Money was hand-to-mouth scarce. Early on, we understood the concept of making do. At home and at school, the rules laid down were strict, and discipline could literally sting. We boys were taught that life was hard, something that only rarely provided much in the way of joy.

Dad governed our world. He was an extraordinary physical and moral force. He had survived the Oklahoma dust bowl and West Texas oil booms. He was the strongest man I’ve ever known. I once saw him drag a dump truck into his shop using only his massive muscles and a chain wrapped around the truck’s bumper. My life eventually brought me into contact with professional rodeo cowboys, football players, and boxers, but none could compare with him in terms of pure toughness. His hands were as hard as a steer horn from decades of brutal work. He left his shop every day scalded, cut, and bruised, yet he accepted the pain as if it were nothing, just part of life. When he said “straighten up and fly right,” you listened.

The five of us moved into a trailer house adjacent to the old man’s auto repair shop in Guthrie, Oklahoma. We called this five-hundred-square-foot soup can home for five years. Most of that time, Dale and I shared a bed. I remember lying there with him as he did his eye exercise. He suffered from the Waner family curse of amblyopia, or lazy eye. The old man was essentially blind in one eye as a result of it. Dale was at risk of ending up the same way. To save his vision, he’d lie on his back on the bed, his good eye covered, and force his bad eye to track the movements of a ball that was suspended by fishing line above him.

For reasons simply not spoken of, the old man chose not to adopt me, so I bore the last name Stratton while everyone else, Mom included, was a Waner. This bothered Dale, who wanted everything to be consistent, normal. One day we went to get a haircut together, and the barber questioned us about our differences. Why was Dale’s hair so dark and thick while mine was so light and fine? Why were his eyes deep blue and mine greenish? I finally told him that we weren’t full brothers. That satisfied the barber but made Dale livid. Outside the barbershop, he pushed me around a little and told me to never tell that to anyone, never. He didn’t want people to think we came from a weird family.

Dale was a little like the old man that way. Dad had no patience for anything that challenged his sense of order. One evening, as the family watched television coverage of a vintage sixties anti-war protest, he became more and more agitated. “I don’t understand,” he said, as the gray, fuzzy footage showed demonstrators at a sit-in resisting the police. “Why don’t they just bring in machine guns and mow ’em all down?” The old man had flashes of playfulness to be sure, but they were the exception. My stepbrothers and I were careful of what we said, kept our voices low, sat up straight, and did what he said to do, knowing he could turn dangerous in an instant. I was scared shitless of him. My two stepbrothers were scared shitless too—but worshipped him at the same time.

Around age twelve, Dale lost interest in the rough-and-tumble activities that the boys in the neighborhood pursued, preferring to stay with his grandmother, who lived nearby, so he could help her with the greenhouse next to her home. He was obsessively neat and sartorially conscious, so that even in cutoffs, a T-shirt, and sneakers, he looked as flawless as a GQ model. In the bedroom we shared, the contents of my drawers were like tossed salad; his, by contrast, were boot-camp tidy. He practiced penmanship endlessly until his everyday handwriting became like calligraphy, impressive enough that friends would remark on it decades later.

Dale was also the only boy I knew who could shimmy. When television dance shows became popular, such as Shindig!, he glued himself to our black and white screen, watching every move the dancers made, male or female. Then he’d practice them, with the devotion other boys might have given to learning how to step in on a curve ball. When the shimmy, that old flapper dance move, was resurrected during the age of the frug and the mashed potato, Dale would gyrate his body from ankles to ears, arms held out to his sides. The old man never said anything when he witnessed Dale swaying to music, but disdain registered on his face.

Dad might have been bitter about his first marriage, but he did think it was important that Elden and Dale visit their maternal grandparents, and sometimes we’d make trips to the Fort Worth suburb of Richland Hills. Then, after their mother won visitation rights, Elden and Dale would go on their own, catching the Santa Fe Texas Chief and leaving for a couple of weeks at a time. I remember the fabulous red-and-yellow diesel engines at the train station when we dropped them off and how much I envied my stepbrothers for getting to ride the rails. But I felt confused when, a few years later, they decided to move in with their mother permanently, Elden going first, then Dale. I never knew Elden’s reasons for leaving. Dale suggested to me that in his case it was because his mother allowed him to smoke in her house, which would never have flown with the old man. (He walloped the hell out of me a few years later when he found out about my own experiments with tobacco.) I don’t think I actually said goodbye to either of them when they moved away. I felt neither happy nor sad about their leaving.

