This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When I was a kid in Colorado, all my friends were collecting baseball cards, none of which bore the mugs of my heroes, who were mostly entomologists. Forced to a more direct route to my idols, I talked my mom and dad into going to the 1961 annual meeting of the Lepidopterists’ Society, an international organization of butterfly and moth scholars, held that year in Gothic, a lost-in-the-mountains ghost town in Colorado that houses the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory. All the gods of lepidoptery were there, including Yale’s C. L. Remington, a pioneer in the study of butterfly chromosomes, Stanford’s Paul Ehrlich, whose field is the population biology of butterflies (and of people—he is the author of The Population Bomb), professors from the major universities, and many of the curators of the large natural history museums. Roy Kendall was there, too.

In the small universe of lepidopterists, Roy Kendall occupies a special niche midway between amateur and highly trained scientist. Kendall, a retired civil servant who lives in San Antonio, is a self-taught field researcher—a naturalist whose main objective is to observe living creatures. His is a school of investigation that combines the enthusiasm of a novice with the critical eye of a scientist. Both traits describe Kendall, and it is not surprising that amateurs and topflight biologists alike turn to him for information.

During those four days in Gothic, the professors delivered papers on chromosome studies, genetic drift, and a new desert butterfly discovered in New Mexico that year. But it was quiet and self-effacing Roy Kendall who stole the show with his techniques for rearing and studying butterflies and moths. To me, Kendall demonstrated outdoorsmanship at its best. He would meander around the meadow fringes, following a lone female butterfly that he somehow knew was going to lay eggs. He would capture her alive, collect her eggs as she laid them, and raise the caterpillars in his laboratory so that he could learn the early-life habits of that species. He showed me how to tell when a butterfly was going to lay eggs. I was amazed to know that I could know that.

He told me that butterflies had affinities for specific plants—that one butterfly’s caterpillars would feed only on one particular plant—and that lots of species were still unstudied and their food plants unidentified. It seemed to me that Kendall knew more than anybody else in the country about butterfly life histories (that is, the eggs, caterpillars, chrysalises, and adults). I was fifteen, and it would be years before I would discover that this scientist, whose studies of life histories and collections of data and immature specimens ranked with the finest in the country, didn’t even have a college degree.

Kendall studies butterflies with equal emphasis on all the life stages, hence he is skeptical of any taxonomy based only on the color, pattern, and morphology of adults. This naturalist’s point of view is growing among lepidopterists and in recent years has begun to pay off. In some cases, look-alike species that masquerade as the same butterfly can be easily told apart by comparing their caterpillars, chrysalises, or food plants. The sooty azure (Celastrina ebenina), for example, was for years confused with the spring azure (C. ladon), which it closely resembles. It is identifiable in nature, however: its caterpillars feed on goat’s beard, while the caterpillars of the spring azure feed on numerous other plants.

Kendall, more than any other individual, has provided the inspiration for that angle of research. For almost thirty years now, he has been taking notes on the life histories of butterflies in his laboratory and in the field. The field for Kendall begins in his front yard and stretches to the most inaccessible places in Texas, the Southwest, and northern Mexico. His current assignment is to distill some 25,000 pages of his notes into an opus on Texas butterflies, which the University of Texas Press is planning to publish. Kendall clearly has his work cut out for him. Texas has well over four hundred species and subspecies of butterflies, more than any other state. They range from the smallest to the largest in North America, and from tropical strays to cabbage pests.

Between 1961 and 1979 Kendall and I didn’t exchange a word. I was off doing all manner of other things, but old habits die hard, and when I moved to Austin and ran across a tiny blue and gray butterfly whose life history was a total mystery to science, I fell into a study that led back to the man who had caught my interest eighteen years before. I called Kendall and asked what he knew about Calycopis isobeon, my blue and gray butterfly. He remembered me as well as I remembered him. We reminisced about Gothic, then I made an appointment to see him.

Approaching Kendall’s house on the outskirts of San Antonio, I was first impressed by the absence of a lawn—ample space, cleared ground, but no lawn. Instead, a roughly tended field of weeds spread on three sides of the house. But they were not ordinary roadside weeds, blown in and squatting. They were special weeds, carefully selected to attract butterflies. Some of them had showy blooms, especially those near the house, but most of them were simply weeds. Only someone with an obsession like mine could love a yard like that. Here, obviously, was a man to whom a Baccharis bush was as precious as a fine fly to a fisherman. He waved to me from the house.

