This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

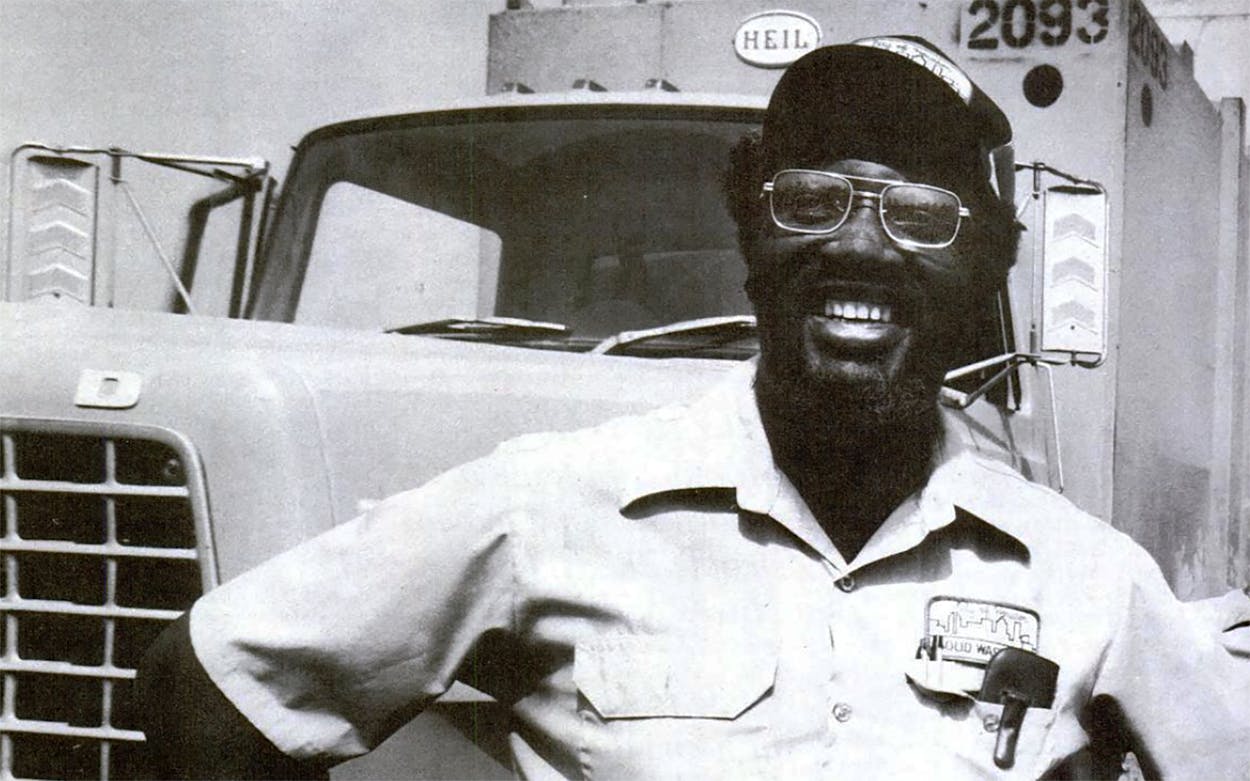

Eloy O’Banion has collected garbage for the City of Houston for nineteen years. He has big hands and powerful arms, stands six-foot-two and weighs 205 pounds. His slightly grizzled beard is full around the chin, thinner on the sides, and his full head of hair shows a little gray. He has a deep voice—he sings bass at his church—and a good laugh. I met Eloy at the Kelley Yard, one of several Department of Solid Waste service centers in Houston. He was wearing gray twill pants from his DOSW uniform, a blue civilian shirt, a DOSW cap, and heavy work shoes. It was hard for us to talk in the yard. At seven-thirty in the morning the place had the smell and noise of one garbage truck multiplied fifty times. I had never given much thought to garbage before. Unlike death and taxes, garbage (unless it isn’t picked up) invites neither eschatological musing nor jaw-clenched anger at the government. It just sits there being garbage, and all we want is for someone to carry it off as soon as possible.

Eloy’s regular truck was out of the yard getting its annual safety inspection. He knew that truck well, was used to its quirks, and he missed it. The foreman found us another, and we climbed aboard and headed for the route. The truck was loud, took up a lane from white line to curbside, and had slow and labored acceleration. Vision from the cab was good, and Eloy could wedge the huge truck into smaller holes in the traffic than I would have thought possible. But then, who’s going to argue with a garbage truck?

