The day after the Arabs and Israelis started their October 1973 war, C.W. “Chuck” Alcorn, Jr., drove through the heart of Central Texas hoping for an oil well. Things did not look especially promising. The sky was gray and dreary. The gently rolling cattle ranches and peanut farms of Lee County appeared barren and unyielding. But Alcorn still harbored a cautious optimism. That morning his tool pusher had called to tell him that the Halliburton crew was pumping acid down the throat of the No.1 City of Giddings. By late afternoon the job would be complete. Alcorn wanted to be on hand to see what happened next — if anything.

At first glance Chuck Alcorn looked like a Hollywood version of the vanishing Texas wildcatter. A lanky six feet four inches tall and forty years old, he had prematurely gray hair and a handsome boyish face. He was third-generation Texas oil patch, the son of an independent drilling contractor. Alcorn had paid for his college education by roughnecking in the oil fields during the summer and had graduated from the University of Texas with a degree in geology, which he had put to practical use ever since. Earlier in the day he had doffed his pin-striped business suit and changed into his oil field clothes: a khaki shirt, khaki pants, muddy brown cowboy boots, and a battered brown cowboy hat with a narrow, curled-up brim. Crammed in behind the wheel of his four-door Ford, he personified the quixotic spirit of all great Texas oil finders.

Of course, as Chuck Alcorn would cheerfully admit, he was not a true wildcatter. He had made his career in what he called “the unromantic side of the oil business.” Having begun with Gulf Oil, he was now the owner of an oil well salvage company based in Victoria. Rather than exploring for new fields, he specialized in buying up old wells and rejuvenating them with special stimulation treatments like acidizing. He was, in essence, the oil business equivalent of a used-car dealer.

Alcorn liked his work even though these were tough times for Texas oilmen. The world was glutted with foreign oil. Prices were under $4 a barrel. Drilling activity was at a twenty-year low. The major companies were selling many of their old onshore properties in order to put more money offshore or into investments other than oil, and independent operators appeared to be a dying breed. Alcorn was glad of any business he could get.

He regarded the No. 1 City of Giddings as a routine salvage job. One of only four marginally productive wells in the southern two thirds of the country, the No. 1 City had been drilled back in 1960 by Union Producing Company, which later became a part of Pennzoil. As Alcorn had the story, the No. 1 City was intended to test a potential oil-bearing layer called the Austin chalk. At first, the well had looked pretty good. It came in flowing at a rate of slightly less than one hundred barrels of oil per day and making what appeared to be a fair amount of natural gas. What was more, Alcorn was told, the oil from the No. 1 City was not the same color and consistency as the oil from its sister well, the nearby Preuss No. 1, or from the Jenke, the other productive well in the county at the time. Instead of being black and full of tar, it was an unusual light yellow, the color of honey.

Unfortunately, Union Producing had killed the flow of the No. 1 City in order to remove the drilling rig and install the proper production equipment. This was done in the usual manner: by plugging the hole with several thousand gallons of drilling mud. When it came time to start production, the mud pack was repunctured, but the flow never resumed its original rate. Instead of producing almost a hundred barrels per day, the No. 1 City coughted up only five or ten, and getting even that much out eventually required the installation of a pump jack.

Union Producing ultimately blamed the behavior of the No. 1 City on the tricky, frustrating, and often cursed Austin chalk. A stratum of fractured limestone running from Mexico through Texas and on to Florida, the Austin chalk got its name because it out cropped near the city of Austin. The part of it that interested oilmen was a band about ten to twenty miles wide and anywhere from 200 to 800 feet thick that was located at depths of 8000 to 12,000 feet. The Austin chalk was only slightly porous, which meant that it was not, technically, an oil-bearing sand. What oil the chalk contained appeared to be trapped in systems of faults and fractured in the rock. Oilmen had drilled the chalk as far back as the thirties, when the first so-called Austin chalk oil boom began, and as recently as the early seventies, when a chalk boom got started in South Texas. But chalk wells all seemed to have one bad thing in common: they came in like barnburners and rapidly gave out. A chalk boom always turned into a bust. No one really knew why Austin chalk wells acted this way, but the obvious answer was that the Austin chalk did not contain very much oil.

When Chuck Alcorn had gone round to Union Producing in 1972 looking to buy some old production, the Union men had offered him what they called “two old chalk dogs” — the Preuss No. 1 and the No. 1 City of Giddings. Alcorn bought the two wells for about $27,500, which was more or less the salvage value of the production equipment in place. His plan was to shock them back into better production by pumping 10,000 gallons of hydrochloric acid down their holes. The acid, he hoped, would clean out some of the rock crevices and allow more oil to come up, although he did no expect much from either well. He would be satisfied if he could increase their production by even twenty or thirty barrels a day.

Chalking One Up

When Alcorn reached Giddings the four-sided clock tower of the red brick Lee County Courthouse showed half past three. As usual, not much was going on in this “city” of 2500 folk, mostly German Lutherans. There were maybe three or four cars waiting at the stoplight where U.S. 290 crossed U.S. 77. There were few old pickups parked by the feed store, the two little banks, and the City Meat Market, and one or two people were on the street. That was about it.

Alcorn headed south on U.S. 77 toward La Grange, then veered off on FM 448 toward the old Giddings Airport property. Just past the city limits he turned onto a gravel ranch road. After two more left turns he pulled up at the well.

To an experienced oilman, the No. 1 City of Giddings made an odd sight. The old silver-painted Union Producing Company pump jack was still in place, but its head had been sheered off and now lay in a clump of weeks like a fallen war-horse. Alcorn’s bright-red trailer-borne workover rig was parked at a tight angle to the decapitated pump jack. Near the rig were a Halliburton “Big Red” pumping unit truck and a “Big Red” acid transport trailer. That was the standard assemble for a light acid job like this one. The thing that looked strange was the hookup at the wellhead. Instead of being just a few feet off the drilling platform floor, the nipple valve was sticking up in the air about ten feet. The flexible steel acid hose curled out of it like the stem of a hookah.

As Alcorn got out of his car he heard an unexpected racket — the sound of clanging metal. His eyes swept across the well site. The ground-level flow lines connecting the well to the storage tanks were shaking violently. The cylindrical separator unit was rocking back and forth and flaring gas. Whatever was going through the lines was moving with powerful force.

Alfred Baros, the tool pusher, rushed over from the rig. “You’re not gonna believe it,” he told Alcorn, “but it’s flowing with fifteen hundred pounds.”

The two men hurried over to the derrick. Alcorn climbed up the rig so he could read the pressure gauge at the top of the jury-rigged nipple valve. Just a Baros had reported, the gauge showed that the well was flowing with 1500 pounds per square inch, an extraordinary pressure. Unlike the scenes of oil wells in the movies, there was no great plume of oil shooting through the top of the crown block. Instead, the oil was racing through the acid hose and the flow lines, causing the loud clanging.

In order to get a look at what was coming up from the hold, Alcorn opened a needle valve near the pressure gauge. He got his second big surprise of the day. The stream that burst forth was not the sticky black he expected. It was light and yellowish. Alcorn could hardly believe his eyes. He stuck his hand in the middle of the spray and bathed his fingers in the oil.

“It’s that honey-colored oil,” he said in amazement as the memory of Union Producing Company’s experience with the well flashed through his mind. “It’s flowing that honey-colored oil.”

Now Alcorn was really getting excited. The fact that the oil flowing from the No. 1 City was a different color from the oil produced by the other wells in the area suggested that he might have stumbled onto a whole new field. The honey-colored oil also appeared to be less viscous and of higher gravity than the black oil from the other wells, which meant it would be easier to refine—and therefore more valuable—than ordinary “black gold.” It was almost good enough to pump right into his Ford and drive away on.

Alcorn got down from the rig and went over to check the storage tanks. To his further amazement, he discovered that the well had already made forty barrels of oil that day and was continuing to flow at a rate of more than three hundred barrels a day. Suddenly his old chalk dog salvage job was looking like a hell of a well.

Then Baros told his boss the bad news. Because the well had come in so fast, so strong, and so unexpectedly, the crew had not had time to remove the acid hose and install the proper production equipment.

“It looks like we’ll have to kill the well to get the equipment on,” Baros said.

“You’ll have to kill me first,” Alcorn said.

Having studied Union Producing’s failure with the No. 1 City of Giddings, Alcorn knew he did not want to repeat past mistakes. He believed that by killing the flow in 1960 Union Producing had ruined its oil well. That conclusion was based partly on some obscure technical reasoning but also on a large measure of superstition. The wildcatters who tackled the treacherous Austin chalk had an old saying: “Never kill an Austin chalk well, ’cause it’ll never come back.”