Elden returned to Guthrie as often as he could, and after graduating from Richland Hills High School, he moved back, never leaving again except for a stint in the Marines during the Vietnam War. But Dale stayed away, becoming something of a stranger. By the end of his high school years, with hair long enough to risk an ass-whipping from the hometown rednecks, it was clear he’d become a hippie. During one of his rare visits to Oklahoma, we were in the bedroom where he was unpacking when he said to me, “So I hear that you’ve started smoking grass.” It was true, and I told him so. “That’s cool,” he said. “I’ve been lighting up for a long time now. Just don’t ever let the old man find out. He’ll kill you.”

I knew Dale was right, and our shared rebellion renewed the bond between us. When he eventually enrolled at Northeastern State University, in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, I loved going to visit him. He had set up house in a well-worn trailer our family owned just a short drive from campus, near the old Cherokee community of Park Hill, outfitting it with a TV and a stereo. While Dale and I lit up, we watched Gailard Sartain’s late-night show, The Uncanny Film Festival and Camp Meeting, featuring Gary Busey, and listened to John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band’s Live Peace in Toronto 1969. My favorite album of his was Dylan’s Nashville Skyline. The trailer sat a stone’s throw from Lake Tenkiller, at the time a remote, emerald-colored reservoir surrounded by thick woods and flint outcroppings, and Dylan’s country crooning made the perfect sound track for that landscape.

Dale lasted in college for about a year, then moved to Tulsa, where he found a job with Emery Air Freight. He’d show up in Guthrie from time to time with hippie girls. I remember one with pale skin and dark hair that hung from her head like thin vines. She always seemed to wear the same bellbottoms and flip-flops, with their enormous soles. Then Dale developed a relationship with a young co-worker at Emery. They’d spend hours on the phone, and when he proposed marriage, she accepted.

I was there when he wed her at a chapel in Arlington in the summer of 1976. I wasn’t there when he gathered afterward with his best man and other buddies for a smoke behind the chapel and announced that he’d just made the biggest mistake of his life; I only heard about that later. Regardless, Dale seemed to want to create a traditional family life. He and his new wife wound up back in Tulsa in a small but neat house that had room enough for his black Lab, Jodi. The only thing their home lacked was air-conditioning.

But some part of Dale also required a life contrary to tradition, and within days, his bride discovered he was heavily into drugs—not just the weed and uppers I’d known him to use but also windowpane LSD and mescaline. It was too much for the young couple, and their marriage collapsed after only a few months. Dale, who couldn’t tell his family why things had gone awry, said the breakup had happened because she’d run away. When he attempted suicide a few weeks later, my parents told me that he was in the hospital because of bleeding ulcers. By that time I was so busy with college, I didn’t make the drive to Tulsa to visit him.

I met his next wife just once. Not long after his recovery, Dale returned to Texas and his air freight job. His new girlfriend, who wore her hair styled like my mother’s, seemed a strange choice for Dale, far removed from anything hippie and with a peculiar demeanor, but Dale willingly exchanged vows with her in 1979. The marriage lasted a year on the books; in actuality it survived a much shorter time. I later heard that it began falling apart on their wedding night. Whatever happened, Dale retreated to Tulsa for a short time. He then went back to Texas a changed man.

Meanwhile, in Guthrie, my parents’ life was undergoing substantial change. They scraped and saved and eventually were able to build their dream house. The old man expanded his business to include wrecker service. Elden worked for him after he was honorably discharged from the military. They made a good team, and I assumed Elden would take over the family business at some point. But he was unsettled after the Marines. He left the business after a few short years to become a cop. Later he would become, at various times, a heavy-equipment operator, long-haul trucker, and firefighter. I know Elden’s departure from the business at first upset the old man. Yet he and his oldest son energized each other, and they remained close, even though they sometimes engaged in screaming arguments. My stepfather and my mother ran the auto repair shop and wrecker service, occasionally hiring guys I’d gone to high school with as helpers. The hours were long and draining. Mom set many of her enthusiasms aside (oil painting, working at the local museum) to work in the cramped, dusty shop office. She often spent nights alone in the new house while the old man was off untangling multi-vehicle pileups on the interstate. She never seemed to resent it, though. She and the old man were inseparable as a couple.

