The impulse to make lists is probably as old as language itself. But sometimes the debate that goes into the selections is as much fun as the list itself.

This month we invited five experts (a critic, an academic, two screenwriters, and a theater owner/festival director) to help us determine the ten greatest Texas movies ever. The rules were simple: no documentaries or made-for-TV movies and the list had to be final before anyone could go home. Our panelists were told to bring their own personal top ten as a starting point, and then the culling began. The final list then became the basis for a touring festival, put on in partnership with the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema. That’s right, from June 3 to July 1 you can watch all these movies, either at the location where they were filmed or in a special thematic setting (the full schedule can be found here). And now, the best Texas movies are . . .

The Panel

JOHN BLOOM is a film critic, author, television host, and syndicated columnist who writes and performs under the name Joe Bob Briggs. He is from Dallas.

KYLE KILLEN is a screenwriter and producer whose credits include the television drama Lone Star and the movie The Beaver. He grew up in Burleson.

TIM LEAGUE is the founder and CEO of the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema and the co-founder of Fantastic Fest, an annual fantasy, horror, and genre film festival in Austin.

ANNE RAPP is a screenwriter whose credits include Cookie’s Fortune and Dr. T and the Women. She grew up outside Estelline.

CHARLES RAMIREZ BERG is an author and a professor of film studies at the University of Texas at Austin. He is from El Paso.

CHRISTOPHER KELLY is a writer-at-large for texas monthly and the film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

•••••

CHRISTOPHER KELLY: So let’s just begin with the big question: What makes a Texas movie? What is the definition of a great Texas movie?

JOHN BLOOM: The great Texas movies, in my opinion, are about evil and sinners and darkness. Most of them are about West Texas. There’s a few about South Texas, but most of them are about West Texas. Even the ones that are about East Texas, they make them look like they’re in West Texas. And I’m not talking so much about geography as I am about the misfit, borderline criminal, sometimes borderline psychopath, that seems to thrive in West Texas. Red River, that’s John Wayne’s most psychopathic role. The Coen brothers got it exactly right when they made Blood Simple. The Coens, you know, they’re not from Texas. They’re making their first movie; they say, “We want to set a movie in Texas.” Why? Because evil thrives in Texas.

KELLY: What about you, Kyle? What do you think makes a film a Texas movie?

KYLE KILLEN: If it uses Texas as a character. But Texas can play a lot of different roles, the same way actors can do different things. There are good Texas-filmed movies that don’t feel like they have Texas as a character, that could have happened anywhere else in the nation, and those aren’t really Texas movies.

ANNE RAPP: Well, I thought about that all week, and the only thing I could come up with is that simple thing that if you go into a movie and come out and feel like you spent two hours in Texas, that’s a Texas movie to me. If you feel like you just spent two hours in our universe—that’s the parameters I use.

TIM LEAGUE: I started going through my list and looking at Texas archetypes, and I sort of second-guessed Dazed and Confused. It’s a phenomenal film, but what’s powerful about it is that it feels universal. There are very few elements that are distinctly Texan. So I’ve already pulled that one out, because it doesn’t reek of Texas. It reeks of adolescence. Whereas Friday Night Lights—that reeks of Texas. That’s a distinctly Texas story.

BLOOM: Jean Renoir made a movie in 1945 called The Southerner. It was based on a novel [Hold Autumn in Your Hand] by George Sessions Perry, who was from Rockdale. It’s a movie about blackland farming, and it’s a very good movie. So, in my opinion, Jean Renoir is more of a Texas filmmaker than Richard Linklater. But also, from a chauvinistic point of view, I think Dazed and Confused, which is our coming-of-age high school graduation movie, is inferior to American Graffiti. And I don’t like being second-best to California.

CHARLES RAMÍREZ BERG: I tried the commutation test, where you take a movie and set it someplace else, and I agree. I think Dazed and Confused could have been Kansas City. Whereas I think Giant, that’s Texas. You have ranching, oil, and discrimination against Mexican Americans. That could only happen in Texas. Whether it was shot in Burbank or not.

