This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On a hot, unlucky July morning in Parral, Chihuahua, in 1923, a 45-year-old retired revolutionary general, two bodyguards, and two old comrades climbed into a Dodge Brothers touring car and headed out of town. Though he was usually chauffeured, this time the general decided to take the wheel himself. As the Dodge neared a square called Plaza Juárez, a man in peasant’s clothing stepped into the street and raised his sombrero, as if in salute. The general slowed his car, perhaps to return the peasant’s greeting. But the peasant didn’t shout. “!Viva la revolución!” or any of the other cheers that the general was accustomed to hearing. Instead a comrade yelled, “!El perro viene manejando!” (“The dog is driving!”) The sombrero hadn’t been raised in greeting either. It was the signal for shooting to begin. Volleys of pistol and rifle fire tore into the Dodge, which entered a turn, then wandered off and came to a stop, as dead as its driver, against a curb. Six, seven, or eight assassins—historians can’t agree—continued firing into the car’s hull. When silence came a few moments later, legend says, a man in a straw hat walked up to the Dodge and surveyed the death within. Just to make sure, he drew a revolver and shot the driver in the head; then he ran off. Within hours, postcards of the bloody scene were being sold on the stunned streets of Parral, testifying to the demise of General Pancho Villa. By nightfall the entire civilized world had been told that Mexico’s master revolutionary was dead. But thousands did not believe it, and some of the doubters—presumably those who benefited by Villa’s execution—demanded incontrovertible proof.

