This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When tigers attack men, they do so in a characteristic way. They come from behind, from the right side, and when they lunge it is with the intent of snapping the neck of the prey in their jaws. Most tiger victims die swiftly, their necks broken, their spinal cords compressed or severed high up on the vertebral column.

Ricardo Tovar, a 59-year-old keeper at the Houston Zoo, was killed by a tiger on May 12. The primary cause of death was a broken neck, although most of the ribs on the left side of his chest were fractured as well, and there were multiple lacerations on his face and right arm. No one witnessed the attack, and no one would ever know exactly how and why it took place, but the central nightmarish event was clear. Tovar had been standing at a steel door separating the zookeepers’ area from the naturalistic tiger display outside. Set into the door was a small viewing window—only slightly larger than an average television screen—made of wire-reinforced glass. Somehow the tiger had broken the glass, grabbed the keeper, and pulled him through the window to his death.

Fatal zoo accidents occur more frequently than most people realize. A year ago a keeper in the Fort Worth Zoo was crushed by an elephant, and in 1985 an employee of the Bronx Zoo was killed by two Siberian tigers—the same subspecies as the one that attacked Tovar—when she mistakenly entered the tiger display while the animals were still there. But there was something especially haunting about the Houston incident, something that people could not get out of their minds. It had to do with the realization of a fear built deep into our genetic code: the fear that a beast could appear out of nowhere—through a window!—and snatch us away.

The tiger’s name was Miguel. He was eleven years old—middle-aged for a tiger—and had been born at the Houston Zoo to a mother who was a wild-caught Siberian. Siberians are larger in size than any of the other subspecies, and their coats are heavier. Fewer than three hundred of them are now left in the frozen river valleys and hardwood forests of the Soviet Far East, though they were once so plentiful in the region that Cossack troops were sent in during the construction of the Trans-Baikal railway specifically to protect the workers from tiger attacks. Miguel was of mixed blood—his father was a zoo-reared Bengal—but his Siberian lineage was dominant. He was a massive 450-pound creature whose disposition had been snarly ever since he was a cub. Some of the other tigers at the zoo were as placid and affectionate as house cats, but Miguel filled his keepers with caution. Oscar Mendietta, a keeper who retired a few weeks before Tovar’s death, remembers the way Miguel would sometimes lunge at zoo personnel as they walked by his holding cage, his claws unsheathed and protruding through the steel mesh. “He had,” Mendietta says, “an intent to kill.”

Tovar was well aware of Miguel’s temperament. He had been working with big cats in the Houston Zoo since 1982, and his fellow keepers regarded him as a cautious and responsible man. Like many old-time zookeepers, he was a civil servant with no formal training in zoology, but he had worked around captive animals most of his life (before coming to Houston, he had been a keeper at the San Antonio Zoo) and had gained a good deal of practical knowledge about their behavior. No one regarded Miguel’s aggressiveness as aberrant. Tovar and the other keepers well understood the fact that tigers were supposed to be dangerous.

In 1987 the tigers and other cats had been moved from their outdated display cages to brand-new facilities with outdoor exhibit areas built to mimic the animals’ natural environments. The Siberian tiger exhibit—in a structure known as the Phase II building—comprised about a quarter of an acre. It was a wide rectangular space decorated with shrubs and trees, a few fake boulders, and a water-filled moat. The exhibit’s backdrop was a depiction—in plaster and cement—of a high rock wall seamed with stress fractures.

Built into the wall, out of public view, was a long corridor lined with the cats’ holding cages, where the tigers were fed and confined while the keepers went out into the display to shovel excrement and hose down the area. Miguel and the other male Siberian, Rambo, each had a holding cage, and they alternated in the use of the outdoor habitat, since two male tigers occupying the same space guaranteed monumental discord. Next to Rambo’s cage was a narrow alcove through which the keepers went back and forth from the corridor into the display. The alcove was guarded by two doors. The one with the viewing window led outside. Another door, made of steel mesh, closed off the interior corridor.

May 12 was a Thursday. Tovar came to work at about six-thirty in the morning, and at that hour he was alone. Rambo was secure in his holding cage and Miguel was outside—it had been his turn that night to have the run of the display.

Thursdays and Sundays were “fast” days. Normally the tigers were fed a daily ration of ten to fifteen pounds of ground fetal calf, but twice a week their food was withheld in order to keep them from growing obese in confinement. The animals knew which days were fast days, and on those mornings they were sometimes balky about coming inside, since no food was being offered. Nevertheless, the tigers had to be secured in their holding cages while the keepers went outside to clean the display. On this morning, Tovar had apparently gone to the viewing window to check the whereabouts of Miguel when the tiger did not come inside, even though the keepers usually made a point of not entering the alcove until they were certain that both animals were locked up in their holding cages. The viewing window was so small and the habitat itself so panoramic that the chances of spotting the tiger from the window were slim. Several of the keepers had wondered why there was a window there at all, since it was almost useless as an observation post and since one would never go through the door in the first place without being certain that the tigers were in their cages.