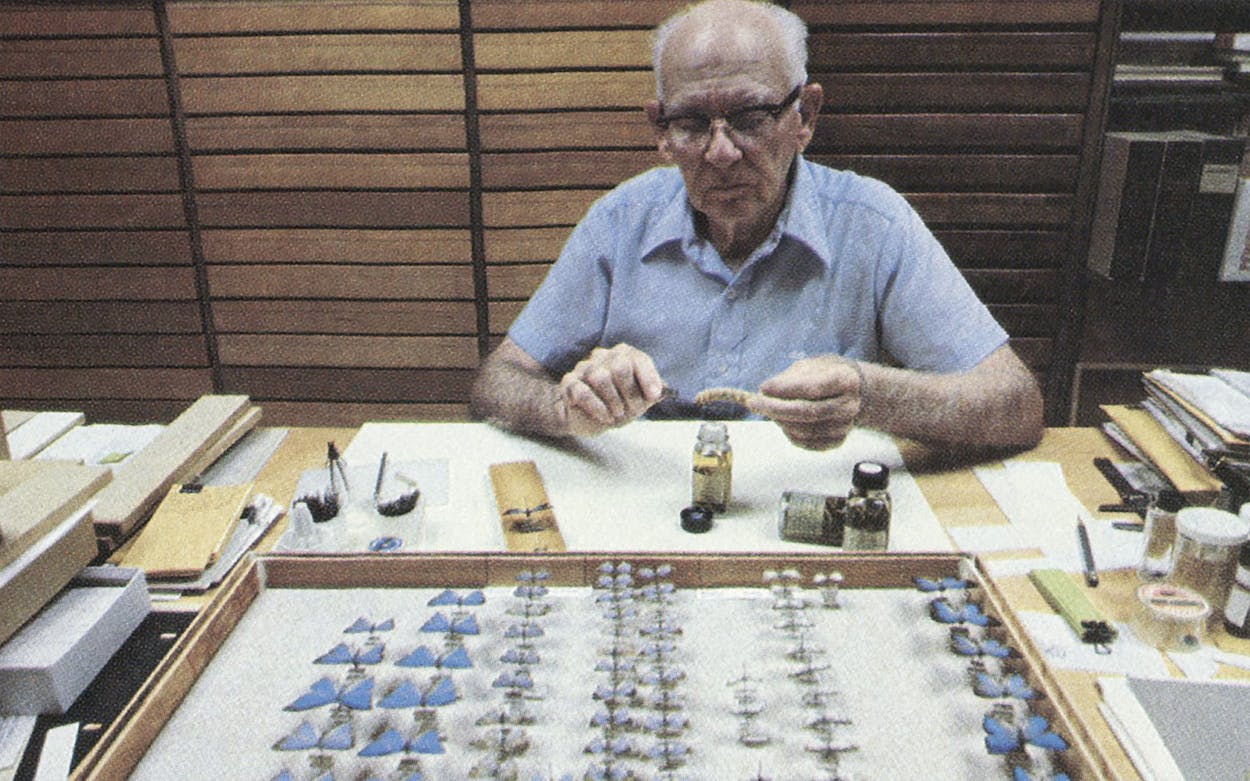

Though at 70 he was graying a little and stood a bit shorter, he hadn’t changed much since I was a kid. Connie, his wife of 35 years, also came to greet me. She and Roy have raised two kids and a hundred thousand caterpillars, and she always goes along on his forays in search of butterflies. I got a tour of the “garden,” then of the laboratory—a well-lighted, spacious area that took up about a quarter of the house. This was no basement operation. The ceiling of the lab was ten feet high, with opposing walls stacked with specimen cabinets; I counted about 350 trays, most of them full of butterflies and moths. File drawers bristled with thousands of vials of pickled caterpillars and chrysalises, and bookshelves contained thousands of scientific papers, journals, and texts.

