In a day and age when slim-hipped, long-legged college girls with ponytails regard it as their God-given right (as well they should) to run 400-meter hurdles and elbow their way into the paint, it’s tough to imagine what an unusual figure Mildred Ella “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias cut. Babe, who grew up poor in Beaumont, was the greatest female American athlete of the first half of the twentieth century and one of the century’s greatest athletes, period. She was the first woman to play in the Professional Golfers’ Association; a founder of the LPGA; an All-American basketball player; a winner of gold medals in track and field in the 1932 Olympics; and a notable boxer, bowler, diver, and baseball player as well. In 1953, while still competing, she was diagnosed with rectal cancer. At a time when cancer was regarded as something shameful, Babe went public with her struggle, raising money for medical research and offering hope to patients all over the world. Amazingly, a year after her colostomy, she won her third U.S. Women’s Open. A year later, she was dead at the age of 45.

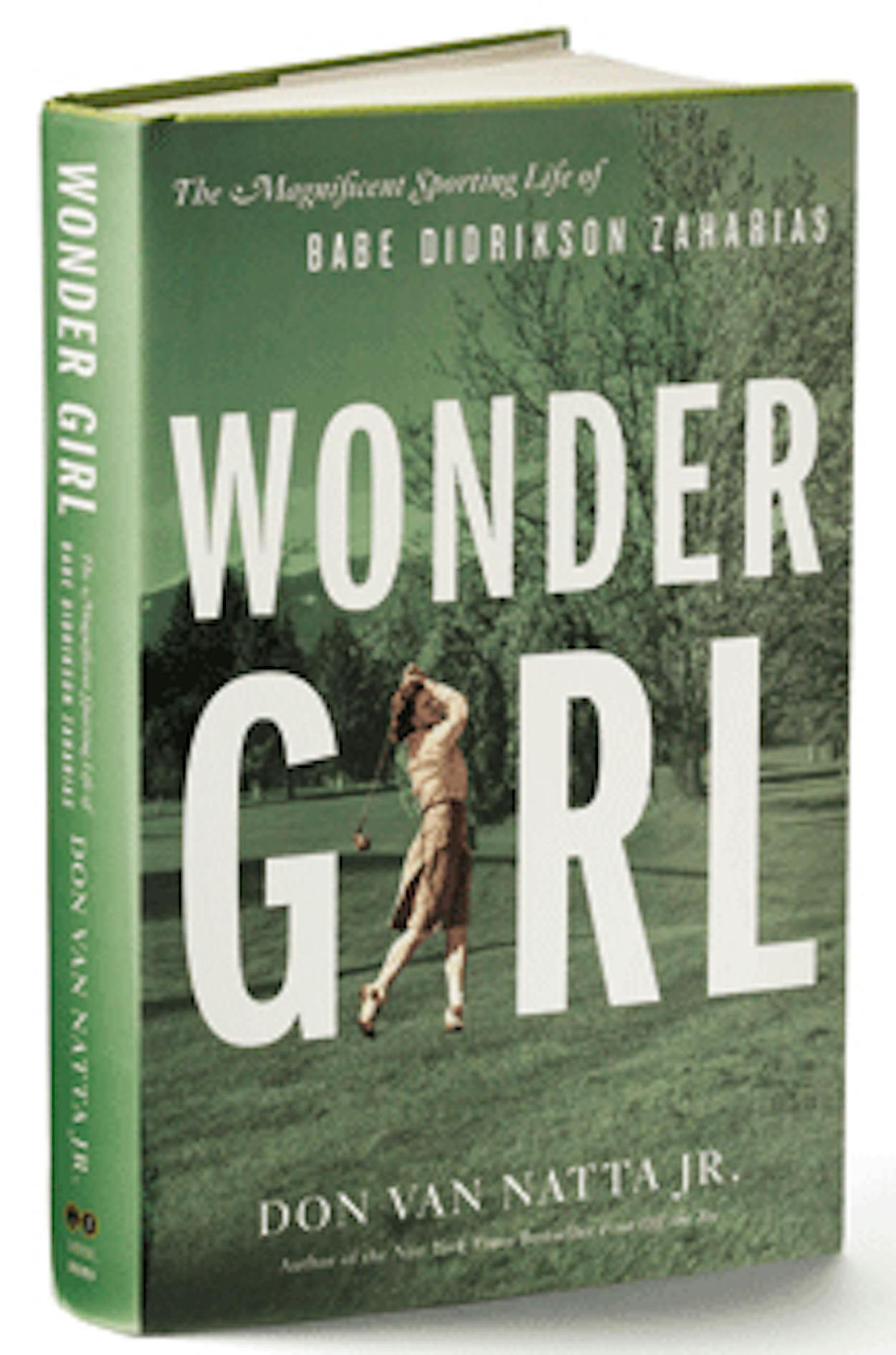

Babe would have turned 100 this year, the presumed peg for New York Times reporter Don Van Natta Jr.’s Wonder Girl: The Magnificent Sporting Life of Babe Didrikson Zaharias (Little, Brown; $27.99). Van Natta is at least the fourth writer to take on Babe since she dictated her story to Harry Paxton in 1955, and he does an excellent job of explaining how this singular figure came to be. Babe’s parents, Ole and Hannah Didriksen, a pair of Norwegian immigrants, raised seven children in a shotgun house near the Magnolia Oil refineries. (Babe later changed the spelling of her surname to Didrikson, claiming she didn’t want people to think her family was Swedish. I’m flattered that she thought Texans could tell the difference. Which one has the fjords?) Van Natta gives us the ache of a tomboy childhood lived on the edge of poverty without turning the tale into a Horatio Alger story. Babe, in this telling, was a girl who, from her earliest years, was running and jumping and getting into trouble at pretty much every opportunity.

It wasn’t easy being an athletic girl in those days. When I was growing up in East Texas in the late fifties—in the Piney Woods, not the Gulf Coast—a young man from the poorest neighborhood who became the star of the gridiron gained access to the bank president’s daughter and perhaps a college scholarship, which guaranteed him a place in the middle class. Girls had no such motivation, and if their athleticism trumped their femininity, they were regarded as freaks (unless they looked particularly smashing in tennis whites). Girls who canoed the Guadalupe at summer camp worked all year to get rid of those rippling back muscles.

Perhaps because femininity was never an option for the mannish-looking Babe, she never let the gender expectations of the time slow her down. She wanted to escape her family’s poverty, but she was a terrible student; her athletic ability and her intense competitiveness were all she had to draw on. Babe’s grave marker, in Beaumont, displays an open book etched with the words “It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you played the game.” Babe never said that. Her motto was “I don’t see any point in playing the game if you don’t win.” According to Van Natta, she breezed into country club locker rooms before tournaments, asking, “Now who’s gonna finish second?” Van Natta doesn’t flinch from portraying Babe’s spotlight hugging and poor sportsmanship, or the coarseness that initially kept her from being embraced by the country club ladies who then made up women’s golf.

At such moments, Wonder Girl makes clear that this isn’t only a story of a woman breaking down gender barriers but of a working gal breaking down class barriers. Babe’s blue-collar background (she thought pork ’n’ beans and strawberry soda made a fine meal) and her muscular style of play did not endear her to Texas high society. Van Natta includes an anecdote about one of the Lone Star State’s finest amateur golfers, Dallas’s fashionable Peggy Chandler, blanching at the thought of Babe’s competing at Houston’s River Oaks Country Club. “We really don’t need any truck drivers’ daughters in our tournament,” Chandler said. (Ole Didriksen was actually a carpenter.)

This sort of snobbery was doubtless exacerbated by Babe’s androgyny; her close-cropped hair and broad shoulders made her appear shockingly masculine. Mentioning Babe Zaharias to my male contemporaries always brings a grumble of “Well, you just can’t be sure she was really a woman.” (When I was twelve years old, I took one look at a picture of her and decided I’d take up swimming rather than golf.) Presumably to deflect such speculation, she made a show of emulating the era’s happy homemakers, planting roses in her garden, decorating her house, wearing makeup, and cooking meatballs.

There was at the time, no doubt, a lot of hushed innuendo about Babe’s sexuality, but it could hardly have been discussed publicly. Today, no one shies away from such topics, though Van Natta refuses to speculate beyond where the evidence leads. He does an engaging job of describing Babe’s marriage to George Zaharias, a wrestler, promoter, and for a while, her manager. Zaharias was a character right out of Damon Runyon. Like Babe, he was a pushy kid from an immigrant family who did everything he could to escape the life he’d been born into. (I didn’t know until reading Wonder Girl that the Katharine Hepburn–Spencer Tracy movie Pat and Mike is a thinly veiled account of the Zaharias marriage.)

The union was, for many years, a marriage in name only, and much has been made of Babe’s relationship in the last years of her life with Betty Dodd, a golfer from San Antonio young enough to be her daughter. Dodd quickly became her constant companion, even as Babe was dying, and Zaharias resented her presence. (Babe likely realized how useless Zaharias—indeed most men of the time—would have been as a bedside companion in a hospital.) One of Babe’s previous biographers, Susan E. Cayleff, all but stated that Babe and Dodd were lovers, but Van Natta reports that “the women on the tour who were closest to Babe remain to this day convinced that she was not a lesbian, mainly because of her constant chatter about men, even in the years leading up to her death.” Obviously, this may have been an act; even a semi-private admission of lesbianism could have derailed Babe’s career. But that’s just conjecture, which Van Natta, wisely, doesn’t engage in. “I don’t pretend to know what happened inside Babe’s bedroom and have not found conclusive evidence either way,” he writes.

Few of today’s celebrity biographers are quite so modest in their assumptions. But Van Natta doesn’t have a predatory bone in his body; Wonder Girl is the life story that Babe, who paved the way for countless modern-day golfers and track stars who have never heard of her, deserves.

Textra credit: What else we’re reading this month

Pacific Heights, Paul Harper (Henry Holt, $25). Austin thriller writer David Lindsey returns after a seven-year absence with the pseudonymous first installment of a new series.

Breaking Their Will, Janet Heimlich (Prometheus, $20). Austin journalist looks at the long-taboo topic of “religious child maltreatment” across a variety of faiths.

The Homecoming of Samuel Lake, Jenny Wingfield (Random House, $25). Texas screenwriter’s first novel, about a family dealing with upheavals in fifties Arkansas.