But that was where Tovar had been, standing at a steel door with a panel of reinforced glass, when the tiger attacked. John Gilbert, the senior zookeeper who supervised the cat section, stopped in at the Phase II building a little after seven-thirty, planning to discuss with Tovar the scheduled sedation of a lion. He had just entered the corridor when he saw broken glass on the floor outside the steel mesh door that led to the alcove. The door was unlocked—it had been opened by Tovar when he entered the alcove to look out the window. Looking through the mesh, Gilbert saw the shards of glass hanging from the window frame and Tovar’s cap, watch, and a single rubber boot lying on the floor. Knowing something dreadful had happened, he called Tovar’s name, then pushed on the door and cautiously started to enter the alcove. He was only a few paces away from the broken window when the tiger’s head suddenly appeared there, filling its jagged frame. His heart pounding, Gilbert backed off, slammed and locked the mesh door behind him and radioed for help.

Tom Dieckow, a wiry, white-bearded Marine veteran of the Korean War, was the zoo’s exhibits curator. He was also in charge of its shooting team, a seldom-convened body whose task was to kill, if necessary, any escaped zoo animal that posed an immediate threat to the public. Dieckow was in his office in the service complex building when he heard Gilbert’s emergency call. He grabbed a 12-gauge shotgun, commandeered an electrician’s pickup truck, and arrived at the tiger exhibit two minutes later. He went around to the front of the habitat and saw Miguel standing there, calm and unconcerned, with Tovar’s motionless body lying facedown fifteen feet away. Dieckow did not shoot. It was his clear impression that the keeper was dead, that the harm was already done. By that time the zoo’s response team had gathered outside the exhibit. Miguel stared at the onlookers and then picked up Tovar’s head in his jaws and started to drag him off.

“I think probably what crossed that cat’s mind at that point,” Dieckow speculated later, “is ‘look at all those scavengers across there that are after my prey. I’m gonna move it.’ He was just being a tiger.”

Dieckow raised his shotgun again, this time with the intention of shooting Miguel, but because of all the brush and ersatz boulders in the habitat, he could not get a clear shot. He fired into the water instead, causing the startled tiger to drop the keeper, and then fired twice more as another zoo worker discharged a fire extinguisher from the top of the rock wall. The commotion worked, and Miguel retreated into his holding cage.

The Houston Zoo opened a half-hour late that day. Miguel and all the other big cats were kept inside until zoo officials could determine if it was safe—both for the cats and for the public—to exhibit them again. For a few days the zoo switchboard was jammed with calls from people wanting to express their opinion on whether the tiger should live or die. But for the people at the zoo that issue had never been in doubt.

“It’s automatic with us,” John Werler, the zoo director, told me when I visited his office a week after the incident. “To what end would we destroy the tiger? If we followed this argument to its logical conclusion, we’d have to destroy every dangerous animal in the zoo collection.”

Werler was a reflective, kindly looking man who was obviously weighed down by a load of unpleasant concerns. There was the overall question of zoo safety, the specter of lawsuits, and most recently the public anger of a number of zoo staffers who blamed Tovar’s death on the budget cuts, staffing shortages, and bureaucratic indifference that forced keepers to work alone in potentially dangerous environments. But the dominant mood of the zoo, the day I was there, appeared to be one of simple sadness and shock.

“What a terrible loss,” read a sympathy card from the staff of the Fort Worth Zoo that was displayed on a coffee table. “May you gain strength and support to get you through this awful time.”

The details of the attack were still hazy, and still eerie to think about. Unquestionably, the glass door panel had not been strong enough, but exactly how Miguel had broken it, how he had killed Tovar—and why—remained the subjects of numb speculation. One point was beyond dispute: a tiger is a predator, its mission on earth is to kill, and in doing so it often displays awesome strength and dexterity.

An Indian researcher, using live deer and buffalo calves as bait, found that the elapsed time between a tiger’s secure grip on the animal’s neck and the prey’s subsequent death was anywhere from 35 to 90 seconds. In other circumstances the cat will not choose to be so swift. Sometimes a tiger will kill an elephant calf by snapping its trunk and waiting for it to bleed to death, and it is capable of dragging the carcass in its jaws for miles. (A full-grown tiger possesses the traction power of thirty men.) When a mother tiger is teaching her cubs to hunt, she might move in on a calf, cripple it with a powerful bite to its rear leg, and stand back and let the cubs practice on the helpless animal.

