Everyone who has written about José Cisneros, the legendary historian and illustrator of the Spanish Southwest, has remarked on his excessive modesty and almost painful shyness. Indeed, at our first meeting in his tidy El Paso home, he admitted that he is a nervous wreck every time he appears in public. He recalled in particular the evening in 1985 when he received the Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame for his landmark collection of illustrated horsemen, Riders Across the Centuries (1984). “I was afraid they’d find out I’ve never been on a ranch or ridden a horse,” he said, in a bilingual deadpan. “But then, I illustrated a book on Ireland and I’ve never been there either.” Shy and modest he may be, but after nearly a century of making up life as he encounters it, José Cisneros has his act down pat.

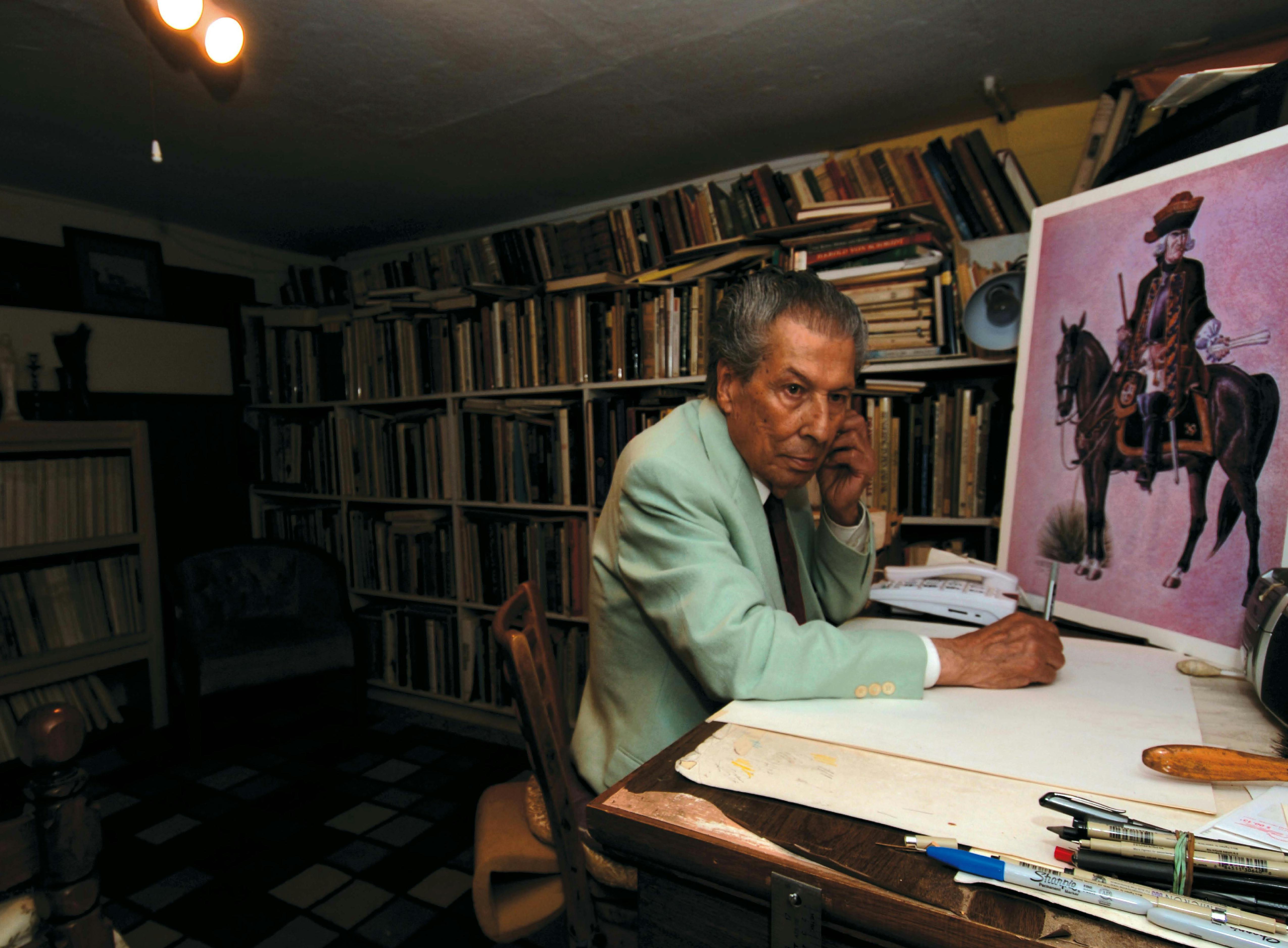

Though almost blind and nearly deaf, the 96-year-old artist bounced with great enthusiasm from room to room, showing me hundreds of books and magazines containing his drawings, as well as scrapbooks of original sketches, so physically and mentally agile that I had to scramble to keep up with him. He moved like a good middleweight, dapper and confident in a pink dress shirt, gray flannel trousers, and white sneakers, his silver hair brushed back Cesar Romero-style. Skipping down the steep flight of stairs to his basement studio, he talked about his “gray period,” the last hurrah of a long career. He showed me an unfinished black and white drawing, tentatively titled “Lower Valley Pioneers,” and confessed he wasn’t happy with its progress.

