By 2018, humans have managed to create a polio vaccine, invent the wheel, pen poetry that has transcended centuries, construct great walls and 2,000-foot skyscrapers, land several men on a distant rock floating in space, and touch the stars.

But despite all of our accomplishments, there is one thing that we cannot understand or master: the inevitability of death.

Death is the same for everyone. It doesn’t matter if you’re Mark White, who was once one of the most powerful men in Texas, or Henry Lewis, the unofficial fishing guide for Caddo Lake in the tiny East Texas town of Uncertain. The different lives we lived all merge at the same distant point.

It’s how we arrive at that point that—for all of our innovations—continues to elude and frustrate us. In 2017, 26 people were killed after a gunman opened fire inside the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, and 88 were confirmed dead after Hurricane Harvey barreled through Texas. An act of terror and an act of God—two more things that are, for the most part, out of our control. We don’t know how to stop these large-scale losses. We don’t know how to stop cancer. We don’t know how to stop death.

But we do know how to mourn, to clutch fading memories and hold them close. We know how to honor a lifetime of stories and experiences, an unmeasurable storage of knowledge and perspectives that can never be replaced as somehow we move forward without the people we have lost.

We know not only how to miss them, but to keep part of them with us. Here are some of the Texans who left us last year.

Skip Fletcher

February 12, 1934—January 31, 2017

Doctors might say that a steady diet of corn dogs is a sure way to an early grave, but Skip Fletcher, the State Fair of Texas’s Corny Dog King, grew up in a corn dog dynasty and somehow lived to the ripe age of 82. As his parents perfected the Fletcher’s dog recipe in their family kitchen, a young Skip was the “chief taste taster,” he once told the Dallas Morning News. “My mother didn’t cook a meal in the kitchen for three months,” Fletcher once recalled. “We were taste-testing corny dogs!”

For most Texans, Fletcher’s Corny Dogs are better known as a once-a-year treat. Skip’s father and uncle first launched the deep-fried hot dogs speared on a stick at the state fair in 1942, when they cost just fifteen cents each. Skip and his brother Bill eventually took over the family business in the late 1980s, and the company now sells 600,000 corny dogs a year at the State Fair of Texas alone. Under Fletcher’s leadership, the business even ventured into groundbreaking territory (for corn dogs, at least), when he unveiled a vegetarian corny dog in 2015.

Fletcher’s Corny Dogs are internationally renowned. According to the Morning News, they’ve been featured in the New York Times and on the Travel Channel, and have graced the gullets of everyone from Mikhail Gorbachev to Oprah Winfrey. Fletcher died just before the corny dog stand celebrated its 75th year at the state fair, but we’re willing to bet it’ll be there for 75 more.

Lyda Ann Thomas

November 20, 1936—April 19, 2017

For generational Galvestonians, calm in the face of the storm is an inherited trait. Or at least it was for Lyda Ann Thomas, the coastal city’s mayor from 2004 to 2010. Her grandfather, I.H. Kempner, helped finance the construction of the Galveston Seawall and the raising of the island after the devastating 1900 hurricane. He too served as mayor, in 1917, nearly a century before Thomas was elected to the same role. Like her grandfather, Thomas would eventually become the city’s hurricane savior.

She shepherded Galveston through two of Texas’s biggest storms, Hurricanes Rita and Ike. Her poise and serious-but-unsensational public addresses saved countless lives, earning her the unofficial title of Galveston’s “Hurricane Mayor.”

In 2005, with Hurricane Rita barreling toward the Gulf Coast, the islanders were worried. Horrific images from New Orleans, where weeks earlier the local government badly failed to protect its people from the destruction of Hurricane Katrina, were still fresh in everyone’s mind. “I think we were overwhelmed,” Thomas later told the Galveston Daily News. “In my mind’s eye all I could see was Galveston in 1900 and New Orleans in 2005. I had to make a decision right then and there that the fear could not show.” She appeared on national television broadcasts, including “The Today Show” and CNN, and asked Galvestonians to leave the city ahead of the storm. Though she was upfront about the storm’s very serious threat, she spoke without even the slightest hint of panic in her voice. “The news is not good,” she told the cameras. ”We’re into an extremely dangerous period.” Many residents—particularly the poor and the disabled—heeded her warnings, and were successfully evacuated in an orderly fashion by buses operated by the city and Galveston ISD.

Rita never really unleashed on Galveston the devastation that forecasters predicted. But in nearby Houston, the evacuation process was so panicked and disorganized that about 100 people died, not from the storm, but instead from the stifling heat while stuck on the region’s jam-packed highways. That city’s response to the incoming storm became a tragic and textbook example of what not to do. Thomas, meanwhile, was celebrated for her response, making her a model for mayors in times of crisis.

The Galveston Daily News later published an editorial, praising Thomas for her actions: “During those tense moments Thomas did at least two critically important things: She was honest about how dangerous the situation was. She looked people in the eye and in a memorable phrase told them that the news was not good and that everyone was going to have to take action. She did not show fear. Instead she calmly outlined plans to get people off the island.” In 2007, the newspaper gave her its Citizen of the Year award.

Three years later, Galveston would once again be tested by a major storm: Hurricane Ike, which made landfall with devastating strength. Once again, Thomas would be there for her city. With the chaos caused by the evacuations in Houston before Rita still lingering in her head, Thomas reluctantly ordered the evacuation of Galveston three days before Ike hit. It was the right call—70 percent of Galveston’s buildings would be damaged in the storm. “She never wavered and she never lost her cool,” Mary Jo Naschke, city spokeswoman during Hurricane Ike and a friend of Thomas, later told the Houston Chronicle. “Every time she came under fire I was right there… She listened before she talked, she measured what she said.”

Thomas passed away in April, at the age of 80, just a few months before Hurricane Harvey battered the Texas coast, including Galveston. As we move forward in this uncertain age of destructive weather, with 100-year storms becoming all too frequent, the lessons from Thomas’s leadership through such crises are perhaps more valuable than ever.

Henry Lewis

June 3, 1938—May 8, 2017

More often than not, the local legends we love never capture national attention, but Henry Lewis helped put Uncertain, Texas, on the map before he died. The 78-year-old star of Uncertain, a documentary released in 2015 about the tiny East Texas town that consisted, as Texas Monthly‘s Wes Ferguson wrote last year, “of 94 bayou folk, retirees, and reputed outlaws,” hardly lived long enough to truly bask in his newfound big-screen fame.

Lewis lived “up the hill” from the marina in Uncertain, in the Texas swamplands just across from the Louisiana line. He was the unofficial fishing guide at the town’s Caddo Lake. In the film, Lewis’s quiet drawl required subtitles as he told the tales of an old man who lived a long and complicated life. “I know I’ve done wrong,” he said in the movie, “but I know I’ve done good. And I pray to God that my goodness outweighs my wrong.”

And certainly, Lewis wasn’t exaggerating about his wrongs—he killed a guy in 1971—but he brought a lot of joy to Uncertain. “He is and was a living legend here,” Uncertain resident Zach Warren told the Marshall News Messenger after Lewis’s death in May. “People would come out for tours with Henry, and they didn’t care if they even caught anything, they just wanted to go with Henry. He was a character.”

