This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I’m tired,” Dean Singleton says, stretched out inside his private jet on his way from New York to Denver. His eyes are wide and alert. He does not look a bit tired. “I usually don’t get tired. But I’m tired today.”

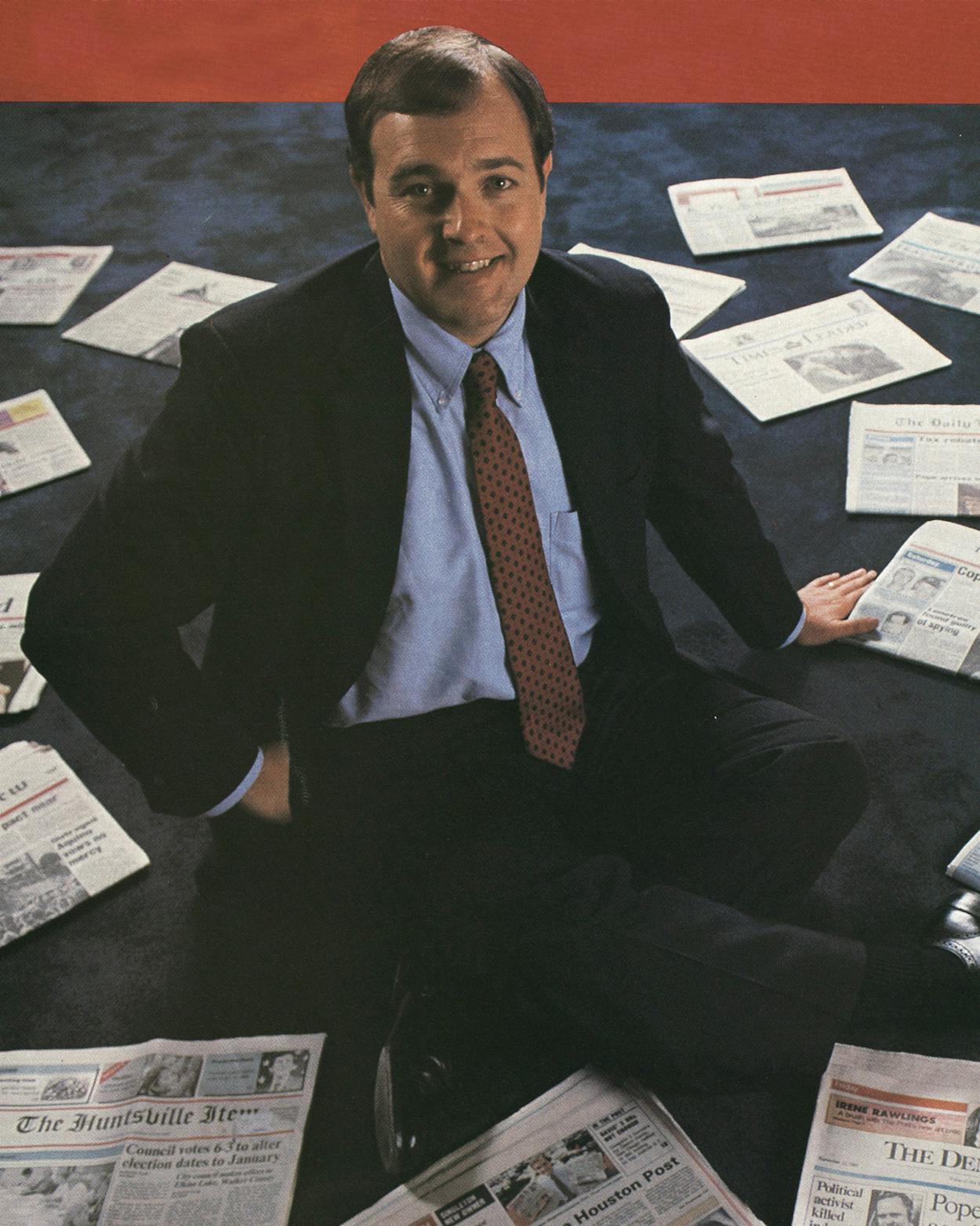

We’re in the preferred CEO interview mode: seated side by side, buttering breakfast rolls at 43,000 feet. It is barely 6 a.m. Moments earlier a round and relatively low-built William Dean Singleton, the newly minted newspaper baron and latest entry in the Most Influential Force in Lone Star Journalism pageant, had arrived at the airport by silver limo.

