When Cathy McBroom stepped into the judge’s chambers in the summer of 2002, she thought her heart was going to stop. She had been told the judge was a big man, but she’d had no idea just how big until he started rising from behind his desk. He was six feet four and at least 260 pounds—“literally larger than life,” she’d later tell her best friend, shaking her head in wonder. Dressed casually in khakis, a button-down white shirt, and a sports coat, he took off his glasses, gave her a broad grin, and in a booming baritone said, “Cathy, I’m Judge Kent. Welcome to Galveston. Have a seat.”

Cathy, a 44-year-old mother of three, tried to keep her breath steady as she glanced around the room. It looked like a movie set, with lofty ceilings and the U.S. and Texas flags hanging behind the judge’s desk. Shelves of law books lined one wall, and on a credenza was a photo of the judge standing with President George H. W. Bush and his wife, Barbara. Spread across the floor was a giant rug emblazoned with the image of an eagle, the federal seal. Through six-foot-high windows, Cathy could see ships making their way across the Gulf of Mexico.

“Now, Cathy, are you sure you’re ready to take on this job?” the judge asked, sinking back into his leather chair and throwing his legs over the top of his desk, resting one huge shoe on top of the other. A few days earlier, she had received word that he was looking for a new case manager to oversee his docket and schedule his day in the courtroom. Cathy’s résumé had impressed him. Since graduating from Channelview High School, near Houston, in 1976, she had worked mostly for law firms, first as a receptionist and then as a legal secretary. In 1999 she had been picked from more than one hundred applicants to be a judicial assistant at Houston’s federal courthouse. When she had heard about the open position in Galveston, she told her husband, a shift worker at a chemical plant, that this was her moment—a chance to make more than $70,000 a year and start a nest egg for the family.

The judge cocked his head as he appraised her. Blue-eyed and brunette, Cathy was attractive, a trim woman who ran marathons with a Houston-area running club. But that afternoon, she was hardly flaunting her looks. She was dressed in a navy skirt that fell just below the knees, a matching navy jacket that buttoned up the front, and low-heeled pumps. Despite the summer heat, she was also wearing stockings to give herself a more businesslike appearance. She tried not to blush as she said, “Sir, I know I would do a good job for you.”

The judge nodded, and after a few more minutes of conversation, he stood up to shake her hand. “Cathy, I think you’re really going to enjoy working here,” he said.

He was right. As the first weeks turned to months, Cathy thrived in her new job. She arrived at the courthouse each day as soon as it opened, often skipping lunch to stay on top of all the hearings. In the courtroom, she sat at a desk just below the judge’s vast bench, where she assisted in selecting jury panels, assembled the judge’s written directives, and passed his orders to the attorneys. She couldn’t be happier, she told her friends and family. She loved watching him swagger into the courtroom, she said, the bottom of his great black robe flapping behind him like the tail of a kite. She loved the way jurors stared at him, awestruck, when he welcomed them to his courtroom and declared them “the real judges of the facts.” It was amazing, Cathy added, how even the $500-an-hour attorneys spoke to him reverentially.

Almost exactly one year after she’d taken the job, on a Friday afternoon in August 2003, Cathy was walking down the hall when she saw the judge, who had just stepped out of his private elevator. She snapped to attention. He was returning from a long lunch with friends, and as usual a courthouse security officer was accompanying him to his chambers. The judge saw Cathy and waved at her. “I hear there’s a new exercise room somewhere around here,” he said. “Want to show it to me?”

“It’s right here,” said Cathy, opening the door to a small room that had recently been equipped with a weight bench and some free weights. It was barely ten feet from the command center where the security officers worked, and she quickly led the way in. Suddenly, before she could utter a cry, the judge grabbed her, holding her head with one hand and lifting her up to crush her mouth against his. With his other hand he yanked up her blouse and bra, then tried to force his way into her skirt, tearing at her panty hose.

Somehow, Cathy broke away and backed across the room, so panicked she could barely speak. “Judge, what are you doing?” she finally gasped. But he kept coming, grabbing at her again, forcing his tongue down her throat, his breath smelling like cigars and alcohol.

“Tell me you want me,” he murmured. “Tell me you want me.”

“Judge, please! The officers are right outside! They’re going to hear you.”

For a moment, the judge looked at her, a grin spreading on his face. “Do you think I give a f— what they hear?” he asked. “Do you really think I care?”