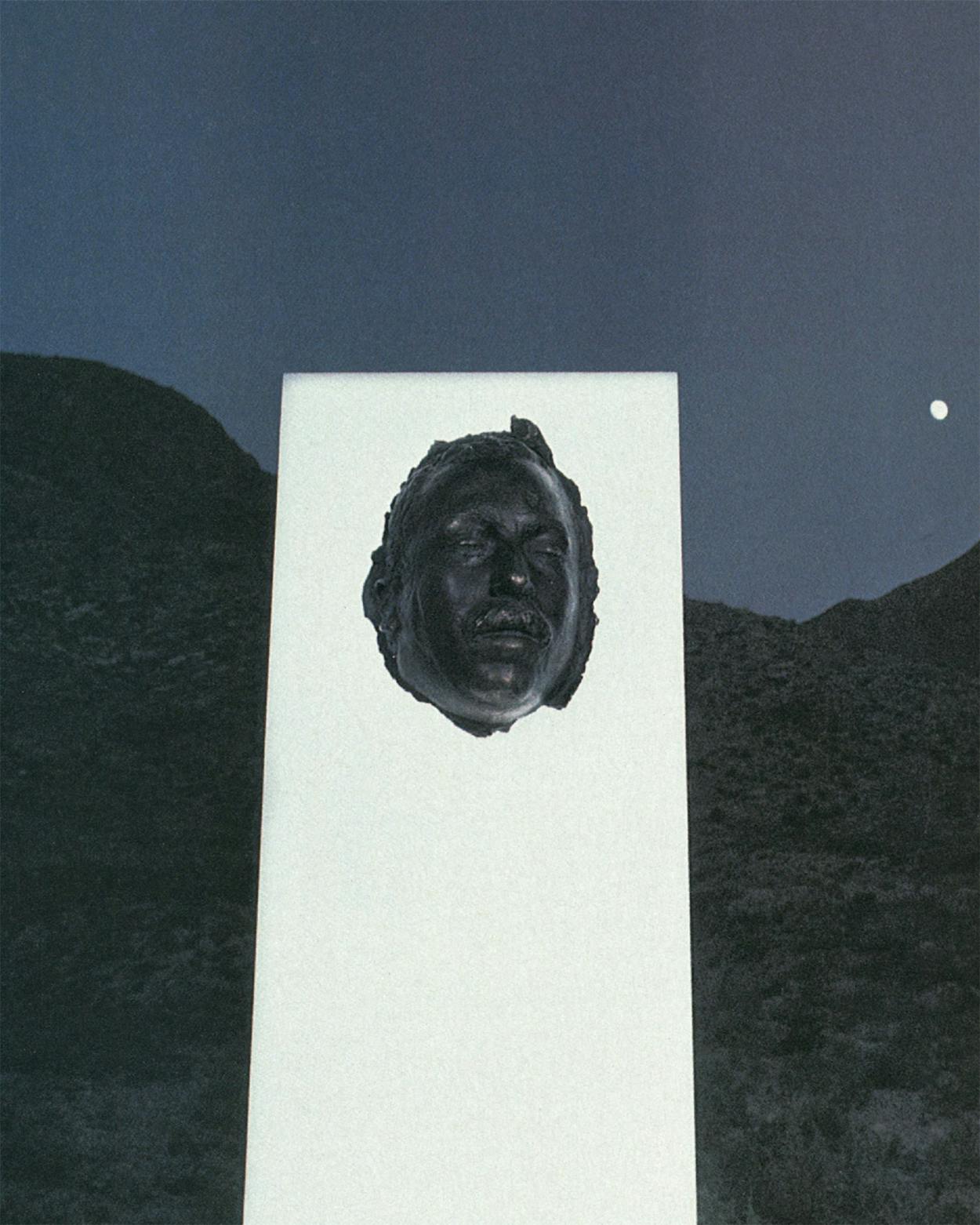

More than a century later a young art instructor at a private school in El Paso found that proof among the items of an odd and almost forgotten collection of memorabilia that had belonged to a former director of the school. He had rummaged through a basement, an attic, several wall compartments, a safe, and a vault and had come across military insignia, live bombs and ammunition, a note from a Prussian king, and even several letters written by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. On a shelf in the vault, in a cardboard box whose sides had rounded and collapsed under the strains of age and handling, the art instructor found a plaster cast—a death mask—white on one side, reddened with varnish and blood on the other. Bits of flesh and hair were embedded in its concave surface. An entry in an old clothbound ledger gave a name, and the face preserved in the mask was identified by scholars: it was Villa, all right. There was a bullet hole in the forehead.

The reappearance of Villa brought an old question back to life: Just who was Pancho Villa anyway, villain or hero? And it generated a new one: What country has a right to the death mask? Americans have had the mask for years, but it now looks as though the relic will soon be on its way back to Mexico. Yet, because the battle for ownership of the mask is being waged by legislators, lawyers, governors, and diplomats rather than by generals in the field, the fight could outlast the Texas Revolution, the Mexican War, and Villa’s uprisings combined.

Lives of the Bandit

Doroteo Arango, the man we know as Pancho Villa, inspires controversy even from beyond the grave. He is the beneficiary of diminished memories and fortified myths. There are no unbiased recollections of Villa, only sympathetic anecdotes, bitter denunciations, lies, legends, and the contradictory reports of the historical record. Even the borderland’s curanderos are perplexed. In their amalgam of Catholicism and witchcraft, Villa is a man to be revered—as the patron saint of revenge.

Doroteo Arango was born on June 5, 1878, on a farm in the desert state of Durango—at ten minutes past midnight, during a drenching rainstorm, legend says. His parents were sharecroppers in a semi-feudal economy; by law, men of Doroteo’s caste inherited the debts of their fathers at birth and, because there were no schools for peasant children, they inherited the destiny of illiterates as well. According to legend, Doroteo was sixteen years old and working to pay off his dead father’s legacy when he returned home from the fields one day to learn that his patrón had raped Martina, Doroteo’s younger sister. The young farmhand immediately got his pistol, shot the hacendado, and fled to the hills.

He appropriated the name of a dead but notorious bandit named Francisco “Pancho” Villa. For fifteen years Villa waylaid drovers and hacendados, and supposedly he and his gang distributed their take to peasants in need. In those days, Villa would later say, he didn’t agitate for revolt because he believed that only rich, educated men could oust President Porfirio Díaz.