Maybe he is tired. Within a week Singleton purchased the Houston Post and the Denver Post for a combined $245 million. With those purchases—added to his acquisition of the Dallas Times Herald ($110 million) last year and to the 53 smaller dailies and non-dailies he already owns (9 of those are in Texas)—the 36-year-old Singleton suddenly is the head of an estimated $1.2 billion private company with a combined circulation of 1.3 million, making it the eleventh-largest newspaper group in the country—and rising.

The communications industry has been in a state of percolation over the young entrepreneur. Reporters from Time, Newsweek, USA Today, and the New York Times descended on the lobby of his office in the Times Herald building to answer the inevitable questions about someone who comes out of nowhere: Who is he? What is he trying to do? Can he bring it off? In Singleton’s case the questions were more pointed. Self-promoting headlines—WHO IS THIS DEAN SINGLETON? NATIONAL PRESS WANTS TO KNOW, trumpeted the Times Herald—led reporters to ask if Singleton regarded himself as the Texas incarnation of William Randolph Hearst, who used his newspaper empire as a vehicle to rearrange the world. Along with Wall Street analysts, they also wanted to know why he thinks he can successfully challenge conventional newspaper wisdom, which dictates that second-place papers like the Times Herald and the two Posts are better dead than read.

I descended on Singleton with the rest of them, wanting to learn the same things. But these were not questions I thought about lightly. As a writer at the Dallas Times Herald for nearly six years, I had participated in Texas’ last great newspaper war, which had begun in 1970 with the Times Herald’s purchase by Los Angeles–based Times Mirror Company. A lumbering but deep-pocketed media conglomerate, Times Mirror attempted to kick local journalism out of its dusty provincialism. At its best, the war in Dallas brought national-quality newspapering to Texas. At its worst, the war provided the Dallas papers with a legacy of profound pretensions—which, for papers yearning after the big time, is a start. In Houston, for instance, pretension would be an improvement. But by the time Dean Singleton’s MediaNews Group bought the Times Herald in 1986, the war had been declared over by most observers in favor of the Dallas Morning News.

I wanted to know whether William Dean Singleton, a native Texan and now the owner of newspapers in the state’s two largest cities, is the man to continue raising newspaper standards in Dallas and do the same in Houston. Or is Singleton simply a widget salesman whose widgets happen to be newspapers, a man whose cold business strategies once earned him notices as the inventor of survival journalism? And if Dean Singleton merely keeps the second-place newspapers in the state’s two biggest markets alive, given Texas’ current woes, is that as much as we should ask?

Within 24 hours of the announcement of Singleton’s purchase of the Dallas Times Herald in June 1986, a high-ranking editor summoned me to his office and asked me to close the door. He then informed me that the conversation we were about to have would not be taking place. He lit a cigarette and told me to find another job as soon as possible. He said that what was about to happen at the Times Herald under Singleton’s ownership would not be pretty. The paper would be reduced to a rag, he predicted, whose ethics, politics, and disdain for its writers would be the shame of the industry.

That was only one example of the paranoia that swept through the Times Herald after Singleton announced his purchase. Editorial staffers resigned by the dozens; by the time he took control in September, the paper’s long distance bills had been increasing for months as reporters and editors looked for jobs. The operative nickname among Times Herald reporters for Singleton and his gang of cost-cutters was “the flesh eaters.” The phrase was coined by the staff at the Trenton (New Jersey) Times when Singleton moved in to run the paper bought by a Washington financier in 1981. Reporters at the Times Herald who had worked in Trenton advised peers to get fired in the first round of layoffs, because the severance pay would be better than during the second and third rounds, which they assured would follow. We heard the fate of a business writer who had been axed his first day on the job in Trenton when he added to a press release by a major advertiser that its parent company had filed for Chapter 11.