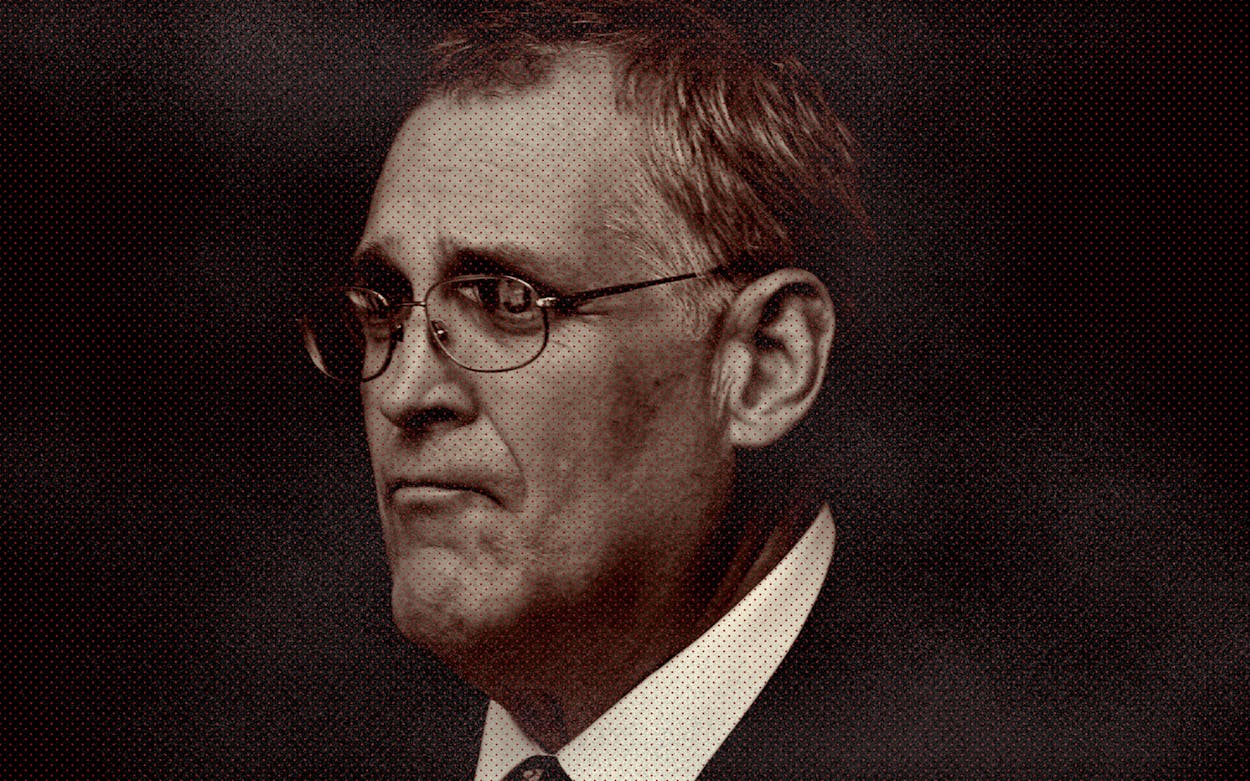

Until earlier this year, when he became known as the “sex judge”—the first federal justice ever to be indicted for sex crimes—59-year-old Samuel Barstow Kent was the most powerful person in Galveston, a figure of such magisterial authority that citizens called him King Kent. He was the federal district judge for Galveston and its surrounding counties, not only handling all the civil lawsuits filed with the U.S. district clerk at the city’s downtown federal building but also presiding over every criminal trial prosecuted by the U.S. attorney’s office. Just up the interstate in Houston, federal legal proceedings were shared among eleven district judges. But for the Galveston area, there was only Judge Kent, “a jurist of seemingly impenetrable force,” as one newspaper reporter wrote.

Raised in Houston, where he had played center on Memorial High School’s 1966 state champion basketball team, Kent had made the dean’s list at the University of Texas at Austin, graduated from UT’s law school, and then moved to Galveston with his wife and two young daughters to work for Royston Rayzor Vickery & Williams. He soon became one of the firm’s most outstanding attorneys, representing international owners of ocean liners and doing defense work for insurance companies and manufacturers. He was renowned for his photographic memory of case law, and his closing arguments at trials were so perfectly prepared that other lawyers would sit in the courtroom just to hear him speak.

In the late eighties, when the sitting federal judge, Hugh Gibson, was preparing to retire, Kent began angling for the prized lifetime appointment. He sent notes to Senator Phil Gramm, who would be choosing Gibson’s successor. He took local civic leaders, whom he thought Gramm might be calling as references, out to lunch, and he drove the senator around Galveston whenever he visited, standing beside him in receiving lines and whispering the names of everyone he met. No one was surprised when Gramm picked him. His nomination flew through Congress, and in October 1990, at the mere age of 41, Kent took over the sixth floor of Galveston’s federal building.

From the start, Kent made it clear to those with cases in his court that they were not going to take advantage of his youth. He set strict trial deadlines, refusing to let lawyers prolong proceedings with protracted depositions or other pretrial maneuvers—tricks he knew all too well. He fined them if they arrived late to court or showed up unprepared, even going so far as to levy a $100 fine against a brash assistant U.S. attorney who didn’t stand and show him the proper respect when he spoke.

He did not suffer fools in his courtroom. When someone made a poorly formed argument, Kent raised his eyebrows and snorted impulsively, and he regularly interrupted if he found the examination of a witness boring or repetitive. His written opinions, often circulated among astonished lawyers, could be shockingly caustic: In one, he ridiculed two lawyers for their “amateurish pleadings,” and in another he described a motion as “patently insipid, ludicrous and utterly and unequivocally without any merit whatsoever.” In 1993 he gained even more fame in legal circles when he reined in some of the country’s most prominent and flamboyant lawyers, including Houston’s Joe Jamail and New York’s David Bois, in a highly publicized antitrust lawsuit in which American Airlines was accused of predatory pricing. Among Kent’s startling rules: No party in the case could file any pleading more than fifteen pages long, and no lawyer was allowed to make side remarks to the jury or gallery, including “gestures, facial expressions, movement of the body or hands, or the manipulation of any papers or objects.”