Kendall is always rearing something or other. At times he has hundreds of caterpillars of dozens of species surrounding him in his laboratory. When I asked what he had going, he opened a box and revealed several hundred large brown chrysalises covering the bottom. “Hemileuca moths,” he said, “possibly an undescribed species. They’ll hatch in November, when it cools off.” Hemileuca means “half-white,” and these would turn into big, velvety brown or black moths with white bands. I would hardly have imagined that this late in the game, anyone could discover a new species of something so conspicuous and gaudy.

We talked butterflies, a somewhat bewildering but highly educational exercise. Sample: “Gravid Calycopis females will oviposit on anything for me,” I said, “but I caged Phaeostrymon alcestis on Sapindus and got nothing in three days.” Kendall replied, with a wink, “Well, you didn’t read my paper on Phaeostrymon. They only lay in last year’s leaf scars—they need stems, not leaves and flowers.”

In spite of all this, I was still surprised when he pulled from a drawer an inch-thick file on Calycopis isobeon. I assumed at first that the file was on the hairstreak butterflies in general, a group that includes C. isobeon, but the entire fat file was on nothing but my own little blue and gray butterfly. It held data on where and when the species had been taken, which flowers it had been taken from, attacks by predators like crab spiders, courtship flights over tall trees in the evening, mating behavior, and egg laying. He had even reared one brood partially on Croton, or goatweed. Looking over those notes, he said, “You see, we don’t know much about this butterfly. It’s a bizarre little thing.”

I spent the rest of the afternoon taking notes and getting ideas from Kendall. I looked at his specimens, not only caterpillars but parasites of caterpillars (the latter he would send to the Department of Agriculture in Maryland for identification). I even found specimens of hyperparasites—that is, parasites of parasites of caterpillars.

Although Kendall’s interest in butterflies can be traced to his childhood, his systematic pursuit of the subject did not begin until he and Connie moved from Louisiana to San Antonio in 1947. Working as a cost analyst for the military, Kendall spent his spare time doing research, until his hobby had expanded beyond his available space. Then he bought land outside the city limits and designed a house that would accommodate his studies. Since his retirement in 1972 he has been studying butterflies nearly full time. He has written numerous scholarly articles and in 1963, along with H. A. Freeman of Garland, wrote the only definitive list of Texas butterflies ever published. Though he refuses to name new species—he leaves that to taxonomists—so far two butterflies and two moths have been named after him.

Kendall’s calm approach to his passion doesn’t fit the image of the wild-eyed fanatic hurtling through the jungles with a long-handled net whipping the sky, but his zeal has taken him and Connie into some pretty hair-raising situations. Once, on a collecting trip into the Chihuahuan Desert southwest of Presidio, traveling in a four-wheel-drive Scout, the Kendalls ran into a solid week of rain. They returned north on the muddy roads to Ojinaga, where they learned that the bridges were underwater and had probably washed away. Unable to cross the Rio Grande to Presidio, they took a motel room for the night. But rising floodwaters threatened to swamp the motel, so they fled in the night to a hilltop, where they stayed till morning. The roads promised to be impassable for a long time, so they set off south, crawling through the muck in the four-wheel-drive, seeking a crossing back into the States. A half-dozen impromptu river fordings and a thousand miles later, they dragged into Laredo with a few specimens they wouldn’t soon forget.

Besides Kendall’s work, there is considerable butterfly research going on in Texas, especially at UT-Austin. In fact, Texas lepidoptery began in the 1840s with the European colonists, so it might be tempting to assume that by now the butterflies of the state have been studied right down to their scales. But that is far from the truth. New findings are turning up on a regular basis, and the life histories of many species remain unstudied. Nor is the Texas environment in a steady state. Some species seem to have shifted their ranges considerably in response to the ice ages and are still adjusting to climatic changes. Carefully kept records will show their subtle geographic drift as the environment changes. Amid the flux, lepidopterists are having a grand time of it. Butterfly collecting is a wonderful excuse to camp and hike, even if one isn’t a professional entomologist. Identifying butterflies, learning their bright patterns and dances, and figuring out the look-alikes simply makes the outdoors a richer, if occasionally perilous, place to be.

I once asked Kendall what his favorite butterfly was.

“It isn’t that way,” he said. “They’re all interesting to me. And every specimen, however ragged or shabby, is unique.”