Alcorn told Baros to leave everything the way it was. He realized that the valve and hose connection was not right for producing oil. It was probably even unsafe if left in place too long. The hose could come loose and then there would be oil spraying everywhere, making a gusher that would put the movies to shame. But that was a risk Alcorn was willing to take. He did not want to lose this well.

Boom or Bust

Like most other oilmen, Chuck Alcorn was still skeptical of the Austin chalk. But just in case he was onto something, Alcorn went to the Lee County Land and Abstract Company and bought 22,000 acres of leases in the area. Eventually, he also permitted a temporary shutdown of the No. 1 City. But instead of pumping mud down the hole, he used a special freezing process to stop the flow and give him time to remove the workover rig and install safer production equipment. But the nipple valve was still sticking up in the air. Too superstitious to try lowering it, Alcorn built a steel-stilt tower around the protruding pipe and connected the valve to the flow lines on the ground with a steel hose. The well looked like a football coach’s observation platform.

The No. 1 City of Giddings kept on producing its honey-colored oil at the rate of three hundred barrels a day right through the end of 1973 and on into 1975. In the meantime the OPEC nations announced their oil embargo and the first in a series of price hikes that tripled the world price of oil in eighteen months’ time. Although restrained by price controls, domestic crude prices rose from under $4 a barrel to $10 a barrel for so called new oil (oil discovered after 1972), which the No.1 City’s oil happened to be. Now wells that made as little as fifty barrels per day were becoming commercially viable; wells making a hundred barrels per day could be big revenue producers. The idea of hunting for oil in the U.S. suddenly became attractive again.

Despite the price increase and the continuing flow of the No. 1 City of Giddings, Alcorn’s discovery did not touch off an oil rush in Lee County. A small outfit called Hughes and Hughes Oil and Gas, led by a former Union Producing geologist who still had faith in the Giddings area, tried a few wells, but none were commercial producers. A couple of prominent independent operators, among them Robert Mosbacher of Houston and Clayton W. Williams of Midland, had acquired large wildcat lease blocks in the area after the earlier Austin chalk discoveries in South Texas, but they did not attempt to develop them. Even as Hughes and Hughes was having its problems in Central Texas, still another Austin chalk boom erupted with a discovery well in South Texas, then promptly fizzled out. Many investors lost their shirts. Only the oil field service companies, which provided the drilling equipment and the well stimulation treatments, came out ahead.

Since he was more of a completion and production man than a wildcatter, Alocorn did not see fit to explore the Giddings area himself. Instead, he turned to one of the hottest public oil companies in the history of the stock market, Houston Oil and Minerals Corporation (HO&M), which happened to be run by his college classmate Joe Walter. Alcorn transferred his 22,000 acres to HO&M on a “farm-out” agreement, which allowed him to obtain a substantial interest in any future production without having to put up any of the drilling costs; then he sat back to watch HO&M bring in the field. HO&M quickly drilled three wells around Giddings, but none turned out to be commercial producers.

With HO&M’s failure, the oil play in Lee County ground to a halt. The No. 1 City of Giddings kept producing steadily, but no one was able to find another well like it. Perhaps, as many people ever more strongly believed, the No. 1 City was just a freak, an isolated case of blind luck. Or perhaps, as only a very few diehards maintained, there was simply a secret to producing oil from the Austin chalk that no one had yet discovered.

The Magician

Ray Holifield had not been one of the Austin chalk’s original true believers. A wiry, bespectacled exploration geologist who chain-smoked menthol cigarettes, he had done his apprenticeship at a major oil company in New Orleans, then spent most of the early seventies as a consultant for Middle Eastern counties like Iran and Abu Dhabi. His specialty was searching for oil in fractured reservoirs.

In the summer of 1975 Holifield joined the Dallas consulting firm of La Rue, Moore & Schafer. He was accustomed to making about $20,000 a year. He had a wife and three children to support, and he was not a snappy dresser or a high liver. According to those who knew him at the time, he literally had holes in his shoes. But Ray Holifield was now ready to cash in on what he had learned over the years. His intention was to get in on some of the big wildcat plays such as the ones going on in southern Louisiana and the Rockies; he had no desire to mess with the Austin chalk. He hailed from Missouri, the “show me” state, and what he had heard of the Austin chalk booms that turned into busts did not excite him.

In the fall of 1975 Holifield met two Dallas oil promoters, Irv Deal and Max Williams. A short, blond man in his late forties, Deal was a real estate wheeler dealer who had fallen on hard times in the real estate slump of the early seventies and was now trying to make it in the oil business with a company called Windsor Energy. Williams was a stocky, balding former SMU basketball star, as well as the former coach and general manager of the short-lived Dallas Chaparrals pro basketball team. A native of West Texas, Williams was also the son of a Humble Oil field worker; he had grown up in what he termed “a Humble Oil camp.” But like Deal, Williams had no real experience as a full-fledged oil operator. Prior to organizing his U.S. Resources oil exploration company in 1975, he too had been in Dallas real estate.

Although they had sizable real estate operations, both Deal and Williams ran basically one-man shows in the oil business, with only a secretary and occasionally a consultant to help them. They operated by selling “a third for a quarter”—oil industry parlance for the standard practice of selling one-quarter interests in their deals for one third of the cost, so that the promoter wound up with a “free” one-quarter interest for himself. Their annual drilling budgets were about $1.5 to $2 million, and they raised most of their money from people who were not typical oil business investors.

Deal and Williams had lately been partners in several oil well ventures. Though neophytes, they knew enough to be aware of the old dictum that there are really only two kinds of geologists — those who find oil and those who don’t. They had heard from a friend that La Rue, Moore & Schafer had an oil-finding geologist. That geologist was Ray Holifield.

Deal and Williams tried to get Ray Holifield excited about the Austin chalk. Like most other oilmen, they could not boast of pleasant experiences with the chalk themselves. Windsor Energy and U.S. Resources had recently drilled about five wells together in South Texas near the Frio County town of Pearsall. Although they had found oil, all five wells had followed the typical Austin chalk pattern of coming in strong and drying up quickly. But Deal and Williams had heard several people mention that there was an Austin chalk well up around Giddings that was still going strong after two years. The two men begged Ray Holifield to check out the story and see if it was true. Reluctantly, he agreed.

The Texas Railroad Commission report Holifield received on the No. 1 City of Giddings nearly knocked him out of his chair. It showed daily oil production of 300 barrels for a cumulative total of more than 200,000 barrels. At the current price for new oil of about $10 a barrel, that rate translated into $2 million in gross income in two years. Suddenly Holifield started to think that maybe the Austin chalk deserved another chance after all. He studied the entire Austin chalk trend and concluded that Giddings looked like the best place to start drilling.

Close Encounters

With Holifield as their guide, Windsor and U.S. picked their first Lee County location in the summer of 1976. The well was called the M&K No. 1. Its name came from the two property owners whose land made up the lease block: H.T. Moore, a black shoe repairman then in his late seventies, and James Krchnak, a traveling paint salesman of Czech descent. Still lacking any overall theory of the Austin chalk, Holifield was going by one of the oldest and most frequently used geological concepts — “closeology.” As the term implied, the idea was that Windsor/U.S. was most likely to find oil by drilling as clse as possible to a producing well. The M&K No. 1 was spudded in approximately 2500 feet to the east of the No. 1 City, which put it just off Highway 77 at the edge of the city limits.

The second reason for picking the M&K location was money. Both Windsor and U.S. were raising their drilling funds on a deal-by-deal basis. The cost of drilling an Austin chalk well was about $320,000, a god chunk of each company’s annual budget. They were able to drill the M&K lease on a farm-out agreement from the firm of Hughes and Hughes. Although this agreement provided Hughes and Hughes with a 30 per cent interest in any future production, it enabled Windsor/U.S. to acquire the lease with very little money up front.

Holifield, Deal, and Williams then benefited from a wildcatter’s most valuable asset: good, old-fashioned luck. On October 7, 1976, exactly three years to the day after Chuck Alcorn revived the No. 1 City of Giddings, the M&K well struck honey-colored oil and plenty of it. The initial potential of the well was gauged at 467 barrels per day.