I was the only one of the boys to live in that house. I graduated high school in 1974 at the top of my class and scored high on the college entrance exams. But no money was available for me to go to any of the universities I wanted to attend. I took a job as a reporter at my hometown newspaper and enrolled in classes at the state college fifteen miles down the highway. My parents allowed me to stay in the new house while I was in school, but the old man and I had little to say to each other. He couldn’t understand my interest in movies or why I majored in something as foolish as English. He sure as hell couldn’t appreciate my zest for the Pigpen-era Grateful Dead or even a long-haired Waylon Jennings. There wasn’t much for us to share. Besides, he thought I lacked strength, physical and otherwise.

I’m sure he understood even less about what was going on with Dale. As was the custom of their generation at that time and in that place, my parents hardly spoke of Dale’s failed marriages. Some things you just don’t talk about. Yet whatever misgivings he might have held, the old man seemed happy to see Dale when he visited at Thanksgiving and Christmas. After his second marriage crumbled, he always arrived alone except for his Lab. Sometimes Dale would drive a pickup he had bought and overhaul it in the old man’s shop. They enjoyed each other’s company. Elden seemed to distance himself from his brother. Dale put on a good face around the family, nodding at the litanies delivered about lazy workers, corrupt local politicians, and worthless businessmen. But when Dale and I were alone, he lampooned the small-town fashions, way of speaking, and coarse manners. And he let me know he loathed Guthrie.

Dale told me he was the happiest he’d ever been living in the Dallas–Fort Worth suburbs. After his second divorce, it was as if he’d made a calculation—a decision to let go of the life he’d been tied to, or thought he was tied to. He quit his air freight job and opened a dried-flower business, catering to Dallas and Fort Worth homeowners and designers looking to save money. He began working out at health clubs. And except for the toupee he’d started wearing, he looked better than he ever had—smiling a lot, laughing frequently. He was at ease.

But the more intimate details of his private life are a mystery to me. I can’t say if he frequented gay bars or anything like that. I know he had two relationships with men, both younger than him. The first one lasted for a year, maybe longer. Now, nearly three decades later, I can’t even remember that boyfriend’s name, let alone any details about him. Then Tony became part of his life, both as a romantic partner and a business associate. Tony looked strikingly like Dale, with matching dark-brown mustache and eyebrows. He was shorter than Dale, but thin like him. Tony was about my age. I knew he’d made his way from North Carolina to Texas, but that was about all. I wish I could say how they met, what attracted them to each other, when they realized they were in love. But I can’t. I was around Dale from time to time, a couple of times staying at his house in Arlington, yet it never occurred to me to ask about those things.

Still, we eventually addressed it in our own way. One December, after a family Christmas get-together, Dale had a plane to catch in Oklahoma City, and I offered to give him a ride to Will Rogers International Airport. As soon as we were on the road, he confessed how painful he found these visits. He talked about how difficult it was to return to the old hometown, how completely out of place he felt there, how he could no longer understand the relatives and friends he’d thought he knew. And he said something about how he feared what the old man must think about him. In the middle of our conversation, he stopped and looked over at me. “You know how I am?” he said.

After a pause, I replied, “Sure.”

And that was it: Dale’s admission that he was gay. Though we never actually discussed it beyond those six words, I hoped he knew he wouldn’t have to pretend anymore around me. But he would pretend around the rest of the family. Already, news about the disease called AIDS ravaging gay communities in the U.S. was familiar. Beyond that, just being gay was still taboo in many, maybe most, quarters. There was also the family dynamic. Some things you just don’t talk about. I knew a part of Dale was still that little boy who didn’t want anyone to know that ours was a weird family, the little boy who kept his socks and underwear so neatly arranged in his drawers. Appearances mattered.

I was the only one in the family who knew his secret.

It was Tony who told me, that first night at Arlington Memorial, when Dale had found out he’d contracted HIV. Two years earlier, in 1987, the two had applied for life insurance to secure a bank loan for their business. To get the insurance, they’d had to take physicals. Both had tested positive for the disease. The insurance policy was canceled, as was the loan. Not too long after that, Dale developed a cough that would not go away. For months, that was it—just a cough. Then, suddenly, his health went into a tailspin. He quickly lost his strength, to the point that he could not walk or stand. He and Tony gave up their house and moved to an apartment. Once, while Dale was home alone, in bed, a toilet began leaking and he could do nothing except lie helpless as water crept across the floors. Yet he refused to see a doctor.