Díaz, the darling of European investors and the nightmare of the poor, was also the embarrassment of Mexico’s tiny but democratic-minded middle class because fraudulent elections kept him in office for 34 years. In 1910 Francisco Madero, the timid, vegetarian, and mystic son of a prominent Coahuilan family, opposed Díaz in the presidential elections. Though Madero probably bested Díaz, fewer than two hundred votes were tallied to his name. Madero’s infuriated backers urged him to go north to Texas, where conspirators already had a revolution in mind. In meetings at a hotel in San Antonio, radical firebrands made Madero their chieftain and persuaded him to ask for support from the nation’s boldest horsemen, the desperadoes of Villa’s gang.

Villa joined the revolt, and early in 1911 Madero, Mexico’s apostle of democracy, pardoned the bandit for his past crimes and anointed him a colonel in the army of the revolution. Several months later Villa and Pascual Orozco decided to lead their troops in an assault on the city of Juárez, despite orders to the contrary from Madero, who, Villa noted in his autobiography, “was no military man.”

The unauthorized attack was successful and signaled the end of the Díaz regime, but the coalition of revolutionary leaders—never united by anything other than opposition to the dictator—immediately came apart. President Madero ordered Villa to serve under the alcoholic general Victoriano Huerta in a drive to subdue the rebellious Orozco. The campaign was militarily successful, but as soon as victory was achieved, Huerta ordered a tearful Villa shot, on charges that he had needlessly sacked Parral. As Villa stood facing the firing squad, his back to the wall, a last-minute stay of execution arrived from Madero. Villa was sent to Mexico City for imprisonment and trial. “Señor Judge,” he told his military inquisitor, “there is money in the banks, and when our cause is in danger, that money is offered voluntarily or we take it.” Doubtful that his argument had been persuasive, Villa escaped from the prison and fled to a hotel in El Paso.

It was a fitting town for an exile like Villa. El Paso was a mining and smelting center, a railroad terminus, and a military town, with unpaved streets and buildings of adobe. It also served as a supply depot for outlying farms and Mexican importers. The city had grown too rapidly—its population doubled between 1900 and 1910 and redoubled by 1920—mainly because of an influx of refugees from the revolution. Rapid growth brought vice; travelers of the time compared El Paso to Singapore, Istanbul, and Marrakesh, places where money could buy anything. The city’s border location and the designs of industrial powers attracted German spies and Japanese provocateurs, and Villa’s own anti-Chinese pogroms had sent Mexico’s Oriental population north to El Paso in droves. El Paso was not a melting pot; it was a boiling pot of nationalities and men with desperate ambitions.

Villa and the revolution had always been welcome in El Paso, in part for political reasons, in part for the effect the revolution had on commerce. Porfirio Díaz, because he favored Britain’s interests rather than America’s, was not popular north of the Rio Grande. But Villa had once ordered in El Paso 40,000 pairs of shoes, 40,000 pairs of khaki pants, hundreds of thousands of rifle shells, tons of sugar and canned salmon—and he paid for it with boxcars of bullion stolen from Mexico’s mines. After his fall, Villa was able to keep in touch with his cronies in El Paso while waiting for their next opportunity in Mexico’s unfinished revolution.

It came in 1913. Madero was ousted and executed in a coup led by Villa’s nemesis, General Huerta. Once again Villa formed a revolutionary army, 10,000 strong. His Division of the North battled across Mexico in 1913 and 1914 and grew rich on loot taken from mining trains.

Villa became the de facto emperor of northern Mexico. He had trains and plush private railroad cars at his disposal; his entrance to conquered towns was heralded by trumpeters; his government minted its own money, set up schools for the poor, and gave land to the tillers. But Villa was dangerously unpredictable, and his troops were notorious. After men of his division murdered a woman’s husband, Villa ordered that compensation be paid to her; but when a man complained that Villistas had raped his wife, his compensation was gunshots to the knees. Villa refused to let anyone know where he planned to sleep at night, he traveled with his pockets full of peanut brittle, and with the capture of each town he sent his soldiers out in search of canned asparagus for his supper table.

Upon seeing a lovely woman in a conquered town, he would send for a magistrate and have the surprised bride brought to him for a quick wedding ceremony. His hurried honeymoons left northern Mexico with hundreds of Villa children and more than forty abandoned wives. He regarded most of his marriages as fraudulent adventures, but seven of them, he told a friend, were genuine matters of the heart.