Men who work on the backs of garbage trucks are called bumpers. Eloy’s bumpers were Snell Williams and Leo Taylor. Williams, 42, is from Madisonville. He was wearing work clothes, a cap, and dark-rimmed glasses. He is a little pudgy, but it lies on a base of muscle—it is proletarian pudge, not doughy desk pudge. Taylor, 28, likewise country, is from a small town in Louisiana, but he has a more citified manner than Eloy and Snell. He was a little distant. (Eloy told me later that Leo just doesn’t talk a lot unless he knows someone well.) Leo has a long goatee and is on the slender side. His clothes were less readily identifiable as work clothes than the others’, and he was wearing a tan roadster cap.

Our first area to work was Glenwood Forest, a middle-class black neighborhood in Northeast Houston. The houses were nice, five years old at the most. Parked in front of them were new cars, campers, boats—all the outward signs of making it. The bumpers pulled on their heavy gloves, and Snell started the packer motor, the small engine on the side of the truck that powers the blade that packs the garbage. (The packer motor is what makes that growl that wakes you up when the garbage truck is passing your house.) They swung up on the back of the truck and work began. Snell was on the right side and had to engage the packer when the hopper was full of garbage. Eloy thinks this extra bit of work should command a special classification and be worth ten or fifteen cents more an hour. After a block—ten or fifteen houses, twenty or twenty-five cans and bags—the bumpers were soaked with sweat.

When people work together on a physical task, they develop a sense of each other’s capabilities, an intuitive knowledge of what will happen next, and a rhythm that makes their work go smoothly. When the task is something like moving a football down a field, millions of people watch entranced, taking pleasure in seeing a task well done. When the task is getting garbage from curbside to truck, it is easy to miss the skill involved, but it is there.

Eloy knew to an inch where the bumpers were on the back of the 23-foot-long truck. He zigzagged down the street, keeping the truck near the man with the most garbage to bump. He made small adjustments—six inches, a foot—to put a bumper right on a bag, so the man could just reach down and execute a behind-the-back shot into the hopper.

A DOSW driver is given the boundaries of his routes; it is up to him to work out how best to cover it. That leaves some leeway for imagination in the performance of a job that could be regimented totally. “You make your own route. If you don’t pull it right, you be goin’ in circles all day, waste a lot of time and gas for nothin’.” To save turnarounds in tight places, Eloy sometimes turned a corner to get pointed in the direction he wanted and then backed a half-block. The bumpers shouted and whistled when they were ready to move on, and Eloy watched the mirrors constantly. “My bumpers don’t wanna work with nobody but me. I raise sand when they take ’em off my truck and put ’em with somebody else. If they gotta be on another truck you should hear ’em cry.”

Life on the back of a truck is hard and dangerous. A bumper can hurt himself lifting garbage—strain his back, twist his knee, or cut himself on a broken bottle. Or he can fall from the truck if he isn’t careful. A bumper was killed this summer when he fell from a truck and fractured his skull. Even more than the danger, the day-in and day-out lifting, the cumulative weight of thousands of tons of garbage over the years, can wear the strongest man down.

“I like my work,” Eloy told me. “It’s something to do. You’re lookin’ at different people, different things every day. I let my mind wander a little, but mostly I’m steady lookin’ out for cars, lookin’ out for chirrens. I got a responsibility to my bumpers.”

Maybe he looks out for his bumpers so carefully because he put in eight years on the back of a truck. “I wasn’t too particular about drivin’, but somebody told me I’d last longer, so I took the driver job. It’s not bad if you got somethin’ to work with. I take good care of my truck and other drivers know it. It upsets me when they give my truck to a driver that ain’t gonna treat it right, gonna hot-rod it. But when I complain they tell me it’s the city’s truck and I can’t say nothin’ about it.” As he talked about his work his eyes went from mirror to mirror like a man watching a slow-motion tennis game.

Eloy explained garbage. Summer garbage is heavier than winter garbage, what with grass cuttings, melon rinds, and such, but end-of-the-week garbage is lighter than Monday and Tuesday garbage. This was Thursday, and the only delay was a house where someone had moved out and left a huge pile by the curb. Life’s changes generate garbage, and picking it up takes a few extra minutes. Glenwood Forest went quickly. Housewives in bathrobes rushed to the curb to beat the truck; children waved. The bags and cans were right on the curb and there were few stray dogs to overturn cans and scatter garbage. On a garbage truck one becomes very aware of stray dogs.