Elated by their success, the three men quickly staked two more wells, the Schkade No. 1 and the Carmean No. 1. Like the M&K, both the Schkade and the Carmean sites were chosen mostly by closeology, but with the Carmean there was a new twist: in picking the location of the well, Holifield used seismic data purchased from another company that had previously tried and failed to find oil in the area. Based on the resonances of sound waves, the data had been obtained by setting off twenty-pound dynamite charges buried at various locations some ninety feet below the earth. After passing through tapes and translation machines, the vibrations from the dynamite charges printed out on a piece of paper as a series of wavy lines layered one on top of the other, reflecting the various depths of the rock layers below the surface.

To the uninitiated, seismic charts look like hieroglyphics, but to a person trained to read them, the subtle differences in the wavy lines suggest much about what might lie beneath the ground. Because of the complexities involved, interpreting seismic is a whole profession in itself, usually performed by a geophysicist, not a geologist. But Ray Holifield was one of those rare geologists who could read seismic (he had picked up the skill while working in Louisiana). What he saw of the seismic in the area of the Carmean intrigued him, because it indicated the presence of a fault in the rock, which in turn suggested that there might be an oil trap of some sort nearby.

Again, luck seemed to be on the side of Holifield and Windsor/U.S. In December 1976 the Schkade came in, making oil at the potential rate of 783 barrels per day. That made it the best Lee County well so far. The Schkade also showed potential gas production of one million cubic feet a day. The oil well completion men danced in the glow of the automobile headlights shining on the well, hugging each other like little children. One month later, after announcing itself with a terrific blowout, the Carmean struck oil too. Though not as big a well as the Schkade, the Carmean had something else going for it: production in not just one layer of rock but two. Initial tests showed that the Carmean could produce 188 barrels of oil a day from the Austin chalk and 145 barrels a day from a deeper layer known as the Buda. This was the first indication that the Giddings field—if indeed it was a field—might have “multipay” zones of oil and gas, which would make it even more valuable.

A Question of Fault

Flying on the wings of their new discoveries, Holifield and Windsor/U.S. immediately planned to drill more wells. They also ordered seismic crews into the Giddings area to begin shooting their own seismic lines. The success of the Carmean well confirmed what Holifield had seen in the old seismic data and gave him a clue about what to go after next. In addition to looking for faults, he was searching for fracture systems, or “sweet spots,” places where the Austin chalk was fractured into thousands of tiny channels that trapped oil.

Theoretically, these sweet spots could be located almost anywhere. The one sure way to find out where they were—and where they were not—was to drill wells. But that could be quite expensive, especially since merely drilling and drilling increased the chances of dry holes. On the basis of what he had seen so far, Holifield developed a unique theory, that the fracture systems in the Austin chalk were located around faults. Through the use of seismic, Holifield could find the faults in the Austin chalk and, he hoped, the fracture systems that might be with them. The method of seismic interpretation Holifield planned to use to find the faults and fracture systems was his own trade secret. He did not explain it even to his clients.

Using Holifield’s seismic calculations, Windsor/U.S. drilled the Molly C. Davis well in the spring of 1977. Everything looked fine — until the drill bit had reached total depth and it came time to run the electrical log test to see if the well was worth completing. The test consisted of lowering an electrical measuring device into the hole to take continuous readings later printed out as parallel lines on the log chart. In oil- and gas- bearing zones, the electrical log’s two main lines, the “SP” or spontaneous potential line and the resistivity line, usually bulged out. But the lines on the Molly C. Davis log chart were almost as straight as railroad tracks. They were virtually no bulges showing oil and gas at the depths where Holifield’s seismic data predicted they should be. Windsor/U.S. had little choice but to plug the well and move on.

The next Windsor/U.S. well was called the Max Fariss No. 1. Like the Molly C. Davis, its location was selected using Holifield’s seismic charts. And once again everything went smoothly until it came time to run the log. Nothing but railroad tracks appeared on the chart. “I’ll carry out all the oil this well will ever produce in a wheelbarrow,” the tool pusher told Max Williams when he arrived on the scene.

The tool pusher appeared to be right. After three early successes it looked like Holifield and Windsor/U.S. had lost their touch. Whatever “secret” Holifield had discovered in the seismic data now seemed to be a false trail. Without seismic as their guide; Windsor/U.S. would once again be reduced to closeology and blind luck. “We were scared to death,” Holifield recalled later. “We were about to shut down operations.”

Then Holifield got to thinking. He was still confident of his seismic data, so the problem had to be somewhere else. If the Austin chalk’s oil was contained in natural fracture systems, it was quite likely that the cracks were clogged with drilling mud and natural debris. Perhaps these blockages were preventing the oil from flowing out. Down south, in the recent Frio County Austin chalk play, most of the few successful wells had been completed with a formation-opening process called hydraulic fracturing or simply “fracing.” First employed in the northern part of Central Texas in 1947, fracing was traditionally used to create fracture systems in layer of rock, but now it was being used to open up natural fractures as well. Fracing involved pumping huge quantities of sand and water down the hole. The water rushed through the clogged fractures, cleaning them out and opening them up. The sand, which shot through after the water, acted as a bracing agent for these newly opened orifices, much as wood beams buttress the ceiling and walls of an underground coal mine. Then the oil could begin to flow.

Fracing was a much bigger job than acidizing and about ten times more expensive. Fracing required setting pipe—lining the hole with steel tubing—and it required at least half a dozen trucks, huge amounts of sand and water, and all sorts of sophisticated equipment. It cost in the neighborhood of $80,000, or about one fourth as much as drilling the well. But Holifield knew that fracing was the only alternative, his only chance for turning the bad wells into good producers. Although Windsor/U.S. was already way over budget on the Molly C. Davis and the Fariss, he convinced Williams and Deal that is was worth a try.

The Big Break

The frac job on the Fariss No. 1 began in June 1977. As completion man Ted R. Ferguson described it, the operation was “like putting on a big opera.” The Western Company facing crew began setting the stage by digging a water-holding pond near the well, then hauling in three large yellow water tanks and a long yellow sand bin and lining them up several yards from the well. Next, the crew moved in an oblong blender machine, which hooked up the tanks, the sand bin, and the wellhead via a network of pipes. After that, the pumper trucks arrived, parked in a neat row at a right angle to the blender, and hooked onto the long pipe leading from the blender to the well. Finally, the frac van, the truck that housed all the control panels and the crew boss, pulled in next to the blender. With all the truck and machinery now arranged like section of the orchestra, the entire crew of twenty men put on headsets that kept them in communication with the frac van. The crew boss gave the signal for the well stimulation opera to begin, and the crew activated the blender, the water tanks, and the sand bin. The well site was engulfed by a nearly deafening whirring and clanging as the pumpers pumped and the water and sand began flowing into the hole.

Several hours later the water started to come back up, signaling the end of the process, and the fracing crew shut down. Holifield, Williams, Deal, and the drilling crew had nothing to do but wait. Then, slowly, the water began to show traces of honey-colored oil. Soon there was more and more oil in the water. The Fariss No. 1 eventually made initial production gauged at a rate of 717 barrels a day. Holifield’s secret theory about using seismic was on the mark. Just to make sure, Windsor/U.S. went back and unplugged the Molly C. Davis well and fraced it. The well came in, making 215 barrels of oil and just under half a million cubic feet of gas a day. “By this time,” Holifield recalled, “we were thrilled.”

Windsor/U.S. started drilling more wells, based on the new seismic it had shot since arriving in the Giddings area. Both the Schneider No. 1 and the Dean No. 1 struck oil, with the Schneider making a big producer. Now things were really rolling.

Then Deal and Williams had a falling-out. Their disagreement apparently revolved around who was raising the most money to drill and who was doing the most work for their mutual interests. Concluding that the could live better separately than together, Windsor Energy and U.S. Resources got a divorce in October 1977. From that time forward, Windsor and U.S. had only one thing in common: each company continued to consult with the only man who seemed capable of finding oil in the Austin chalk—Ray Holifield.

Holifield, for his part, tried to keep things quiet. He did not brag about his good wells, and he did not publish any professional papers explaining his theory of the Austin chalk. If larger and more experience companies realized what was happening, they would be able to gobble up adjacent leases ahead of Windsor and U.S. Resources. And if another bright geologist figured out how to use seismic to find the sweet spots in the chalk. Holifield would no longer have a monopoly on technical expertise. Instead of sharing his knowledge of the area as geologists often did, Ray Holifield kept to himself. He was what oilmen call a “tightholer.”