Tigers have four long canine teeth—fangs. The two in the upper jaw are tapered along the sides to a shearing edge. Fourteen of the teeth are molars, for chewing meat and grinding bone. Like other members of the cat family, tigers have keen, night-seeing eyes, and their hearing is so acute that Indonesian hunters—convinced that a tiger could hear the wind whistling through a man’s nose hairs—always kept their nostrils carefully barbered. The pads on the bottom of a tiger’s paws are surprisingly sensitive, easily blistered or cut on hot, prickly terrain. But the claws within, five on each front paw and four in the hind paws, are protected like knives in an upholstered box.

They are not idle predators; when they kill, they kill to eat. Even a well-fed tiger in a zoo keeps his vestigial repertoire of hunting behaviors intact. (Captive breeding programs, in fact, make a point of selecting in favor of aggressive predatory behavior, since the ultimate hope of these programs is to bolster the dangerously low stock of free-living tigers.) In the zoo, tigers will stalk birds that land in their habitats, and they grow more alert than most people would care to realize when children pass before their gaze. Though stories of man-eating tigers have been extravagantly embellished over the centuries, the existence of such creatures is not legendary. In the Sunderbans, the vast delta region that spans the border of India and Bangladesh, more than four hundred people have been killed by tigers in the last decade. So many fishermen and honey collectors have been carried off that a few years ago officials at the Sunderbans tiger preserve began stationing electrified dummies around the park to encourage the tigers to seek other prey. One percent of all tigers, according to a German biologist who studied them in the Sunderbans, are “dedicated” man-eaters: When they go out hunting, they’re after people. Up to a third of all tigers will kill and eat a human if they come across one, though they don’t make a special effort to do so.

It is not likely that Miguel attacked Ricardo Tovar out of hunger. Except for the killing wounds inflicted by the tiger, the keeper’s body was undisturbed. Perhaps something about Tovar’s movements on the other side of the window intrigued the cat enough to make him spring, a powerful lunge that sent him crashing through the glass. Most likely the tiger was surprised, and frightened, and reacted instinctively. There is no evidence that he came all the way through the window. Probably he just grabbed Tovar by the chest with one paw, crushed him against the steel door, and with unthinkable strength pulled him through the window and killed him outside.

John Gilbert, the senior keeper who had been the first on the scene that morning, took me inside the Phase II building to show me where the attack had taken place. Gilbert was a sandy-haired man in his thirties, still shaken and subdued by what he had seen. His recitation of the events was as formal and precise as that of a witness at an inquest.

“When I got to this point,” Gilbert said as we passed through the security doors that led to the keepers’ corridor, “I saw the broken glass on the floor. I immediately yelled Mr. Tovar’s name. . . .”

The alcove in which Tovar had been standing was much smaller than I had pictured it, and seeing it firsthand made one thing readily apparent: it was a trap. Its yellow cinder-block walls were no more than four feet apart. The ceiling was made of steel mesh and a door of the same material guarded the exit to the corridor. The space was so confined it was not difficult to imagine —it was impossible not to imagine—how the tiger had been able to catch Tovar by surprise with a deadly swipe from his paw.

And there was the window. Covered with a steel plate now, its meager dimensions were still visible. The idea of being hauled through that tiny space by a tiger had an almost supernatural resonance—as if the window were a portal through which mankind’s most primeval terrors were allowed to pass unobstructed.

Gilbert led me down the corridor. We passed the holding cage of Rambo, who hung his head low and let out a grumbling basso roar so deep it sounded like a tremor in the earth. Then we were standing in front of Miguel.

“Here he is,” Gilbert said, looking at the animal with an expression on his face that betrayed a sad welter of emotions. “He’s quite passive right now.”

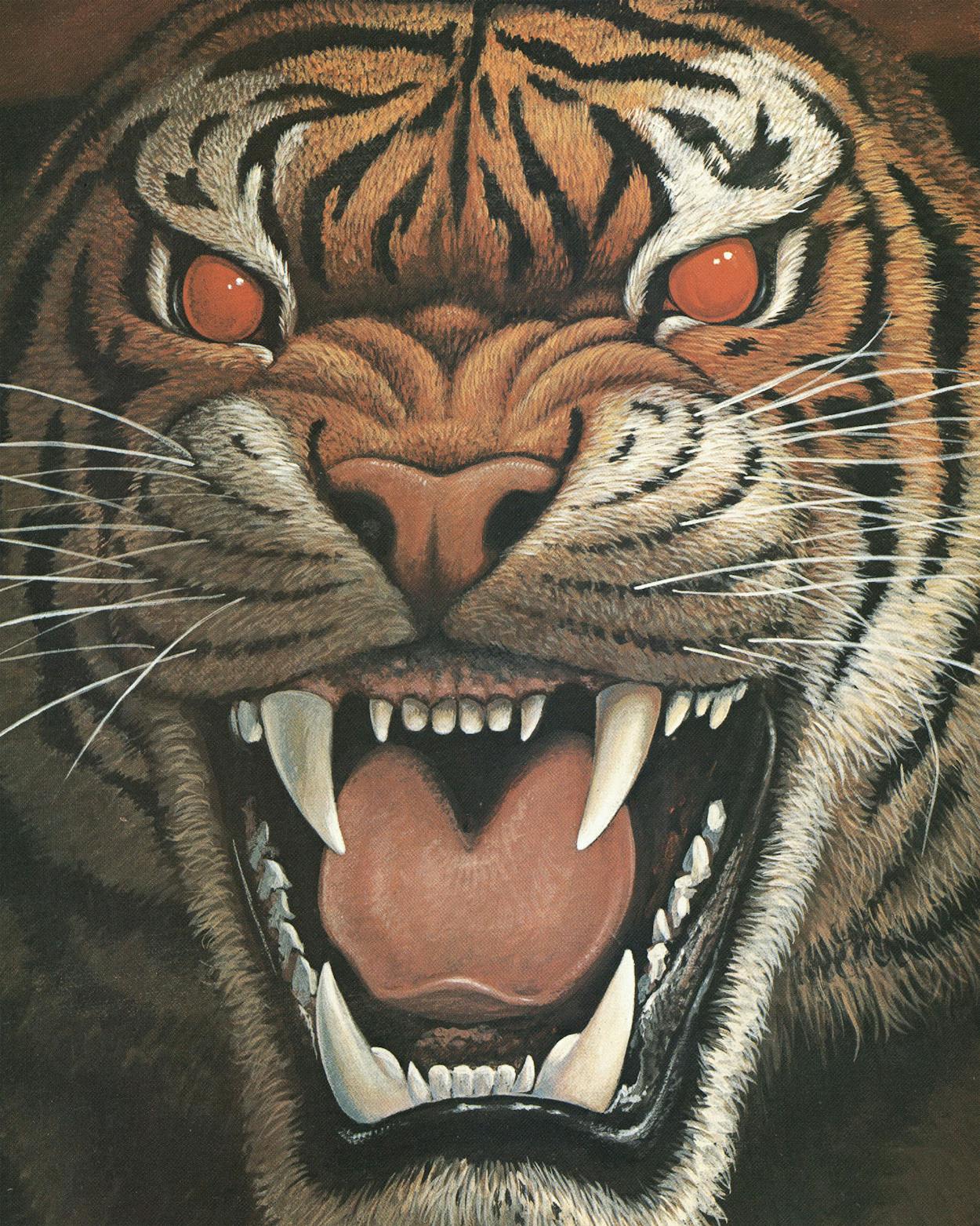

The tiger was reclining on the floor, looking at us without concern. I noticed his head, which seemed to me wider than the window he had broken out. His eyes were yellow, and when the great head pivoted in my direction and Miguel’s eyes met mine I looked away reflexively, afraid of their hypnotic gravity. The tiger stood up and began to pace, his gigantic pads treading noiselessly on the concrete. The bramble of black stripes that decorated his head was as neatly symmetrical as a Rorschach inkblot, and his orange fur—conceived by evolution as camouflage—was a florid, provocative presence in the featureless confines of the cage.

Miguel idly pawed the steel guillotine door that covered the entrance to his cage, and then all of a sudden he reared on his hind legs. I jumped back a little, startled and dwarfed. The top of Miguel’s head nestled against the ceiling mesh of his cage, his paws were spread to either side. In one silent moment, his size and scale seemed to have increased exponentially. He looked down at Gilbert and me. In Miguel’s mind, I suspected, his keeper’s death was merely a vignette, a mostly forgotten moment of fright and commotion that had intruded one day upon the tiger’s torpid existence in the zoo. But it was hard not to look up at that immense animal and read his posture as a deliberate demonstration of the power he possessed.

I thought of Tipu Sultan, the eighteenth-century Indian mogul who was obsessed with the tiger and used its likeness as his constant emblem. Tipu Sultan’s imperial banner had borne the words “The Tiger Is God.” Looking up into Miguel’s yellow eyes I felt the strange appropriateness of those words. The tiger was majestic and unknowable, a beast of such seeming invulnerability that it was possible to believe that he alone had called the world into being, and that a given life could end at his whim. The truth, of course, was far more literal. Miguel was a remnant member of a species never far from the brink of extinction, and his motivation for killing Ricardo Tovar probably did not extend beyond a behavioral quirk. He had a predator’s indifference to tragedy; he had killed without culpability. It was a gruesome and unhappy incident, but as far as Miguel was concerned most of the people at the zoo had reached the same conclusion: he was just being a tiger.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Animals

- Houston