This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

To reach Energy Street in Alice, you drive east on Texas Highway 44 until you come to a small, modern-looking industrial park near the airport. During the oil boom, Alice was the center of the oil-field service industry for the South Texas brush country. The dizzying spirit of the boom is still evident in the buildings, which are made of brick instead of prefabricated metal, and in the street names, which, in addition to “Energy,” are “Fortune” and “Progress.”

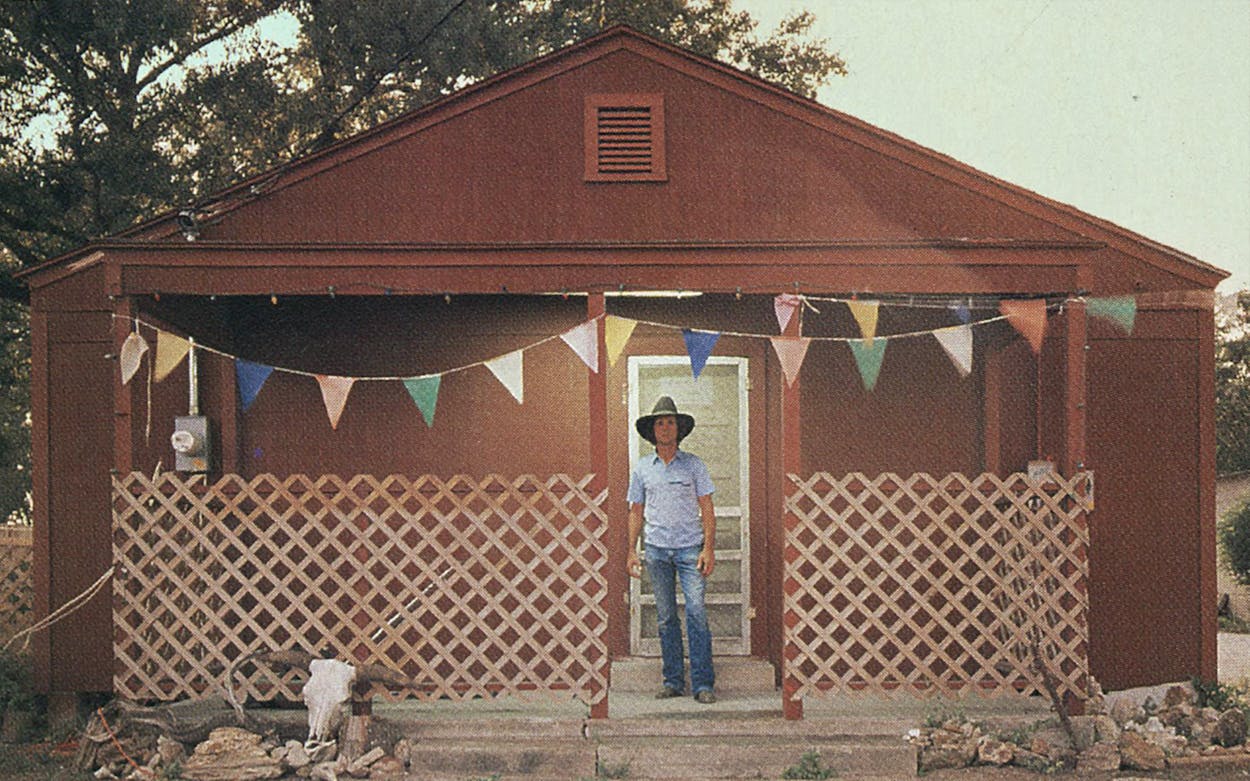

But today the industrial park is depressed, and the attitude of Alice itself is that of a jilted lover. Underemployed workers and the unemployed sit around wooden tables at places like Buck’s Barbecue Shack on U.S. 281 North, nursing frosty mugs of beer and reminiscing about better times, before the price of crude ran away with the Saudis. Buck’s is such a place of solace for oil hands that even the sculpture of a javelina above the refrigerator wears a white hard hat.

“I was fat and sassy during the boom. I just laid back and grossed more than thirty-five hundred dollars in a day without even trying,” says Don Schultz, a mud logger who is nibbling on a chopped-beef sandwich. The baby-faced, blond Schultz explains patiently that a mud logger is the secretary of the drilling rig, keeping records of the drilling rate and looking for signs of the precious presence of oil and gas. Lately Schultz has logged wells not for a day’s wage but on the chance that if oil and gas are found, he will be paid for his services. He gave up his $400-a-month apartment in Houston months ago and now lives out of his trailer. “I logged nine to ten dry holes, so I got zip, zero, nothing. I have actually ended up spending my own money to work,” says Schultz. “Ain’t it crazy?”

Schultz’s buddy, a mud engineer named Wayne Figg, has just driven into Alice from Houston, where he buys mud off the docks at the Houston Ship Channel. Figg hauls it to well sites and trades it not for dollars but for an interest in the wells—if oil is struck. That practice is known as vendor financing, and it is an example of how desperate times are in the oil-field service industry. All over Texas, oil-field services are being provided on speculation, not cash; new wells are being drilled on handshakes.

Everything from cement and pipe to the very sweat off the brow of roughnecks is supplied on nothing more than hope that the well will hit and everyone will be back in the money again. “I participated in eleven wells last year and got only a hundred and eight dollars in cash,” Figg says. “I’ve put these wells in my children’s names. If they hit, my kids are gonna be set for life. If they don’t . . . well, that’s the oil business.” How does he pay day-to-day bills and buy groceries? A nervous smile masks a cold shudder. “I have a wife who works for Neiman-Marcus in Houston. Otherwise, we’d be in the poorhouse.”