Now, here he was, at death’s door. He was not the only one. In 1989 Texas had 6,312 confirmed cases of AIDS; nearly 4,000 Texans had already died from the disease. The American medical establishment offered no hope to the afflicted. People were so desperate for any chance of survival that they were willing to take drugs that had been smuggled in from Mexico; the drugs weren’t approved by the FDA and their effectiveness was doubtful, but it was something. Still, even an option like that was too little, too late for Dale. He remained at Arlington Memorial for another couple of weeks, until, because of his lack of health insurance, he was sent to the county hospital in Fort Worth. The hospital staff respected his order not to discuss his condition with anyone. My parents’ questions about what was wrong with him were dodged. They were left to speculate on their own. They ignored the obvious.

The frigid bluster never let up that holiday season, and my memories of that time are of driving and driving, slowly on the ice, between Belton, Arlington, Fort Worth, and Guthrie. At my folks’ house, the artificial Christmas tree stood in the corner, Dale’s gifts in a cluster behind everyone else’s. I don’t know what became of them, because Dale never had a chance to open them. He died on January 18, 1990, at the age of 38.

His funeral was in Guthrie a few days later. It fell to me to take Dale’s burial clothes to the funeral home. When I saw the mortician, an old family friend, I asked him what the death certificate said. “I’m so glad you said something,” he replied, pulling it out to show me. “Your folks were down here, and I don’t think they have a clue.”

There were the letters: HIV/AIDS. “He’ll have to sign this,” the mortician said, referring to the old man. “He’s next of kin. I don’t know how he’ll react when he sees it.”

At my parents’ house, I helped my mother prep beds for guests staying over for the funeral, including Tony, whom my parents at that point considered to be Dale’s business associate and roommate but nothing more. As she spread out a sheet still warm from the dryer, she began reciting what had become the narrative for her and the old man as to the cause of death: Dale had gone to Mexico to purchase bulk goods for his dried-flower business, and while there, he’d picked up some sort of pathogen borne by blowing sand that had settled in his lungs.

“Mom,” I said, “Dale died of AIDS.” I told her about the death certificate. She stuttered a bit and asked how he’d contracted the disease.

“Mom,” I said again, “Dale was gay.” It was eighteen hours before he was to be buried in our hometown’s red clay, and it was the first time any of us had ever talked about Dale’s sexuality. She protested that he had been married—not once but twice. I told her it made no difference.

“Don’t tell Dad,” she said after a pause. “Let me do it.”

I don’t know how exactly she told him, but I remember his sitting at the counter that separated the kitchen and the dining room, staring into nothingness and saying, “If he’d just told me, I think I could have helped him.” He’d trailed off. “If he’d just told me . . .”

I remember the awkwardness between the old man and Dale’s mother. I remember Tony, who spoke achingly to me about his love for my stepbrother, and whom I would never see again. I remember Dale’s new grave in the winter-dead cemetery.

The old man himself died this summer. His exit was not easy, concluding with miserable weeks in a nursing home. One morning he told Mom that Dale had come to see him during the night and was still standing in the corner of his room. Mom did not disavow him of that notion. In the days to come, she’d ask him if Dale had come to visit. But he never said more about it.

Over the quarter of a century that had passed since his death, Dale had not been spoken of often at family get-togethers, and certainly no one ever brought up his sexuality or how he had died. Even in private moments, I never heard the old man open up about Dale’s gayness or his AIDS death. I suspect it troubled him until his dying breath. Mom, on the other hand, began to talk to me about it eventually. She accepts that he was gay and is nonjudgmental about it. And one day a woman who had been a schoolmate of mine told Mom about her own gay son, who had been stricken with AIDS. Mom gave her a sympathetic ear, saying she knew what she was going through, she’d been there herself.

My schoolmate’s son has survived because of drug therapy that was unavailable 25 years ago. AIDS seldom makes headlines these days, though it remains a significant health issue. Today’s news is more likely to concern gay marriage, a concept that was hardly conceivable in early 1990. The military has progressed beyond “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” Politicians, entertainers, and other public figures not only are out of the closet but openly celebrate their gayness. It’s a shame Dale didn’t live to experience the changes that American society has undergone.

It’s even more unfortunate that he didn’t have a chance to make peace with his father. I thought about that the day of Dad’s funeral. As he aged, my stepfather was more accepting of things he would not have tolerated decades earlier. An openly gay son might have been too much, but maybe not. I’ll never know. We buried the old man up the hill from Dale’s grave, separated by half a mile of tombstones.

W. K. Stratton is currently working on a book about Sam Peckinpah and the making of the film The Wild Bunch. He lives in Austin.