In August 1914 the revolutionary armies headed by Villa, peasant leader Emiliano Zapata, and a former schoolteacher named Alvaro Obregón, forced Huerta from office. He was replaced by Venustiano Carranza, a moderate who trusted neither the radical Zapata nor the volatile Villa. Obregón, under Carranza’s command, moved to destroy the Division of the North. Supplied by the kaiser with ways and means of twentieth-century warfare—land mines, barbed-wire traps, machine guns, and trench tactics—Obregón’s soldiers humiliated Villa’s bold horsemen in April 1915. More than four thousand Villistas died, twenty times the number of federal casualties. Among the wounded, however, was Obregón, who lost his right arm to a shell fragment and never forgave the wound.

Though Villa had successfully courted the United States, President Woodrow Wilson declared support for the Carranza regime, following Villa’s eclipse in the new civil war. In early 1916 Villa’s men responded at Columbus, New Mexico; they murdered eighteen civilians and set the sleeping town on fire. Wilson dispatched General John J. Pershing and six thousand soldiers to Mexico with orders to capture Villa.

Under the pretext of defending national security, Carranza’s troops moved north, shoulder to shoulder with Pershing into the middle of Villa’s stronghold. The combined presence of Villa’s Mexican and American pursuers drove the former bandit into the wilds. Northern sympathizers concealed Villa’s whereabouts, erected tombs that bore his name, and pelted newspapers with reports and notices of his demise. But Villa was not dead. In 1917, when the norteamericanos returned home to prepare for war in Europe, forty-year-old Villa reemerged, weak but still a menace.

His renewed efforts were trivial compared to the victories of the past, and by 1919 the Carranza government had turned its attention to Zapata’s peasant rebels in the south. Under the banner of a truce, it lured Zapata into view, and he was betrayed and murdered. A year later an exhausted Villa, having buried his hopes for a new uprising, agreed to talk peace. In exchange for a ranch, full pay as a general, and fifty men as guards, plus concessions for his remaining troops, he gave up his revolution.

Villa bought tractors and combines for Hacienda Canutillo, his 25,000-acre ranch. He hired an American to oversee grain and poultry production. Several of his wives joined him, and he opened a school for his numerous children and those of his farmhands. In the style of prerevolutionary Mexican gentlemen, he wrote letters to his friends on embossed stationery ordered from England. He was a kind patrón, his underlings said, but a patrón nonetheless. Supporters continued to insist that Villa was not a rich man, a bloodletter, or a traitor to the cause of the poor.

Even in 1923, after the bandit’s blood had dried on the streets of Parral, Villa’s loyal followers maintained that he would reappear one day. The belief that Villa was still alive may have inspired a footnote to his mysterious public career; in 1926 someone cracked the seal on his crypt and carried off his head. The head, which was probably delivered to one of Villa’s old enemies who wanted to be absolutely sure that Pancho was dead, has never turned up. In Mexico, rumors persist that it is in American hands, and one of Villa’s widows, named Luz Corral, for years before she died periodically demanded that it be returned.

A Grisly Gift

On the borderland during Mexico’s decade of revolution, life was dangerous even for children. Prosperous Mexican and American families needed—and sought—fortresses in which to school their offspring, especially their daughters. In 1910 a group of ranch and mine owners financed one such haven, called the El Paso School for Girls. The institution was to provide “those special advantages of instruction and training which a superior private school offers,” as well as physical security. To ensure the serenity of their daughters, the founders located their adobe and tile-roofed school at the gate of the safest spot in Texas: Fort Bliss.

The El Paso school prospered during the revolution, but by 1928 enrollment was perilously low. The businessmen who sat on the school’s board decided that without a director who could boost its reputation, the school might go bankrupt. They searched the country for a savior and found an eccentric but well-regarded Missouri educator, Lucinda de Leftwich Templin. She persuaded tobacco millionaires George and Julia Radford to pay off the school’s mortgage and to endow the institution; the El Paso School for Girls became the Radford School. According to the terms of a trust created for the school, Templin was to be its director for life.

With a cadre of local advisers, she led the school to regional prominence and saw to it that her girls, ages six through eighteen, looked and behaved like ladies. Templin didn’t shrink from expelling girls for violating Radford’s lengthy codes of comportment; one girl was sent home for buttering a slice of bread with her finger. The school’s success attracted notable visitors, people like Clare Boothe Luce, Jeanette MacDonald, Will Rogers, and Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum. And Radford produced its own luminaries, among them Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

As the school’s stature grew, the cigar-smoking Templin cultivated her idiosyncracies. She built a collection of military memorabilia that included ivory statues of Napoleon, prints of his funeral, and etchings of battle scenes. She talked of building an artillery museum on the school grounds. Her reputation both as an educator and as a collector drew the attention of Otto Nordwald, a German American merchant in the city of Chihuahua who wanted an English-language education for his daughter, Ruth. In 1932 Nordwald brought eleven-year-old Ruth to Radford.

Nordwald had been an acquaintance and an admirer of Pancho Villa and, during the revolution, had many times done business with Villa. Like anyone who had survived the revolution, he had learned how to extend friendship without completely compromising his integrity. Once, while Villa and his guard visited genially with the family on the porch, Nordwald’s mother kept a dozen Chinese workers hidden in the basement, for Villa often had Chinese shot on sight.

After viewing Templin’s collection of military relics, Nordwald decided that she could help him solve a peculiar problem. A few months after Villa’s assassination a Mexican army officer, who was a stranger to Nordwald, had awakened the merchant from his sleep and presented him with a bulky, odd-shaped package. The stranger had left hurriedly, without explanations, and after opening the present, Nordwald had found himself holding an unsightly plaster cast of Villa’s face in death.

Concerned about protecting the gruesome artifact, Nordwald had stored it in a garage, hidden from a public that still considered Villa controversial. Templin’s school, he believed, could show the mask to a discreet audience. Shortly after enrolling Ruth, Nordwald telephoned Templin and promised her the mask. A workman with a crate arrived at her door at about midnight. Delighted, Templin entered the plaster relic in her record book with the notation “Number 1137—Death mask of Pancho Villa—Gift of Otto Nordwald.” She at first kept the mask secreted among her lingerie, but then she moved it to a spot outside her office where it shared a glass case with a mastodon tooth.

An Artist’s Obsession

If you were an illegal alien who had been caught for the fifth time trying to steal across the Rio Grande in the late seventies, you might have ended up in the watercolor class of Steve Beck. The classes were held at La Tuna federal prison, a few miles northwest of El Paso. Beck, a Lincolnesque young man with a master’s degree from Sul Ross University, is a craftsman and painter with a somewhat romantic view of his relationship to Mexico. “I really feel like I’m myself,” he says, “when I’m over there in Mexico.”

In 1978 Beck became artist-in-residence at Radford, where despite an initial dislike for prep-school formalities he was soon appointed head of the art department. From longtime employees he learned about Templin’s unusual collection, which she had left to Radford, and that spring Beck found the mask. He built a sturdy wooden crate for it and began researching its past. He found Templin’s notation “Gift of Otto Nordwald,” but nowhere in the literature about Villa did he find an account of the mask’s origin, although one book reproduces what appears to be an early photograph of the object.

Before long, Beck came up with a plan to put the mask on display, as part of a greater exposition he envisioned in which historians and writers from both sides of the border would convene in El Paso to share creative evaluations of Villa. Beck took his idea to Radford’s director, Phyllis K. Benson, who was interested but said that the school’s budget was prohibitive. Benson wanted to know if, for starters, Beck could produce castings from the mask that could be sold to benefit the school’s art program. Beck agreed to try.

Benson warned him that there had already been a dispute over the mask in Mexico. In 1970, when Mexican president Luís Echeverría took office, he initiated a series of populist measures to ally his regime with the romantic fires of the revolution. One measure was the historical rehabilitation of Villa, whose name was still scorned by the rich and praised by the poor. Echeverría ordered that Villa’s headless corpse be brought to Mexico City for interment in the Monument of the Revolution and that Villa be accorded the full honors of heroism.

Stories about the mask had crept into newspapers in El Paso and Juárez, and a reporter from a Mexico City television program had come to Radford to ask for the mask on behalf of his nation. The school board replied that Radford might sell the mask but would not simply give it away. Two years later, Alejandro Páez Urquidi, then governor of the state of Durango, wrote to the school, making a similar request. “As you know,” the governor’s letter read, “Pancho Villa’s head was cut of [sic] from the body and . . . the death mask is the closest thing to knowing how Pancho Villa really was.” The Durango governor suggested, as an alternative to giving up the mask, that Radford permit a well-known Mexican sculptor to cast a reproduction of it.

The Radford board’s refusal to grant any of the governor’s requests got wide attention from the Mexican press. Ruth Nordwald Graham, the woman whose enrollment at Radford as a child had led her father to entrust the mask to the school, regarded it as a Mexican national treasure, and she asked that it be returned to Mexico. She contended that Otto Nordwald had merely loaned the relic to Radford. She and her brother claimed the mask by right of inheritance.

Given the dispute over the mask, Benson instructed Beck to make his copies secretly. Throughout the winter of 1979 the anxious instructor attended to his academic duties by day and worked in a locked laboratory by night. He rarely slept. One night, while holding the death mask and waiting for a latex coating to dry, the exhausted Beck fell asleep. He had a terrifying dream in which he saw in detail Villa’s mortal ambush at Parral. Gunfire and blood burst into the revolutionary’s eyes, and his vision twisted, dark and red. Beck awakened with a start and lifted his head; he had fallen asleep with his face inside the mask.

Beck arranged to use the kilns of the University of Texas at El Paso for porcelain firing of his castings. As he was crashing imperfect ones against the wall of a kiln one night, an ashen-faced faculty member approached him, warning that someone had called the university and threatened to kill Beck and anyone who aided him. Beck nevertheless exhibited the masks—under armed guard. Few people turned out for the show, though, and it closed after two days.

No one had forgotten the controversy, however. Graham had enlisted the support of former state representative Jim Kaster of El Paso in her campaign to have the original mask returned to Mexico or to her. He relayed her appeal to Governor William P. Clements, who wrote to the director of Radford in January 1980, noting that in February the governor of the state of Chihuahua was scheduled to visit him in Austin. “There will be a great deal of television and newspaper coverage for that occasion. We feel that you should receive suitable publicity for returning this treasure,” Clements suggested. Once again Radford’s board met to consider the troublesome mask, and it decided to keep it. After all, the board reasoned, private schools must survive on their own resources, even artifacts of death.

One night in May 1980, Beck, unable to sleep, found himself sitting beside the Rio Grande, at the foot of Christo Rey Mountain. As he watched a small band of illegal aliens push through the murky waters, he suddenly realized that his obsession had become too intense. He decided to resign from Radford. “I needed some objectivity very badly,” he recalls.

In 1982, after working at other teaching jobs, a refreshed Beck agreed to Benson’s request that he produce a new set of castings from the mask, this time in bronze. Though profits from their sale would go to Radford, Beck took out a personal loan to finance the project. He traveled to Central Texas to work with Lonnie Edwards, a sculptor familiar with metal techniques, and to the Big Bend country to find and process ultra-hard candelilla wax for use in making molds. By April of this year, Beck’s series of Villa masks was ready, he was again making plans for a who-was-Pancho exposition, and he was able to carry out a dream he had nurtured for months. One of Villa’s more important widows, Soledad Saenz, who had lived with Villa at Canutillo, is still alive, in Juárez. Beck and a group of his friends presented her with a casting from the death mask. At first the widow denied that the face was that of her husband, but after she compared it with photos, she changed her mind and thanked the artist. “You have been working in good faith,” she told Beck after he described his plans, “to exhibit a hero of the revolution. You must keep on working.”