Art historian Paul Rossi has called Cisneros the country’s leading authority on “the horsemen of Spanish American history,” and a visit to his tiny studio shows why. The room was jammed to the ceiling with books on heraldry; calligraphy; Mexican, South American, and Southwestern history; horses and horsemen; the gauchos of Argentina; a three-volume encyclopedia on bullfighting; and even a book titled Wine, Women, Toros. When he worked for El Paso City Lines, first cleaning and later painting buses and electric streetcars, Cisneros used his knowledge of heraldry to accurately paint the coats of arms of Mexican states on the sides of city vehicles. No historical detail escapes his attention, as John O. West explains in his biography José Cisneros—An Artist’s Journey. While working on Riders Across the Centuries, Cisneros figured out which parts of the horsemen’s costumes had prevailed over time. He noticed that it was fashionable for seventeenth-century French horsemen to wear ruffles at the bottom of their drawers, and the fad later spread to Latin American countries such as Argentina and Mexico, where some Indian tribes still wear lace drawers.

There wasn’t much furniture in the studio—just a small bed and a desk. Mounted on top of the desk was an enlargement machine that magnifies images one hundred times and projects them on a screen. It was a gift from Laura Bush and friends, their way of encouraging Cisneros to keep working even as his sight failed. There were Bush family photos and mementos all over the house. A photograph of George H. W. Bush was signed “To my esteemed friend José Cisneros whose art has brightened our life.” In a ceremony at the White House in 2002, George W. Bush awarded Cisneros a National Humanities Medal, the nearest thing to knighthood we have in this country (Cisneros was knighted for real in 1991 by Juan Carlos I, king of Spain). He told me that Laura held his hand during the entire ceremony. “At least according to the Washington Post,” he added with a smile.