Things did not improve once Singleton arrived in Dallas. Five days after he moved in, 109 people were laid off. The editorial page editor was booted and a new one hired with the publicly stated goal of being “pro business.” To the staff, the mandate of toadyism was being made clear. Running gags centered on a biography of Singleton that had appeared in the paper’s in-house magazine. It told of Singleton’s days as a poor boy growing up in Graham, how he had once been turned down for a job at the Times Herald (he later got one as a copy editor at the Morning News), and then how by pluck and by luck he finally returned to own the paper that once would not hire him.

It’s not the money,” Dean Singleton says, his hands moving from the rolls to the fruit on the tray in front of him. I have asked him to explain what has driven him to build what can now be called an empire. Singleton reaches back into his past. “When my father turned sixty-five in 1982, times were getting bad in the oil patch. My father worked in the field for a small oil company, and in September they told him that they were going to retire him in October. They told him on a Friday night.

“That Monday he had a heart attack. My mother rushed him to a hospital. He said he didn’t want to leave the hospital—that he wanted to work till he died. That afternoon he was dead.”

Singleton takes a breath. “In the casket later my father had a smile on his face. It was as though he were saying, ‘I showed those bastards. I didn’t retire.’

“Well,” Singleton adds, his blue eyes steely in the weak morning light, “I’m not going to retire either.”

His point seems to be that he isn’t about to entrust his fate to someone else. He is going to get bigger and bigger until at last he is in charge of his own destiny. I think about pointing out that as big as Times Mirror is, it couldn’t control its own destiny, at least not in Dallas. But by that time, Singleton is well into the story of how he grew up in a leased four-room farmhouse outside of Graham, a dry little town in North Texas. One of Singleton’s earliest memories is of his parents’ worried discussions each month about scaring up their $40 rent. By the age of five, Singleton was daydreaming about being a businessman, for no other reason than that he’d seen the spoils from a seven-day-a-week, fourteen-hour-a-day oil-field pumper’s life and reasoned he wanted more.

But much as his upbringing taught Singleton the value of money, it also taught him the value of credit. Singleton’s parents had credit at several businesses in town and juggled their debts from one to the other in hopes that each month it all would come out even. The maneuvering was not lost on young Dean. When he was eight he sold Christmas cards supplied by a company in New York and reeled in customers with an offer that they could pay him after delivery. But the company required full payment before it would provide the cards. Singleton wrote the company an eight-year-old’s letter promising payment after delivery, received the shipment, distributed the cards, then mailed the money back to New York, minus his profit. By twelve, when he didn’t have enough money to raise pigs for a 4-H fair, Singleton persuaded a local banker to loan him $100 for the pigs and talked a supplier into fronting him the feed. He then raised the pigs, sold them, paid his debts, and again kept his profit.

Singleton’s ability to borrow, delay his debt, bank “on the come,” and make a profit is the cornerstone of his newspaper business. The devices he uses now to obtain capital, he says, are not far removed from those he used to raise pigs.

His early success gave him a self-confidence that remains intact. “I am surprised at what he’s accomplished,” said a classmate from Graham. “But I’m not surprised that he tried to do it.”

From the age of fourteen until he graduated from high school, most of Singleton’s after-school hours were taken up by work at the Graham News. He became consumed by the paper, excited by the action that ran from the newsroom to the back shop and the sales staff. “I just liked hanging around newspapers,” he says. “Somebody was always there, something was always going on.” After bumping around several colleges (he never received a degree) and working at mostly small newspapers—with a brief stint at the Dallas Morning News—Singleton decided in 1972, at 21, to start his own paper.

He joined a partnership that founded a semiweekly in the tiny Panhandle town of Clarendon, where residents clamored for an alternative to the existing amateurish-looking paper. Singleton became a half partner in return for working as publisher, editor, writer, salesman, and whatever else a day called for. Within six months the competing paper folded.

Singleton married the daughter of a prominent family, became friends with well-to-do businessmen, and raised his sights beyond the Clarendon city limits. In 1974 he and his partners bought three more weeklies near Fort Worth. They all boomed. “When I had a weekly, I just wanted to have a daily,” Singleton says of his ambition at the time.

Then in 1975 Singleton, leading another group of investors, bought a daily, the Fort Worth Press, from the ScrippsHoward chain, which had stopped publication of the paper two months earlier. He immediately moved into a hotel across the street and went to work day and night.