Lewis attended the documentary’s debut in New York City. On the trip, Lewis “seemed just as impressed by the number of yellow cabs he saw” as with anything else the city had to offer, Ferguson wrote. The film was generally well-received, and it was awarded the Tribeca Film Festival’s Albert Maysles Documentary Director Award. Lewis’s sudden fame seemed to help him come to grips with his troubled past. “I’m thankful he had realized that in order to get to heaven with mom, he needed to ask for forgiveness,” Lewis’s daughter, Katheren “Niese” Lewis Nwakanma, told the Messenger. “I think his biggest thing was just forgiving himself and the documentary gave him the platform to do that. I know he had found God as his personal savior and that is my joy and my peace and comfort.”

Fittingly, Lewis died the way he lived: on Caddo Lake. Lewis spent the day before his death out on the water, catching fish and talking with old friends. “Nobody fishes like he fished,” Billy Carter, who operates Johnson’s Ranch at the Marina, told the Messenger. “He’s the end of a generation of fishermen here. He was family here to us in Uncertain. He said he wanted to be on Caddo Lake when he died and he was about 100 yards away. I know he’s been waiting to see his departed wife because everything changed for him when she died. He had a great last day here. He wished to die fishing and see his wife—if we could all be so lucky.”

Edgar Black Jr.

November 3, 1925—June 2, 2017

Few humans ever truly master anything. But Edgar Black Jr. tamed violent fire and smoke to create brisket that melted melt in your mouth. Black was one of the true Texas pitmasters. For 85 years, he helmed Black’s Barbecue, a joint that almost singlehandedly elevated Lockhart from a small-town afterthought to a true culinary destination. As Eater wrote in 2014, “Central Texas is the pinnacle of all the smoked meat meccas. And Lockhart is the capital.” Quite literally: the Texas House officially made Lockhart the barbecue capital of Texas in 1999, followed by the Senate in 2003. That’s in large part thanks to Black.

Black’s Barbecue was originally a meat market and grocery, and started during the Depression when Edgar Black Sr., then just a poor farmer and cattle rancher, “made a handshake deal with a friend who wanted to open a meat market,” according to Eater. The leftover meat became its own side business of barbecued brisket. Black Jr. took over in 1962 and made the side business into the main course. He died in June, at the age of 91.

Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim

May 8, 1928—July 21, 2017

You may know the East Texas plant by its giant statue of the guy with the buckled hat. That creation is the public face of Pilgrim’s Pride, but behind the scenes, Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim used his poultry prowess to perfect chicken. His company, one of the largest chicken producers in the country, gained a reputation for high quality products, winning countless and accolades from everyone from the Chili Appreciation Society International to Texas Public Relations Association. Pilgrim’s award-winning chicken chili recipe was later entered in The Congressional Record, but his hard-labored boneless whole chicken innovation—which won recognition from the public relations association—never quite caught on with consumers, and was eventually discontinued.

Pilgrim was born and raised in Pine, not far from the northeast Texas town of Pittsburg, where Pilgrim’s Pride is based and where it remains one of the area’s main employers. Outside that plant sits The Hat: a 37-foot-tall painted bust of Pilgrim, fitted in a suit jacket, a white shirt, a tie, and a ridiculously large pilgrim’s hat. A less conspicuous monument to Bo sits immediately below, where a life-size statue portrays him as a young man, sitting on a bench and reading the Bible alongside his favorite childhood chicken, Henrietta.

Pilgrim’s chicken empire started as a modest feet store in Pittsburg. “All we had in the beginning were a two-wheel buggy, a shovel, some burlap sacks, and Bo’s big ideas,” a longtime associate said in Pilgrim’s 2005 memoir, One Pilgrim’s Progress: How to Build a World-Class Company and Who to Credit. At one point, Pilgrim felt inspired to eat healthy, and so the company developed the first “lean chicken,” containing less fat and cholesterol that competing chickens and none of their artificial coloring. Nutritionally enhanced eggs soon followed. Pilgrim truly embraced the mascot role in the 1980s, when the company first began to take advertising seriously. “I put on a business suit and then donned a black buckled Pilgrim hat on my white hair,” Pilgrim wrote in his memoir. “With a name like Pilgrim, what could be more logical.” His trademark tagline? “Nobody likes a fat chicken.”

There were bad times though. According to the New York Times, in 1989, Pilgrim handed out $10,000 checks to eight Texas state senators two days before a scheduled vote on a bill that would weaken workers’ compensation laws, spurring a change in ethics laws. And as the chicken industry boomed and became crowded, Pilgrim’s hemorrhaged money in the 1980s and nearly sold out to Tyson’s before getting back on track. After Pilgrim grew following its purchase of ConAgra’s poultry division, it suffered a massive recall due to an outbreak of listeriosis, an avian flu epidemic, environmental violations, animal cruelty allegations, and raids targeting immigrant workers. His net value reached $1 billion at one point before his retirement in 2010. But even after his death in July at the age of 89, a piece of Pilgrim remained in Pittsburg, staring off into the distance from beneath his big, buckled hat.

Bill Bailey

February 2, 1939—July 27, 2017

The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo is a true celebration of the senses. There are incredible things to see, like wild, bucking broncos on one of the biggest stages in the sports. There are heart-stopping concoctions to taste, like deep-fried Oreos or deep-fried cookie dough or Snickers, which, well, those are deep-fried too, actually. You can pet the soft fur of barnyard animals (and you can never really escape the putrid odor of their poo). But as for the sound of the rodeo, that will always be most closely associated with Bill Bailey.

For 54 years, Bailey scripted the rodeo, his booming voice belting out the sport’s uniquely lyrical vernacular: mutton bustin’, barrel racin’, calf scramblin’—Bailey loved saying the words, and he loved even more being a part of the show. “He had a voice that could cut through steel,” Bob Tallman, who shared announcing duties for 35 years with Bailey, told KTRK. “It was him, and you knew it was him. When he spoke, people listened.”

The calf scramble was perhaps when Bailey shined most. He’d often use his microphone to encourage the young scramblers to move a bit faster, and he’d use his trademark “Bailey bump”—a playful little hip check—to try to coax the calves into the chalk square. Each year’s event would start with Bailey, before the Texas-style grand entry at the world’s largest rodeo, uttering the same classic phrase. “Emmett!” he’d shout over to the gate man, Emmett Evans Jr., “Open the gate and let me have ’em one more time!”

Born Milton Odom Stanley in Galena Park, Bailey filled out an application to work as a radio DJ in the 1960s, for a position that had been promoted using the song “Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home!” He agreed to make that his DJ nickname, and it stuck. After a long DJ career, Bailey turned to public service, winning the race for Harris County Precinct 8 Constable, a role he served in from 1982 to 2011. The career spawned Bailey’s second nickname in the rodeo world: “The Constable.”

The longer he announced, the more Bailey became intertwined with the Houston Rodeo. “Everywhere you look, there is a piece of Bill Bailey,” Carolyn Faulk, lifetime vice president of the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, told Bowlegged H Magazine in 2016, after Bailey retired. “He doesn’t just join—he participates. He gives with his heart, and he has a big heart.”

Bailey retired in late 2015, and had suffered from health problems ever since. In July, at the age of 78, Bailey passed away. One might say Bill Bailey finally went on home. His voice is still booming somewhere, that’s for sure: Open the gate, and let me have ’em, one more time.