“Life on the back of a truck is hard and dangerous. A bumper can hurt himself lifting garbage—strain his back, twist his knee, or cut himself on a broken bottle. Even more than the danger, lifting the cumulative weight of tons of garbage day in and day out can wear the strongest man down.”

When we finished, the sweating bumpers got in the cab and we proceeded to our next neighborhood, Settegast. It was poorer, more rural, and racially mixed, with little paint-peeling frame houses and weed-filled bar ditches. People kept chickens and I saw one pigpen. There were lots of stray dogs.

Eloy complained that the neighborhood was hard to work. “People just rides up and down the street, looks like. I guess maybe they don’t work and they ain’t got nothin’ else to do. It makes it hard to pick up. We pick up lots of wine bottles. I think they got a lot of winos out here.” We passed the Clean Hope Holieness Church and a little grocery store with a sign that read OPEN 5 A.M. NO LOAFING. In the dirt in front of the store there was a circle of upended Coke cases, a loafing court for sure. There were a lot of No Loafing signs in the neighborhood. We worked a street named Betty Boop. It was getting hot and I complained, but Eloy said this truck was not too bad. “That ol’ extra truck I drive be next to cookin’ you.”

He knew a lot of people in this area and hollered greetings with explanations to me on the side. “Hi, there. Oh, I’m fine, just fine. (That’s a big man in my church.) Hi. How you makin’ it? (He gives me tomatoes from his garden.)” Almost all the children and many of the adults waved.

The nearest that the bumpers came to taking a break was when they stopped in a yard to drink from a hose and wash their forearms. Even with the traffic and narrow roads we finished quickly. For four hours they had worked at a pace varying from a fast walk to a slow jog, broken by short rides on the back of the truck, and always lifting—fifteen-, twenty-, thirty-pound cans and bags—with more waiting a few yards down the street. Just riding in the cab in that heat was enervating; I couldn’t imagine working in it for hours at a time. An office worker with a bug for fitness might go at that pace for half an hour, work up a virtuous sweat, then catch a little steam, a soothing shower, and a cold beer. Four hours of that kind of work is not exhilarating, it’s exhausting.

We were on our way to the sanitary landfill to dump the morning’s accumulation when a car from the Kelley Yard shortstopped us. A truck had broken down on another route and the foreman wanted our truck to finish out that route. He put another driver in our truck and took us back to the yard in the car. It was just noon when we arrived. The crew would be paid for a full day, a good deal for them. But on some days there are delays with long waits at the landfill or from equipment breakdowns; there is no overtime pay for this.

The yard was quiet now, with just a few foremen and workers from the maintenance shops. Houston is divided roughly into quarters; Kelley Yard at 5425 Eastex is in the northeast. Each quadrant has a service center with from five to seven district foremen. Each district foreman supervises about ten trucks and 35 people—3 per truck, with the extras for sickness and vacations. There are also five foremen on open-bed trash trucks. The three-man crews include a driver and two bumpers.

Where a white man appointed foreman in similar circumstances would go out and buy a half-dozen J. C. Penney short-sleeved dress shirts and two polyester ties, the foremen in Kelley Yard did it up right. They wore wide-brimmed floppy hats, tall heels, vests, and their sharp appearance showed rank just as well as a sergeant’s stripes or a colonel’s birds.

Jack McDaniel is a sharp dresser too, but more staid than the foremen in the yard. He was wearing a lightweight plaid suit. He is bespectacled and trim, a likable man, known in his private life as a wicked banjo picker. McDaniel is director of the Department of Solid Waste Management, head garbageman, so to speak. “No other city department interfaces day in and day out with the public like Solid Waste,” McDaniel told me. “Twice a week and every other Wednesday, people see their garbageman. We have more personal contact with the public than any other city department—and garbage is very personal. You can look at people’s garbage and know a lot about them.”

The average citizen may have contact with the police every two or three years; if he is lucky he will never have to call the fire department; but he counts on the fact that the bag he leaves by the curb in the morning will be gone in the afternoon when he comes home. If it is gone, he doesn’t take much notice; if it’s not gone, he complains.

McDaniel catches the flak that comes to all public officials, but has little hope for the compensating glory that falls to a police chief when a big case is cracked or to a fire chief when a major blaze is well handled. Even the men on the trucks are honored by the Chamber of Commerce “Crew of the Year Awards.” McDaniel probably has moments when he envies his employees their uncomplicated duties. The best he can hope for is silence. A phone that doesn’t ring is as near as McDaniel gets to a “thank you” from the citizens of Houston.