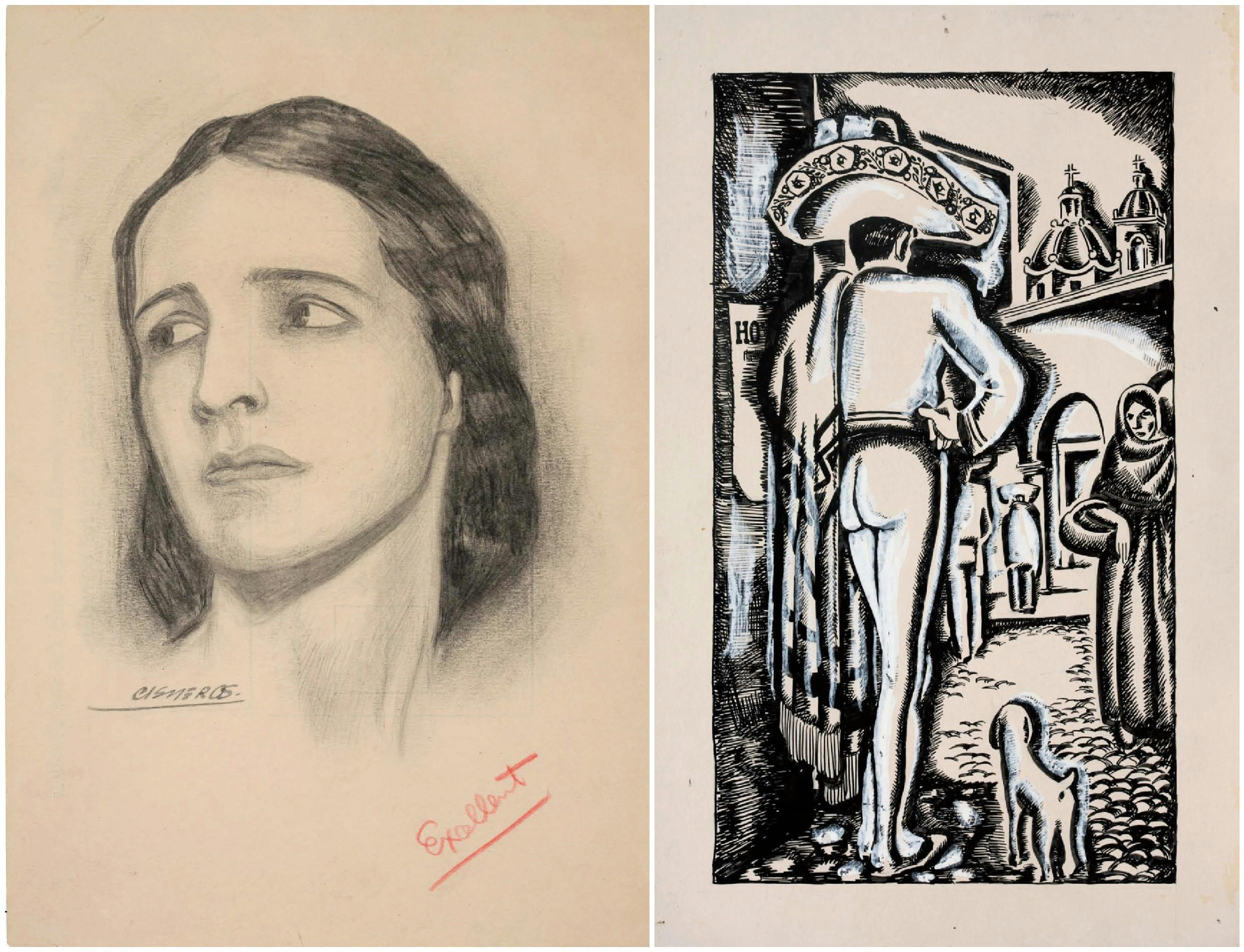

“A few of the early pictures were reproduced in John West’s biography,” said Adair Margo, one of Cisneros’s greatest patrons and admirers. “But we didn’t have a clue that others had survived. We never dreamed we’d have an opportunity to show drawings Cisneros did when he lived in Mexico.”

Cisneros was born in 1910 in Ocampo, a small village in the Mexican state of Durango. The earliest of the drawings in Margo’s exhibition was made when he was twelve. It is titled Dorado and depicts a storybook version of the house and fenced compound where the family lived after fleeing their native village during the Mexican Revolution. “It was a hard trip,” Cisneros recalled, “because there was a snowstorm and we were still barefooted.” Cisneros taught himself to read, memorizing the sounds of letters and their combinations from a phonetic primer. He had already begun doing crude drawings, which his family dismissed as doodles. In 1925 the family moved north to Juárez. Cisneros got a student passport to attend the Lydia Patterson Institute, in El Paso, where he learned English and pursued his lifelong obsession with Mexican and Southwestern history. Drawing came naturally to Cisneros, but drawing materials were precious. He drew on scraps of paper, modeling his work on pictures he found in movie magazines and newspapers. Two of his early works are highly stylized portraits of Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. But there are also profiles of Mexican peasants and lovers and soldiers, of street scenes in Juárez that poke fun at naive tourists who seem to see bullfighters and banditos on every corner. Humor is one of Cisneros’s more endearing trademarks: In many of his drawings a scrawny dog trots alongside a richly costumed horseman mounted on a sleek, fat steed.

In 1930 Cisneros was forced to quit school and take a job delivering groceries in El Paso for $5 a week. Since the international bridge closed at midnight, it was often impossible for him to get back home to Juárez, so he’d sleep on the south El Paso streets. Seventy-six years later, he still recalls the sounds and smells of the characters he encountered in that neighborhood by the bridge—the retarded man who traded gummy candy for used bottles, the immigration inspectors who forced Cisneros to strip naked and sprayed him down with scalding water, Simon the Sweet Potato Man. At night he drew borderland scenes, a few of which were published without pay by small Mexican journals, usually to illustrate some writer’s work. His one and only art lesson came from an itinerant painter who worked out of a little shack and charged students 25 cents an hour. The lesson was straight-forward: Discovering that Cisneros was color-blind, the painter advised him to give up art and seek a career as a bricklayer.

Instead, Cisneros found work as a window dresser at the White House Department Store, in El Paso, where he used the backs of old posters as art paper, finding that when he scratched the surface of the poster board with his pen, ink spread in interesting ways. Years later he learned that someone had developed a material called scratchboard for that exact purpose. Slowly, his reputation in Juárez grew. He became a member of Arteneo Fronterizo, a local organization of artists, poets, and authors. But Cisneros was unknown across the river until 1937, when he worked up the nerve to introduce himself to the famous painter and writer Tom Lea. At this point, Cisneros was painting buses, and Lea, whose father was the mayor of El Paso from 1915 to 1917, was painting a mural on the walls of a federal building. But when Cisneros approached him with a portfolio under his arm, Lea was impressed with the young Mexican artist’s distinctive crosshatch style and authentic take on border culture, telling him, “You are depicting the history of your own people.” He tore off a piece of tracing paper and wrote a note introducing Cisneros to the director of the El Paso Public Library and advising her that “this fellow has some stuff.” The director agreed, arranging Cisneros’s first exhibit in the United States. This led to another public showing, in Juárez, and, a year later, to Cisneros’s first sale, to a magazine in Mexico. But the sale netted only a few bucks, and Cisneros had to keep his job as a bus painter. The international streetcars used in the forties by the El Paso-Juárez line were probably the most colorful in the world.

