My first morning at the Holiday Inn Express in Pearsall, an hour or so south of San Antonio, I left my room just before six o’clock and rode the elevator down from the third floor. It was a Monday, and I shared the descent with four fellows carrying lunch boxes, hard hats clipped to their belts. They were strapping young men, and their red fire-retardant jumpsuits, with “Halliburton” stenciled across the back, made them appear intimidatingly huge, and me feel almost ancient.

We followed boot tracks of fracking sand and drilling mud down the hall to the breakfast room, where the men lined up at the buffet for plates piled with biscuits and sausage. I got coffee and went outside to catch the sunrise. As I watched the eighteen-wheelers roar by on I-35, headed south to the Eagle Ford Shale or on to Laredo, I thought about how normally, at home in Fredericksburg, I would be out back with my wife and cat, waiting for a pair of Cooper’s hawks to rise noisily from their nest across Barons Creek.

At eight o’clock sharp I wandered back to the breakfast room and took a seat, nodding to the seven other landmen who drifted in. At the front of the room a folding table held stacks of legal-size folders. Behind the table stood our new boss, Karl, a middle-aged fellow with an air of indifference about him who had driven in from Houston. He tapped a pencil on a yellow pad. We got quiet.

“You landmen are independent contractors,” he said. “You are paid when you work. If you’re sick and can’t work, you don’t get paid. If your car breaks down and you can’t work, you don’t get paid. You are paid for working. Is that clear?” He paused and looked around.

“Don’t text me. If you text me, you’re fired.” Then Karl almost smiled. “No, I’m easier than I used to be. But don’t text me. Not ever.”

He introduced Larry, our crew chief, who appeared to be in his sixties. Larry leaned against a wall, fingering an unlit cigarette. Then Karl handed out files for tracts of land in La Salle County, around Cotulla, in the heart of the Eagle Ford Shale play. The land was thirty miles south, but we would commute from Pearsall because the Holiday Inn Express in Cotulla charged $250 a night.

Landman work—researching mineral ownership for oil companies—was something I had learned as a young man, a skill to fall back on when I needed extra money. I’d last resorted to it some thirty years ago. In the decades since, I’d worked primarily as a writer, sometimes teaching university classes, traveling during the summer. Then the real estate market crashed in 2008, taking my wife’s and my investment in a condo project and our hopes for a secure future down with it. Now I was paying the price. Bad judgment, bad timing.

Karl made his way to me and eyed my beard. “You’re Watt, aren’t you? You can work titles?” He handed me a thick file.

I nodded and headed south.

For the next several weeks I spent eight hours a day examining county records, running indexes, tracing the lineage of heirs, and puzzling over ambiguous and often contradictory mineral deeds. The old courthouse in Cotulla was undergoing a restoration, so the records were temporarily housed in an abandoned school. The older record books weighed twenty-plus pounds, and in an average day I handled forty to sixty books, hauling them off the shelves and out into the hallway, where folding tables lined the dark, high-ceilinged space.

I had intended to use early mornings and evenings to write. Instead, I used my downtime for recovery. At night, I’d watch the Spurs and drift into uneasy sleep before halftime.

Late on Friday afternoons I’d make the three-hour drive home to Fredericksburg, where I’d collapse, almost worthless for two days. Then on Sunday evening I’d leave my wife and cat and ease back into my pickup, heading down I-10, south to Pearsall.

Some evenings I joined my fellow landmen at the Hungry Hunter, a barnlike restaurant near the hotel, always oil-boom packed. One night, over chewy steaks and overstuffed potatoes, one of my co-workers, a skinny young guy with spiky black hair, started going on about needing a gun, a hybrid semiautomatic, even though he admitted to owning 27 guns already. Between swigs of Bud Light he made a series of phone calls, circling a chunk of steak in a pool of A.1. sauce while he talked. Finally, he waved his fork in the air and shouted, “I found one! Down in McAllen. They’ll hold it for me if I can pick it up Friday.” He glanced over at Larry, the crew chief. “If I can sneak off.”

Larry lifted his beer. “I’ll drink to that,” he said, and everyone laughed.

I felt uneasy with the gun mania, but I stayed quiet. I needed the work, needed the money. I pushed back from the table and made my way to the men’s room.

One day, after three months of trekking back and forth from Pearsall to Cotulla, I received a new assignment. Now, instead of a thirty-minute commute along I-35, I would drive more than an hour along a series of smaller roads through the heart of the Eagle Ford field to Tilden, the McMullen county seat.