The morning I met McDaniel, his secretary was on sick leave, and he was answering his own phone, mostly taking complaints. “The Department of Solid Waste,” he announced into the phone. Sometimes he had to amend it to “Garbage Department” to assure the caller that he had the right place. People are often reluctant to embrace euphemisms. McDaniel’s office was cluttered with reports and correspondence. Technical works on the fine points of garbage filled the bookcases. A huge map of the city hung on one wall. McDaniel was harried, probably more comfortable with the mechanical stresses of civil engineering than he is with the emotional stresses of public administration. The department was having trouble doing its job because maintenance troubles were keeping garbage trucks off the streets.

Foremen were unhappy because three or four of their ten trucks were out of service. Citizens were unhappy because their garbage often went uncollected. City councilman Frank Mann was unhappy because he believed that McDaniel had manufactured the crisis to get council approval for side-loading trucks that McDaniel wanted to order. The leadership of the union that represents Houston’s garbagemen—Local 1550 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME)—was unhappy because the side-loaders could be manned by two-man crews.

The back-loaders the department now uses require three-man crews. Union leadership also maintained that the side-loaders were more dangerous. Eloy had told me, “On side-loaders you gotta muscle your can up higher. That makes more work. There are more accidents on side-loaders, I think. We can’t leave garbage on the ground if we drop it, so bumpers have to push it in with their hands if it’s startin’ to spill instead of let it fall and pick it up. They’d get their hands caught by the blade. Too, the bumper on the side away from the hopper’s gotta run all the way around the truck to bump his cans.” Snell and Leo are worried that they might be cut to two-man crews.

McDaniel told me he had sworn that if two-man crews were used it would be voluntary and premium wages would be paid for the extra work. McDaniel wanted the side-loaders because they have four tires fewer per truck—there had been budget overruns for tires and attendant axle repairs—and have four cubic yards more carrying capacity than the back-loaders. We talked on a Wednesday. The day before, the council had authorized the purchase of fifty side-loading trucks, but McDaniel had taken lumps getting his side-loaders.

He has been with the Houston department for seven years. Before coming to Houston he was director of public works in Corpus Christi. He spoke with longing of sailing his Sunfish on Saturday mornings in Corpus Christi Bay. There’s no time for sailing in Houston, but he can see a pension down the road, so he’s hooked.

When we left city hall for Kelley Yard, I put some newspapers in the back of my truck, and McDaniel fussed over them. I told him they would be all right, and he said that he wasn’t concerned that I would lose my papers, he was worried that they might litter his city. Driving up IH 45 we passed a city bus, and he mentioned that the Houston Chronicle ran a box score of out-of-service buses on page one every day. McDaniel said he hoped they never got around to doing the same for garbage trucks.

The administrative offices at Kelley Yard are in a yellow-brick and government-green building. A cluster of supervisors in the reception room admired McDaniel’s suit, and he kidded that his clothes looked good because he was the head garbageman and had first pick on what came off the trucks.

It was easier to picture John W. Daut, McDaniel’s administrative assistant, hanging off the back of a truck. He is beefy, running to paunch, and has a bushy gray moustache. Not only did he eschew coat and tie, he let his shirttail hang out. After seventeen years in the garbage business, he is philosophical about public gratitude. “It’s like last night, my wife asked me after supper, ‘Was everything all right?’ I told her, ‘I didn’t complain, did I?’ If we don’t get complaints, we’re doing okay.” He transferred to the department from parking meters when all DOSW supervisors were white and came from outside the department. Now all promotions are from within, and out of a thousand employees in the department, there are 33 Anglo men and 28 Chicanos, mostly in maintenance. A few women are employed in secretarial and clerical positions, and a few have worked short periods in collection in the past, but they didn’t stay long.

Operating expenses for DOSW are $21 million per year, less capital purchases. In 1978 the department collected 401,100 tons of garbage (Daut said with a sly grin, “Who’s going to check me on that?”) and 197,577 cubic yards of heavy trash—old furniture, stoves, refrigerators, and such. The astonishing thing about those yards and tons is that the department collects only about 30 per cent of the solid waste generated in the city, all that from curbside residential collection, small businesses, and small apartment complexes. The rest—from large apartment complexes, industrial installations, shopping centers, and residential alley collections—is picked up by private contractors.