After some haggling, Cisneros got a leave of absence from El Paso City Lines and made the long trip to Austin with his wife, Vicenta, one of their five daughters, and a granddaughter. Vicenta, who died in 1994, often worked beside her color-blind husband, directing him as he applied colors to his black and white drawings of seventeenth-century noblemen, missionaries, and other pompous borderland characters. While in residence at Paisano, Cisneros would often spend days doing research at the Institute of Texan Cultures, in San Antonio, then return home to draw in the evenings. The project ultimately consumed more than a decade.

In 1984 Texas Western Press published the first edition of Riders Across the Centuries. In the forward to his book, Cisneros writes that the first Spanish horses were responsible for bringing civilization to our continent and that he considers it his mission to “follow their hoofprints along and across the land … to restore, visualize and depict the physical appearance of their riders …” Ironically, the Southwest’s greatest illustrator of horses has claimed that he never saw one except in pictures until Tom Lea introduced him to an El Paso rancher named Ray Bell. Can a boy really grow up in rural Mexico without seeing a horse? Cisneros has said that his mother’s family was full of vaqueros. When I asked about the contradiction, the artist didn’t appear to hear the question. Maybe what he means is that he never saw a horse through the eyes of an artist until later in life.

Like all of us, Cisneros’s take on history is influenced by those who made his career possible—the bankers, politicians, and scholars, the government, military, and establishment figures who supported him. This may explain why, with a few exceptions, the conquistadors in his drawings never appear as bloodthirsty ghouls, as they do, for example, in the murals of the great Mexican artist Diego Rivera, an avowed Communist. Cisneros has charged that “Diego distorted his figures as much as he distorted Mexican history.” In his long career, however, Cisneros has occasionally succumbed to historical distortions, in the pay of partisans. When former attorney general Will Wilson led Big Oil’s charge to get the Supreme Court to declare Texas’s coastal tidelands the property of the state rather than the federal government, Cisneros was commissioned by an aide of Wilson’s to do a series of drawings propagandizing the Texas claims. One drawing, titled No Man’s Land, addressed a side issue, suggesting that eight contested oil fields on the Texas-Louisiana border rightfully belonged to the Lone Star State.

Currently, Cisneros is an indirect participant in an El Paso controversy revolving around a gigantic equestrian statue of Don Juan de Oñate, the first Spaniard to explore the Pass of the North and one of Cisneros’s great heroes. The sculptor, John Houser, is a friend and colleague who spent a lot of time at Cisneros’s house, planning the project. He completed the work earlier this year, but protestors demanded that Houser cut off Oñate’s feet, as Oñate had the feet of rebellious Acoma Indians. (In October the statue was erected at the El Paso International Airport, with feet.) Cisneros has written that Cortés’s men were “a hardy, adventurous and unruly crowd.” When I suggested that some tend to look on them as butchers and tyrants, he dismissed the criticism with a wave of his hand. “The way I look at it,” he told me, “the early Spanish left their homes to come to a place where there were no roads, no comforts, herding cattle and chickens, enduring great hardship and personal risk. I respect that.”

The conquistadors in Cisneros’s drawings appear determined and often arrogant, clad in the comically gaudy costumes of the times—chain mail coats, goofy helmets, swords, lances, and heavy leather shields—meticulously drawn uniforms that impress the chauvinism of medieval times on our imaginations. The level of period detail in these depictions is breathtaking: Historians cite his drawing of the obscure cuera dragoons, Spanish cavalrymen who protected the missions of Texas from hostile Indians in the eighteenth century, as an example of his untiring scholarship. For me, though, the true brilliance of his work comes alive in the rippling inner fire of the dancing, prancing, rearing horses, their eyes flashing fear, urgency, and grace and their demeanor betraying the hopelessness of their task.

One hundred of Cisneros’s horsemen now hang on the fourth floor of the library of the University of Texas at El Paso. I wonder what the students think of the drawings. I wanted to ask, but on the day I visited, the only students I saw were napping on the benches provided for art fanciers. I think they must see a reflection of themselves in the illustrations, a reaffirmation of the three cultures that came together in this historic pass and an acknowledgement that it wouldn’t have happened without the horse. Nor could we have understood or appreciated the gravity of our heritage without an artist as gifted as José Cisneros.

In West’s biography, there is a brief passage that says it all. A student stops Cisneros near his artworks in the hallway of the UTEP library and asks, “How long did it take you to do all those drawings?” Cisneros must have smiled when he replied: “All my life.”