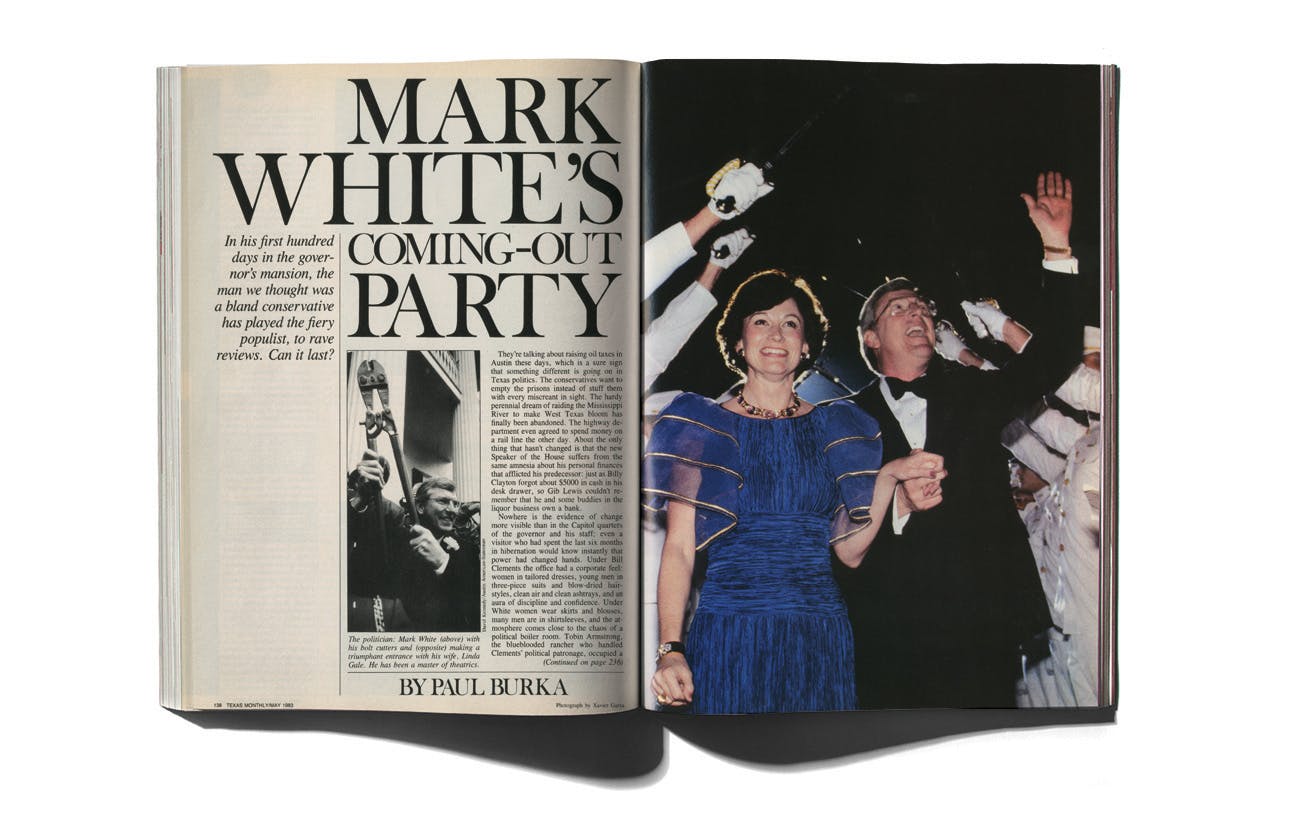

Mark White

March 17, 1940—August 5, 2017

Elected in 1982, Mark White served one term as the forty-third governor of Texas, but lost his re-election bid in 1987. During his tenure, the Democratic governor accomplished a lot, particularly in education. White’s “no pass, no play” for high school athletes changed scholastic sports in the state, and he implemented Texas’s first statewide testing standards.

According to the Houston Chronicle, White’s political career was guided by Sam Houston’s advice: “Do right and risk the consequences.” White certainly risked the consequences with his “no pass, no play” reform, which was a particularly explosive policy proposal in football-mad Texas. It may have doomed his re-election bid, but it certainly had a massive impact. In 1985, the Chicago Tribune reported that the law handed out six-week suspensions to 15 percent of varsity football players and 40 percent of junior varsity and other high school players, because their grades didn’t pass muster. Many games, junior varsity and freshman competitions in particular, had to be cancelled altogether. Even the band couldn’t play on: 35 percent of all high school band members in Texas were prohibited from participating in halftime performances due to the policy. The state’s influential high school coaches’s association considered actively opposing White’s re-election.

Still, White was undeterred. These were simply the consequences of doing right. “The other day a mother told me that her son couldn’t play on the local high school football team because he had failed his English courses,” White said during a television campaign ad in 1985. “I asked her if she agreed with me that her son needed to pass before he could play. She kind of looked down and then she looked me straight in the eye. ‘His father and I didn’t send him to school to play,’ [she said]. ‘We sent him to learn. Even if he makes the team, he won’t be a professional ballplayer. But if he doesn’t pass his classes, he’ll never be a professional anything.’”

White ran for Governor again in 1990, losing in the primary to Ann Richards. He’d never run for public office again, though he would go on to serve as chairman of the Houston Independent School District Foundation. In 2014, Houston ISD named a school after him. His political legacy may yet live on through his son, Andrew White, who announced his campaign for governor in December.

Dick Clark

December 15, 1944 to August 8, 2017

“Architecture is not just about a building. It’s about people. No matter how beautiful or functional the design, architecture’s true meaning is found in those who live their lives in the spaces we create.” That was the guiding precept of Austin-based architect Dick Clark, who, over the course of a near-fifty-year career, helped to create hundreds of such spaces—residential, commercial, dining—in which hundreds of Texans then spent their days. His impact was evident not only in his lifetime—the Capital City long ago dubbed him the “godfather of contemporary architecture”—but also at a celebration held in October, two months after he succumbed to a hard-fought battle with leukemia. At the remembrance, more than 1,000 admirers gathered at Austin’s Paramount Theatre to commemorate his legacy, watch a mini-documentary about his life, and sing along to tribute tunes with his old friend, Willie Nelson, who made a surprise appearance.

Dick Clark was the creative mind behind hundreds of stunningly modern stucco and limestone houses with steel accents, beautiful restaurants, and commercial spaces, both in Texas and around the world. After growing up in Dallas, he studied architecture at the University of Texas and went on to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design before returning to Dallas in 1969 to start his career with modernist Bud Oglesby at his firm, Oglesby Group Architects. Then, he took a job teaching at the University of Tennessee, where he was assigned to lead the Nicaraguan Architecture Students Program in Managua. This ignited his great love of travel and adventure, which led to teaching in Denmark, hiking in the Andes Mountains, cycling around China, and visiting more than eighty countries in his lifetime.

He opened his eponymous firm, Dick Clark Architecture, in Austin in 1979. Clark helped define the modern Austin vernacular and became a leader in the design community, training the next generation of Austin architects in his lively and prolific downtown office, winning more than seventy awards along the way. He became a specialist in restaurant design, earning a national AIA Award for 612 West and incorporating thoughtful design details based on his keen observations about how people dine in a space (he got so specific as to put hooks under bars for women’s purses). Other restaurants he designed include Mezzaluna, Bitter End, The Grove, Maudie’s Milagro, Cafe Annie’s, Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse Austin, Capitol Brasserie, Chuy’s San Antonio, and Kenichi Dallas. But beyond always designing with a deeply rooted sense of place, Clark was a charismatic, larger-than-life figure around Austin, one who was often surrounded by friends and fun wherever he went. A creator until the end, Clark designed a sculptural fountain while in the hospital a few days before his death. We hope Dick Clark is on one of his regular Hill Country drives in the sky in his vintage Porsche 356. —Lauren Smith Ford

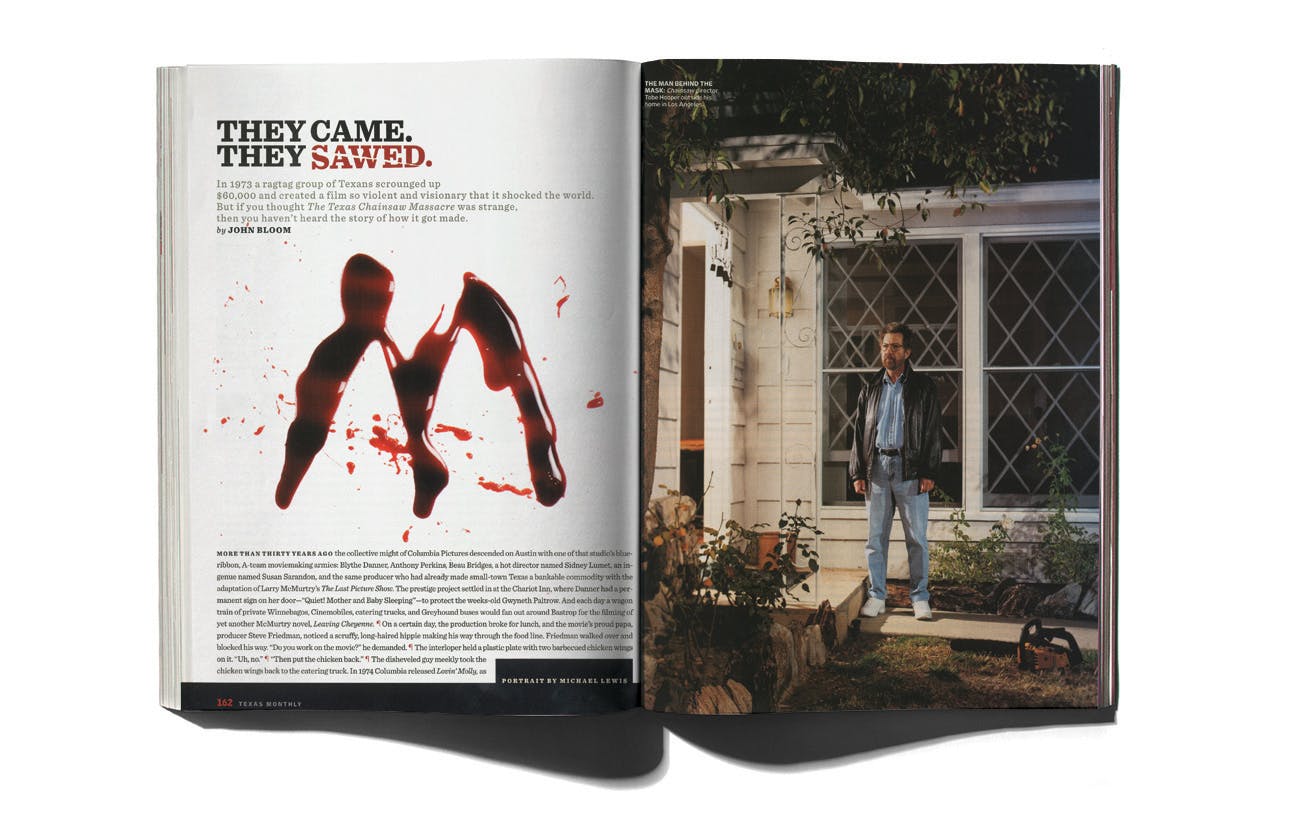

Tobe Hooper

January 25, 1943—August 26, 2017

Tobe Hooper just wanted to make art. Old-school visual masterpieces like those crafted by his favorite Italian directors, Frederico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. But in the early 1970s he was nothing more than a “long-haired hippy” hanging around the set of a movie based off of a Larry McMurtry book. But he was also hungry, and he wanted some chicken. “On a certain day, the production broke for lunch, and the movie’s proud papa, producer Steve Friedman, noticed a scruffy, long-haired hippie making his way through the food line,” Texas Monthly‘s John Bloom wrote in 2004. Friedman caught Hooper red-handed with a plastic plate holding two barbecued chicken wings and demanded he put the food back. Hooper obliged. That movie turned into nothing special, but Hooper, the disheveled chicken-stealer, would go on to make one of the most important films of the horror genre, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Hooper, who died in August at the age of 74, drew his inspiration for the film from, of all things, a rack of chain saws he saw while at a department store during the Christmas shopping rush in December 1972. “There were these big Christmas crowds, I was frustrated, and I found myself near a display rack of chain saws,” he told Bloom. “I just kind of zoned in on it. I did a rack focus to the saws, and I thought, ‘I know a way I could get through this crowd really quickly.’ I went home, sat down, all the channels just tuned in, the zeitgeist blew through, and the whole damn story came to me in what seemed like about thirty seconds. The hitchhiker, the older brother at the gas station, the girl escaping twice, the dinner sequence, people out in the country out of gas.”

His masterpiece cost less than $300,000. He used $60,000 raised by an Austin politician, and filmed in and around an old Victorian house in Round Rock with a crew that used just two vehicles—a Chevy van for the film equipment and a broken-down 1964 Dodge Travco motor home that doubled as dressing rooms. It was mostly panned by critics upon its release in 1974. A reviewer for Harper’s Magazine called it “a vile little piece of sick crap,” while an official from the British Board of Film Classification accused the movie of trafficking in “the pornography of terror.”

But its fantastically gory aesthetic would influence horror directors for generations to come. “Chainsaw was the first real ‘slasher’ film, and it changed many things—the ratings code of the Motion Picture Association of America, the national debate on violence, the Texas Film Commission, the horror genre—but it remained a curiously isolated phenomenon,” bloom wrote. “The film itself, involving five young people on a twisted drive through the country, is a strange, shifting experience—early audiences were horrified; later audiences laughed; newcomers to the movie were inevitably stricken with a vaguely uneasy feeling, as though the movie might have actually been made by a maniac.”

Hooper may not have been a a maniac, but he was certainly mad about moviemaking. Legend has it that his mother went into labor while sitting in Austin’s Paramount Theater. He was born hours later at a nearby hospital, in 1943. When Hooper was young, his father would often sneak out of work and take Tobe and his mother to the movies. “I saw a movie every day,” he told Bloom. “I think I learned cinematic language before I learned language. I think I was a camera.” His first camera was his father’s Bell & Howell 8-millimeter, and he employed his family and classmates as actors in miniature films. “They were little stories. ‘Here’s my cousin and her boyfriend. She’s tied on the railroad track. Here comes the tricycle train with a beer-can smokestack,’” he said. “I did a vignette version of the Frankenstein story using kids from the school. Later I heard kids talking about my movie in the lunch line, and that’s what made me know this is what I wanted to do.” He only lasted two years at the University of Texas after enrolling in the university’s then-new film school in 1962 before going off to pursue his dream. He shot a few short films and promo videos before realizing that the only way to reach the audience he hoped to have would be through the horror genre.

After Chainsaw, Hooper would direct a few more horror classics, including the scary-as-hell “Salem’s Lot,” a made-for-TV miniseries that aired on CBS in 1979 and was based on a vampire novel by Stephen King, and “Poltergeist” in 1982, a critically acclaimed ghost story written and produced by Steven Spielberg (who was ultimately credited for the film’s three Academy Award nominations). Hooper’s career saw many successes, but his legacy is undoubtedly Leatherface.

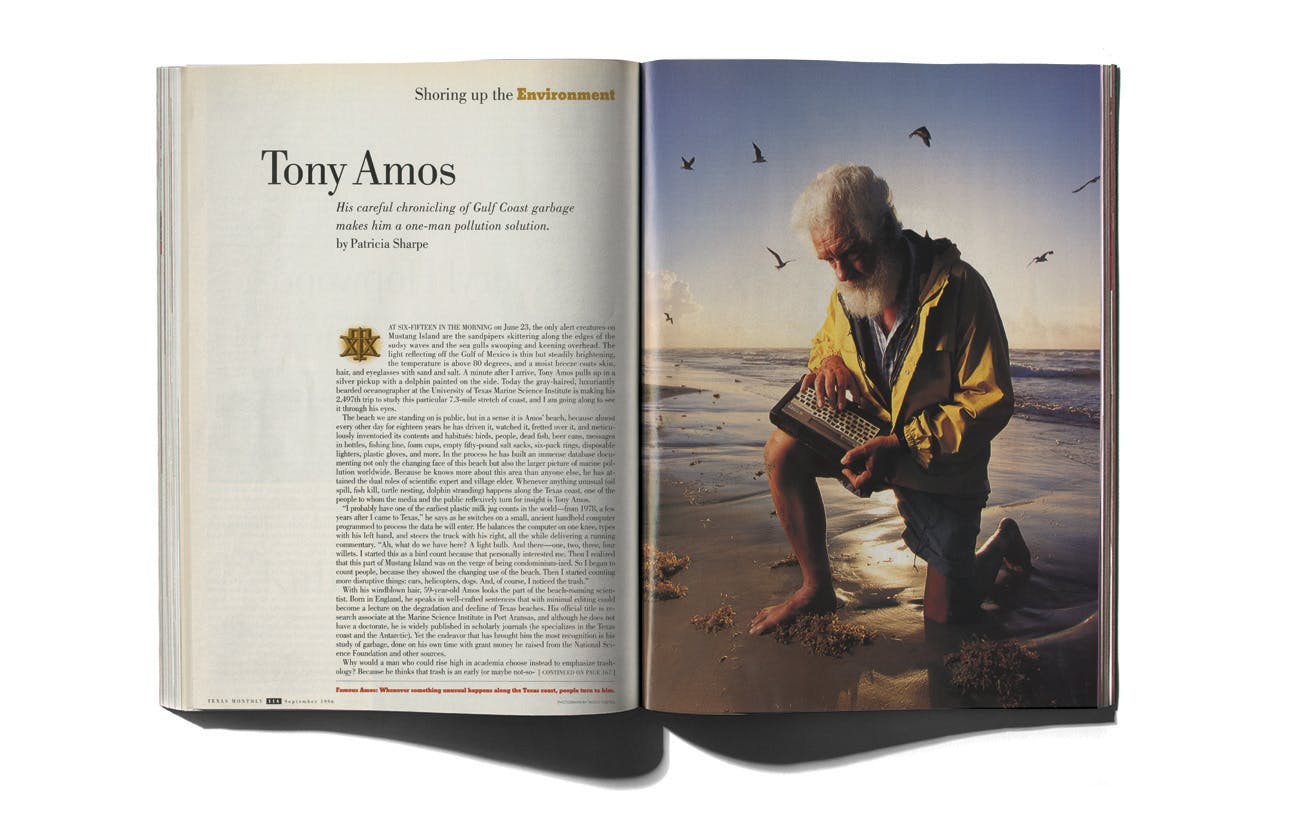

Tony Amos

September 2, 1937—September 4, 2017

Before he died in September, following a long battle with cancer, Tony Amos, 80, had one request: that his ashes be scattered at the place he loved most—the sea. “What will my legacy be…” Amos, the founder and former director of the Animal Rehabilitation Keep (ARK) in Port Aransas, pondered during a recent interview with Mission Aransas—a national estuarine research reserve—shortly before his death. “To have influenced people to pay some attention to that beautiful place, a place that’s gorgeous, especially early in the morning when the sun comes up, and when you see, still, the abundance of nature.”

Amos, a native of England, made it his lifelong mission to maintain that abundance of nature that he learned to love and appreciate. Amos started going on research missions in 1963, braving the frigid weather and rough seas of polar region waters. In his decades-long career, Amos traveled to the Antarctic 35 times, and he has touched every ocean.

He began working as a research fellow at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute in 1976, despite never receiving a college degree. He went on to conduct more than 6,000 beach surveys and author more than 1,500 articles about protecting beaches and wildlife. Colleagues described him as “larger than life,” a legendary figure in the sea life rehabilitation community along the Coastal Bend, and a unique character whose long, flowing white beard made him unmistakable.

“When I first came to Texas, I did not know much about my new home, so I wanted to find out more about the birds, which has always been a passion of mine since I was quite young,” Amos once said. “In order to do that I chose a section of the beach on Mustang Island, a seven-mile section, and decided to go on a regular basis to look at the birds. I started finding animals that were in distress or dead, and that really started what we now call the ARK.”

With ARK, Amos helped save distressed sea turtles and birds, including piping plovers, red knots, brown pelicans and bald eagles. More than 2,500 sea turtles alone have been rehabilitated and released since ARK began in 1982. In 1983, Amos was named the Port Aransas Region Coordinator of the Texas Marine Mammal Stranding Network. During his tenure, he saved 1,090 marine mammals, spanning twenty species of cetaceans, including fin whales and spinner dolphins.

For a few days every week, Amos would walk the same seven-mile stretch of beach on Mustang Island, counting. Birds, dogs, people, trash, turtles, helicopters, jellyfish, cars. Anything, really, was worth recording, even the messages beachgoers left written in the sand. “When my son was a kid and he would ask me, ‘Daddy, what are you doing?’” Amos recently remembered, “I’d say, ‘I’m measuring the ocean.’” Amos would observe the weather, using a half-dozen stock phrases to note the obvious—rain, showers, fog, overcast, partly cloudy, clear. But there were rare occasions for which Amos was forced to create an entirely different kind of classification. “There are times—and by the way, you people who go to the beach, you should try this from time to time, you probably don’t realize you’re experiencing this—but there are times here, when the weather is so perfect, that you’re not aware of it being all around you,” Amos told Mission Aransas. “You are in almost a cocoon of really enjoyable environment. You may be fishing, you may be looking for shells, but you don’t realize that your body is not sweating, you’re not tired, you’re enveloped by it. So I simply write, ‘beautiful thing!’ with an exclamation mark. Then there are times, slightly less than that, maybe a front has just gone through but your body is not quite up to that coldness, but otherwise it’s got all the rest of the attributes. That’s called ‘Nice!’” Amos took all the “Beautifuls!” and all the “Nices!” and plotted them on a graph.

Days before Amos passed away, ARK suffered severe damage from Hurricane Harvey. Staffers were able to evacuate the animal population, but the facility was nearly destroyed. Luckily, Amos never saw it that way—he died days after the storm hit, at a hospital in San Antonio, on his way home after a trip to view the solar eclipse. There will likely be a long recovery process, but Amos’s colleagues at ARK are undeterred—one of them promised in an interview with KUT that the center will be rebuilt “bigger and better.” Not long after Amos’s death, the facility was renamed in his honor, as the Amos Rehabilitation Keep (you can donate to the ARK through the Anthony F. Amos Endowment).

On a Saturday evening in September, along that stretch of Mustang Island Gulf Beach that had been named in his honor, Amos’s friends and loved ones, along with a five-year-old green sea turtle named Picasso, who had been rehabilitated at ARK after it became entangled in fishing nets, gathered to say goodbye to Amos for the last time and honor his legacy.

“Tony Amos was massively gentle, endlessly amused by the absurdity of life,” his son, Michael, said on the beach. “He was charming, professionally objective, talented, and genuinely fascinated by the subjects he chose to speak on.” Then Michael sprinkled his father’s ashes on the back of Picasso, gently set the turtle down on the soft sand, and released him into the sea. The crowd parted for Picasso to pass through the tide, cheering and crying as he slowly flippered his way off of the shore and toward the orange sun, which lay low over the water. The abundance of nature was all around them.

“Come on little turtle, off you go,” Amos’s wife, Lynn, said. “The sun’s about to set.”

Apolonio Reyes

February 8, 1920—September 25, 2017

The Greatest Generation lost one of its finest when El Paso’s Apolonio Reyes died in September at the age of 96. Reyes was a member of Rifle Company E, 141st U.S. Army Infantry, 36th Division, a National Guard unit activated in 1940 that was comprised mostly of Hispanic men from three high schools in El Paso. Reyes’s company went on to play a large role in the liberation of Rome during World War II, and is considered one of the bravest companies to have fought in the war. With Reyes’s death, only three of the company’s 250 men remain alive.

During one harrowing mission in January 1944, in Monte Cassino, the company crossed a river in southern Italy, a move that would count as one of the war’s greatest military mistakes. “When the group got up to the mountain, the Germans were waiting for them,” Arnulfo Hernandez, who interviewed Reyes for a book, The Men of Company E: Toughest Chicano Soldiers of World War II, recently told the El Paso Times. “They were at an advantage on the hill and decimated the 141st Regiment. Many were captured.” Still, the company went on to fight some of the most harrowing battles of World War II, braving the difficult mountain terrain from Salerno, San Pietro, Velletri, and Anzio. They freed Naples and Rome, captured Nazi number-two Herman Goering, and moved through southern France and across the Rhine River into Germany, where they helped end the war.

Reyes was discharged in 1945 and was awarded five Bronze stars and a combat infantry badge. Despite their heroism, members of Company E had gone largely unrecognized for years following the war. In 2015, Reyes was among the few surviving members of Company E who were honored during a ceremony at a bronze memorial in El Paso, built in 2008, paying tribute to the company. “I’m very proud of what we did and everyone who came out of Company E. Everyone spoke very nicely about us,” Reyes told the Times in 2015. “Sitting next to these guys is special. I remember very little about the things we went through, but I will always remember my brothers from Company E.”

Y.A. Tittle

October 24, 1926—October 8, 2017

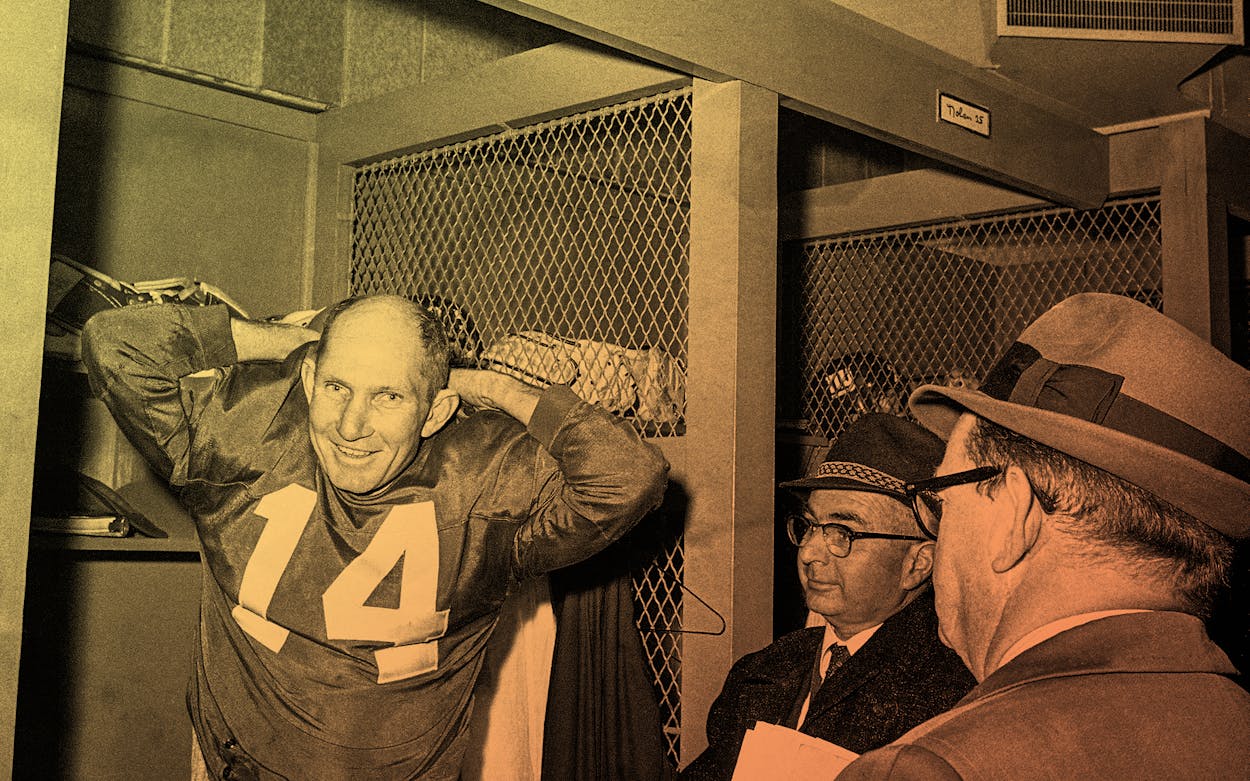

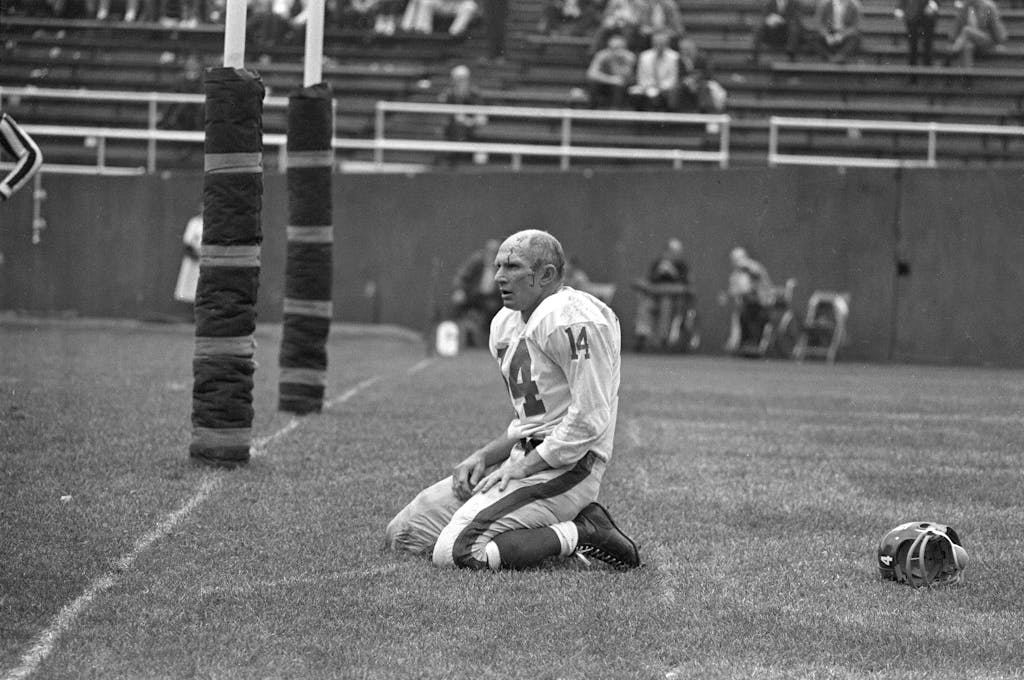

For all of the excellent quarterbacks in our football history, Yelberton Abraham Tittle, Jr. will be remembered as one of Texas’s most important signal-callers. He helped usher in football’s modern era of pass-first offenses, along the way opening doors for high-octane gun-slingers on high school fields, college stadiums, and NFL palaces. The wise, tough as nails leader seemed larger than life, and fitting for such a mythical figure, he was ultimately immortalized—like the bronze statue of a gladiator—by a single black-and-white photograph.

It was 1964, the final season for Tittle, then 37 years old but going on 60—a prematurely receding hairline had earned him the nickname “The Bald Eagle”—and the veteran quarterback was kneeling in the grass, his helmet-less head hanging down, and his body worn, battered and bloodied—a hero in tragic decline. The prior play, he’d attempted to throw a screen pass, which was intercepted and returned for a touchdown. Tittle had been drilled by a 270-pound defensive end for the Pittsburgh Steelers and taken a helmet straight to the sternum. The blow knocked the breath out of him.

By this point, Tittle was already a legend. He’d won the league’s MVP award the year before, made seven Pro Bowls, and had led the Giants to three straight championship game appearances, though they’d lost each one. In seventeen seasons, he threw for 242 touchdowns and 33,070 yards, smashing records along the way, including the record for single-season touchdown passes, 36, which Tittle set in 1963 and stood for the next 21 years.

Tittle’s records were eventually toppled, but his grit has arguably met no equal. In his long career he’d suffered a partially collapsed lung, a broken left hand, a crushed cheekbone, broken fingers, fractured vertebrae, separated shoulders, and badly torn muscles. “Every injury I ever had in my lifetime, I could tape it,” he told Smithsonian Magazine in 2007. “Every injury I ever had, I could Novocain it.”

But the pain that was captured in that 1964 photo was like nothing he’d felt before. He spent that night in the hospital, where he was diagnosed with a cracked sternum and a concussion. He played the next week, leading the Giants to a win over the Washington Redskins. By the end of the season, the Giants had limped to a 2-10-2 record, once again leaving Tittle short of a championship—the one accomplishment he never reached—so he decided to retire. The injuries he sustained in that photo, Tittle would later say, “made me one thing I never was. It made me gun-shy. For the first time in my life I didn’t want to get hit, because I couldn’t get up.”

Tittle apparently hated that photograph for much of his life, which was used for nearly every obit following his death in October, at the age of 90. “That was the end of my dance,” Tittle said ten years ago, when looking at the photo. “A whole lifetime was over.” And yet, at the same time, a whole lifetime was forever preserved.

Echo McGuire Griffith

January 29, 1937—October 29, 2017

The curse of being Buddy Holly’s high school girlfriend is that, inevitably, you will always be known first as Buddy Holly’s high school girlfriend. But BHHSGF had a name, and it was a great name, a lyrical name: Echo McGuire Griffith. And being BHHSGF was hardly something Griffith felt cursed by. In fact, she fully embraced it, reveled in it, and accepted the responsibilities that came with it.

They were born four months apart—Buddy was older—and were delivered by the same doctor. Griffith said she first met Buddy in the fourth grade at Roscoe Wilson Elementary School, and they became friends toward the end of ninth grade. They dated through their time at Lubbock High, and, years later, Griffith fondly recalled their courtship. As a couple, they went to classmate Nona Gregg’s eighteenth birthday party at the K.N. Clapp Party House in Lubbock, and attended the Y-Teen Sweetheart Banquet together on Valentine’s Day. Holly was apparently a talented leatherworker, and he crafted a pair of chaps for her, with Griffith’s initials on one leg and his own initials on the other. He did the same with a hand-tooled pair of boots. “He was a gentleman,” Griffith later told KCBD. “He also had a serious nature about him, and as far as his career, he was very dedicated.”

The couple graduated in 1955. Though Holly and Griffith went their separate ways—Griffith off to college, Holly staying in Lubbock to chase his dream of being a rock star—they still remained a couple through her first two years in college, even when she transferred from nearby Abilene Christian University to York College in Nebraska. “Being so far away from Lubbock put a strain on my relationship with Buddy,” Griffith later said in an interview with a publication from Eastern New Mexico University, according to the York News-Times. “During the fall semester, he drove up to visit me in York, which helped to break up the long term away from home. Then, of course, we were together while I was in Lubbock for the Christmas vacation.”

By that time, Holly’s fame had already taken off. He’d recorded several records, appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, and had gone on tour. When Griffith returned home for Christmas break in her junior year, she saw that the directions their lives would eventually split them. She was a devout Christian and was uninterested in the inevitably sinful life of a rock musician’s girlfriend (one time, when Holly opened for Elvis in Lubbock, he took her backstage to meet the pelvis-lunging legend; Elvis asked her if he could kiss her, and Griffith turned him down. “I wasn’t that kind of girl,” she later said). Griffith broke up with Holly. She even burned his love letters, something she would later come to regret.

A few years after the break-up, Holly died in a plane crash. Echo was devastated when she heard the news. By that time, she’d already moved on and gotten married, but she’d always remain Buddy Holly’s high school girlfriend. Griffith and her husband, Ron, later formed a singing duo that performed Buddy Holly’s music. Echo would wear a retro poodle skirt, and a gold necklace that Holly’s brother gave her after his death that Holly had wanted give her before they split up. In between songs, she’d tell stories of their time together, Echo and Buddy, the lovers of Lubbock High.

In 2001, Echo gave Texas Monthly’s Joe Nick Patoski a tour of a new showcase dedicated to her at the Buddy Holly Center. Patowski wrote:

Echo McGuire Griffith shows me the new Echo McGuire showcase, paying tribute to Buddy’s high school sweetheart, the girl before María Elena. Her frilly prom dress, the necklace Buddy gave her, and the stuffed hound dog he and his first performing partner, Bob Montgomery, signed are all on display. She introduces me to her husband, Ron, who has a habit of telling people that he is the man who stole Buddy’s girlfriend. She tells me with a sweet smile that they broke up because of what Buddy was doing, playing rock and roll. “I have felt like I’ve had the call of God all my life,” she says. “We were headed in different directions.”

Since Holly died young, everyone that ever knew him became the keepers of his flame. It was a responsibility that Griffith, perhaps, held dearer than most. With her death in October, at the age of 80, that flame became a little less bright.

In memory of Echo McGuire Griffith, here’s her favorite song from her high school boyfriend:

Frank Liberto

February 20, 1933—November 5, 2017

Frank Liberto’s was a God in the concession snack scene, a creator of worlds so vast that one could get lost in his cheese sauce forever (that wouldn’t be a bad thing).

Frank Liberto was the Father of Nachos.

Liberto had snacks in his blood. He was a third-generation San Antonio businessman, the grandson of an entrepreneur who ran peanuts through his coffee roaster and peddled it to parade watchers and circus spectators. Liberto had the gene, and he expanded the family concession business, Ricos, in the 1970s, after he had a finger-food epiphany inspired by a side dish common in San Antonio’s Tex-Mex joints.

“The traditional order of nachos is something that’s served over a plate of grated cheese and jalapeños,” Tony Liberto, Frank’s son and the current CEO of Ricos, told Texas Public Radio after he died in November—one day before National Nacho Day—at the age of 84. “You put it in an oven. It takes, I would imagine, ten minutes or so to prepare one dish. So he thought, it was just cheese sauce, ‘I could just warm the cheese up in a warmer, throw some chips in a bowl and ladle some cheese over it and throw some jalapeños on it.’”

It was a stroke of genius, one matched only by another necessary innovation credited to Liberto: a thicker chip, one that wouldn’t immediately degrade into a moist mess and wilt beneath the blanket of melted cheese. He’d done it: perfected the ultimate snack. The stadium nacho was born.

“He introduced it to Texas Ranger stadium in 1976 and it became a hit right off the bat,” Tony said. The creation sent concession sales flying, its cheesy ripple of good luck touching nearly every snack item that sat next to it for sale—popcorn, hot dogs: they would never be the same again. All sales skyrocketed. In 1976, the Rangers sold $800,000 worth of Ricos’s nachos alone.

Though Liberto didn’t invent the nacho (that title probably belongs to Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya of Piedras Negras, Mexico), he modified the dish to the version that most living nacho eaters came to know and love. Liberto lays sole claim to the “Ballpark Nacho” (a redundant classification if there ever was one), and for that, we are all eternally grateful.

Liz Smith

February 2, 1923—November 12, 2017

New York lost one its most famous Texan voices when Liz Smith, “the grande dame of dish,” died at age 94 at her Park Avenue apartment in November. The Cowtown native and bottle blonde moved to New York toting two suitcases a few months after graduating with a journalism degree from the University of Texas. Over the years she rose to become one of the most influential gossip columnists of the modern era, writing for Cosmopolitan, the New York Daily News, and the New York Post. At her career’s apex, her columns were syndicated in sixty papers nationwide. Smith became something of a celebrity in her own right, and counted many prominent Texans as her close friends, including former Governor Ann Richards and journalists Molly Ivins, Dan Rather, and Bob Schieffer. In a 2005 interview with Smith in Texas Monthly, Evan Smith called her “the queen bee of the ex-Texans.”

Smith spent her career cozying up to celebrities, always weighing how reporting a particularly salacious detail would affect her future ability to write about that person. In a profile published in the New York Times this July, she told the paper, “I needed access to people. And you’re not supposed to seek access. You’re just supposed to be pure and you go to the person you’re writing about and you write the truth. Nobody can do it totally.” But, she added, “everybody gives up something to be able to do a job, a demanding job. . . I gave up being considered ethical and acceptable, for a while.”

Over the years she cultivated a particularly close relationship with Trump, arguably helping create his role as a media personality. In 2015, she penned a column titled “I Think I Invented the Trumps.” She was a frequent guest at Mar-a-Lago in the 1980s, visits that she later realized put her in a tricky situation. “I was left holding the bag, ethically, because I had foolishly appeared to have accepted a lot of favors from him,” she told the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin in September 2016. “The truth was I thought I could get him to give me money for my charities. He never gave me a dime. And I got the criticism I deserved.” The biggest scoop of her career was breaking the news of Donald and Ivana’s bitter split in 1990. As the Washington Post wrote after Smith’s death, “The Ivana-and-Donald story made Smith a star, establishing her as the highest-paid print journalist in the country. And it lifted Trump to a new level of fame and infamy. He relished the idea that he was the talk of the town, both in the boardrooms from which he’d always felt excluded and in the barrooms where, he believed, middle-class New Yorkers aspired to be like him.”

Smith appeared in the pages of Texas Monthly many times over the years. In 1997, she reminisced in the magazine on her time at the University of Texas. “I adored UT so much. If I had my druthers, I would still be there, on campus. But a girl has to eat,” she wrote. In 2009, shortly after the New York Post killed Smith’s column, Pamela Colloff asked her “What is gossip, exactly?” Her response was illuminating: “Gossip is unsubstantiated rumor, really. But let’s not knock it. It’s the most egalitarian thing. I mean, anybody can do it. It’s very democratic. It doesn’t cost you anything. Everybody does it. Families especially—they’re the worst.” —Sonia Smith

Ruth McClendon

October 5, 1943—December 19, 2017

Ruth McClendon was a people’s politician, in the sense that she wasn’t really a politician at all. That’s not to say she never held political office—she served as a Democratic representative in the Texas House from 1996 to 2016—but as she walked the halls of the Capitol and, perhaps more important to McClendon, the neighborhoods of her San Antonio district, she never really succumbed to the shady traps that befall so many in the political class. Instead, she stuck to her convictions. Even when her bills were doomed to certain failure, she’d still back them with all of her might. And her constituents were better off for it.

“In an age where there is so much tribalism, Ruth was a lady, and she treated everybody with respect,” McClendon’s longtime friend and colleague, former state senator Leticia Van de Putte, told the San Antonio Express-News after McClendon died of cancer in December, at the age of 78. “She could disagree with someone’s opinion and still uphold their dignity as a person. That’s a rarity in today’s political climate.”

Her strength of character was never more clear than during her final session in 2015. After undergoing surgery to remove water from her brain, she was so weakened that she required an electric scooter to get around and had trouble speaking. She still managed to pass a landmark bill that created a commission to study exonerations, an issue she’d been passionate about for years. It passed the House by a 134-6 vote, and even though it was weakened in the Senate, her legislation still went on to establish an innocence panel in Texas. During the same session, she also passed legislation that allowed drug users in seven densely-populated counties to swap used needles for sterile ones.

One of the most poignant images from that session was of McClendon at the speaker’s dais, issuing House congratulatory and memorial resolutions. So severely weakened that she could hardly read aloud or hold the gavel, she did the job anyway, finishing the task with a surprisingly loud “crack” of the gavel. As Texas Monthly wrote when we named her to that year’s “Best Legislators” list, “the look of joy on her face was inspirational.”