Vendor financing is a throwback to the early days in the oil patch. Then, roughnecks worked for a decent wage if the well came in and for room and board if the hole came up dry. A common complaint heard in 1986, when oil was at the humiliatingly low price of $10 a barrel, was how the oil patch had been ruined by bankers and lawyers who needlessly complicated the lives of individualistic oilmen. When Figg talks about his handshake deals, his voice has all the old passion of the wildcatters. The trouble is that the handshake seldom lives up to the vendor’s high expectations. Figg participated in a vendor-financed well that wound up producing 750 barrels a day. “The guys who put the deal together decided they didn’t need to pay for the mud,” recalls Figg. “That particular handshake is now in the courthouse.”

Ask anyone in the service industry about the mood in Alice, and every one of them will give you the same answer: cautiously optimistic. That’s the phrase they have read in the big-city newspapers, and the sound of it coming from their own mouths seems to make them feel better. Yet they seem more cautious than optimistic. The service arm of the industry, even more than the exploration arm, has been changed beyond recognition by the bust. Even after years of shutdowns and layoffs, there are still too many firms chasing too few rigs. Old methods of doing business have disappeared, to be replaced by lowball bidding, bartering, and cutthroat competition.

Every week the Alice Echo prints the Hughes Tool rig count, which oil-field workers watch as carefully as the mother of a feverish child studies mercury in a thermometer. On March 13 the Echo reported that 46 rigs were at work in South Texas, compared with 28 last year. The total number of rigs working in the United States for the week ending March 7 was 978, compared with 766 for the same week in 1987. Those numbers sound good, until you consider that in 1981 more than 4,000 rigs were working in the U.S. “The oil business is coming back,” says Ralph Gomez, the vice president of First City Bank in Alice, “but it’s coming back real slowly.”

Alice, a city of 22,273, has at least a hundred homes for sale in the $100,000 range. “Back in the boom, we had a terrible housing shortage. Back then it seemed like everybody had a swimming pool and drove a Lincoln,” Gomez says longingly. His bank still makes oil and gas loans, but now the loan officers require all energy loans to be backed by collateral other than the promise of reserves.

At the Halliburton laboratory, off U.S. 281 North, six employees dressed in white lab coats are testing the thickening times for cement. In 1981 the lab had sixteen workers. “The experience level of our employees is probably the highest it has ever been,” says Jerry Logan, the assistant division engineer for Halliburton. “If you weed out two thirds of your work force, then the third you’ve got left is pretty able.” Logan has only recently seen the first signs that drilling activity has increased. All of the lab’s consistometers, small machines that look like ice-cream mixers and test cement for down-hole conditions, were whirring in the background. “Sounds real pretty, doesn’t it?” Logan says.

The ailments of the service industry appear in symptoms unrelated to oil. One Alice home in eight was burglarized last year, and citizens are holding town meetings about the crime spree. The total value of property in Jim Wells County has declined for the last two years. In 1986 it was $950 million, and it fell to $821 million last year, far below the boom-time high of $1.4 billion in 1982.

The bell cows of the oil-service industry are drilling contractors. They lead prices down in a bust and back up in a boom. Since oil prices collapsed two years ago, Alice drilling contractors have been underbidding each other in desperate competition for work. They have lowered their break-even point with layoffs, cost trimming, and corner cutting.

At 68, Lucien Flournoy, a major political power broker in South Texas, still comes into his drilling office at three o’clock every afternoon to look over bids on drilling new wells. “We’re fighting a battle that’s not worth fighting,” he grumbles. “The truth is, a barrel of oil has never been worth less than 20 dollars and never been worth more than 25 dollars. Until it gets back up to 20 dollars, we’re just twiddling our thumbs down here.” Even at the $15 level, however, Flournoy and other drilling contractors are seeing a few more rigs go to work.

In good times, drilling contractors billed customers by the day or by the foot. In the bottom of the bust, Flournoy and other drillers were locked into fixed-price bids, and if something went wrong, they had to absorb any extra cost. Perhaps the best sign of hope in Alice is that a few drilling jobs are again being bid by the day or the foot.

Burt Harkins, whose family-owned company has been drilling wells in South Texas for 43 years, believes the oil industry in Texas hit bottom in April 1987 and has been inching forward since then. This year Harkins is working all thirteen of his rigs; a year ago he had only one rig in operation.

The service companies that survived the bust, like the oilmen who survived, are those that didn’t bet everything on the boom. Instead of going into debt, Harkins and Flournoy each laid back profits in the good years.

Harkins’ company took 32 years to go from a four-rig operation to his high number of fourteen rigs in 1977. By contrast, Magee-Poole Drilling, another drilling contractor, set up shop close to Harkins and Company in the early eighties and borrowed enough money to buy fourteen rigs in eighteen months. When prices fell, Magee-Poole went out of business. Today some of those rigs that were bought in 1981 for $4.5 million on borrowed money are sitting in the contractor’s abandoned yard. Rigs that once sold for $4.5 million are now bringing about $365,000, but even that figure is up from $250,000 in 1986. “Still, it doesn’t do a contractor any good to buy new rigs if operators aren’t ready to put up the money to drill,” Harkins says.

Because equipment is so cheap, the rental business is among the hardest-hit service industries. In 1981 about twenty people worked at an oil-field rental company on U.S. 281 North; today three employees handle the whole shop—and that’s two more than were needed a year ago. Marvin Diebel, who has managed the shop for seventeen years, has no intention of simply giving up and finding another trade. “I can stand the heat one day longer than the Saudis,” Diebel says proudly. Harkins puts the same thing another way: “People who work in the oil fields are like mother coyotes. In times of scarcity, a mother coyote will eat frogs or snakes or whatever it takes to draw her next breath. You can’t kill a mother coyote, and you can’t kill us.”

- More About:

- Energy

- Business

- TM Classics