If his imperious manner was jarring, few could deny he got results. In his first five months on the job, Kent closed more than two hundred civil and criminal cases, and lawyers were soon swapping stories about his “rocket docket.” He was, without question, a brilliant judge, easily handling everything from high-stakes maritime disputes and multimillion-dollar class-action claims against chemical companies to elderly citizens’ lawsuits over Social Security payments. Because he plowed through so many cases, sometimes with two or three rulings a week, Kent also became a celebrity of sorts among the 540,000 residents of his four-county district—an activist judge who did not hesitate to wade into local battles. He presided over a lawsuit in which a group of citizens demanded that Santa Fe High School ban overtly Christian prayer from its graduation ceremony, and he also took on the case of a Galveston tavern owner who had been sued by Starbucks for selling a homemade beer he called Star Bock. He brokered a settlement between the Island’s richest family, the Moodys, and the Island’s biggest hotel developer, Tilman Fertitta; ordered a full-scale cleanup of a notorious hazardous waste site; and forced all shrimpers on the Texas coast to use the kind of nets that would give endangered sea turtles the best chance of escaping. In one memorable decision, he required a resident to not only restore wetlands that he had filled illegally but also erect a billboard informing passersby that he was fixing the damage.

When he wanted, Kent could radiate immense charm. During breaks in trials, he would sit on a couch in his chambers, smoking a cigar and regaling visitors with stories. An amateur Civil War historian who loved reading Shelby Foote, he would describe major battles from beginning to end. He would recite poetry and Scripture. Some days, Kent would bring along his pet bulldog, the General, who’d wander around the office, sniffing people’s legs. And periodically, he would go to lunch with some of his lawyer friends, drink a couple glasses of wine, and tell jokes, gesturing with his massive arms and laughing so loudly that people in the restaurant would turn to see the commotion.

At some of those lunches, his jokes would turn ribald, or he’d spy a comely waitress and say, “Get a look at the rack on her.” And there were times, like at parties thrown by law firms, when he would get rip-roaringly drunk and try to hug the women around him. Some lawyers had heard a disconcerting story in which Kent, after a drink too many, had pushed a young female clerk against a wall at a party and groped her within minutes of meeting her. Others had heard about a paralegal begging her boss, a well-known Houston attorney, not to ever send her to drop off papers for the judge again at the Galveston courthouse, because he had attacked her in his chambers. But it was hard to imagine that a man like Kent, whose self-possessed, outsized personality everyone seemed to love, would do such things. What’s more, none of the lawyers dared openly question the judge’s behavior. They knew Kent would be hearing their cases until he retired; the last thing any of them wanted was to get on his bad side.

Nor did Kent’s employees dare complain about him. The federal building was rife with stories about the judge’s getting rid of those he believed were disloyal to him. According to one rumor, a U.S. marshal working for Kent in Galveston suddenly found himself transferred to a lowly job in the jail division of the Houston federal courthouse after he’d complained about having to drive the judge to the airport. According to another rumor, a probation officer was transferred to a job in Houston with less pay after he’d seen Kent come to work one morning at ten-thirty and said jokingly, “Hey, Judge, keeping banker’s hours?” Although Kent’s attorney insists the two stories are completely untrue, the fact was that staff members were convinced that Kent could easily ruin their careers. “If you didn’t kiss his butt,” said a former courthouse employee, “then just like that, you could be out of a job.”

Cathy staggered out of the exercise room, desperately tugging at her bra and straightening her blouse, tears streaming down her face. The security officer who had been with the judge was nowhere to be found. Another officer nearby seemed preoccupied with reading material. Cathy raced to the fourth floor and found her supervisor in the district clerk’s office. “He attacked me!” Cathy blurted out. The supervisor knew exactly whom she meant. She closed her office door and said that the judge had once done something similar to her, forcing a French kiss.

“I’ll be honest,” the supervisor said. “You can file a complaint, but remember that he’s a federal judge and you’re just an employee. You serve at the pleasure of the court. He’ll beat you.”

At the end of the day, Cathy drove home and told her husband. Livid, he asked her if she’d done anything to lead Kent on. “Of course not,” she replied, taken aback. Her husband saw only one option: for her to quit her job and go back to a law firm. “You’re not going to work for that man,” he said.

But when Cathy returned to the courthouse on Monday, unsure of what to do, Kent sent word that he wanted to see her in his office. “Hey, I don’t know how you felt about what happened on Friday,” he said, “but I hope it didn’t upset you too much.” He gave his usual big grin. “You’re a beautiful woman, and at that moment, I couldn’t help myself. I’m sorry,” he said, with a congenial pat to her shoulder. “Let’s just forget about it. I don’t want you to give it a second thought.”