But his efforts earned him ridicule from his staff. They later told of memos urging reporters to shop at a department store that ran coupons in the paper, of publishing syndicated columns to which the competing Fort Worth Star-Telegram owned the rights, of editorializing against eight proposed constitutional amendments and then, a few days later, editorializing for the same amendments. When the paper closed on November 6, 1975, 88 days after it had reopened, a Fort Worth constable told reporters, “I have yet to find a single person who will admit to being the owner of the Fort Worth Press.”

Singleton says that he learned a valuable lesson: “You can’t really know what success is unless you’ve tasted defeat. I learned that I never wanted to taste it again.”

The mess in Fort Worth had personal as well as financial consequences for Singleton. He has always had a surreal capacity for work—he would often spend twenty-hour days on the job in Clarendon. As the Press collapsed, though, so did Singleton’s marriage, almost entirely, he says, because of his blind dedication to work.

But his divorce, while painful, taught Singleton that he was incapable of reordering his priorities. His second wife, Adrienne, to whom he has been married for almost three years and with whom he has a 21-month-old son, acknowledges that it is clear Singleton’s marriage to his job comes first. “I tell him I always wanted to be the other woman,” she says in the library of the couple’s Tudor house in North Dallas, “so I could have the best of both worlds.” She echoes the sentiments of others close to Singleton when she observes that he is exactly what he appears to be: an ambitious young man who believes that trying harder than anyone else will bring rewards. “Dean’s really not very complex,” she says.

Besides the capacity for marathon work hours, there has been another key to Singleton’s success: his knack for friendships with businessmen twice his age, who admired and trusted him, often after a single meeting. These friendships have aspects of working relationships between fathers and sons and point to a remarkable quality in Singleton. The quality of his mentioned most by these men is self-confidence.

The friendships began with Joe Donohue, now a 73-year-old insurance executive in Massachusetts who hired Singleton following the shutdown of the Press to save his own ailing string of weeklies. Donohue says Singleton turned the papers around three months after he arrived. He now phones Singleton every Sunday morning without fail.

Singleton left Donohue three months later to work for Joe Allbritton, a financier from Houston who now at 62 heads the Riggs National Bank in Washington, D.C., and owns several TV stations. Allbritton’s reputation as a financier already had been secured in Washington, in part by his ownership of the Washington Star, when he hired 25-year-old Singleton to acquire and operate newspapers for him.

The association with Allbritton was Singleton’s biggest break. Allbritton threw the doors to high finance wide open for him. “Dean had access to very sophisticated people on a daily basis,” says Howell Begle, a former Allbritton attorney who now represents Singleton. “Those people collectively had a fundamental impact on Dean to help round him out from crackerjack operator to someone sophisticated in such things as capital markets.”

Singleton ran eight papers for Allbritton, each a Rust Belt money-loser when it was bought but profitable afterward. During this period the term “survival journalism” was coined. On one hand, survival journalism as executed by Singleton—massive layoffs and cinched budgets—makes economic sense, particularly in light of the alternative, which is to shut down.

On the other hand, the danger of that kind of operation, in the view of many newspaper people, is that the resulting newspaper is not worth reading. “The newspaper Joe Allbritton now owns in Trenton is only a shell of the paper Singleton praised so highly,” went a Columbia Journalism Review story a year after the purchase of the Times. “The newspaper’s integrity has been challenged by repeated accusations that the Allbritton team will bend over backward to please advertisers.”

Singleton’s alliance with Allbritton also gave him an introduction to big numbers. In 1982 he negotiated for Allbritton a $354 million option to buy the New York Daily News, the country’s largest daily newspaper. Among the bidders Singleton outmaneuvered was New York real estate mogul Donald Trump. The option eventually was nixed by Allbritton.

Singleton left Allbritton in 1983 to form his current partnership with Richard Scudder, now 74, a third-generation newspaper owner from Newark, New Jersey. The two met when Singleton attempted to restructure the debt one of Allbritton’s New Jersey newspapers owed to Scudder’s newsprint company. Singleton persuaded Scudder to supply the paper with newsprint in return for payment from the paper’s future profits, which started rolling in several months after Singleton took over. As an inducement, Singleton offered to pay for a ton and a third of newsprint for every ton he purchased. Singleton and Scudder had lunch together each week afterward, discussing, Scudder says, “what fun it would be to go into the newspaper business together.” Scudder now is the key player with Singleton in MediaNews Group.