Tightholer or not, Holifield could not completely suppress the news about his clients’ big strikes in the Giddings area. Oil people talk. Landmen, tool pushers, roughnecks, and completion men all love to brag about hitting a good well. Fortunately for Windsor and U.S. Resources, the ingrained skepticism oilmen had for the Austin chalk kept most of those who heard about the play on the sidelines. But even as Irv Deal and Max Williams were bringing in their first wells under Ray Holifield’s direction, another small but very shrewd independent operator managed to get in on the play, too.

The Humble Man

Pat Holloway did not pretend to be humble. Tall, blue-eyed, and fortyish, with strawberry-blond hair that tended to rise in wisps from the top of his head, Holloway had been a high achiever all his life. Born in Brownwood and schooled at both Texas Country Day School (now St. Mark’s School of Texas) in Dallas and R. L. Paschal High School in Fort Worth, he had done two years of undergraduate work at Yale. Then he had returned to Texas to enter an accelerated undergraduate and law school program at UT that enabled him to get his degrees in fewer than the standard seven years. After law school he had gone into private practice as an oil and gas attorney.

Holloway had the oil business in his blood. His grandmother had been the manager of Gulf Oil’s operations in a five-state area back in the early 1900s. His father had been an oil and gas attorney. Thus Holloway thought he had a certain feel for the oil game. In representing oil companies and drilling funds throughout the sixties and early seventies, Holloway seldom hesitated to express his opinions about his clients’ oil ventures. Finally, one day in 1975, Holloway’s best friend, Frank West, started teasing him about his outspokenness. “You keep making nonlegal decisions,” West said, “and it’s ruining my business. Why don’t you go into the oil business for yourself?”

Holloway decided to do just that. Resigning from his law practice, he took some of the money he had accumulated and built a large house in North Dallas as a hedge against both inflation and failure. The house was also the site of his first office as an oil and gas operator. With his wife, Robbie, as his secretary, Holloway began raising his own drilling funds. He christened his new enterprise Humble Exploration Company. The name, Holloway claims, had nothing to do with Exxon, the former Humble Oil & Refining Company. Rather, as Holloway later explained in a letter to Exxon, it was arrived at “one evening over drinks” when Holloway and his partner, Bill Browning, “after temporarily exhausting the subject of women,” turned to consider their recent decision to go into the oil business. “We decided that it would be advisable not only to adopt an attitude of humility but also, as an added safeguard, to remind ourselves daily of the desirability of that particular attribute by reference thereto in our corporate charter.”

Holloway and Browning originally aimed Humble Exploration at the big oil play in the Williston Basin of Montana and the Dakotas, and despite some hard going at first, found production in six Western states and Louisiana. But it did not take long for Holloway to get interested in the Austin chalk. In the summer of 1976 Irv Deal came to Holloway and offered him a chance to get in on the M&K well, which was due to be drilled that fall. Although Holloway rejected Deal’s offer, he did go to Hoilfield to find out what was going on.

“I can’t talk to you about it,” Holifield said, wary of getting caught between conflicting interests.

Holloway did not press the matter, but he kept his eye on what was happening around Giddings. In September 1976 Browning died unexpectedly, leaving Holloway with practically a one-man operation. When Windsor/U.S. brought in the M&K well in October, Holloway decided to get into the play after all. At the time it looked like most of the prime acreage in and around Giddings had already been leased up. Noticing that seismic crews were suddenly showing up in Giddings, Holloway surmised that Holifield, Deal, and Williams were “up to something,” and decided to lease up the only available acreage remaining, which was the land around the railroad tracks that ran through the town in four directions. Then he went back to Holifield and started bugging him for help.

Holifield finally relented. “Look,” he told the persistent Holloway, “I can’t work for you around the city of Giddings because that’s where my clients have their acreage. But you know that the trend runs from Mexico to Louisiana. The leases may be just as good out in the country.”

Taking the hint, Holloway began looking around for leases outside Giddings. He was in the Lee County Courthouse searching through records one day when a fat, crew-cut German American farm boy in his late twenties approached him with a question.

“Is it true that there’s going to be an oil boom here, mister?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Holloway answered.

“Well,” offered the young man, “if you teach me how to run these records I’ll work for you for free.”

The farm boy’s name was Bennie Jaehne. In addition to being a local boy born and bred, Jaehne had run a welding shop in Giddings and was the hay cutter for many of the farmers in Lee County. He knew where everybody lived and who owned which tracts of land. And that, as Pat Holloway soon recognized, made Bennie Jaehne a natural landman. After some instruction from Holloway, Jaehne started tracing the heirs and owners of property around Giddings and leasing their land for Humble.

Holloway, who had still not drilled his first well around Giddings, soon became embroiled in a battle with the operators who were drilling wells in the area. The controversy centered around a Texas Railroad Commission field rules hearing in February 1977. At that time, the active operators —— Windsor, U.S. Resources, Chuck Alcorn, and HO&M —— were drilling under field rules requiring wells to be spaced 40 acres apart. Fearing that continuing to space their wells so close together would cause them to drain each other’s reservoirs, they were applying for rules that would require wells to be spaced 160 acres apart. Holloway, whose holdings consisted primarily of about 20 acres of in-town leases, saw a 160-acre spacing rule as a potential death blow, because it would not permit him to drill enough wells to develop his own leases profitably.

Holloway hired noted Dallas landman Sam King and launched a counteroffensive. The first move was the formation of an ad hoc group called the Lee County Royalty Owners Association. Taking out an advertisement in the Giddings Times & News, King portrayed the request for 160-acre spacing as a “conspiracy” by the “major oil companies” to deprive Lee County landowners of their rightful revenues. (The ad did not mention that the companies that wanted the rule change were really small independent operators like Windsor and U.S. Resources.) When the day of the Railroad Commission hearing arrived, Holloway and King hired a bus to transport a group of local citizens to Austin and provided each passenger with a fried chicken lunch.

The show of popular sentiment proved decisive. After listening to the arguments, the Railroad Commission issued a compromise ruling that allowed eighty-acre spacing with an option for forty-acre spacing. Holloway’s political organizing effort had saved the day for Humble Exploration, but it did nothing to endear him to the other operators in the area. To many, Pat Holloway became known as the bogeyman of the Giddings oil play.

With the furor over the field rules hearing still fresh in everyone’s mind, Holloway began going after the acreage he really wanted —— leases outside Giddings. The first block he acquired was a 3500-acre package of wildcat leases located about ten miles northeast of Giddings toward Dime Box. Holloway got the leases on a farm-out agreement from Houston oil operator Robert Mosbacher. Then, with Holifield’s help, Holloway persuaded Columbia Gas System, an East Coast utility company that was beginning an onshore oil exploration program, and Mary Kay Cosmetics of Dallas to put up a little more than $1 million to drill two wells in the Austin chalk.

Swap Feat

About this same time HO&M, which was now playing off the success of the Windsor/U.S. wells, drilled a well within the city limits of Giddings. As the drill bit reached total depth, the well “took a kick”—oil talk for a sudden uncontrolled flowing of oil and gas—which threatened to cause a blowout. The HO&M crew immediately closed the blowout preventers. Four days later HO&M ran a log and sent the results to the Houston office. Then HO&M’s landmen began competing with Humble Exploration for leases inside the city. As lease prices escalated from $50 to $75 to $100 per lot, Holloway started to buy tracts on the perimeter of the city, attempting, as he put it, “to head ‘em off at the pass.” Yet he still didn’t know exactly why HO&M was so interested in in-town leases. Soon HO&M sent a junior landman to Holloway with an offer to buy his in-town leases. Holloway resisted. The HO&M emissary finally burst out in frustration, “You don’t understand. I’ve got instructions to get you out of Giddings.”

Holloway knew HO&M had made lots of money elsewhere in Texas by drilling in the Wilcox sand, a layer just above the Austin chalk. Remembering that HO&M had not logged its most recent well within Giddings until four days after the well had come in, Holloway suddenly realized what was going on. While the well had been capped, gas from the Austin chalk layer had seeped up into the Wilcox layer. HO&M must have thought that Giddings was sitting on top of a billion-dollar gas field —— in the Wilcox sand, not the Austin chalk.

Holloway saw a chance to turn HO&M’s error to his own advantage. Since HO&M was so eager to acquire in-town leases, he proposed a trade: his 20 acres of in-town lots for 2500 acres that HO&M owned outside the city. HO&M gladly agreed. The deal brought Humble’s total lease stake in the Giddings area to about 6000 acres.