She tried not to think about it. She told herself the judge had simply gotten carried away. Cathy knew he could be a flirt: He had once told her she had nice legs, and on another occasion he had given her a hug that was just a little too tight. She had also learned that he had started drinking heavily in the mid-nineties, when his wife was afflicted with brain cancer. After she died, in 2000, he had quickly remarried, but his drinking hadn’t slowed. “Maybe he was just drunk,” Cathy told her best friend, Charlene, a schoolteacher in San Antonio, when they talked that week. “Maybe it was a one-time thing.”

And for the next few months, Kent was the perfect gentleman, complimenting Cathy on her work in front of attorneys and juries. Relieved, Cathy began to relax. Then, late in 2003, Kent casually asked her to his office to discuss a work matter. No sooner had she walked in than he lunged at her, trying to kiss her while pawing at her breasts. “Come on,” he said, winking at her as she twisted out of his arms. “You only live once.” (The details of Kent’s assaults come from interviews, court hearings, and statements made to a congressional committee.)

It became a predictable cycle: After several months of model behavior, the judge would suddenly make a move. Pin her against a wall. Grope her through her clothes. Tell her that he wanted to give her oral sex and have her return the favor. The following day he’d apologize, promising with a shrug that it would not happen again.

A few courthouse employees began to notice Cathy in her office on some days, shaking and disheveled, perspiration staining her clothes. She had told a couple women whom she trusted what Kent was doing, and they offered their offices as refuge when she wanted to hide. Cathy figured she knew what would happen if she tried to slap him: He would have her fired, which meant she would have to go back to a law firm, working nights and weekends for half the pay. That is, if she could find a job at a law firm. A vengeful Kent could very well blackball her with other lawyers—certainly those who practiced in his court—and Cathy would have to start over in some other profession, not exactly a promising prospect for a middle-aged woman.

And anyway, she loved her job. She was proud to have become a case manager without having earned a college degree. She received health and retirement benefits that she would never get in the private sector. Why should she give up her career because of something the judge was doing? Instead, she resolved to manage her interactions with Kent. She tried not to display much of a personality in his presence and was careful to never be alone with him. Tired of her husband’s questions, she stopped giving him details about Kent’s attacks, saying simply that she was keeping the judge “under control.”

One day in 2005, Kent summoned Cathy for a mandatory meeting. She was relieved to see his secretary, Donna Wilkerson, at her desk, right outside his chambers. Kent had never attacked her while Donna was nearby. As Cathy walked in, Kent asked her to shut the door. Before she could sit down, he was out from behind his desk, wrapping her in a hug so savage she thought her lungs would collapse. As he began to kiss her, Cathy heard the door open. There was Donna, who gasped and quickly walked back out.

The next day, desperate to explain, Cathy asked Donna to lunch at a little restaurant on the seawall. Blond and petite, 41-year-old Donna had grown up on a small farm twenty miles from Galveston and married her high school sweetheart. In 2001, after working at legal firms for nineteen years, she had been hired by Kent to replace his longtime secretary, who was retiring. The word around the courthouse was that Kent watched after her. He had boosted Donna’s salary from $55,000 to $70,000, and he was lenient with her hours, as he was with most of his staff, allowing her to leave the office if he was away. Donna, in turn, was protective of the judge, fiercely regulating who could or could not see him. She and her husband had occasionally gone out to dinner with Kent and his second wife, and the judge had attended a few of their kids’ high school sporting events. Cathy knew she was taking a gamble talking to her. But she simply couldn’t stomach the idea that Donna might think she was having a fling with the judge.

“He’s been attacking me, Donna,” Cathy said. “He stops for a long time, and I think it’s over, and then he starts it all up again.”

There was a long silence. Donna’s eyes filled with tears. “What is it?” Cathy asked.

“He’s done things to me too,” Donna finally said, and she put her face into her hands and sobbed.

Donna was too overcome with emotion to say anything else. Over the years, she had told only two close friends about the judge’s assaults, and even then, she had revealed few details. She had not said, for instance, that he had gone after her the very first week she had started work, leaning down and kissing her on the lips after returning from a retirement luncheon for her predecessor. She had not mentioned how, in the following months, he had pressed his hands against her breasts when she walked past him. She had not talked about the way he slipped up behind her while she was at her desk, running his hands down the inside of her shirt. When she saw him approaching, she would push herself as close to the desk as possible, her arms and legs squeezed together to discourage him. But some days, he was relentless. Once, he’d trapped her in her chair, pulled down her pants, and briefly buried his head in her crotch before she threatened to scream at the top of her lungs.

At lunch, Donna and Cathy agreed to warn each other if one of them saw the judge come barreling into the courthouse from an alcohol-fueled lunch so the other would have time to disappear. They knew better than to take him on directly: Kent, who by then had been on the bench for fifteen years, was more powerful than ever. He had even started referring to himself by his King Kent nickname. (“He always chuckled when he said it,” recalled a lawyer friend, “but you never could tell if he was really kidding.”) One day a young man had seen the judge, whom he did not recognize, smoking his cigar on the first floor and said, “Sir, there’s no smoking in a government building.” “Son,” Kent had snapped, “I’m the federal judge here, and I’ll smoke anywhere I by God want to.” On another occasion, Kent had ordered the investigation of a man who he said had cut him off in traffic and made a gunlike gesture when the judge had blown his horn. “I want that son of a bitch arrested for making a terrorist threat against me,” Kent had bellowed. Lawyers had taken to calling him by a new nickname: Judge Samu, a play on Shamu, the killer whale who performed at SeaWorld.