Scudder is the one in the partnership who at the beginning had real money, some of it inherited, a lot of it gained through the patent he owns on a process to recycle newsprint. Singleton’s first newspaper acquisition with Scudder was the Gloucester (New Jersey) County Times, in suburban Philadelphia. They then bought several small papers with no thought, Scudder says, “to get into it the way we have.”

In 1985, through Scudder’s long friendship with Floyd Sparks, another newspaper owner, Scudder and Singleton were offered Sparks’s chain of four prime mid-sized dailies outside of San Francisco. They didn’t have nearly enough money. So Scudder approached Media General, a media conglomerate to which he had sold his family’s Newark News, and persuaded it to put up the equity capital for a 40 percent interest in the Sparks newspapers.

MediaNews took off after that, buying four other small papers, in addition to the California dailies, within six weeks. More small acquisitions followed, some with profits as high as 40 percent of revenues. So by the time Singleton approached Times Mirror about the Dallas Times Herald, he may have been an unknown, but he was an unknown with clout.

By 1986 Times Mirror had grown weary of the losing battle its Times Herald was fighting with the Morning News. The Times Herald had gone through four publishers in nine years, and it was trailing badly in both circulation and advertising. Survival journalism tactics, which might have helped the balance sheet, were not the company’s style. Times Mirror accepted Singleton’s offer of $110 million, a price that analysts viewed as a steal for Singleton, since the land and physical plant alone were almost worth the purchase price.

Even so, the prospect of years of red ink scared off one potential Singleton partner. Media General, a public company, unlike Singleton’s privately held MediaNews, chose not to participate in the Times Herald deal. Instead, Singleton used his partnership with Scudder, in which the split was sixty-forty, in favor of the older man. Under their arrangement, MediaNews provided the $50 million down payment, and the rest was financed through banks and Times Mirror. As usual, Dean Singleton put up none of his own money; in 1983 he had borrowed $200,000 from Scudder and has not invested in MediaNews since.

The same Singleton-Scudder partnership was behind the purchase of the Houston Post from Toronto Sun Publishing, which had bought the Post four years earlier from the Hobby family interests. Singleton’s offer of $150 million was not the best cash deal the Canadians could have taken, but Singleton threw in an extra inducement that was reminiscent of his old newsprint deal with Scudder. If the Post’s 1992 gross revenues are more than $40 million above 1987 gross revenues, Singleton will pay the Sun $1.25 for each $1 of increase. In effect, Singleton has a five-year 25 percent balloon note, except that he has to pay it off only if the Post is doing better than it is now. A lot of Texas oilmen wish they had such a deal. With the acquisition of the Post, Singleton plans to offer advertisers lower rates for buying space in both papers. But this competitive advantage is offset by his heavy dependence on the slump-ridden Texas economy—too heavy, according to some analysts.

I’m not a king maker,” Singleton tells me, not far from Denver. “I’m not really that interested in politics. I’m interested in having a good state, and I’ll campaign for what’s good for Texas. Our papers will endorse candidates. But they won’t back them, won’t slant coverage toward them.

“In Dallas last year the editorial board voted ten to one to endorse Mark White. I was the one for Clements. The Dallas Times Herald endorsed White.” Singleton smiles. “And I was wrong.

“I think that sent a message to the staff that their influence would be the same as it always has been. Once the Houston sale is complete, I simply see myself as head of the best and most prominent newspaper organization in the state.”

If Singleton has a king maker’s agenda, he has certainly not made it apparent, either inside or outside his organization. He did meet with Dallas business leaders shortly after buying the Times Herald and told the group that he was pro-business, but one onlooker, a representative of the Hunt interests, came away instead with the feeling that Singleton was anti-establishment. “He doesn’t like unions, and he doesn’t like big corporations,” says the onlooker. “He likes entrepreneurs. And he’s as tough as nails.”