BLOOM: Even though it was written by a Yankee.

RAMÍREZ BERG: I would say Slacker is more of a Texas movie than Dazed and Confused, because that could have been made only in Austin. That’s an Austin, Texas, story.

KELLY: But not one of you mentioned Slacker in your preliminary lists. Let’s table Dazed and Confused for a bit and come back to it.

LEAGUE: I want to throw one more monkey wrench into the criteria. The Searchers is a bit of a mess as a movie, but it’s been so influential. And there are certain movies like this that have resonance after the fact. I wouldn’t say The Searchers is one of my personal ten favorite movies, but it’s certainly one of the most important movies of the modern era. Does that factor into the top ten?

RAMÍREZ BERG: I voted for it, and I think it is a Texas story, even if it was shot in Monument Valley, because it’s set in Texas, it’s about the Comanches, and it’s about racism. And that’s part of the Texas story. That’s the story of Giant.

BLOOM: The Searchers is a Texas story, an Oklahoma story, a New Mexico story—it ranges all over the Southwest. But it starts in Texas, with that line of houses, those white people trying to push the frontier, those lone-wolf families out there on the edge of civilization out of sheer stubbornness.

KILLEN: That’s a Texas quality.

BLOOM: It’s the greatest movie about Texas stubbornness. There is no reason for that family to stay there, waiting for the next Indian attack. And the other thing is, why would you search? John Wayne knows that by the time he finds this girl she will have become a Comanche. So why would you spend eight years searching? That’s another Texas trick: Men never quit. Even after there’s no longer any point.

RAMÍREZ BERG: It’s because he wants to save her. And then he wants to kill her to get her out of the family, out of shame.

BLOOM: What about Rio Bravo?

LEAGUE: It’s one of my favorite John Wayne performances.

BLOOM: You like Ricky Nelson as a cowboy?

LEAGUE: I do like Ricky Nelson in that movie. I like everybody. I like Dean Martin in that movie. But I don’t think it’s important. It’s a popcorn movie.

RAPP: What about Red River?

LEAGUE: It’s a little too ham-handed. The complexity of issues in The Searchers is more interesting.

BLOOM: But John Wayne is a meaner son of a bitch in Red River. Even Walter Brennan doesn’t like him, and Walter Brennan likes everybody. But I get the impression that if a western makes this list, it’s probably only going to be one western. There have been hundreds of ’em, and we didn’t have that many on our lists.

KELLY: Maybe there’s not a truly defining Texas western.

BLOOM: Red River is probably as close as you get.

RAPP: I would say Red River.

RAMÍREZ BERG: It’s Hollywood’s version of the founding of King Ranch. And Hollywood’s version of the Chisholm Trail and the first cattle drive. I mean, that’s pretty Texan.

BLOOM: Plus he kills a lot of people.

KELLY: So Dazed and Confused is probably out, and Red River is probably in. But let’s come back to your lists for a second. We had two movies that everyone agreed on: The Last Picture Show and Hud.

RAPP: Last Picture Show is a documentary of the first twenty years of my life. I watched it again last night, and I’d forgotten just how authentic it is. I know that dusty, confining town where everybody only talks about football. But what I loved about it when I saw it again was the women. Women have all the power in that movie in some kind of odd way. And that’s the way it is sometimes in those small towns. I grew up in a town that was three hundred people in the Texas Panhandle, and we were a hundred miles from Amarillo, which was the closest town of any size, and I felt it all, sitting through that movie again.

LEAGUE: It’s also another example of people from the outside getting it. Peter Bogdanovich couldn’t be less Texan.

BLOOM: If we were to make this harder and say we have to pick the best movie based on a Larry McMurtry story, even though I think I should vote for Last Picture Show, emotionally I want to vote for Hud. Hud to me captures the loneliness and seething undercurrent of Texas lives.

KELLY: Fortunately, you don’t. Does anyone have objections to both of those movies being on the list? [No objections raised.]

RAMÍREZ BERG: The same is true for Giant, no?

LEAGUE: It’s a deeply flawed movie, but if we’re here to talk about Texas movies, then Giant has to be on the list. I mean, subject material, quintessential Texan characters, independent spirit . . .

RAMÍREZ BERG: The fight in Sarge’s diner. That’s iconic.

BLOOM: Actually, I don’t like the end of Giant. I like everything else about the movie, but I don’t like Rock Hudson coldcocking the guy at the diner, because I think the subtext there is “Finally Philadelphia manners have overcome Texas culture.”

RAMÍREZ BERG: My mother, who is Mexican, took me to see that movie when I was twelve. She had seen it before, and it was being rereleased. It was a Sunday, so we go to 11:30 mass, then we go eat lunch, and then we go to the State Theater in downtown El Paso to watch Giant. Right before the fight in Sarge’s diner she leans over and says, “Pay attention to this.” She was trying to tell me something about discrimination and how it feels to be a Mexican in Texas. She was telling me a lot by just telling me to pay attention to this scene, and so I would say put it on the list. It’s probably number one for me on the list.

BLOOM: I think it’s like, you know how everyone hates the second half of Lawrence of Arabia? Well, once they get to the Shamrock Hotel, Giant is not as interesting as the part where they are out on the ranch. But put it on the list.

KELLY: All right. We have four votes for Bonnie and Clyde.

RAMÍREZ BERG: I was the one who didn’t vote for it. It doesn’t scream out, “This is a Texas movie.” It could be Missouri or Oklahoma. I know a lot of it historically is set in Texas, but it feels more like a Midwestern story than a Texas story.

BLOOM: That’s because it’s North Texas, the most neglected part. You know, northeast Texas is not interesting visually to begin with. But the reason it lends itself to a Depression-era drama is that people abandon those little towns, and so they have those old buildings, and a film crew can go in and dress them up and shoot scenes there.

KILLEN: I would argue that the story is born out of the same thing that led to Last Picture Show: Texas is so big, and you can be isolated, and there’s a hopelessness and an ennui that takes place that leads to something like going on a Bonnie-and-Clyde-style rampage. That’s what Texas does to human beings.

BLOOM: The reason I think it ought to be on the list is that it’s a Dallas movie, Dallas being the least Texan of all Texas cities. The problem is, Warren Beatty doesn’t read Texan. Also, it may be one of the only times that a Texas Ranger has been portrayed in a negative way. Texas Rangers do really well in movies. They’re always portrayed in a positive light, even if they’re murderers. In Riders of the Purple Sage there’s a Mormon killer, but he’s a Mormon killer with a heart of gold.

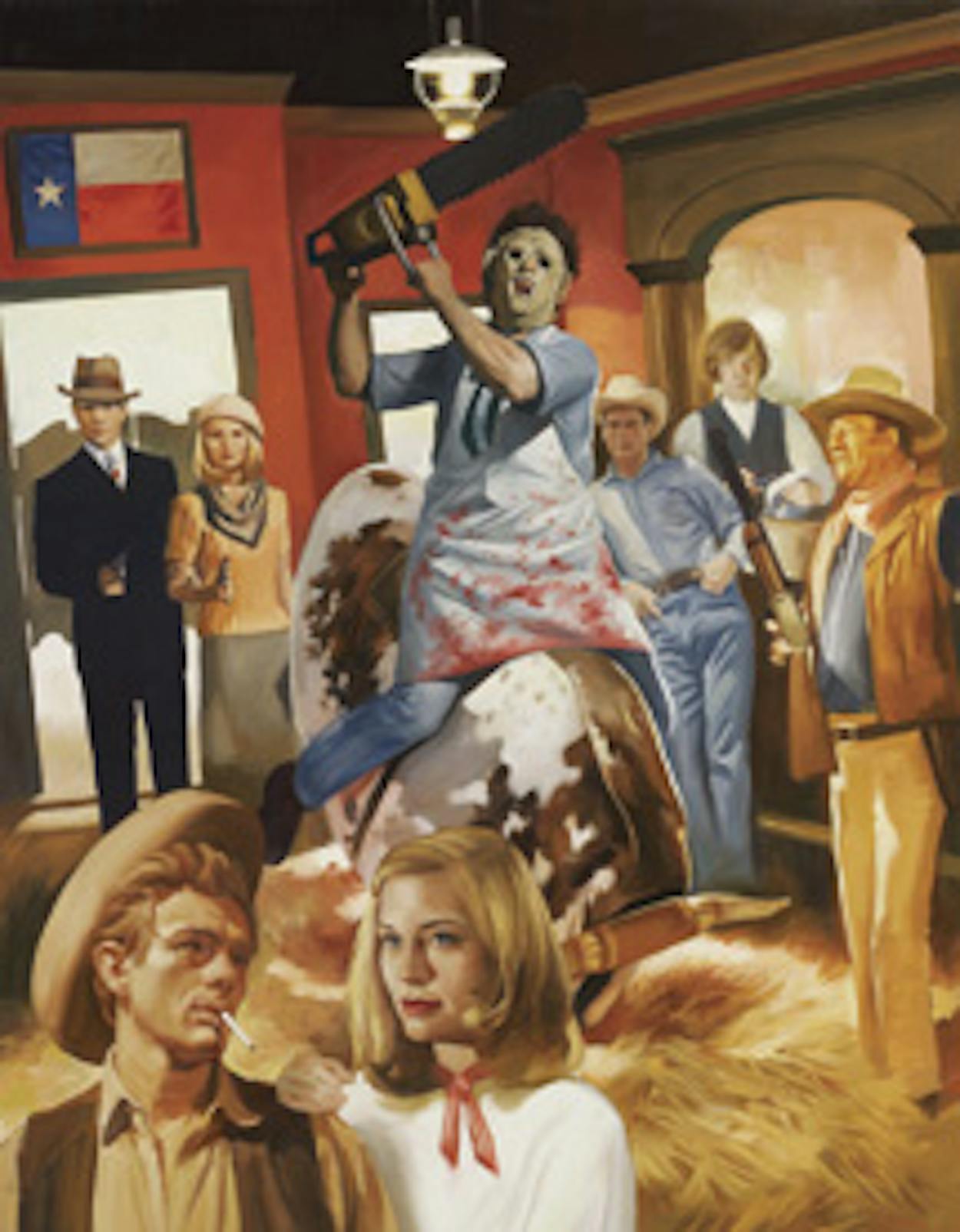

KELLY: So can I put a check mark next to Bonnie and Clyde and get us up to four? [All agree.] All right. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Make your case.

LEAGUE: A lot of people have argued this is the most influential horror film of all time, and at the same time, there are Texas themes that resonate through it. There is the death of quintessential Texas industries, of the cattle industry falling apart, and that’s what drove this family to cannibalism. There is this lurking darkness in rural Texas. The movie was made by Texans in Texas; the word “Texas” is in the title . . .

BLOOM: If you read any of the outrage surrounding the release of this movie—especially from the eminent writers and New York literati who attacked it—of the three words in the title, the one they found most offensive was not “chainsaw” or “massacre.” They believed that the movie was a justification of a violent outlaw state. I don’t know of any other movie that remains on banned lists for more than thirty years after its making. It’s the ultimate outlaw movie. And it is a Texas movie. What makes it Texas horror as opposed to just any horror is that it’s done with comedy—the fact that when they finally get to the slaughter room they have to hold up Grandpa’s arm to hold the hammer and the hammer keeps falling out of his hand. They’re scary but they’re also funny.

RAPP: But, you know, I put it next to Blood Simple or No Country for Old Men, and there’s no comparison. Blood Simple—that film is almost flawless.

BLOOM: I like Blood Simple too. But it’s very cinematic. It is based on images and ideas of Texas from film history and from popular-culture history more than it is based on real people living in Texas and whatever they are here to say.

RAMíREZ BERG: Me too. I tend to agree with that. It has that quality of early films, which is that it’s kind of show-offy.

LEAGUE: It’s like they’ve taken the concept of the film noir story, which is an L.A. phenomenon, and inserted some Texan characters into it. I mean, between No Country for Old Men or Blood Simple, I’d pick No Country.

BLOOM: I’ve seen so many scary movies that there are very few movies that can scare me. No Country scared the crap out of me.

RAPP: What’s the scariest movie you ever saw?

BLOOM: That’s one of the scariest. No Country for Old Men. It’s one of the scariest.

RAMíREZ BERG: That movie is set in El Paso in 1980, and I was living there at the time, and so was Cormac McCarthy, who wrote the novel. And it captures West Texas. The crazy thing about that drug shoot-out was that it was just like that. I remember one time in my neighborhood, right in the middle of the day, there were these two guys running through a park, shooting at one another. And that was all drugs. It was just that crazy. So I thought they just nailed that. They completely got that.

KELLY: Okay, it sounds like we all agree on that. Which gets us to five. So now it gets harder. Who wants to make the case for Tender Mercies?

LEAGUE: I thought it was beautiful and spartan. You understand so much of the characters with so few syllables, which is also a very Texan trait. You know, you compare that to Crazy Heart—good Lord, there is no comparison.

RAMíREZ BERG: Yeah, not even close.

LEAGUE: It delves into country music. It has a very classic couple of Texas characters. It involves the barren Texas small-town landscape. Also, Robert Duvall never apologizes for obviously being a bad, drunk husband.

RAPP: And he explains it in the end: “I never trust happiness.” One of the top five scenes ever in movies. “I don’t trust happiness.”

KILLEN: I don’t know, something about country music doesn’t actually feel Texas to me. It feels Nashville. And the whole vibe in Tender Mercies is sort of “Texan for profit.”

LEAGUE: It could be a Nashville movie too.

RAPP: Well, but think about that movie, though. One of the most brilliant things about Tender Mercies is the Tess Harper character, and the movie is set in her world, which is really Texas. Country music is brought into that world by Duvall’s character, but the most-genius parts of that movie have to do with her, her ability to listen to him. Scene after scene after scene—that woman is the best listener I’ve ever seen.

BLOOM: And thirty years later she’s still listening, to Tommy Lee Jones in No Country for Old Men. I agree with you. And having grown up in a little Baptist church in that type of atmosphere, I can tell you that [director] Bruce Beresford got that so right. That little church where he is baptized. I was floored by that. I’m sure that if you’ve never been in one of those Baptist churches, it was interesting but not compelling. To me it was like, “My God! How did they get every single emotional detail of that experience all in that one little scene?” And it works virtually without dialogue. I think it’s the greatest screenplay Horton Foote ever wrote, and I’m not a Horton Foote fan. I’m like the actors in New York who say, “Well, he’s written fifty plays, but we’re still waiting for the first plot twist.” That’s his reputation, because he is what you call a “slice of life” writer. But in Tender Mercies, he just got it so perfectly right. It’s one of the few things he wrote directly for the screen. And for some reason, the Australian [Beresford] understood once again.

RAPP: The Aussies always get Texas. And the Brits never do.

BLOOM: The Brits just want big hats and guns, right?

RAMíREZ BERG: It could be they have the same vistas, you know, they have the wide-open spaces . . .

RAPP: There are so many scenes in Tender Mercies where there are no cuts. That scene in the garden—it’s just one shot. The camera kind of drifts around, and you see this lonely landscape they live in. And Duvall makes the most powerful speech. And then her listening, and that body language. You know what, though, the studio went ballistic over that. “Where’s the coverage in the scene?” they said. And [Beresford] told them, “Well, you don’t want close-ups in this scene.” And he was right. It’s beautiful the way it is.

LEAGUE: It’s a very Texas courtship.

BLOOM: Also Robert Duvall had the Texas accent exactly correct. Usually they’re very lazy about putting a Mississippi accent in a Texas movie, or any generic Southern accent. He’s perfect on the Texas accent. I know he worked really hard on it. And he has been doing it ever since. He did it in Lonesome Dove, The Apostle.

KELLY: Okay, it’s in. Let’s do some eliminations. We have six. Before we go on, let’s deal with Urban Cowboy. Tim?

LEAGUE: Well, it captures a very specific time and place: Houston, Texas, during the oil boom. And it captures that fad of “fake Texas.” It’s actually a pretty special movie in a way, but it’s not a very good movie from any sort of cinematic standards. Nobody could make that case. It’s just a cheap, hackneyed rip-off of Saturday Night Fever that exploits John Travolta, whose performance is one of the worst depictions of an actual Texan ever. You don’t believe he’s Texan at all. But there was that ripple effect. Urban Cowboy was chic, and Gilley’s was an entity.

BLOOM: I don’t even think it was a good depiction of the fake Texas fad. It wasn’t even a good mechanical bull.

RAPP: It was a terrible movie.

KELLY: What else?

LEAGUE: Can we knock off Lone Star?

KILLEN: Actually Lone Star would be my argument against The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada. I thought it was actually better than Three Burials. It covers the same part of Texas, treads in the same territory, and I thought it was actually great.

RAMíREZ BERG: You know, and there’s an example of a guy from New Jersey who came down, spent three weeks on the border—and I thought he got it.

RAPP: I don’t know. I thought Three Burials was so authentic. I loved the way it was told. The landscape—it doesn’t get any more Texas than that. But you’ve got to love the story, you’ve got to love the experience, and I’m the only one who did. I think I’m the only one fighting for Three Burials.

KELLY: Does that mean Lone Star is off? [All agree.] And Three Burials is off? [All agree.] That leaves us with seven titles for four slots. The seven are Dazed and Confused, Red River, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Blood Simple, The Searchers, The Apostle, and Friday Night Lights. Just write down your four out of the seven and let’s see how close we are and where the outliers are. [The guests vote.] Okay, from this I can discern that Dazed and Confused is out. It had only one vote.

LEAGUE: And I was on the fence on it.

RAMíREZ BERG: Wow, I’m actually surprised about that.

LEAGUE: It’s tough. I had Friday Night Lights versus Dazed and Confused, and it’s a really hard thing because it’s the same subject material. But I went on the Texas nature of it.

KELLY: Looks like we’re keeping Red River and The Searchers. So now we have eight. And we have four votes on Blood Simple. So that leaves Chainsaw, Friday Night Lights, and The Apostle.

BLOOM: Texas Chainsaw should be on the list.

RAPP: Of those three, hands-down the Texas movie is Friday Night Lights.

BLOOM: I don’t think so. I think Texas Chainsaw Massacre is very Texan—in its story, the creators, the funding, the history of the movie itself, the effect on the state.

RAPP: Well, I think every movie we’re talking about is a Texas movie. It’s a matter of what’s the best dadgum movie.

LEAGUE: I can’t in conscience let go of Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

KILLEN: I would offer up Blood Simple to the chopping block to put Friday Night Lights in.

RAPP: We cannot lose Blood Simple. I’ll do anything. It’s better than half of the movies we’ve chosen. So I’ll go with Chainsaw, and the only thing left behind on the table is Friday Night Lights.

KELLY: So Chainsaw? [All agree.] And that’s our ten films: The Last Picture Show, Hud, Bonnie and Clyde, Giant, No Country for Old Men, Tender Mercies, Blood Simple, Red River, The Searchers, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

BLOOM: That’s the canon.

•••••

And now, the Alamo Drafthouse Presents . . .

The Texas Monthly Rolling Roadshow

Starting June 3, the Alamo Drafthouse and TEXAS MONTHLY will be showing all ten of these films in unique, location-specific settings all over Texas. For more information, please visit texasmonthly.com/texasfilms or drafthouse.com/texasfilms.