Then, as if to indulge my weakness, he produced a drawer of some of the most exquisite butterflies I’d ever seen, their blue and green iridescences flashing like neon. I turned one over and over in the light. It was a species from Mexico. He had reared a boxful of them.

“Do you think this thing will ever turn up in Texas?” I asked.

Kendall smiled broadly and glanced at Connie. “We’re looking.”

The Netting Game

The butterflies are out there; catching them is another matter.

Butterflies like bushes. That’s why your back yard is a good place to start looking for them, but since that won’t give you the thrill of the quest, proceed to a trail through the woods near a creek or spring (many butterflies are partial to water), to tangled vines along a river, or to shrubs at the base of a cliff. Or find a hilltop. For reasons not yet known, male butterflies will gather on an open summit and fritter away the day in endless fights for the choice resting places. Distracted by their disputes, they are easy prizes for collectors. In twentieth-century Texas, one of the best places to look is on the edge of town, assuming your town is responding to the Sunbelt boom. Ranches and farmlands that have been bought up by developers lie fallow there, allowing the plants and butterflies to come back. Of course, your favorite place one season may be a housing tract by the next.

Texas’ rivers are favored spots for butterflies—and collectors. The Guadalupe River is especially rich, and so is the stretch of the Nueces River north of Uvalde in the Hill Country and of the Brazos River north of Lake Granbury. National and state parks are good places for looking at—but not collecting—butterflies; it is illegal to take specimens without a permit in those places. In the looking-only category some of the stellar spots are Palo Duro Canyon State Park in the Panhandle, Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains national parks in West Texas, and Bentsen–Rio Grande Valley State Park and Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge in the Valley. County and city parks as a rule don’t ban butterfly catching (but check with your local authority). In the proper season, McKelligon Canyon park in El Paso, Landa Park in New Braunfels, Zilker Park in Austin, and Anzalduas County Park in the Valley near Mission are excellent places for netting butterflies.

Butterflies, however, don’t distinguish between a bush in a park and one on a farm-to-market road—a fact you would do well to remind yourself of. Unfortunately, a lot of people feel funny about going out-of-doors if out-of-doors hasn’t been designated a park. Becoming a butterfly collector requires overcoming that inhibition. In Texas, you also have to learn the subtle art of asking permission to go onto private land.

You will get the best returns netting butterflies after a spell of rain, which triggers the growth of vegetation and flowers, and during the heat of the day, after the sun has warmed up these cold-blooded creatures so they can fly. (This is a matter of degree, though; if it gets too hot, most butterflies head for the shade.) The best butterfly time will usually come about two weeks after the spring rains start in your area. But the weather is never usual in Texas, and many butterflies are cued out of their resting stages by seemingly random showers. Over much of Texas, good butterfly finding depends on simply being in the right place at the right but unpredictable time.

Although spring and fall are the best seasons, in winter the butterflies are still hopping in the tropically tinged Valley. It is there that thrilling exotics—like the big Montezuma morpho pictured on the opposite page—stray into Texas from Mexico. But if you see a strange butterfly down there, or anywhere, you’ll have to collect your evidence; the experts seldom accept sight records as proof of a species’ occurrence.

A veteran lepidopterist makes getting a net around a butterfly look easy; it is not. It requires a lot of sprinting, jumping, and quick stopping. Think of it as good exercise. Use a net with a long handle, strike at the butterfly with enough force so that it will swoosh to the back of the net, then flip the rim across the bag to close it. A backstroke is quite effective. Nets can be ordered from Bio-Quip Products, Box 61, Santa Monica, California 90406, one of the few sources of butterfly-collecting supplies.

Collecting does not harm populations of butterflies (that takes sweeping events, like storms, drouths, and man’s tampering with the habitat), but if you are netting butterflies simply to see them up close, there’s no need to kill your catch. Maneuver the netted individual into a large Ziploc bag, where you can hold it gently for study, and then release it. If you do want to start your own collection, consult Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s How to Know the Butterflies. First, though, you should memorize the first commandment of collecting: thou shalt write down where and when you collected each butterfly on the envelope that you put your specimen in. That will make Roy Kendall happy.

Christopher J. Durden

Two Giants and a Pygmy

Contenders for Largest

For years lepidopterists have designated the giant swallowtail (Heraclides cresphontes), below, as the largest butterfly in North America. That’s because the experts weren’t measuring specimens of the two-tailed tiger swallowtail (Pterourus multicaudatus), right, from Central Texas, which can outgrow the giant swallowtail by a couple of millimeters; some individuals have a wingspan of 149mm (5.877 inches). The title must pass to P. multicaudatus. These outsized, loudly patterned butterflies would seem to be easy targets for predators, but they are artful dodgers; try to catch one sometime.

Texas’ Smallest

The Western pygmy blue (Brephidium exilis), with a wingspan of barely half an inch, may be the smallest butterfly in the world. Presumably its pint size makes it hard for predators to see; that hypothesis is supported by the fact that most human observers overlook B. exilis, even in South Texas where it is common year round.

The Commoners

The Traveler

The monarch (Danaus plexippus), left, is the only truly migratory butterfly in the world. It makes a regular odyssey from Canada to Mexico and back every year, laying eggs on milkweed along the way north. The peak months for the monarchs’ passage through Texas are October and April. They winter by the millions in central Mexico—in remote canyons that were discovered only in 1976.

Most Familiar

The sleepy orange (Eurema nicippe), right, flies in lurches, as if it had just wakened from a nap. It occurs all across Texas and can be seen year round in the southern half. In the colder parts of the state, E. nicippe hibernates—an unusual trait among adult butterflies and another reason to call this one sleepy.

Garden and Roadside Companion

The pipevine swallowtail (Battus philenor), below, has expanded its range wherever pipevines, on which its caterpillars must feed, are cultivated. But in Texas these butterflies are just as content in overgrazed pastures and vacant lots. One species of pipevine looks just like lawn grass, so botanists studying that plant let pipevine swallowtails pilot them to the plants they want to find.

Beginner’s Delight

The great blue hairstreak (Atlides halesus), above, the crown jewel of Texas butterflies, is too dazzling for collectors, especially novices, to pass up. However, it is by no means a rare jewel; it occurs wherever there are trees decked with mistletoe, which is the required food plant of the great blue caterpillars.

Most Down-home

The dusky blue hairstreak (Calycopis isobeon), above left, is pretty relaxed—you are likely to see it sitting in the shade in your back yard. The caterpillars are omnivorous, eating poison ivy, leaf trash, dead insects, and other rotting debris.

The Rare and Elusive

Swiftest

At 60 miles per hour, the giant skipper (Megathymus coloradensis), left, flies so fast that collectors find it easier to obtain specimens by digging up the chrysalises—they live in the roots of yuccas—and raising the butterflies at home.

Most Exotic

The Montezuma morpho (Morpho peleides), below, is a dazzling Mexican species that has been sighted only once in Texas—in the Valley, near Hidalgo, in 1945. Mexican farmers consider morphos omens of prosperity; to kill one is to court crop failure.

Most Endangered

The Balcones metalmark (Calephelis sinaloensis), above, is rare indeed. There are seven known colonies in the mountains of Mexico; six sites have been found in Texas—all of them around Austin—but unfortunately, one of those was destroyed by a parking lot and another by spring floods in 1981.

Texas’ Newest

In 1968 Roy and Connie Kendall collected a female hairstreak in the Big Bend that just didn’t fit the descriptions of any known species; in 1971 they captured a male. Christopher J. Durden of Austin has since collected more specimens. This butterfly, below, still has no scientific name, but its common appellation is Solitario hairstreak.

Hard to Pin Down

Well, not literally, but the dotted checkerspot (Poladryas minuta), above, is elusive in terms of its range and status. Lepidopterists were pretty sure it was extinct—it does seem to have vanished from its Hill Country range—but at least one healthy population has been found near Wichita Falls.

The Carnivore

The harvester (Feniseca tarquinius), above, is the only meat-eating butterfly in North America—its caterpillars attack woolly aphids! They even wrap themselves in aphid wool and prowl among their prey like wolves in sheep’s clothing.

Samuel A. Johnson is a math and science teacher who lives in Austin.

- More About:

- Wildlife

- TM Classics

- San Antonio