The average DOSW driver earns $254 each week, the average bumper $240. Fringe benefits add 35 per cent to this, and there are ten and a half holidays a year. Sick leave accrues at one and a quarter days per month, necessary in a job with an accident rate that approaches that of mining. (But if your mother told you that you’d catch something if you played by the garbage cans, she was wrong. Bacterial and viral infections are uncommon; John Daut says, “In seventeen years here, I can’t remember a single case of hepatitis.”) Eloy earns a base pay of $245.90 a week, plus longevity pay of $34 every two weeks. He has accumulated more than 200 days of sick leave and 84 vacation days. He intended to take some of those vacation days this fall, mostly to do some yard work, plant a winter garden (after he consults with an old aunt who is a great gardener), and cut down a pine that has died in his back yard. “I don’t have much use for pines. You can’t grow nothin’ under ’em. Those ol’ pinestraws kill your grass.”

The gray skeleton of the pine loomed over his neat white house just outside the Houston city limits, ten miles from Kelley Yard. It is further away in spirit, a clean, calm contrast to the bedlam of the yard, a reaching back to a country rearing. Eloy was born and raised in Wiergate, a rural community in Newton County near the Louisiana line. He quit school after the tenth grade. His father died when he was eight years old and his mother was sick and couldn’t work; he had to help out financially with a younger sister and brother. He came to Houston, lied about his age, and went to work in a shipyard. From the shipyard he went to Hughes Tool and stayed nine years as a common laborer. Laid off there, he went to work in the DOSW and refused to return to Hughes when the callback came. He was 27 years old. The security of a city job was irresistible.

Security is a big thing for city employees. Even the O’Banions’ house feels secure. The front porch was covered with dozens of potted plants. His green Ford pickup sat in the driveway. The living room was full of knickknacks, pictures of family, religious plaques, a set of encyclopedias. The television was on in the adjoining den. “I like sports. I looked at the Saints and Oilers preseason this week. I’d like to go to the games, but just gettin’ out there is a problem. Football and boxin’, that’s my two sports, then basketball. I used to go fishin’—catfishin’—some, but bait and all got to costin’ so much that I didn’t even buy a license this year. Maybe I’ll go fishin’ when I take my vacation.”

Myrtle, his wife of “oh, twenty-six or -seven years,” works occasionally in private care of sick people, and when she does he helps out some with cleaning up, but he feels that the man’s place in a household is at the head. They have five children, four daughters and a son, aged 25 to 16. “I tried to get my boy on at the department, me and Mr. Daut both,” Eloy told me. “But he didn’t go for it. I think he had somethin’ else in mind.”

Most of the family’s free time is taken up by Creston Baptist Church. “Some Sundays we spend the whole day in church. We go at eleven and three and we’re back for a seven o’clock service. After I went back to the church I wanted to bring up my chirrens in the church. They still church.”

“Church” said it all. “I’m church. I used to like my beer, but I done come in from that field. I don’t mind if a man drinks a couple of beers, though. I don’t see nothin’ in the Bible about not drinkin’. It just says don’t get intoxicated. Same way with smokin’. I smoked thirty-one years and just got tired of foolin’ with it. Said one day, ‘When I finish this pack, I smoked my last cigarette.’ ”

“Church” is how Eloy classified the men at Kelley Yard too. “McLemore, he’s church.” I had heard about a possible crap game in the maintenance barn. “I don’t know about that, but some people down there are church, and they hold little prayer meetings.” He gave the same kind of reply to a question about drinking or smoking dope on the trucks, a matter of some concern to management because of the potential for accidents. “Not on my truck. I don’t know about anybody else.” He wasn’t telling anybody’s secrets.

Not that he saw no evil. “The Bible says in the last days sights will be seen, and we’re sure seein’ sights now. It seems to me that people done lost their respect. They don’t treat folks like they want to be treated. My wife’s tryin’ to have flowers and there are chirrens around here throwin’ balls. You gotta steady fuss at ’em, and sometimes their parents gets mad. You gotta put up with a lot.” This may have been less the plaint of a Christian in a pagan land than that of a rural man in the city. City living seemed to disagree with Eloy, even in this quiet neighborhood. “I like it down around Huntsville where my wife comes from. Maybe we move down there when I retire.” In the meantime, he had bought his house ten years ago, and the notes were only $130 a month, not too much of a strain, especially with the department working overtime.