Holloway then came to blows with a much larger foe. In the summer of 1977 Exxon filed a $1 million suit against Humble for alleged trademark violation, claiming it still operated three companies that used the name Humble. Holloway responded by gibing in a letter to Exxon, “We have grown accustomed to our name, and respectfully decline to change it at your request. Stated somewhat more strongly, we doubt we would be willing to make an ‘even swap’ of names with you even if you were to make such an offer.”

By November 1977 Holloway was finally ready to drill his first well. It was called the Burttschell No. 1 after local leaseholder Elder Burttschell, and it was located about ten miles north of Giddings on the farm-out acreage acquired from Mosbacher. Since the site was so far out of town, it was regarded as a “stepout” well, a wildcat attempt to extend the boundaries of the Austin chalk play.

Just before Christmas the Burttschell came in like an old-fashioned gusher. A thick stream of honey-colored oil shot right up over the top of the crown block 120 feet off the derrick floor. The entire crew and much of the surrounding countryside were bathed in oil. But there was no delirious dancing in the rain of liquid money. The Burttschell was a full-fledged blowout, an oil well gone amok. Besides wasting precious oil, it could catch fire. The crew had to get the well under control. Unfortunately, this was the first well Humble Exploration had ever operated, and no one really knew what to do. They had struck oil, but they had also awakened a monster.

Day after day Holloway and his crew struggled to bring the Burttschell under control. It was cold and rainy, and the men huddled anxiously in Schubert’s restaurant, trying to figure out their next step. Finally, in early 1978, after ten days of the well’s rampage, they managed to stop the blowout by dropping “pills” —— super-heavy drilling mud mixtures —— down the hole.

After it was controlled, the Burttschell No. 1 was tested to have potential oil production of 1084 barrels a day and potential gas production of nearly half a million cubic feet a day. What was more, it showed that the Austin chalk play was not confined to the city of Giddings but had all the earmarks of a sizable oil field.

Thirty Miles of Play

Under ordinary circumstances, a well like the Burttschell No. 1 would have touched off an oil rush as dramatic as the blowout it had come in with. But the Burttschell was, after all, an Austin chalk well. Despite its impressive potential and the success of the Windsor and U.S. Resources wells, many oilmen in Houston and Dallas remained cautious. They expected the Burttschell to dry up. Besides, as the Houston and Dallas oil fraternity understood it, much of the land in Lee County had already been leased. There was very little room to get in on the play even if they wanted to. Or so many of them believed.

Humble, Windsor, and U.S. did not remain the only operators in the field. In addition to the five other companies that had already drilled wells around Giddings, no less than sixteen newcomers joined the play, among them the Superior Oil Company and K. S. “Bud” Adams, Jr.’s, Ada Oil Company of Houston. But if these new entrants increased the competition and the drilling activity in the field, they hardly constituted a full-fledged oil rush. Humble, U.S., and Windsor still had plenty of room to operate.

After the Burttschell, Humble quickly drilled two more Lee County wells. The first, called the Perkins, made a relatively modest 150 barrels a day, then began to drop off. The second, the Kocureck No. 1, turned out to be another whopper. Initial potential was calculated to be 1003 barrels of oil a day. Located even farther north than the Burttschell, the Kocurek extended the Giddings field up to the Burleson County line.

Windsor, under Holifield’s direction, brought in seven producing wells in 1978. Five of them were definitely commercial, though a little disappointing. But two others came in with a potential of more than 1000 barrels of oil a day each. U.S. Resources did even better with a big strike on the three-thousand-acre Gerdes Ranch, between the Burttschell and the Kocurek, that proved to be a harbinger of many wells on the property.

In the summer of 1978 Humble began another stepout well. This time the drilling was to the south of Giddings rather than to the north. Located in Fayette County just above the town of La Grange, the well was called the Chicken Ranch No. 1 after the infamous local brothel that had just been closed down and was soon to be immortalized in a musical comedy. Although the well was not actually located on the old Chicken Ranch property, Pat Holloway liked the name and thought it might bring good luck. Instead, it seemed to bring just the opposite. When the Humble men reached total depth and ran a log, they got only railroad tracks —— no shows, no signs of faulting, nothing.

“Normally, you wouldn’t have set pipe if you’d looked at the log,” Holloway admitted later. “You would’ve plugged the well. If I had shown the log to my partners, they would’ve voted no.”

But Holloway put his trust in Ray Holifield. And Holifield told him there was a fault —— which suggested a fracture system containing oil —— just below the total depth to which the well had been drilled. Holifield wanted to set pipe on the well and frac it, as Windsor/U.S. had done with the Fariss and Molly C. Davis wells. That would involve still more financial risk, but Holloway decided to abide by his geologist’s counsel.

Humble’s hopes were fulfilled. In early September 1978 the Chicken Ranch No. 1 responded to its frac job by coming in at a potential rate of 1353 barrels per day. The well was, as Holloway said, “a real barnburner,” not to mention the most productive ranch property in the county since Miss Edna and her girls had been shut down. Even more important than its immediate success was the fact that the Chicken Ranch No. 1 marked a significant extension of the Giddings field. The distance from the Chicken Ranch No. 1 in Fayette County to the Kocurek No. 1 up by the Burleson County line was a good thirty miles.

Missing Maps and Unknown Heirs

While drilling their wildcats, Ray Holifield’s three independent clients also snatched up the three biggest and best acreage positions in the area. This they did by luck, cunning, and assistance from local insiders. Lee County was not all leased up by the time Humble brought in the Burttschell well —— it just looked that way. As Pat Holloway observed, the standard lease maps for the area were “all screwed up.” Large portions of the land around Dime Box were owned, or at least settled, by poor black families. Titles passed down through the generations were often unclear, and there were many missing heirs. To make matters worse, some of the maps that belonged in the Lee County Courthouse had disappeared, and many of those that remained were out of date.

The confusion over the Lee County maps apparently revolved in part around a family of local land experts named Knox. The late patriarch of the family, John Knox, Sr., had been the county surveyor as well as the owner of the Lee County Land and Abstract Company. According to Knox’s twin sons, John and Robert, two sets of Lee County maps were made in the early part of the century —— one set for the county and one set for the private abstract company that their father later bought. John Knox, Sr., kept his own maps in good order. The county’s maps, however, were not kept current. When John Knox, Sr., died, his son Louis Knox became county surveyor, while the Knox twins took over the family business and their father’s maps.

Prompted by complaints about the missing and out-of-date county maps, the Lee County Commissioners’ Court passed a resolution in October 1977 asking county surveyor Louis Knox to make sure that all maps, plats, and surveys belonging to the county were in fact in its possession. The commissioners also asked the Knoxes to provide all of their father’s working papers. Louis Knox replied in a letter that his father did not keep any working papers. In a separate letter from the Lee County Land and Abstract Company, John and Robert Knox also told the commissioners that their father did not keep working papers and suggested that the commissioners consult the county deed records if they wished to bring the county maps up to date. Still concerned about the confusion, county judge Carey Boethel brought the matter to the attention of Attorney General John Hill’s office. But the complaint lapsed without further official action.

Meanwhile, the Knox twins used the only privately owned Lee County maps —— the set reportedly made for the abstract company —— to cash in on the oil lease title work that accompanied the oil boom. They also got in on the action by acting as landmen and assembling oil lease blocks for operators interested in drilling wells in Lee County.

Falling back on his legal training, Holloway, for one, decided to do his title and abstract work himself. With Bennie Jaehne doing the legwork, Humble started acquiring more leases outside Giddings. The going rate was an up-front fee of $25 per acre and a one-eighth to one-sixth share of any future production; though low by comparison to those of some other oil plays, these prices were then top dollar for the Giddings field. Jaehne, for his part, got 0.5 per cent overrides on each of the leases he obtained for Humble. Thanks largely to him, Humble kept acquiring leases in 500-acre chunks. Eventually the company had more than 178,000 acres in Lee, Fayette, and Gonzales counties and surpassed both U.S. and Windsor to become the largest leaseholder in the field.

About this time Holloway applied for new field rules requiring 160-acre spacing, the very thing he had fought against only a year or so before. Now that he had acquired much more acreage, he did not want to deplete his reservoirs by drilling too many wells too close together. As he blithely admitted afterward, he went before the Railroad Commission and “proved conclusively” exactly what he had disproved conclusively before.

These early days, Holloway observed, were “a curious mixture of war and peace.” Competition for leases was fierce among the three Holifield clients, Humble, U.S., and Windsor, with each badmouthing the others in an effort to win over the landowners. “I’d cut their throats to get leases,” Holloway recalled, “and they’d stab me in the back.” Bennie Jaehne soon adopted the practice of leaving courthouse books open to pages for an area completely different from the one he was interested in so that the competition, who were always looking over his shoulder, would be misled. Holloway would not discuss business with Williams or Deal. Having started out as coventurers, Williams and Deal now became archrivals. But for all the bad blood in the triangle, the three companies also came to each other’s aid. If one of them had a blowout, the others would send men to help get it under control. If one operator was short of mud or pipe or equipment —— and shortages were the rule in the early days —— the others would swap and share.

Besides competing with each other, all three fought together against the pipeline companies. At this stage there were still relatively few pipelines in place, so much of the oil was picked up from the storage tanks by truck. Field operators suspected that some pipeline company well gaugers stole enough oil to cover their salaries each month, allegedly by cheating on the amounts of oil they reported finding in the storage tanks. Since one inch of oil in a five-hundred-barrel tank was the equivalent of twenty barrels, worth $600 to $800, the corrupt gaugers could play a game of fractions, pinching a very small amount from each well by misreporting the numbers on the measuring reel they dropped into the tanks. The field operators countered by dispatching their own gaugers to check up on their storage tanks’ contents.

Of course, the greatest common fight for Humble, U.S., and Windsor was the war against the field itself. Even when Ray Holifield’s geology was right on the mark, drilling the Austin chalk was difficult. Since the wells, if they were good wells, often started flowing fast and unexpectedly, they had to be watched closely 24 hours a day throughout the drilling process. And because of the high pressure in the Austin chalk, there was the constant threat of a blowout or a fire. Twice, huge balls of flame from Humble wells filled the Giddings sky.

With the going rate per barrel of new oil soaring to nearly $40, a new drilling boom had commenced in the United States. There was not only a shortage of rigs and equipment but also a shortage of competent, experienced drillers. In the tradition of the wildcatters of yesteryear, Pat Holloway did the lion’s share of his company’s work himself. He spent the daylight hours out in the field, leasing bulldozers to clear locations, renting drilling rigs, and supervising drilling operations. At night he would drive back to Dallas and do his own title work. For Humble, the development of the Giddings field truly became a family affair. While Holloway’s wife, Robbie, continued to do the secretarial work in Dallas, his 24-year-old daughter, Marcy, left her job at an Austin bank to join her father’s Giddings operation. At the time Marcy was the only woman in the area who actually worked out in the oil fields. As a gauger, her job was to drive a route of fourteen producing wells and check the tank batteries and production equipment of each. Though she had no previous experience in the oil business, she soon picked up all the tricks of starting heater treaters, climbing storage tanks and operating oil tank measuring reels. Marcy’s teenage brother, Patrick, later joined her in the field. It was definitely an exciting, adventurous enterprise for the Holloways, but it was also the sort of work that would take its toll on the family in the months to come.

Though Irv Deal tended to delegate more work at Windsor, Max Williams did almost as many jobs at U.S. as Holloway did at Humble. Williams customarily spent his nights on his oil rigs, then changed out of his Levi’s and into his business suit and returned to Dallas to raise money and do paperwork during the day. As he remembered, “I got about two or three hours’ sleep a night.”

Ray Holifield also worked like the devil. With three clients active in the field, he had a never-ending stream of seismic data to analyze and locations to pick. After putting in fourteen-hour days in Dallas during the week, Holifield would drive to Giddings each weekend and visit every well in the field.

By mid-1978 several other wily competitors were eyeing or had already entered the Giddings field. Thomas D. Coffman of Austin brought in his first Lee County well in the summer of 1977, then drilled seventeen more producing wells in the next eighteen months. Though not a client of Ray Holifield’s, Coffman and his in-house geological staff were developing their own parallel method of seismic interpretation for finding the sweet spots in the Austin chalk. The most flamboyant competitor was Clayton W. Williams of Midland. A dashing, wealthy oilman and rancher, Williams was a devout Texas A&M graduate. He owned a swimming pool shaped like an Aggie boot and flew an Aggie banner atop all his drilling rigs. He was also reputed to be his alma mater’s largest individual benefactor. Williams swooped into Giddings in the summer of 1977 and started spudding wells on the leases he had acquired a few years earlier. He talked to Ray Holifield, but the two could not come to a working agreement. Relying on guesswork and closeology, Williams proceeded to drill four wells in 1977 and 1978. Two of the wells were dry holes, and a third was marginal. Only the fourth turned out to be a decent producer. Undaunted, Williams determined to drill more wells in the area.

Houston Oil & Minerals also tried to retain Holifield. But when Holifield asked for a 2.5 per cent override, HO&M balked. The company’s next drilling ventures resulted in still another string of poor holes in the Giddings field, and shortly thereafter, HO&M came back to Holifield and agreed to pay him his override.

The demand for Holifield was understandable. By the end of 198 there were 150 producing wells in the Giddings field; three years earlier there had been only 1 to speak of, the No. 1 City of Giddings. Of those 150 wells, 75 belonged to Holifield’s three principal clients. Counting all the wells in the area, the Giddings Austin chalk field was now producing more than 14,000 barrels of oil each day. Together Humble, Windsor, and U.S. were already producing an average of 9615 barrels of oil, or the equivalent of $350,000, each day. With only a few exceptions, those who did not have Holifield’s services drilled mostly dry holes. But Humble, U.S., and Windsor hit oil on an unheard of nine out of ten wells; seven of every ten wells they drilled were commercial producers. As most everyone acknowledged, the reason for that phenomenal success rate was the genius of Ray Holifield.

The Boom Is On

In early 1979 the oil people finally descended in force upon the little town of Giddings. They came by airplane, automobile, and freight train, in Cadillacs, Broncos, pickups, pumper trucks, and tractor trailers. Some even came on foot from hundreds of miles south. They represented every class and station of the industry. There were promoters, geologists, geophysicists, landmen, lease hounds, lawyers, tool pushers, completion men, pipeline crews, logging crews, mud crews, frac crews, and acid crews. There were also droves of plain old ordinary rough necks, most of them young men in their twenties or early thirties, many of them long-haired Anglos and undocumented Mexicans, some of them veterans of drilling booms in Alaska, Louisiana, and the Rockies. By the time the word was out: the Giddings Austin chalk oil boom was for real.

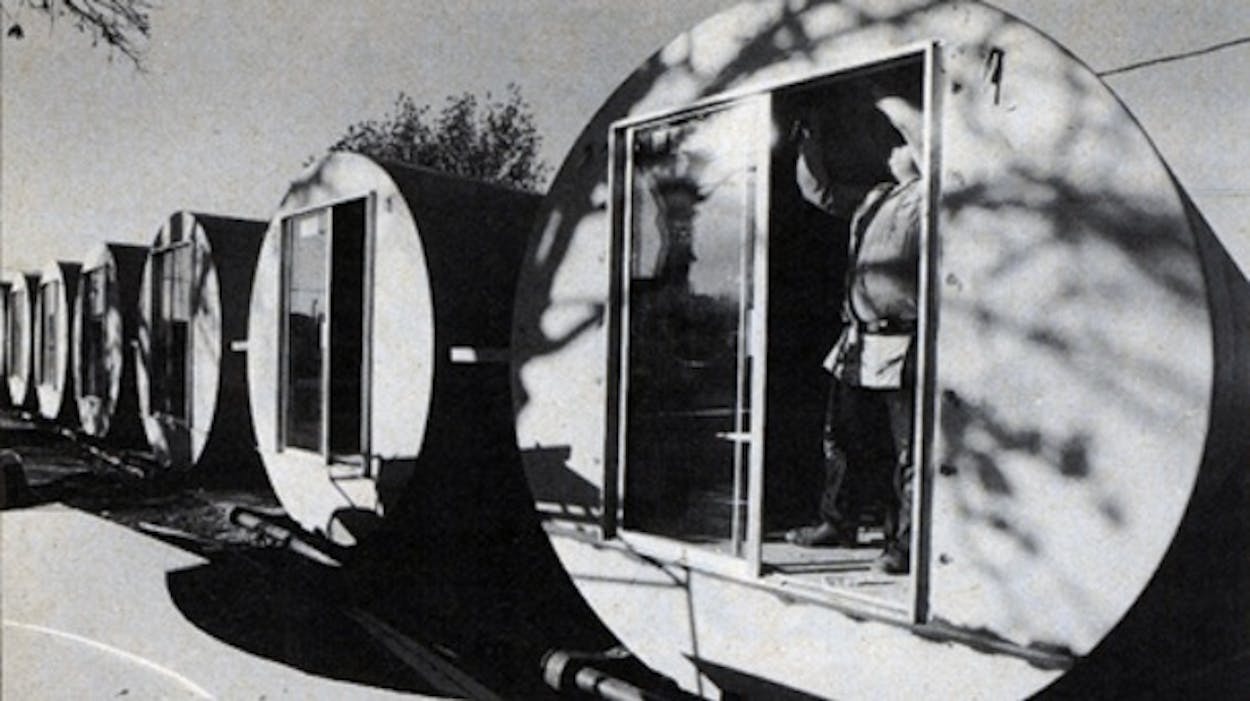

The people of Giddings could hardly believe their eyes. The city’s four small motels were overflowing; so were the two trailer parks. Ever rent house was occupied. Out in the oil fields, people were sleeping in tents, in their cars, and in every halfway suitable shanty. To accommodate his employees, Clayton Williams built his own trailer-park town just outside the city limits. It had an office building, a helicopter pad, and a gravel road marked with a sign reading “Williamsville, Speed Limit 15 mph.” Later, Dub Dixson, the owner of Schubert’s restaurant, installed a row of turned-over oil storage tanks next to his restaurant and began converting them into motel rooms, intending to rent them out for $24 a night, including board at Schubert’s.

Up to this time, the Giddings field had been the province of fewer than thirty companies. Now the number of operators swelled to more than one hundred. Though most of the newcomers, like those before them, were independents, their ranks eventually included no less than mighty Exxon. By trial and error the new players learned what Ray Holifield and his clients had already discovered—that the Giddings field was like no other they had ever encountered. Usually oilmen find gas “up dip,” closer to the surface, and oil and water “down dip,” or deeper. This pattern occurs principally because gas and oil are lighter than water. But in the Giddings Austin chalk play the laws of nature seemed to be reversed. The drill bit found water and oil up dip and gas down dip.

The newcomers realized that the Giddings field was not a continuous underground layer of oil-producing areas but a garden of sweet spots, some interconnected with other fracture systems and some more or less isolated. Each well was like its own separate field. Instead of being either horizontal or vertical, fracture systems containing oil tended to lie at an angle like the fingers of an upreaching hand. The fracture systems could be two hundred feet thick, depending on the thickness of the chalk, but they were a very narrow target, perhaps only two hundred to three hundred feet wide. For that reason wells had to be drilled exactly above the spots where the seismic data indicated the fault or fracture systems to be. Closelogy did not necessarily work. A dry hole could easily be drilled within a few years of a terrific producer.

For the explorationists themselves, the independents and majors who were actually financing this great oil hunt, there was plenty of excitement but also plenty of risk involved in drilling the Austin chalk. The risks increased in 1980 with President Carter’s imposition of the windfall profits tax. Though still regarded as new oil, eligible for sale at the world market price, the per-barrel value of oil from the Austin chalk effectively dropped from a high of $39 to about $30. That did not stifle the Giddings oil boom, but it did mean that it would take more good producers to make up for losses on dry holes. As Ray Holifield put it, “We started being a lot more selective about where we picked to drill after windfall profits.” And due to rapid inflation of drilling expenses, even a shallow well cost about $650,000 to complete. Deeper wells cost $1 million and more.

For roughnecks and laborers the Giddings boom was a godsend. In most cases a new field laborer merely had to show up for early breakfast at Schubert’s or Dub’s Grill and a job was his for the asking. Some mornings it wasn’t even necessary to ask. Crew bosses would line up in front of the restaurants, shouting to passerby, “Hey, buddy, how much do you make? Whatever it is, I’ll double it.”

Drilling activity picked up at an astounding pace. By late 1979 there were more than 250 wells in the Giddings field, and 50 rigs running. By the fall of 1980 there were over 700 producing wells, and more than 80 rigs running. Two hundred wells were drilled in the field in the summer of 1980 alone. Because of the Railroad Commission spacing requirements the wells did not stand toe to toe as in the boom days of old, but they did cover the countryside in checkerboard fashion as far as the eye could see. No longer confined to the area around Giddings or to the town of Dime Box, the field now reached into seven counties —— Lee, Burleson, Fayette, Gonzales, Washington, Brazos, and Bastrop.

Giddings remained the capital city of the field. By its own reckoning, Lee County had been one of the ten poorest counties in Texas before the oil boom. Now bank deposits in Giddings were growing by $1 million each month. Sales tax receipts soared. The city, the county, and the school district, which shared both directly and indirectly in the boom, watched their treasuries more than double.

The oil boom spawned a whole new crop of homegrown millionaires. The Gerdes family soon found its property dotted with no fewer than twenty separate oil wells and crisscrossed by 35 miles of underground pipelines. Instead of facing dire financial problems because of inheritance taxes due on the patriarch’s estate, the Gerdeses began receiving an income estimated to be in excess of $200,000 a month. Elder Burttschell, the former county official on whose property Humble drilled the decisive Burttschell No. 1, was making more than $25,000 a month. Bennie Jaehne, the former hay cutter turned landman for Humble, built his collection of 0.5 per cent overrides on the Humble leases into assets worth more than $1 million. The Knox twines of the Lee County Land and Abstract Company compiled overrides reputed to be worth that much or more. There was even a young state trooper named Jimmie Luecke who parlayed an oil discovery on the family land into more Austin chalk oil investments and found himself driving his patrol car down the road to a seven-figure fortune of his own.

The oil boom did not create any millionaires among the black residents of Lee County, but several poor black farmers did profit handsomely. Humble drilled a well on John Hancock’s property in Post Oak that brought him $50,000 in income over the next eighteen months. U.S. Resources drilled a well on Quinton Donovan’s land that made a steady four hundred barrels a day, enough to provide him and the seven other family members who shared in the property an income of more than $150,000 in only a year.

Remarkably enough, the new money seemed to do little to change the lifestyles of those who got it. The Knox twins bought a pair of black Lincoln Continentals, and one of them started letting his gray crew cut grow out. Bennie Jaehne got divorced and let his hair grow a little too. Jimmie Luecke resigned from the Department of Public Safety to go into oil full time. Quinton Donovan built a new one-story brick house right behind the white frame shack he had lived in for most of his 79 years. But these changes were about as extravagant as it got. As one Giddings resident put it, a Cadillac dealer would have starved before the boom, and he would have kept right on starving after it.

Of course, the oil boom did not bring only honey-colored happiness and light. It also brought an estimated 7500 newcomers to the Giddings area, which quadrupled the local population and created a whole new set of problems. The cost of living in and around Giddings shot up like a gusher. Before the boom a full meal at a local restaurant could be had for under $3. Now the same meal cost $5 or $6. Groceries, gas, clothes—everything went up. One local store owner candidly admitted to a friend, “The only things I have to watch my prices on are beer and cigarettes. The oil people don’t know what anything else is supposed to cost.”

Giddings did not become a bawdy house and gambling hole like some of the Texas boom towns of yore. A couple of vice trailers did attempt to set up operations in the outlying areas of the county, but Sheriff John Goodson quickly cracked down, and the whorehouses on wheels moved on. Still, as the population rose, so did crime. The Lee County sheriff’s department reported a 100 per cent increase in cases of disorderly conduct and simple assault last year.

Along with the jump in conventional crimes came a whole new kind of crime: oil field theft. The sheriff’s office was recording about five cases of equipment theft each month by the summer of 1980, but according to several oil field sources, those figures reflected a mere fraction of what was going on. Small gangs and freelancers were raiding the oil fields for trucks, tools, pipe, bits, drilling mud, and, of course, oil. Some said the value of the illicit oil field traffic amounted to several thousand dollars a month.

The oil boom also brought cries that the land was being ravaged. These protests came not from nonresident environmentalists but from the local farmers and landowners. They accused the oil companies of knocking down trees, breaking fences, rutting roads, polluting creeks and ponds, and spoiling deer stands. Most controversial of all were the pipeline companies that came armed with powers of eminent domain and began digging up the countryside to lay underground lines. Still other complaints revolved around Perry Gas’s plan to build a natural gas processing plant near a cluster of residential ranches just outside the Giddings city limits and Texas Refining’s proposal to erect a 10,000 barrel-a-day oil refinery in the same area.

Although many of the county people were benefiting directly or indirectly from the new oil money, the boom did not make every man a king. H. T. Moore, the old shoe repairman who shared in the M&K well, grossed a few thousand dollars but had to keep on repairing shoes. Many Lee County residents had no oil on their property at all; others discovered to their dismay that they or their ancestors had lost the mineral rights to their property back in the Depression, when an outfit called Texas Osage acquired 32,000 acres of Lee County land in a controversial royalty pool arrangement.

The one universal complaint about the oil boom was that it increased traffic. No longer a sleepy little crossroads, Giddings teemed with cars and heavy equipment trucks by day and by night. Besides being inconvenient, the traffic was dangerous, especially on oil-well-lined FM 141 to Dime Box. Between early 1979 and the summer of 1980 there were 35 accidents and three fatalities on that road. Local folks began calling it Death Alley.

Reaction to the encroachments of the oil boom was as varied as the citizenry of the seven-county field area. Some residents formed ad hoc protest groups to oppose the oil and pipeline companies, but many expressed their disapproval individually. One Lee County lady who lived barefoot in a shanty out in the country beat a pair of big rocks together to express her outrage when oilmen crossed her property. Several Lee County landowners pulled guns on—but did not shoot—allegedly trespassing oil workers. Fallout from the oil boom also spilled over into Fayette County. V. A. “Boss” Hrbacek, owner of the Cottonwood Inn in La Grange, told a reporter for the Austin American-Statesman that he’d “rather have the Chicken Ranch any day than pipeline trash.” Although Hrbacek later denied his statement, some good citizens of Giddings who supposedly welcomed the influx of oil money allegedly conspired to ostracize what they considered oil field trash from church and social positions.

Most of the protests were lodged by a small minority, but they represented a profound ambivalence shared at least in part by nearly every Lee County native. The people welcomed the prosperity of the oil boom. Many also welcomed the oil boomers. But they still had serious reservations about the way oil was changing their towns and their lives. One Giddings store owner expressed their ambivalence succinctly when he exclaimed, “Damn the oil companies! Damn the pipeline companies!” and in the very next breath said, “I have nothing bad to say about the oil people. Their checks are almost always good.”

The Real Money-makers

Pat Holloway is in many ways the H. L. Hunt of the Giddings field. A man of cunning and controversy with an unflagging sense of humor, he has emerged as the individual big winner of the boom. Although he was the last of Ray Holifield’s three principal clients to get into the Austin chalk, he has capitalized on the play better than anyone else. By the end of 1980 Humble Exploration Company had a cumulative oil production of more than 6 million barrels and a cumulative gas production of more than 6 billion cubic feet, or the equivalent of nearly $250 million in revenues after the windfall profits tax in only three years. No longer just a family affair, Humble employs more than eighty people. In 1981 the company will be getting half its drilling budget, roughly $45 million, from Texaco. Of the income generated so far, Holloway himself has a claim on an estimated $30 to $40 million.

Holloway also took Humble into and out of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy between the fall of 1979 and the spring of 1980, a period when his company’s oil production was reaching new peaks every day. The reason for the unlikely bankruptcy was a fight over the estate of Holloway’s late friend and partner, Bill Browning. Though primarily a technical legal tactic, Holloway’s decision to have Humble file bankruptcy only added to his image as the most controversial operator in the Giddings field.

The string of controversies continued last December as Exxon’s suit against Humble for alleged trademark violation went to trial in Amarillo. By that time Exxon had dropped all monetary damage claims and was merely asking the court to require Holloway’s company to stop using the name Humble. The trial lasted four days. A decision is still pending.

But Holloway’s adventures in the Giddings Austin chalk field have also been marred by personal tragedy. While driving down FM 141 one day in the fall of 1979, Holloway’s daughter, Marcy, swerved to avoid an animal in the road and crashed into the side ditch. The accident paralyzed her from the waist down. Holloway’s son, Patrick, crashed on the same road a short time later; although he survived, two steel plates had to be inserted in his leg to mend his injuries. On top of all that, last fall Holloway’s wife, Robbie, filed for divorce.

The second-ranking producer in the field, Max Williams’s U.S. Resources (which had been renamed U.S. Companies), has pumped out a total of more than 5 million barrels of oil and more than 20 billion cubic feet of gas, or roughly $200 million worth of energy, since 1976. Success came to Williams before he knew it. As he put it, “I was broke, I was broke, I was broke, then I was rich. There never was a time when I sat down to think what was happening. I never said, ‘By God, I’ve got it made.’” But as Williams now admits, he does have it made. He and his wife and two children have moved into a big house in Dallas with a swimming pool, tennis courts, and three acres of land. He flies about in a Citation, a King Air, a helicopter, or one of the two single-engine planes his company owns.

By all appearances, the Giddings Austin chalk play has been good to Irv Deal, too. Windsor Energy ranks third in the field behind Humble and U.S., with cumulative oil and gas production in the last four years worth over $100 million. According to his former partner, Max Williams, Deal has been spending much of his time away from the office. According to Deal himself, he works just as hard as he always did. Still active in real estate, he claims to be the second-largest residential developer in Nevada. He also holds, through Windsor, 100,000 acres of leases in the Austin chalk trend and will have a $60 million drilling program this year, which will include not only Austin chalk wells but ventures in California and the Rocky Mountain Overthrust Belt. Deal describes his success with Windsor as “very gratifying.”

Although Ray Holifield’s clients still have the best records of all, Holifield no longer has a monopoly on success in the Austin chalk. Most of the operators in the play are now using seismic to pick their drilling locations, and several other geologists have come up with what appear to be effective interpretation techniques of their own.

Next to Holloway, Williams, and Deal, the most successful operator in the field thus far is Thomas Coffman of Austin, who has produced roughly $100 million worth of energy from the Giddings area, or just about as much as Deal. Several other companies and individuals, among them Champlin Exploration and Keith Graham, have also done well in the Austin chalk, though not on a par with the top four. Clayton Williams, who had ten wells drilling and had announced 140 prospective locations by late summer, 1980, is probably the most active of the new operators, but whether or not he will make another big killing is still open to question. By the end of the year Williams had produced roughly half a million barrels of oil from the field, only a fraction of the production of companies like Humble and U.S. According to Railroad Commission figures, the average production for all wells in the Austin chalk is 88 barrels of oil and 200,000 cubic feet of gas a day, which is fair but not earthshaking and demonstrates that not everyone in the field is getting rich quickly.

Chuck Alcorn, the man whose well kicked off the Giddings boom, has made a fortune from his discovery, but only a relatively small one. As of the end of 1980 his company had produced a little more than 800,000 barrels of oil from the Giddings area. Roughly two thirds of Alcorn’s production has come from the No. 1 City of Giddings, which no has a cumulative production of 540,000 barrels since 1973 and is still sending up about 20 barrels a day. Even at an average price of only $10 a barrel, the total gross from the No. 1 City of Giddings alone is $5.5 million. By virtue of his various farm-out agreements Alcorn also claims a part-interest in one hundred other wells in the Giddings field and is planning more Austin chalk ventures in the near future.

In the meantime, he has moved into a magnificent mansion on 35 acres near the Victoria County Club and flies about his business in one of two private planes. But Alcorn’s success hardly compares to the hundreds of millions made by the operators who followed him into the Giddings area. Alcorn admits, “I made the conservative choice in farming out my leases to Houston Oil & Minerals back in the beginning. I kind of wish I hadn’t now.” But this he says with the benefit of twenty-twenty hindsight. Through the farm-out agreement, Alcorn has been able to profit very nicely from the field with a minimum of risk. “I haven’t gotten wildly rich like some of those other guys,” he says, “but it’s been the biggest thing in my oil field career.”

The same holds true for Ray Holifield. Besides making hundreds of millions for his clients, he has also done pretty well for himself. With a 2.5 per cent override on every well his clients have drilled in the field, he has grossed an estimated $10 to $12 million from the Austin chalk boom in the last four years. While he was still in the employ of La Rue, Moore & Schafer, Holifield had to give 75 per cent of his override money to the firm. In March 1979 he went into business for himself. He now operates his own geological consulting firm, Ray Holifield & Associates, in North Dallas and has built a large house for his family. But he still works fourteen- and sixteen-hour days seven days a week and pays regular visits to the Giddings field. Although he no longer has holes in his shoes, he remains modest and unassuming and, predictably, secretive about the seismic method that has served his clients so well. The most notable change in his personal appearance is the addition of a diamond-studded Rolex watch, which he wears primarily because it was given to him by Max Williams. Though not a publicity seeker, Holifield has been written up in the business pages of newspapers across the state as the “genius,” the “artist,” and the “magician” of the Austin chalk. But the accolade of which he may be proudest is inscribed on a small plaque some Humble employees have hung outside their new two-story brick office in Giddings: “The House That Holifield Built.”

The Last Boom?