Within the industry Singleton, with his pack of second-place newspapers, is still seen as a man swimming upstream. But Singleton says his risks are not as large as they seem. First of all, he says, none of his recent major purchases were in danger of closing when he bought them. The Dallas Times Herald had showed its first losing quarter after years of profitability when Singleton bought in, the Canadians had made some money in Houston, and the Denver Post leads its competitor in Sunday circulation. Singleton also says that none of his purchases are bet-the-ranch purchases, that his company is large enough to absorb a substantial loss, and that in most cases the assets he purchased (real estate, new presses) are near to or exceed the total prices he has paid. “If any of our recent acquisitions didn’t work out, it wouldn’t have much effect on the company financially,” Singleton says. “The damage would be all psychic. We’ve never had a failure.”

Given that, the mood is upbeat in Houston. Toronto Sun Publishing already had made the sort of staffing cuts at the Post that Singleton has become famous for, so people there see Singleton as a potential savior. “The Post is like a death row inmate who’s gotten a reprieve,” says one observer. “Now they’re waiting for the commutation of their sentence.”

Those looking for clues to the future under Singleton are finally left to read his past, particularly his year at the Dallas Times Herald, his only tested big league venture. There his reviews have been mixed. Certainly the mood at the Times Herald has improved since the early days of Singleton’s ownership. The worst-case scenarios that had theater critics doubling at city hall and furniture ads splashed across the front page have not materialized. Staff levels are up, and the paper has run some first-rate stories about the savings and loan crisis. Singleton admits that he has “grown up” since his days in Fort Worth and Trenton.

But he hasn’t lost his will to fight; the kind of gentlemanly swordplay that once characterized the competition in Dallas has already been replaced with brass knuckles. Bright graphics, loud headlines, and front-page stories on why women’s clothing costs more to launder than men’s have remade the Times Herald so that it can no longer be confused even accidentally with the stolid, sometimes somnolent Dallas Morning News. Still, the Times Herald’s incessant self-promotion often makes staffers grimace. On the day the Times Herald announced Singleton’s acquisition of the Post, the paper ran a front-page box on the size of media companies, listing the top twelve (Singleton’s is eleventh) and number 34—A. H. Belo, the owner of the Morning News. Singleton also has filed a suit against the Morning News, claiming that it has been cooking its circulation figures. He is expected to do something similar to the Chronicle in Houston. He has already fired the first shot at the Chronicle with a front-page banner announcing TEXAS PUBLISHER BUYS THE HOUSTON POST—a slap at the Chronicle’s absentee Hearst owners.

There is no single editorial formula to a Singleton paper beyond a kind of reader friendliness. He once said of his philosophy, “A newspaper is a product, like a candy bar. You have to package it to be attractive to the reader. You have to put in the ingredients they want.” Singleton is a great believer in chamber of commerce journalism—covering events and announcements intended to boost civic pride—and believes that if a newspaper gives a community enough support, a community will return that support when the newspaper confronts it with a tough look at the tough issues.

While Singleton’s group has yet to generate a reputation for journalistic distinction, it has earned one for keeping journalists alive. Too many second-place papers have died in the last decade—there now are only 20 two-paper markets left in an industry of 1,657 newspapers. Singleton’s reputation is sure to grow. No one associated with Singleton can imagine him slowing down, and attorney Howell Begle says that the investment firm of Drexel, Burnham, Lambert is talking about raising “incredible” sums for future Singleton acquisitions. He has also considered other partnerships to purchase other papers. At one point I ask Singleton if he regrets not ever getting to buy the New York Daily News. Singleton gives me his amused smile and replies, “I haven’t not ever bought it yet.”

A few miles from Denver Singleton shifts in his seat. He is peering out his window, visibly energized by what he sees below. “I love these markets,” he says out loud to himself. “Denver, Houston, Dallas—I love these markets.”

His plane lands a minute later. Singleton is greeted at the airport by a woman who will drive him downtown to his new paper. He is scheduled to meet first with the Post’s unions, then with its management, and then to pay what he calls a courtesy call on the president of his new competitor. As Singleton leaves the terminal his attention is caught by a newspaper rack. He walks over to it, drops in a coin, and buys a paper.

This one cost Singleton a quarter. He paid cash.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Houston

- Dallas