Overtime comes on Saturday and Sunday. It is a new development, traceable to equipment problems. There was formerly little overtime available except on the small-animal trucks, the “dog trucks.” Eloy was offered a dog truck a few years back, but refused it. The DOSW operates four small-animal trucks, which picked up 12,460 small dead animals last year. There is also one large-animal truck that collected 502 large dead animals. That’s a lot of dead horses and cows within the Houston city limits. Eloy told me that they haul dead animals away from the city zoo too.

On Friday morning I was back at Kelley Yard with Eloy, again waiting for a truck. He had heard that his regular truck was back in the yard but not yet inspected. When we were assigned a truck, he worried over it, checking tires, oil, coolant level. Everything was all right, but he discovered the truck didn’t have enough diesel to make the whole day and for some reason there was none in the yard. We had to go to a facility on the other side of the Ship Channel to fuel up. The trip put us forty minutes in the hole for the day. Eloy didn’t know why there was no diesel in Kelley Yard. “The public doesn’t know some of what we go through.”

Our first Friday neighborhood was Greens Bayou, by IH 10. There were some trailer parks, small apartment buildings, and, along Market Street Road, a lot of small businesses, many of them taverns. I wanted to bump a few blocks to find out how the work really felt, which was impossible while riding in the cab, but beer joints with six cans full of beer bottles was more reality than I wanted.

We saw a slat-ribbed dog, like a hide-covered xylophone, sniffing at a can on Market, but he fled when we drove up. A little later, as we pulled out of a side street, the same dog knocked over a can in front of Marty’s Ice House. What fell had to lie there. It wasn’t the bumpers’ job to pick it up. A lot of bottles had spilled out. “I ask these beer j’ints to tie their bottles up in bags, but they get real salty.”

Loose bottles in a can are a nuisance, but broken bottles in plastic bags are a hazard. O’Banion once had a bumper cut his arm on one. “Blood was just gooshin’ out. We called an ambulance, but I believe he’d of bled to death if a lady there hadn’t taken him to the hospital. A lot of those accidents are because of rushin’ or carelessness. I never been hurt but once. I was ridin’ on an open-bed trash truck. When the driver took off I fell back and tried to catch aholt and cut my hand.”

Leaving the Market route, we saw an old man on a three-wheeled bike picking up aluminum cans by the roadside. I commented that they must be worth about twenty cents a pound. O’Banion corrected me, “Twenty-four. I used to pick up cans just for the exercise, but I quit about six months ago. I see old mans pickin’ up cans to help out their pensions. They need that money. I got a job. It’s hard for them to make it if they don’t help out their checks.”

When I looked down Corpus Christi Street, I knew I’d found my bumping place. (Two days before I would have seen trees, cars, houses; now all I saw was cans and bags.) It was residential, just one or two cans per house, as close to easy as bumping gets. I borrowed Williams’ gloves. After two or three bags the sweat broke out on me. I was riding the right-hand side, so I had to throw the lever to engage the packer motor when the hopper was full. The smell was a lot fiercer on the back than it had been in the cab. Some of the plastic cans were so beat-up that pieces came off when they were lifted. Aha, there was a hops-head—a can full of beer bottles. I dumped a metal can with some kind of liquid in the bottom. There was something in it that looked like rice. The rice flailed around—it was maggots. I picked up a torn bag and cursed all people who let their dogs run loose. An ant crawled off a can and bit my arm.

In a couple of blocks I was puffing. I felt I was holding the crew up, so I returned Williams’ gloves and reclaimed my notebook, which he’d been holding for me. My forearms were stinking from the stuff that had run from the bags and cans. The only thing of value I had seen was three deposit bottles in the muck at the bottom of the hopper. I wouldn’t have retrieved them if they’d been worth $10 apiece. O’Banion said he’d never found anything worth much. “Just one dollar one time in all the time I was bumpin’.” Our bumpers disclaimed any interest in scrounging, but after our first day’s run I noticed Williams with a pair of almost new shoes and a length of copper pipe. McDaniel had told me that he had no objection to salvaging things, just so they weren’t running full-scale businesses on the side.

My first question back in the cab was whether the men ever got used to the smell. “You can sure tell if someone been fishin’ or catchin’ crabs. Or sometimes someone puts a dead dog out in the can and it gets in the hopper and you can’t put it back. That smell stays. You got to live with it.” At the end of the street, we stopped for water at a gas station, and I washed my arms. Eloy had told me that the body got accustomed to bumping after a couple of days. It would take my nose longer.