While Beck was hunting for candelilla wax in the barren hills of the Big Bend, Ruth Nordwald Graham was readying her claim for court. Last February she filed suit in an El Paso district court, asking that the mask be returned to her family. The case had not come to trial by the summer, when President Reagan announced plans to meet with Mexican president Miguel de la Madrid in El Paso and Juárez. Though the El Paso summit never took place, plans for it touched off new demands that the mask be returned to Mexico. Benson had resigned as director of Radford in June, and she was succeeded by Josefina Salas-Porras, who favored giving the mask to Mexico. The perfect setting for making the presentation, Salas-Porras believed, would be at a dinner scheduled for august, to which she had been invited and which Reagan was to attend. On behalf of Radford she would present the mask to Reagan, who the following day would make it a gift of friendship to De la Madrid.

The new director’s plan was discussed in early August by the Radford board. Opposition carried the day, led by Joe Graves, a history professor at UTEP who insisted on a trade for the mask. The terms of the trade dated back to 1962, when Wallace Miller, a state representative from Houston, made a trip to Mexico. While touring the Chapultepec Castle museum in Mexico City, Miller saw what may be the most sacred object in Texas history, the New Orleans Gray, a flag with golden fringe and black letters reading “First Company of Texas Volunteers” across its front. The New Orleans Gray was the only American flag to survive the Battle of the Alamo. Authenticating it was a note, penned by Mexican general Santa Anna, saying that his troops had captured the flag when the Alamo fell.

Miller talked to the curator at Chapultepec. Would Mexico be willing to trade that historic flag for an object equally important to its past? The curator said that he was interested. Back in Texas, Miller found what he believed was a good trading item. Texas still has the uniform worn by Santa Anna at the battle of San Jacinto, where Mexico lost its rule over Texas. Miller says his offer “went over like dung in a churn. If there is anybody who thinks less of Santa Anna than we do, it’s the Mexicans. He gave away over half of their country, and they don’t want to be reminded of the S.O.B. at all!” Where Miller failed, Graves and the majority of the Radford board hoped to succeed.

But on the border many things, like the revolution, proceed in an uncertain, zigzag way. After refusing to yield the mask in August, Radford’s board agreed in October to return it to Otto Nordwald’s heirs, who plan to give it to Mexico. Meanwhile, a controversy has flared up over who has the legal right to profit from sales of the castings Beck made and paid for.

It is thankless, this business of trading the artifacts of international history, and even more so when the artifact involved is of mysterious origin, associated with a person of dubious character. Accusations can be made on both sides of the border. For instance, last year the U.S. Congress authorized the return to Germany of military artwork seized when Hitler fell. The U.S. asked for nothing in exchange from Germany; why, then, should it demand that Mexico make a trade? Mexicans who advocate the return of the relic wonder, Does the United States place Mexico’s status beneath that of Germany’s? And if Villa’s crimes were horrendous, as American historians assert, why have Americans for so long held on to his death mask? Is it that the gringo must keep his hands on everything, no matter how odious, merely because he believes that everything has a price? Since it is not for love of Villa, the Mexicans reason, then it must be for money that we have kept his death mask on our side of the Rio Grande.

The recent deal between Radford and Nordwald’s heirs promises an end to the skirmishes, but no one will really be satisfied until the mask is actually in Mexico. Whatever happens, Steve Beck plans this spring to open the exhibit that has been his obsession. It will include castings of Villa’s face in porcelain, bronze, and Mexican silver. Scholars and artists from the U.S. and Mexico will come to El Paso to talk about Pancho Villa. No matter what their discussions yield, the head of the old revolutionary will probably rock with laughter, for once again the educated, the rich, and the powerful will be tearing their hair out over him.

Warren Skaaren lives in Austin and is a filmmaker, a writer, and the chairman of the board of FPS, a Dallas film studio. He has recently completed a screenplay about the Gurkhas of Nepal.

Correction: This article originally stated that Villa’s mask was found “more than a century later.” A correction published in Texas Monthly’s Roar of the Crowd, February 1984, indicated it occurred “more than half a century later.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads

- El Paso