The best way to deal with Kent, both women knew, was to avoid him. And throughout much of 2006, Cathy did. Kent never bothered her, and she found herself hopeful. “If I can stay under the radar, I think he’ll leave me alone,” she told Charlene.

But in March 2007 Cathy misplaced an exhibit used in a trial—a rare mistake on her part that had resulted in an administrative reprimand. Kent summoned her to find out what had happened. Cathy sat down in a chair in front of his desk, apologized, and waited for his reaction. After a few moments of silence, Kent told her everything would be fine. Cathy stood up to leave, and he said, “All right, now, give me a hug. Come on. I’ve been good to you.”

“Just a little one,” Cathy said. She knew immediately that she had made a mistake. The judge grabbed her backside with one hand, pulling up her sweater and bra with the other. He got his mouth on one of her breasts, then grabbed her head with both hands and pushed it into his crotch. Cathy tried desperately to twist away as Kent’s bulldog leaped from a corner of the room and began barking.

Suddenly, the judge heard footsteps in the outer reception area. “You know,” he whispered as he let her go, “I keep you around because you are a great case manager. That doesn’t change the fact that I want to spend about six hours licking your c—.”

Cathy raced to the fourth floor and hid in an office in case he came looking for her. When she got home late that night, she walked into the bathroom and stared at herself in the mirror. Then she grabbed a vase on the vanity and threw it at her reflection, shattering the mirror.

“He’s beaten me,” she told Charlene the next day. “I’m never going back.”

Cathy submitted a request to her supervisor for a transfer, claiming that Kent had assaulted her, and two weeks later, she was at the federal courthouse in Houston, working for some staff attorneys who mainly handled prisoner litigation. Most days, she found herself staring blankly at the wall. She had trouble reading case files she had been given. She stopped running, lost weight, and developed so much back pain that she couldn’t sit in a chair. She often felt her heart racing and thought she wasn’t going to be able to breathe. She was prescribed muscle relaxants, Ambien, and Xanax. Nothing seemed to help.

At home, she had difficulty cooking or doing any chores. “What’s wrong with you?” her husband kept asking. “You should be happy. Your life is back to normal.”

“I need help,” she said. “I’m struggling.”

“Cathy, you’re out of Galveston,” he exploded. “You’ve still got your job with the same pay and benefits. You won!”

But that was not how she felt. Especially not on the day she heard from a woman she had worked with in Galveston. “Judge Kent is saying you were sexually obsessed with him,” the woman said, “and that the only reason you requested a transfer was because he wouldn’t dismiss the administrative reprimand you got for that misplaced court exhibit. Cathy, he’s got people down here calling you Cathy McWhore. Even the ones who know he’s lying are afraid to say anything. They’re scared that if they tell the truth, he’ll get rid of them.”

“What about Donna?” Cathy asked, her heart sinking.

“She’s on his side too.”

About a month after her transfer, Cathy learned that she had the right to file something called a complaint of judicial misconduct with the U.S. Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans, which oversees federal judges in Texas. In the stairwell of the Houston courthouse, the only place she could think of where she wouldn’t be overheard, Cathy pulled out her cell phone and called an attorney she had known since childhood.

“Cathy,” he said, “the system set up to investigate complaints against federal judges is designed with one goal in mind: to protect the judges. At best, the Fifth Circuit will give him a slap on the wrist.” He paused. “And Cathy, if you file that complaint, Kent and his attorneys will do everything to destroy you and your family. If I were your attorney, I’d advise you not to do it, especially if you have anything to hide about your personal life. You will have nothing to gain and everything to lose.”

The fact was, Cathy did have a past. Her marriage had not exactly been happy—it had started going south years before she went to work for Kent—and a couple times she had strayed with other men. Still in the stairwell, she called Charlene. “I have the chance to do something about this judge, and it’s going to destroy me in the process,” she said.

“So what do you want to do?” Charlene asked.

There was a long silence. “I want to make sure he doesn’t do to someone else what he did to me,” Cathy finally said.

A few weeks later, she mailed her complaint to New Orleans and separated from her husband, informing him that she needed to wage her fight alone (she did not tell him about the extramarital affairs). She moved into a small town house nearby so she could be close to their thirteen-year-old son, the last of her three children to live at home. Days later, Kent’s office received the complaint. Cathy had not only written about the various times the judge had attacked her but had also mentioned Donna Wilkerson and the fact that she’d once admitted to being abused too. Reading the document, Donna was beside herself. How dare Cathy expose her? Although Fifth Circuit rules kept these investigations private, she knew her secret could easily get leaked to the newspapers.

And what if her husband found out? She had never told him about Kent’s assaults. A tough, sturdy man who worked as a natural gas measurement technician, he was the kind of guy who at the mere suggestion of Kent’s attentions would have driven to the courthouse to punch the judge himself. She couldn’t risk such an overreaction—her husband would get thrown in jail and she would most certainly lose her job. Donna began to panic. Her husband might blame her for allowing any of it to have happened. Or accuse her of having an affair and throw her out of the house.

So when Kent gathered his sixth-floor employees and addressed Cathy’s complaint by saying, with immense self-confidence, “Please, we’re going to be just fine,” Donna found herself sighing with relief. The judge later took her aside and said, giving her a firm look, “I’m going to tell the Fifth Circuit that I tried to kiss you a couple of times but that you told me to stop and I did.” Donna nodded. All she had to do was repeat the same story, and everything would go away.

That June, a special Fifth Circuit investigatory committee of judges and attorneys arrived in Galveston to interview those in Kent’s circle. Because they were not put under oath, many of the courthouse employees were not forthcoming. “Our first priority was job preservation,” a security officer would later say. “We were worried Kent would get a transcript of our testimony and come after us if he did not like what he had read.”

At least a couple of Kent’s more loyal employees criticized Cathy. One mentioned that she had seen Cathy flirt inappropriately with men at a bar during happy hour. When it was Donna’s turn to testify, she coyly said she didn’t know anything about the relationship between the judge and Cathy. She then repeated the story Kent had given her about trying to kiss her a time or two. It was nothing serious, she told the committee: “I dealt with it, I took care of it, and it stopped.”

Cathy, preparing for her own testimony, looked for a lawyer to represent her. Everyone she approached turned her down; one lawyer said his practice would be irreparably harmed if he went against Judge Kent and lost. On a whim, she called the famously theatrical Rusty Hardin, one of Houston’s best criminal defense attorneys. Hardin was so outraged by Cathy’s story that he agreed to represent her pro bono. But he cautioned her not to expect too much from the Fifth Circuit judges, regardless of what she testified.

Predictably, in September, the court released an order of reprimand, not even three pages long, announcing that Kent had been placed on a four-month leave of absence, during which he would continue to receive his $165,000 salary. The reprimand acknowledged that “a complaint” had been made about Kent sexually harassing an employee of the federal judicial system, but it didn’t say whether the judges had found the charge credible. Nor was there mention of Cathy’s allegation of outright assault. “A complete whitewash,” snapped Hardin. He ordered his investigator, a former Houston homicide cop named Jim Yarbrough, to reinterview everyone the Fifth Circuit committee had talked to and to find witnesses it had ignored.

The investigation was hardly easy. A court security officer refused to answer the door when Yarbrough visited his home. A woman who had clerked for Kent said her law firm didn’t want her talking, and another said she would do so only under court order. A third, who had apparently developed an eating disorder while working for Kent, also refused to say anything. Still, Yarbrough managed to uncover enough new details—a former clerk told a story about Kent going after her so aggressively at a Houston cigar bar that a marshal had to physically pull him away; a young briefing attorney talked about Kent forcibly kissing her in his chambers—that Hardin decided to file a criminal complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice, demanding that Kent be charged under a rarely used federal statute of sexual assault (the statute covers only assaults that occur on federal property).

“If you agree to this,” he told Cathy, “everyone is going to know who you are. It’s not going to be easy for you or your family. Are you ready for that?”

“I think so,” Cathy replied.

What neither Hardin nor Cathy knew was that the FBI was already on the case. Two FBI agents arrived to question Cathy at Hardin’s office. Still, their background was primarily in white-collar corruption, and they were clearly skeptical about building a case. They asked Cathy if she had flirted with Kent or dressed in tantalizing ways. Did she have any personal vendetta against the judge? They quizzed her about her sexual indiscretions while married and demanded to see her financial statements, telephone records, and e-mail accounts.

After the interview, they still didn’t seem sure of what they had. Arresting a federal judge for sexual assault? On the testimony of one woman? At best, it looked to be another Anita Hill—Clarence Thomas fiasco.

“You would think I was the criminal,” a distraught Cathy told Hardin.

“It’s just beginning,” Hardin replied.

In fact, as soon as Kent learned that there were FBI agents sniffing around, he hired another famous criminal defense attorney from Houston, Dick DeGuerin, who quickly went in for the kill, telling news outlets that Cathy’s relationship with Kent had been “enthusiastically consensual.” If things had really been so bad, he pointed out, how did Cathy go years without making a complaint? She was clearly nothing more than a disgruntled employee with “a false accusation that cannot be corroborated.”

There was, at least, one piece of good news—or so Cathy thought. In an administrative meeting in late October, federal judges for the Southern District of Texas voted to remove Kent from Galveston. The judges had seemingly heard too many stories about Kent’s abuse of power; allegations had sprung up that he was inappropriately favoring certain lawyers in his decisions and in settlement negotiations. Kent, they decided, needed to be somewhere he could be supervised once his Fifth Circuit suspension was over.

And where was that? In a courtroom on the eighth floor of the Houston federal courthouse—one floor above Cathy McBroom.

On January 2, 2008, Kent and his staffers from Galveston, including Donna, arrived for work at their new Houston courtroom. Nearly thirty of Cathy’s supporters, including her son, were waiting by the front doors of the courthouse, holding signs that read “Impeach Judge Kent!” Later, a federal judge who knew Cathy said to her, disgustedly, “What are you hoping to accomplish with such a public demonstration?”

Although she never laid eyes on Kent, Cathy began having nightmares, dreaming he was slipping downstairs from his courtroom and attacking her, stuffing a cigar down her throat. She saw Donna once, on a street corner downtown, but Donna pretended not to see her. Other courthouse employees kept their eyes glued to the floor when they walked past her. “I’m a pariah,” Cathy told Charlene. “I can’t win.”

After reviewing the FBI’s evidence, prosecutors from the U.S. Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section decided to let a grand jury rule on whether to indict Kent. Besides presenting Cathy’s claims about his purported abuse, they presented the jurors with allegations that Kent had accepted but failed to report gifts from lawyers and that he had sold his Galveston home for a tidy profit in a deal arranged by a lawyer who had dozens of cases in his court. It seemed more and more unlikely they’d get Kent on the sex charges: Donna, for instance, arrived in the grand jury’s room, sat in the witness chair, and promptly repeated the story she had told the Fifth Circuit.

But after months of deliberations and to almost everyone’s surprise, the jurors ignored the allegations of financial impropriety and in August 2008 indicted Kent on charges of abusive sexual conduct and attempted sexual abuse. It was unheard of: Never had a federal judge been charged with sex crimes. The story quickly exploded in the media, though throughout the coverage Kent remained remarkably sanguine. At his arraignment, in his usual booming voice, he announced that he was “absolutely, unequivocally not guilty” and declared that he would bring a “horde of witnesses” to fight such “flagrant, scurrilous” charges. Afterward, he took the private elevator to his office and returned to the courtroom to conduct routine business.

Legal insiders following the case also doubted the charges would stick. After all, a willing grand jury, as the old saw went, could indict a ham sandwich. DeGuerin, for his part, announced to reporters that he had sources who could vouch that Cathy was obviously enamored with the judge, and he went so far as to ask for a hearing so that he could introduce evidence of Cathy’s sexual past—even though he had to have known that a federal rape shield law prevented him from doing so. The prosecutors and FBI agents, growing worried, reinterviewed Cathy nearly a dozen times. “Was there ever a time when you sat on the judge’s lap?” they asked. “Did you ever say to him that your legs were your best assets because you’re a runner?”

Months passed, and Cathy and Hardin wondered if their case would be dropped. But in January 2009, Hardin got a phone call. The grand jury was handing down an amended indictment. Judge Kent, stated the new charge, had abused another court employee and lied about it to the Fifth Circuit. The indictment accused him of forcing this employee to repeatedly “engage in a sexual act”—including oral sex—and of using his hands to “penetrate or attempt to penetrate” her.

“My God,” gasped Cathy when she heard the news. “That has to be Donna.”

Just before Thanksgiving, the prosecutors, desperate to get more evidence against Kent, had started squeezing the lawyer who was involved in the sale of the judge’s home, pressing him for everything he knew. The lawyer happened to be one of the two close friends that Donna had confided in about Kent’s abuse. After getting him to confess what he knew, the FBI agents soon found Donna—at the mall, Christmas shopping with her kids—and served her a subpoena to appear before the grand jury once again.

A few days later Donna was in her garage when she saw Kent pull up in his car. He had heard, he said as he walked up, that her friend had been speaking to the FBI. “Donna,” he said in a serious tone, “he told them that we had been together”—Kent made quote marks with his fingers—“a few more times. But all you have to do is repeat our original story, and everything will be okay.”

He drew himself to his full height. Giving her his most confident look, he said, “Donna, we need to circle the wagons. Everything’s going to be fine. I don’t want you to worry.”

Donna could barely stand to look at him. “I’m so sick of all of this!” she screamed.

Trembling, she marched into the kitchen, where she saw her fourteen-year-old daughter doing homework at the table. For the first time, she wondered what her daughter would think if she learned that her mother had been sexually abused for so long and done nothing about it.

Donna decided to tell her husband. The conversation lasted through the night. They talked the next day, and then the next. As she had predicted, he was furious. How, he asked, had she allowed this to go on for so long without telling him? At one point he became so upset that he got in his car and drove off, leaving Donna in the driveway, screaming hysterically. She was terrified he would head to Kent’s house with his gun to shoot him. He returned the next morning, saying he would do his best to support her.

A few days later, Donna slipped away from the courthouse and, accompanied by a lawyer she had hired, drove to the FBI’s Houston office to confess the truth. When the revised indictment was publicly announced, DeGuerin stuck to his same tactics: Kent and his secretary, he told the press, had had a longtime consensual relationship, and Kent had failed to reveal the affair to the Fifth Circuit’s investigatory committee because he was a gentleman. Donna, he said, had turned on the judge only to save her marriage.

Kent, however, was a different man. One person who saw him in those days described him as “looking mortally wounded.” A law clerk at the courthouse called Donna at home. “Donna, he can’t believe you’ve turned against him. I really think he’s going to kill himself if you testify. He’s even asked me to check to see if his life insurance policy has a suicide exclusion clause.”

“If he does kill himself,” Donna replied, “it’s not my fault, and it’s not your fault. He’s done to himself what he’s done.” Shaking, she hung up the phone, stunned that for once she had not bowed to the judge.

A rumor began circulating that the FBI had found at least six other women who had agreed to testify against Kent. In the face of the mounting evidence, DeGuerin met with prosecutors and arranged what, by all accounts, was a splendid plea bargain: 33 months in prison on a simple obstruction of justice charge for Kent’s lying to the Fifth Circuit about the extent of his sexual contact with Donna. As part of the agreement, Kent would sign a rather toothless statement in which he acknowledged having “nonconsensual sexual contact” with Cathy on two occasions and “nonconsensual sexual contact” with Donna from 2004 through at least 2005. (Kent has neither confirmed nor denied the other incidents related in this story.) He would not be required to say a single word about his actions in open court—and because the assault charges would be dropped, he would never have to register as a sex offender.

Still, it was the most spectacular downfall the justice system had seen in decades. A federal judge, who in nineteen years on the bench had presided over more than 12,000 cases, had been caught himself in a flagrant abuse of power. In February 2009 the courtroom was packed as Kent stood before a visiting federal judge and, in a voice that barely rose above a whisper, pleaded guilty. “Gone was the thunderous voice, the swelling, megalomaniacal demeanor, the vehement proclamations of innocence,” wrote a Houston Chronicle reporter. Donna sat in the courtroom and watched, a row in front of Cathy. Stricken with guilt, she still had not spoken to her former co-worker. But after the hearing, she asked Cathy to meet her in an empty jury room.

“I know you hate me because I stuck with him,” she said. “All I can say was that my life was a living hell. I thought he would destroy me if I fought back.”

“Donna, I don’t care what it took. You did it,” Cathy said. “Who could have imagined that we would get this far?”

At his sentencing a few months later, Kent described himself as “completely broken,” and he apologized to his family and to his staff. Cathy and Donna, sitting in the courtroom, waited for him to also acknowledge them, but no apology came. The judge overseeing the case, however, had agreed to allow the women to make statements of their own. As Kent looked at the floor, Cathy stood at the lectern and, trying to keep her voice from cracking, called Kent a “drunken giant” who “used his incredible power to his own benefit and hurt so many people in the process.” Donna followed with her statement. “He abused those around him and misused the power that his position brought him,” she said. “How sad is it that he, himself, is the biggest bully of them all.”

As he walked out of the courthouse to his car, Kent gently held his wife’s hand. He did indeed seem broken. But he hadn’t given up the fight entirely. Before being sent to a federal facility in Massachusetts, he attempted to retire by claiming he was disabled due to serious health problems, which would have given him his full salary for life. When the Fifth Circuit denied his disability status, he then submitted a written letter of resignation to President Barack Obama, effective June 1, 2010, which would have allowed him to receive a full year’s salary while in prison. Members of the House Judiciary Committee Task Force on Impeachment were so outraged by his impudence that they fast-tracked impeachment proceedings against him. Cathy and Donna were flown to Washington, D.C., to testify, and their statements were broadcast on CNN and printed in newspapers around the country. Kent, finally realizing that there was no way to beat the two women he had nearly destroyed, agreed to write another resignation letter, effective June 30, 2009.

He has not been heard from since. No one is sure what he will do when he gets out, which could be as early as November 2010. The deposed king of Galveston will be broke and without a law license. According to DeGuerin, Kent’s wife is very ill, and with Kent’s resignation, she no longer has health insurance. “She is a victim too,” added a close friend. “She continued to stand by him even when she learned what he had been doing to his employees. How does she ever get over that?”

The judges on the Fifth Circuit have since decided to shut down the Galveston bench altogether and move its cases to other federal courts. Donna and Cathy, meanwhile, continue to work at the Houston federal courthouse. Donna, who is a secretary for an auxiliary judge, has managed to remain with her husband, despite what she says are “some difficult moments.” She regularly sees Cathy, who is a case manager for a Houston federal judge. Now divorced, Cathy continues to live in the same little town house she moved into after filing her complaint with the Fifth Circuit, sharing custody of her son. She’s training to run a marathon in February, and every now and then, she goes out on a date. “I’m very, very careful about who I agree to see,” she said recently with a laugh.

When Cathy and Donna have lunch, they don’t talk much about the old days. They discuss what they’ve learned about themselves that week in their separate therapy sessions, then swap the usual courthouse gossip. “For years, we were afraid of saying anything to anyone,” says Donna. “Now it’s nice to lean back and relax.”

They still notice when people in the courthouse hallways give them second glances. “It’s like they are not sure, despite all that’s come out, that we’ve really told the whole truth,” says Cathy, shaking her head. “After all this time, we’re still being judged.”

But the other day, a woman came up to Cathy and said, “I want to shake your hand.” For a moment, Cathy didn’t recognize her. Then she realized: It was the Houston paralegal who years ago had begged her boss not to send her back to the sixth floor of Galveston’s federal building. “Thank you for what you’ve done for all of us,” she said to Cathy. “Thank you.”