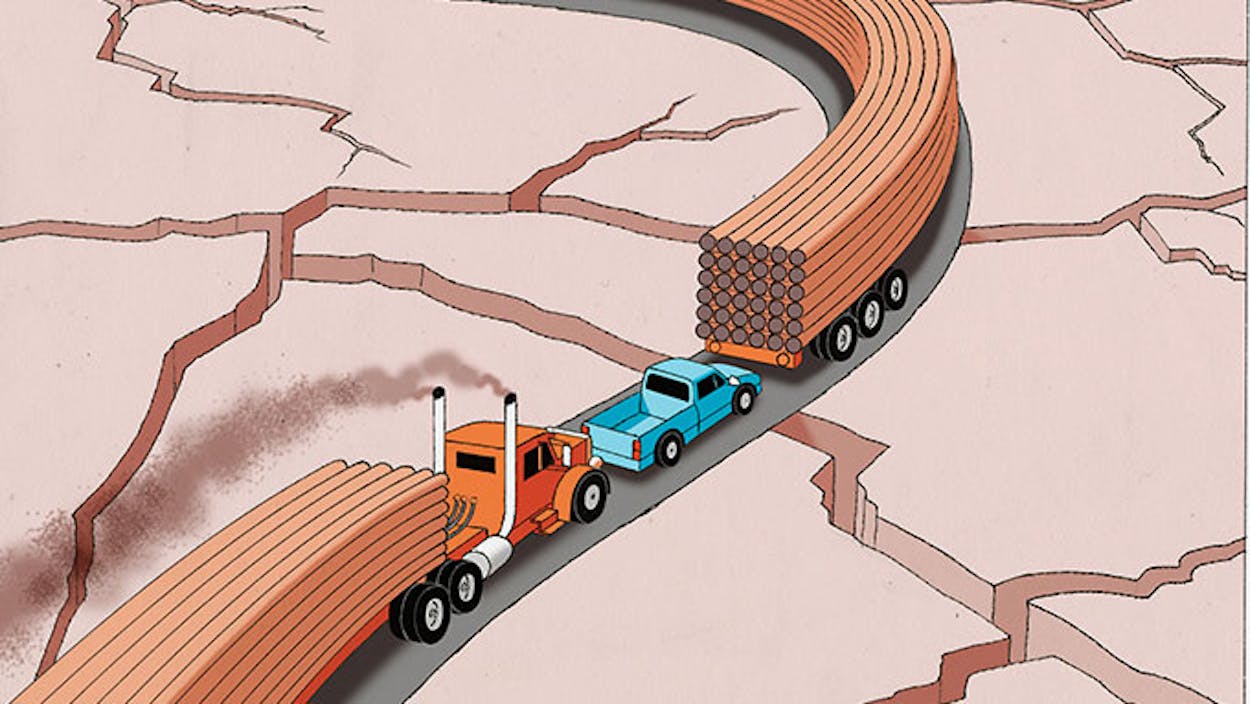

The next morning I pulled onto FM 1582, a narrow two-lane blacktop, merging into serious oil-field traffic. For the next fifty miles I gripped the steering wheel and kept as far from the center lines as possible, but I cringed every time I met a row of top-heavy eighteen-wheelers hauling dozers or drill pipe. A white pickup rode my back bumper, the driver desperate to get around me and the string of trucks we were stuck behind. I could make out four men packed across the pickup’s front seat.

To the left and right, derricks stretched as far as I could see, and flames flared from completed wells. White caliche roads led straight and flat to rigs or storage tanks. Mesquite trees stood bare and bent in bar ditches half-filled with sludge. No deer, cattle, or horses in sight.

It all looked so ravaged, the land chewed up, and I couldn’t help but feel complicit in the destruction. Everyone, it seemed, from those of us driving through the oil field to the daily commuters in Dallas and Houston and beyond, was consuming what was being fracked from under this South Texas wasteland.

About a mile outside Tilden, I pulled off at a truck stop. Still shaky from the drive, I made my way in past roughnecks and truck drivers. I inhaled cigarette breath and the sourness of sweat from their hard labor. In this place, time was irrelevant. Oil fields ran on a 24-hour clock, day and night merged as one.

I grabbed a bottle of water and a foil-wrapped chorizo-and-egg taco, then went out to my pickup and sat on the tailgate. I ate leaning forward so the grease from the chorizo would drip between my legs. Across the road a field of mesquite lay undisturbed, and I spied a scissortail dancing on a barbed-wire fence, a respite from the overwhelming chaos. Then a line of flatbed trucks loaded up with monster dozers pulled in and blocked my view.

With the last bite of my taco, I stood and wiped my fingers on my jeans. No more, I thought. I’ve had enough.

I ran my pickup hard, straight over to I-35, then north to Pearsall.

Outside the hotel Larry was pacing and smoking, looking harried. I paced with him for a minute, letting him know I was headed home for good. “I’ll be seventy-two in a couple of weeks,” I said. There was more I wanted to say, but that seemed reason enough for him.

“Sorry to see you go,” he said. “You were a hard worker. If you’ll hang around, I’ll buy your dinner.”

“Thanks,” I said, “but I need to get home.”