The rest of the day I was content to ride in the cab and talk trash with O’Banion. Knowing he was steady and reliable, I asked if he had been offered a foremanship. “Two times. I turned it down. I know I can do this job well. If I’m foreman and the mans in the yard don’t do me right, I can’t do my job right. I’d rather stay where I am and do my job well. These youngsters, they just outta hand. They oughta be more stricter with ’em. As a man get hired they should give him his bylaws so he knows what to expect and can take it or leave it. If a man don’t take care of his job, he won’t take care of his family.”

After we finished our second neighborhood we drove the eight or nine miles to the Browning-Ferris McCarty Drive sanitary landfill, where the city pays for dumping rights. When we arrived, trucks—private, city, and Browning-Ferris—were backed up all the way out of sight around a curve. They told me that this was about a sixty-truck line—not too good, not too bad. On rainy days they had waited as long as seven hours to dump. A local television station filmed the lines that day, much to their satisfaction. Eloy thinks the city trucks should have their own line.

As we waited, we talked. Williams asked if I’d ever been here before, and I kidded him that the sanitary landfill is not on any list of tourist must-sees for Houston. What strange things had they picked up? All they could come up with was “dead dogs.” Perhaps it took tonier neighborhoods than we had worked to generate exotic garbage; or perhaps like customers to a jewelry store clerk, after a while, all garbage looks the same to a garbageman.

Did they want to stay on at the department? Williams answered, “As long as I can. It’s a fairly decent living, but things are going up. We get four-somethin’ every two weeks, they take out, and you got three-somethin’ left. My kids want things like the other kids have.” Leo was not so sure about staying on. “I don’t know, it’s hard to say right now. I don’t see who’d wanna make a career outta bumpin’ garbage. This job here is not as important as police work, but it’s harder.” That statement was as close as any of them came to placing the job in a wider social framework. Basically, they are not men given to long, long thoughts about their job. They just do it, they don’t philosophize about it.

They had seen on television that garbagemen in some cities earn $17,000 or $18,000 a year. They wondered if the Teamsters would be more effective than Local 1050 of AFSCME. Snell had a union card, but Leo had let his go because he felt he wasn’t getting anything for his dues. Eloy had given his card up two or three months before, after the truck he was driving had a flat and he was held up several hours while a new tire was being mounted. The holdup threw them late. Eloy felt that the union had been ineffective in taking care of things like that. He was also uncomfortable with Wilma Oliver, the union representative. “She just can’t understand a man’s problems,” he said. But I got the impression that the union doesn’t loom large in their considerations one way or the other.

As we talked we were inching farther into a wasteland of cans, bottles, old tires, organic garbage, broken toys, castoff clothes—all the detritus ground off by the wheels of progress, the whole mess festering and fermenting under an August Houston sun. The smell was last week’s cat food to the tenth power. Bulldozers plowed hills of filth around. A tractor-trailer rig was stuck in the muck and a bulldozer was pushing with its blade on the back of the trailer to help the rig out. A city truck dropped into a low place and spun its wheels. “Some of these city trucks couldn’t pull a hair out of your head,” Snell said. The noise was piercing—bulldozers growling, truck engines straining, wheels spinning, metal grinding against metal.

The place made me uneasy. Two-thirds of the horizon was garbage, the other third pine trees that are bladed down as needed to expand the dump. It was a vision of hell in a rustic frame. The Houston afternoon provided the heat; all that was wanting was flames. I was relieved when we left.

Our truck weighed 55,000 pounds when we went in; now it weighed 32,400 pounds. Leo and Snell had picked up twelve tons of garbage by hand. On the way out, I counted nearly a hundred trucks. The city crews hollered and kidded with us as we passed, making the most of a bad situation.

Even someone who is not church should be moved by these circumstances to observe that “the workman is worthy of his hire.” Schoolteachers, when they are feeling aggrieved, invariably fix on the garbageman’s wages. “Here’s a garbageman in Houston who makes almost fourteen thousand dollars a year, and the average Texas schoolteacher earns just eleven thousand.” If you feel teachers are underpaid, you might have a point. If you feel that garbagemen are overpaid, you can apply at the Department of Civil Service Employment at 702 Preston in Houston. You won’t need a college transcript and there is no test. If you’re really lucky, you may get to bump for Eloy O’Banion.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston