This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In 1946 a man named Ray Ramirez killed one of the last jaguars in Texas. The act seems ignominious now, but the cat was accused of killing 33 calves and had a $50 bounty on its head. Jaguars are hulking, two-hundred-pound beasts, the largest cats in the Americas. They are jungle dwellers, and back when the Rio Grande Valley looked like a jungle jaguars used to roam there. The last ones disappeared from the Valley in the early fifties, but two of the jaguar’s smaller relatives—the ocelot and the jaguarundi—still hang on in the remnants of cover, fugitives from wilder times.

I started going to the Valley a decade ago in the company of seasoned birdwatchers, but we always kept a lookout for cats. And for good reason: even birders acknowledge that cats are the ultimate statement on wildness. They also carry physiological engineering to perfection, and in the forest they take the role of apparition—never quite touchable, always beckoning. I have had glimpses of cats. In a cloud forest in Mexico I watched a wide-eyed, furry kitten, either an ocelot or a margay (the young of both look very much alike), perched in a bromeliad growing on the side of a tree. After a couple of minutes it skittered down the tree and leapt in front of me into the forest. In Costa Rica I saw a jaguarundi drink quietly from a stream and then slink into the jungle. But these are freeze frames from distant places. I was somehow missing exotica in my own back yard. So gradually the notion took hold that someday I’d try to see an ocelot, or even a jaguarundi, in Texas.

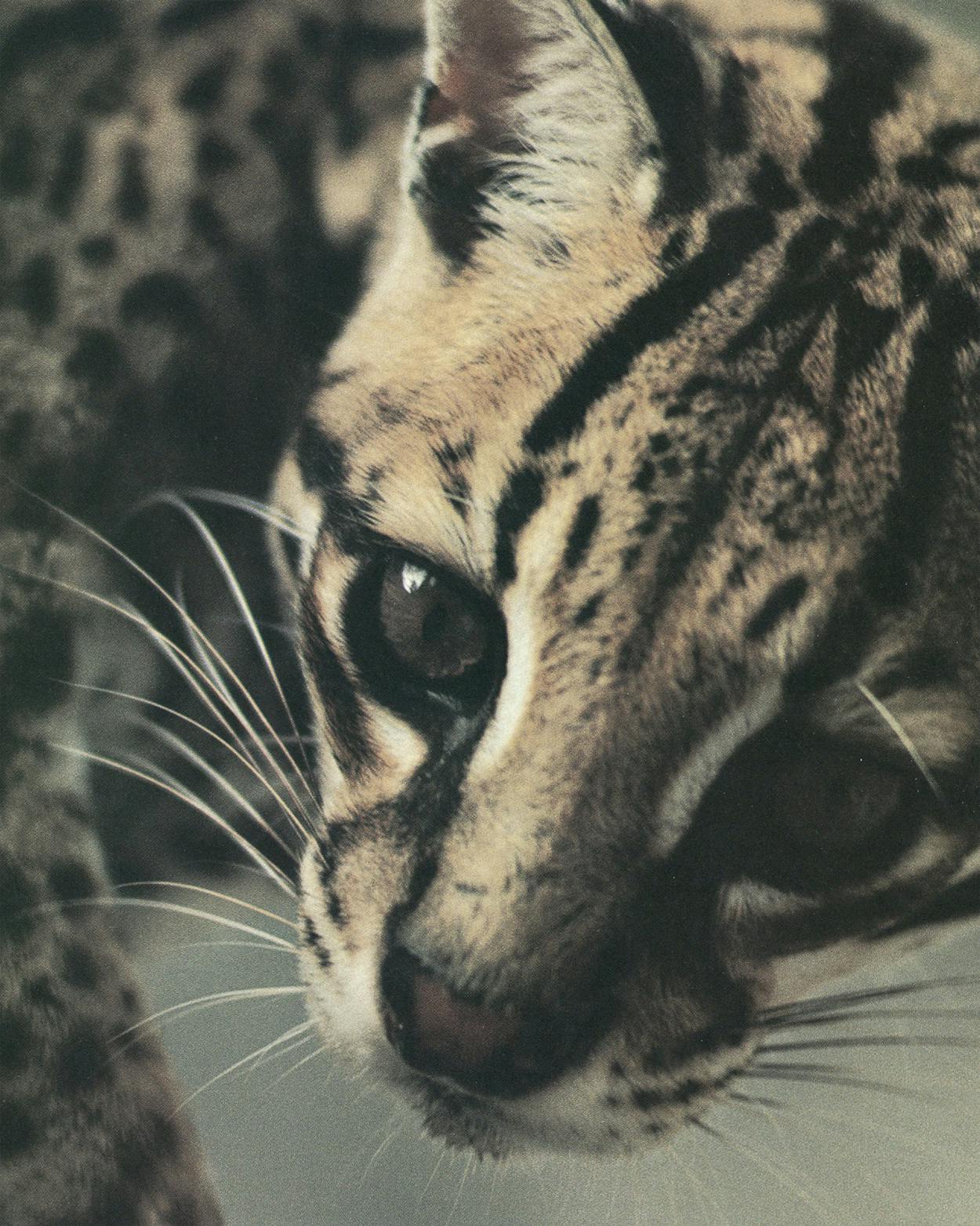

The ocelot is a small, lithe cat, in the twenty-pound range, with a champagne-colored coat liberally sprinkled with black rosettes. Most people have encountered it either as a fur coat or as a pet in a rhinestone collar; both of these manifestations are now illegal in the U.S. The jaguarundi is long, low, and dark—deep rust red or sooty gray—and so reclusive that hardly anyone ever sees it. Weighing about fifteen pounds, it might be mistaken for a slinky house cat. But on closer inspection a jaguarundi looks more like a weasel—the small head, the sloping Nefertiti skull, the wide eyes, the low center of gravity. It couldn’t exactly be described as beautiful, like an ocelot, but it looks shrewd. It commands respect. Both of these cats are rare (and getting more so), and they are secretive on two counts —they seek dense vegetation and they hunt almost always at night. They’re far too small to kill calves, but they have been known to cause a few hurricanes in the hen house.

In 1970 the number of ocelot pelts imported into the U.S. peaked at 140,000 (the number dropped after that, in anticipation of a ban that went into effect in 1972). In West Germany—still the biggest legal importer of spotted-cat furs—an ocelot coat, made from about eight pelts, goes for $40,000. The jaguarundi is not prized for its fur, but both it and the ocelot are caught in a land squeeze. From South Texas to Argentina, what threatens them most is loss of habitat. They are now the objects of concern of various governments and many zoos and international wildlife organizations. One can tentatively say that they aren’t on the road to extinction; they are, however, on the path to containment and maintenance, a situation that for a wild creature seems like a contradiction in terms.

Not only are these cats rare but they are zealously guarded by those assigned to study and protect them. Given this tenor of protectiveness, I needed entree into the world of endangered species. That’s why I wanted to meet Mike Tewes. He is a young mammalogist who has taken it upon himself to plumb the mysteries of the ocelot and the jaguarundi in Texas.

Of the 37 species of cats, only a handful have been studied thoroughly—the lion, tiger, leopard, cheetah, mountain lion, bobcat, lynx, and snow leopard. All the others are so reclusive or restricted to such inhospitable range that mammalogists have been reluctant to track them; it would be like studying the behavior of a needle in a haystack infested with poisonous snakes and biting insects. But Mike, despite the Valley’s heat, ticks, mosquitoes, rattlesnakes, and thorny brush, is circling in on the ocelot.

No one—from the old trappers in the Valley to his professors—thought Mike would catch anything. He’s proved them wrong. In March 1982 he caught his first male and female ocelots on the Corbett Ranch near Raymondville, and since October he has trapped and put radio collars on six ocelots and four bobcats at Laguna Atascosa, a 48,000-acre national wildlife refuge 25 miles east of Harlingen on the Laguna Madre. It is not an exaggeration to say that he now knows more about the ocelot than does any other human being.

Mike is 25. He grew up in Odem, a small town near Corpus Christi. His father worked at a local refinery until the current oil industry slump; his mother died five years ago; his only sibling, an older brother, is the managing editor of the Kingsville Record. Mike got his bachelor’s and his master’s degrees from Texas A&M, and his cat work will provide the research for his doctoral dissertation at the University of Idaho, where he will go in a year to complete his studies with Maurice Hornocker, a legendary figure among mammalogists for his work with bobcats, mink, and river otters. Mike looks and acts like a country boy. He is six three, with big shoulders, big hands, and big feet, and he moves in long strides and talks in slow mumbles. But he is methodical and determined, and someday he might well join the circle of eminent cat men—the likes of Hornocker, Hans Kruuk (antipredator behavior of birds, social organization of carnivores), John Seidensticker (tiger ecology, conservation strategies for endangered large mammals), and George Schaller (African lion, snow leopard, panda).

Mike’s high level of passion is not unusual among naturalists. He says that as a kid he was always roving fencerows and he raised several nestlings, but he claims it was his pet roadrunner, which he raised the summer after the fourth grade, that sealed his fate. Although his statement is an oversimplification, such a pattern is consistent among ardent naturalists: the powerful attraction before the age of ten to some wild creature. Anyone who has had even a passing association with a roadrunner is aware of its allure. Zipping down the side of a road, craning its neck over its wing, crest at full mast, tail extended like a gangplank, it has a pied-piper, come-hither quality. I know something, it seems to imply, that you don’t. Mike got closer to the roadrunner than most of us do; he met its beady gaze and has never been quite the same.

Mike lives in a cinderblock house in the compound at Laguna Atascosa. Biologists tend to be itinerant and to employ odd paraphernalia; accordingly, his den looks hasty and incomplete—it also looks like the occupant is planning espionage. There’s a five-by-five-foot county map of the Valley, a six-by-four-foot aerial photo taken in 1971 that shows the few remaining patches of brush, a radio receiver attached to what looks like a TV antenna, a number of little bottles with labels like “Cat Scent Number 2,” syringes, vials of serum. Tacked on the wall is a poster of the wild cats of the world, and an inspirational print over Mike’s desk shows a Rocky Mountain setting with a superimposed message that calls for hard work and the pursuit of the impossible dream.

As much as Mike loves the outdoors in general and South Texas in particular, his house is a fortress against the elements. It is a constant battle to keep order (with oriental precision we removed our mudcaked boots each time we entered; otherwise Mike would have had to sweep the place three times a day). He usually keeps the curtains closed and has taped aluminum foil over the front-door transom to reduce glare and heat. More days than not, the air conditioner sputters futilely to hold back the heat and humidity, and on most nights insects beat eerily against the windows.

Mike wants to trap and put radio collars on as many ocelots, bobcats, and jaguarundis as his time and grant money will allow. After he has collared the cats, he tracks them by radio to learn what he can about their movements and associations and, as ecologists say, how they “partition the resource”—that is, how they divide up the territory and the prey available to them. Mike’s days and nights are filled with drudgery and routine. He checks all of his well-scattered traps every morning. Most of them he has jimmied into tight tangles of brush, a task that resembles trying to stick a thumb through a Brillo pad. As traps go, these are commodious (42 by 15 by 20 inches), and they in no way harm their temporary captives. When stepped on by an animal, a spring plate on the floor of the trap releases a pin that allows the door to slam shut. On the back of the cage is a chamber of tight mesh that houses a rooster or chicken, an attractive but unattainable meal for cats on the prowl.

To further enhance the appeal of the traps, Mike dribbles cat lure on the cage. His preferred lure is made by Jerry Thomas, an esteemed trapper from Pennsylvania. Its ingredients are a highly guarded secret that Thomas will no doubt take to his grave, but it smells for all the world like rancid fish sauce. My gorge rose the first time I sniffed a bottle of it, but I became more or less at home with the smell wafting on the breeze in the cab of Mike’s truck —he invariably got a dab of the stuff on himself.

The vehicle Mike drives is a blue four-wheel-drive Datsun with a camper shell. The camper is a shambles: sacks of chicken feed, parts of traps, clods of dirt, tin coffee cans, plastic water bottles. “A wood rat got loose in here the other day,” Mike told me one morning. “It’s great habitat for a wood rat.” The cab has slightly less debris, although the floor mats are mud-crusted and littered with Dentyne wrappers and bottles of cat lure. In the well between the seats (where I sat) are black rubber gloves, binoculars, and oily rags. There’s a compass mounted on the dash. The windows are filthy (a characteristic of the vehicles of mammalogists but not those of birders) and swiped with palm prints, from hasty wipings-off of early-morning dew.

Mike can check most of his traps from the truck, but he has to walk a little way to others. When he does, he carries a dowel, which he uses to part the brush (and alarm any snakes) and to lift open the trap’s door when releasing animals that might bite. He also carries his rubber gloves, which he puts on any time he touches a cage so he won’t leave his own scent. Mike approaches each trap with indefatigable glee, like a gambler approaching a slot machine. Within a few yards of a trap he gets a rush of adrenaline, which ebbs if the trap is empty. It takes about an hour and a half to run the traps when all of them are vacant. If Mike has nabbed a cat, he will spend about two hours sedating it, putting on a radio collar, collecting parasites from its fur, and taking down data: sex, weight, condition of fur, condition of teeth, length of body and appendages, possible lactation if it’s a female, size of testicles if it’s a male.

Sedating an animal is a delicate business. I was with Mike one time when he knocked out a raccoon. The procedure was much the same as sedating a cat, and even on a fairly mundane creature like a coon, the results were swift and dramatic. He poked the animal with a couple of cc’s of the sedative ketamine, using a syringe attached to a long dowel, which he cautiously stuck through the bars of the trap. After about two minutes the coon just crumpled. Mike then put an ear tag on it and took its measurements. He has since stopped going through this time-consuming routine with coons because he was catching so many. Other nonfelines that turn up in his traps include armadillos, possums, and an occasional coyote.

Running traps is one small part of Mike’s regimen. In the afternoons he checks the whereabouts of his cats with his radio (some of them wander on and off the refuge into patches of adjacent brush). He’s figured out that traps seem more attractive to cats the first few days they’re at a new location, and so he switches his traps around frequently. He keeps up on the literature (example: “Environs: Relativistic Elementary Particles for Ecology”). He sifts and sorts through his data—notes scribbled on little tablets in the cab of his truck. His girlfriend, Bonnie Mullikin, who works in Corpus Christi in a hospital pharmacy and sees Mike at odd hours every few weekends, helps him with this paperwork. It is not uncommon for a biologist to bond with a mate who has superior organizational skills and patience.

At 4:45 one morning in February I was standing in the dark on Mike’s front porch waiting for a light to go on in the house and listening to owls. A great horned owl was hoo-hoo-hooing. Another distant one replied every eighteen seconds. A barn owl was calling too—its call is rasping and frantic, unlike the soothing basso profundo of most other owls. I was there to go on one of Mike’s 24-hour marathons, during which he tracks his cats every hour on the hour, endlessly circling through the refuge like a cat chasing its tail. If a behaviorist were observing him, the conclusion would be that Mike was nuts. The purpose of the marathon, which he will repeat once a week for the next year, is to accumulate mounds of data on the nocturnal and diurnal activities of his cats—when, where, and how much they move.

We were at the truck by 5 a.m. Mike fastened an antenna onto the roof by suction cup. Each cat’s collar, a soft white-plastic affair with a floppy antenna, has a small quartz transmitter that sends signals at a specific frequency. Mike calls each cat by the number of its frequency, but occasionally he lapses into anthropomorphism and gives one a name (for instance, he christened number 55, an old bobcat, Lee Roy, after Lee Roy Jordan, number 55 for the Dallas Cowboys). The signals come out of Mike’s radio speaker in the form of strange little beeps that change in pitch and volume as the cat moves around out in the brush. Mike reckons each cat’s activity by counting the number of changes during thirty- or sixty-second periods.

Before we left the parking area he got beeps on numbers 30 (a female ocelot) and 35 (a male). At 5:05 a.m. number 30 was active, her beeps shifting in pitch six times in thirty seconds. I tried hard to translate those beeps into muscle, sinew, rosette-strewn fur, but it was impossible, even in the dreamlike predawn.

The dim overhead light was on in the cab, giving Mike a yellow pallor. Our movements were slow and we yawned a lot; we seemed to be moving not through air but through a clear, viscous liquid. Mike’s hands twirled dials and pushed buttons on his radio. He couldn’t get 61 (a male ocelot). Number 35 faded in and out, prowling right on the edge of receivability. We drove to the first stop, where Mike was able to pick up 35, active, and 28 (a male bobcat), who apparently was still sacked out.

Everything was quiet except for the purr of the truck’s motor, the beep of the radio, and the random growling of our stomachs. As we sped around the refuge, the headlights of the truck fanned out over the road and the edge of the brush, startling rabbits, which popped up and down in the grass like furry little pistons. At our second stop the radio picked up 61, who was active. At the third stop Mike got nothing. At stop four—5:27—he tuned in an active 21 (a female ocelot). The ground fog was so thick that it seemed as though it might make a noise upon impact with the windshield. We caught in the headlights a limping doe with a hunk of meat out of her shoulder.

We finished the first round at 5:32—by now a sliver of moon was hanging just on the eastern horizon—and ran into the house. Mike put on a pot of coffee for me and poured a Coke for himself. We went out again and made the same rounds, but this time Mike got out a couple of times to use his TV-style antenna to pick up the radio signals; it can determine directional movement, whereas the other antenna on the truck, which looks like a lightning rod, picks up only activity level. He figured 35 was on the move. “He’s probably going to find twenty-one. He tends to like her.”

At 6:12 some pauraques (weird, tweedy-brown birds) started calling. Purr-purr-purr-whirrrrrr. At 6:26, as we were heading back to the house, I thought I saw some deer. Instead, it was the refuge manager’s kids running across the field to catch the school bus. By 6:35 there was a fuzzy hot-pink light where the sun would soon be, and around the ring of the horizon distant lights twinkled like pave diamonds. The pink thinned out and spread, the sky lightened, the sliver of moon was powder blue. We passed a gathering of statuesque deer.

We made the rounds five more times. As it got lighter and lighter, more birds —chachalacas, mockingbirds, long-billed thrashers, olive sparrows—started up their characteristic rackets. It was calm and starting to get hot. We tuned in the cats, and all their beeps were as steady as metronomes. Catnaps. On cool days in the winter ocelots will stay active more or less all day, but when summer hits the Valley—about mid-March—they slow down around 9 a.m.

The only thing Mike’s radio won’t tell him is just why his cats move, when they do. That is the most frustrating thing about the pursuits of mammalogists. The objects of their curiosity are so secretive (the exception being the big game animals of East Africa) and so intricately involved with other organisms and various planetary events that mammalogists seem able only to hover over the truth, never quite grabbing it by the throat. Mike of course makes educated guesses—that cats of both sexes move to eat; that males move to find mates (ocelots seem to have more than one) and to secure their territories from other males, which they do by urinating and defecating at specific sites.

Defecation is not random,” said Daniel Navarro, a mammalogist from Mexico, one morning as we stood peering down at a neat mound of scat on the side of the road. This was a particularly fresh deposit. Mike (wearing his rubber gloves in order not to contaminate it with his scent) picked it up, whiffed it, and concluded that it was definitely of the feline variety, which is sweeter-smelling than coyote droppings. He offered me the opportunity to learn the difference myself, but it would be several weeks before I was up to that. He then put it into a plastic bag for later study—he will be able to figure out from the droppings what his cats are eating; he may also be able to differentiate ocelots and bobcats by examining their scat, which would greatly facilitate counting the two species in a given area.

Mike and his fellow mammalogists, like Daniel, are preoccupied with mammalian bathroom habits because in their world of speculation scat is tangible, something they can quite literally put their hands on. Mike has been persistent and lucky enough to observe a male bobcat pacing out his territory, stopping to lift his leg and urinate on a piece of brush jutting a few inches out from the rest of the vegetation at approximately twelve inches from the ground, then moving on to the next jutting twig to repeat the procedure. Mike will get a short paper out of the observation.

The day before one of my visits, Mike had caught a bobcat, which he collared but detained overnight so it could get over the sedative and also so it would defecate. After checking several traps, we got to that one. Mike was as eager to secure another fecal sample as I was to see a cat. As we approached the trap, the bobcat snarled and got up. It was purring, but this was not the long-domesticated purr of a house cat; this was a purr of wrath and vengeance. The cat thrashed about the cage and several times curled back its lips to reveal a handsome set of teeth. It was a beautiful animal, tawny with a few vague spots. Its large paws seemed playful and outsized, like house slippers. It had pointy ears, a longish tail (not bobbed, the way the name implies), and those heavy-lidded, seductive eyes that are the strong point of all felines. At 10:10 a.m. it left its calling card.

Shortly after that, Mike positioned his dowel to lift the cage door, and I sidled over to the rear of the trap to urge the bobcat out. Taking its cue, it exited with ballistic speed and precision. It took a sharp left through the brush, then circled back around us onto the road—bobcats seem to prefer the open road much more than ocelots do—where we went to watch it running, rear end swaying. It had an odd kind of shimmy, which came, I think, from the way its fur rippled as it ran: it was the look of a woman sashaying in a mink coat. Mike went back to the trap for a few moments, then came striding out of the brush holding a plastic bag with five little stogies of bobcat scat. “I have more Baggies of these in my freezer than TV dinners,” he said triumphantly.

One morning in March, while standing in Mike’s front yard, I thought the refuge was going to explode with the chorus of chachalacas. They are big chickenlike birds whose calls, a cacophonous slap-her-back-slap-her-back-slap-her-back, are as persistent and percussive as a Balinese monkey chant. Other birds were yakking too, claiming territories and wooing mates. I even heard the roadrunner’s sad and seldom-performed saxophone run. For joyous pandemonium, it was nature’s equivalent of standing on the corner of, say, Broadway and 42nd, with one poignant difference: as habitat, urban street corners are not in short supply; brush is. I was looking out across the last really prime place in Texas for ocelots. I hadn’t seen one yet, and amid all this exuberance I felt a little forlorn.

Laguna Atascosa is the only expanse of native brush left in the Valley. Its vistas are stunningly wild and quiet. The single thing that pinpoints you in time is the distant outline of condominiums on South Padre Island, and that’s visible only from one end of the refuge. “Brush,” however, is a vague term. South Texans apply it loosely to describe anything from a scraggly patch of impenetrable waist-high mesquite to vegetation like that at Laguna Atascosa—stands of elegant emerald-green ebony trees; anacahuita, greenish black with tissue-thin white flowers; huisache, blackbrush, catclaw, mesquite, and the other acacias, each with its own winsome variation of leaves and blossoms; Spanish dagger, which sprouts huge candelabra of eggshell-white flowers; and cenizo, the ash-gray bush sprinkled with minute lavender flowers—to mention just a few.

Laguna Atascosa’s 48,000 acres form a long rectangle, eighteen miles from north to south, eight miles wide. There is something of just about everything in the way of plants and animals that used to occur in the other 3 million acres of the Valley. Farmland presses up against the refuge’s western boundary; the east is flanked by the Laguna Madre, a vast and shallow bay that more often than not looks like a vessel of shimmering quicksilver.

But Laguna Atascosa is a subtle place, too subtle for some people. Its flora and fauna change incrementally westward from the bay, the result of inches of increase in elevation and changes in soil composition, from the tidal flats to the estuarine pools to the amber cordgrass, then to the brush, of which there are about 8000 acres on the refuge. On the western side is the big lake from which the refuge takes its name. Laguna Atascosa translates to “muddy lagoon,” and, aptly, the lake is often the color of a chocolate soda. In the brush on the south end is a series of resacas, the South Texas name for the severed oxbows of streams that no longer flow but do hold water. About 1200 acres of the refuge are leased to farmers who plant grain sorghum and leave some of the grain and stubble each season for the hordes of wintering geese.

Over this impressive expanse, light makes all the difference. I have seen countless Winnebagos, camper-pickups, Suburban wagons, four-door sedans, most with the windows rolled up, cruising the refuge roads at high noon, when the sun has erased shadow and washed out all trace of color, the occupants’ faces wearing so-what’s-the-big-deal expressions. And I am always tempted to flag them down and tell them to come back at a more propitious time—during the couple of hours at dawn and again at dusk when Laguna Atascosa dazzles.

There are other patches of lush brush in the Valley, but none matches Laguna Atascosa for size. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department manages eleven plots as nesting grounds for white-winged doves, a hunting attraction and hence a boon to the local economy. Along the Rio Grande the brush is even more tropical and the trees reach true forest dimensions. Besides the several unspoiled tracts in private hands, there are the Bentsen–Rio Grande Valley State Park, Anzalduas, the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, the Resaca de la Palm—a prime and as yet undeveloped 1100-acre tract owned by Parks and Wildlife—and the minuscule but exotic Rabb Palm Sanctuary, which is managed by the National Audubon Society. Nearby, the Rabb Plantation, one of the most beautiful Victorian houses in the Valley, stands empty and quiet, on the edge of 35 acres of sabal palm, the last large stand of native palms in the Valley. (Those sentinel palms along the Valley’s highways are imported from Mexico.)

Scattered on private lands are patches of brush that farmers and ranchers maintain as deer leases and also to cut some of the monotony of the landscape. Of these pockets, the largest surrounds La Sal Vieja, an old salt lake west of Raymondville; it is in the hands of several landowners, including Dr. Charles Corbett and his son, Michael. The Corbett Ranch is where Mike Tewes caught his first two ocelots.

One hundred, even fifty, years ago, “monotony of the landscape” was defined differently. Brush in its many manifestations—abundant, harsh, and prickly—dominated the horizon. For the most part, people had neither the time nor the inclination to stand around admiring its beauty, whether it was in the form of an ocelot or an Altamira oriole or an anacahuita. The brush simply stood in the path of progress. Now only about one per cent of the native brush and riverside woodlands remains. Given that we are a species that places a high value on rare things, the brush looks a whole lot more beautiful than it used to.

On March 7 I drove over from Harlingen to meet Mike. It was a lovely spring morning. The first of the wildflowers were starting up—the verbena was rolling out its purple carpet; the huisache and whitebush were in bloom, their fragrances so heady that the smell wrapped around the car and traveled with me. Mike seemed to have recovered from his latest 24-hour marathon. He and Bonnie had had a big meal over at South Padre the day before, and then he’d crashed. Fed and rested and starting to get his summer tan, he had a healthy glow. We headed for the two traps along the main road to the refuge, and I walked back with Mike to see Ted, the one-eyed rooster, who looked big and fat and juicy. But for some reason he had failed to appeal to cats. Once Mike even pulled up and saw two bobcats taking the shade not fifteen feet from Ted’s open trap. We checked the other road trap. Empty. We then headed for the resacas. We walked to what I called the tick trap; it was in tall grass and the ticks did high aerials off the vegetation and onto the pants legs of passersby. It was empty too.

The next trap was amid some salt cedars edging a little pond that looked like an African watering hole—a place to see water buffalo, zebras, elephants, hippos. Mike had put the trap there the day before, placing it semicasually. Mainly he wanted a shady spot for his Rhode Island red rooster until he could decide exactly where he wanted to put it. But even in his nonchalance there was some calculation, because the trap was at the bottleneck of brush that funneled right down to the pond.

As we drove up I was looking at the trap out of the corner of my eye—this was in part because a Harris hawk on a mesquite tree ahead of us had caught my attention. All at once Mike said in a loud, excited whisper, “It’s an ocelot!” and I saw, in the most out-of-focus way, a pair of ears and a spotted brow just above the top of the grass.

We got out of the truck slowly, not slamming the doors, and walked toward the trap. The cat had a collar on, meaning that it was a recapture. It was crouched, not moving, blinking slowly. It squirmed and twitched a little as we approached, but basically it was relaxed. Mike was carrying his radio and antenna, and he flipped through the frequencies until he found the beep that identified this cat as number 35, a young male that had been Mike’s first ocelot capture at Laguna Atascosa.

Mike had recaptured this fellow seven times. He was a rover—Mike had tracked him over a distance of three and a half miles on and off the refuge. In December the young cat apparently got kicked off one part of the refuge by an older, wilier male. Mike speculated that a scar on 35’s lower lip may have been the wound of a territorial skirmish with his older adversary. Mike thought this cat had been courting two or three females on several brushy knolls, and judging by the size of his testicles, his sap was definitely rising.

Mike drove back to his house to get his camera, leaving me with the ocelot. I moved toward him, and he barely acknowledged my presence, just giving me side-glances. He didn’t seem concerned. I eased up closer to the cage, to about fifteen inches, and there I seemed to cross an invisible line that I shouldn’t have. The ocelot began to purr, the message being “Back off.” I did, and he relaxed. Instantly, almost as if he were entering a trance, his eyelids slid closed. Now that I had desisted, nothing seemed more important to him than grabbing a nap.

At that point I had to come to terms with this cat, this event. Mission, if somewhat imperfect, accomplished. Since number 35 was a recapture, he was a little more tinged with civilization than I would have liked, but he did have a relative wealth of history to give him a sense of dimension: a young rogue busily perpetuating his own kind. He was behind bars—I would have preferred seeing one on the loose—but his incarceration was only temporary. He was suffering the brief indignities of being observed, but he was safe at Laguna Atascosa, destined for neither petdom nor coatdom. I figured I could extrapolate his wildness later and for now just take a good, long look. Not anytime in the foreseeable future would I be this close to an ocelot.

The cat had a round face and small ears that were vaguely triangular with the pinnacles rounded; there were velvety white medallions on the backs of his ears. His eyes were large—typical of nocturnal animals—the irises golden, though only when the light caught them. Otherwise they looked black, and of course they were shaded with those heavy, feline lids. The tip of the black nose was satiny and pale, pale pink. The cat seemed to have a permanent pout, like a feline equivalent of Brigitte Bardot.

He was lean and his fur was short and close-fitting. His back was tawny brown sprinkled with black rosettes. These markings made the cat look like he was dappled with light and shadow—excellent camouflage for hiding in the brush. His tail was long, longer than a bobcat’s, and striped with thick jet-black bands. The belly was snowy white with squiggles of black; the fur there was longer and waved into little ducktails. The paws were ashy gray and big—especially the forepaws, which seemed more or less permanently splayed, like a catcher’s mitt. I imagined one swipe of a forepaw smashing all the bones and innards of a cottontail.

When I got within a foot of the cage again, the cat did a tight somersault and then sat up on his back legs, arched his neck, and gnawed at the bars—all of this in slow motion and, so it seemed, for the fun of it. There was no air of rage or panic, no flinging against the bars. The rooster randomly pecked at the cat’s rump, perhaps nabbing a flea. It seemed perfectly at home next door to a mortal enemy.

Mike returned, took a few pictures, and was gleeful that the cat had not only defecated but also urinated, which would leave the cage good and smelly—and attractive to other cats. We watched the ocelot for a few more minutes; as Mike got closer, the cat’s purrs were interrupted by a few throaty coughs, protogrowls. For a moment he massaged his rump on the cage wire and then did another somersault, at which point he seemed to get a little agitated. Mike suspected it was because the cat caught himself with his genitals up in the air and exposed a second too long for safety. Mike got his dowel and lifted and secured the door. The cat sat there for perhaps thirty seconds, and then, with Mike coaxing from the sidelines, he bolted out, took two bounding leaps over the grass, and disappeared into the funnel of brush.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Animals

- Rio Grande Valley