This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue with the headline “The Pride of Northeast Texas.”

When Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim died this summer, at age 89, he left behind an oddly lifelike tribute to himself: a huge fiberglass replica of his own head, topped off with a pilgrim’s hat, complete with shiny buckle. Sitting atop a white-columned pavilion in front of a poultry distribution facility, the landmark reaches a total height of 37 feet. It’s one of the first things you see when you take the main road into Pittsburg, the northeast Texas town where Pilgrim founded Pilgrim’s Pride, the multinational poultry business that made him a fortune.

Folks call it “the Bo head.” Others know it as “the Hat.”

“You know, that hat was on top of this building at one time,” said Jim Seale, who was nursing a coffee the other morning at Herschel’s Restaurant, a short-order place five miles south of the wide-brimmed bust. Seale was correct: Pilgrim’s signature hat spent about three decades on the roof of the building that now houses Herschel’s. Back then, it was the site of a fried-chicken joint owned by Pilgrim. After he shuttered the place, in 2001, he commissioned the Bo head and put the hat on top of it. “He built the head to fit the hat,” Seale said. “Because the hat was already done.”

Pilgrim was nothing if not enterprising, agreed Seale and his tablemates, a group of self-described old fogeys who get together most mornings. Fred Cook, the fogey sitting to Seale’s right, had the long sideburns and thin, white pompadour of a retired rockabilly singer. A member of the Pittsburg City Council, he moved here from upstate New York in the mid-eighties after his father began raising chickens as an independent contractor for Pilgrim’s Pride. “Come down to Texas and work in the chicken barns,” his father had told him. Cook did but quickly realized that the poultry business wasn’t for him, so he joined the Pittsburg Police Department instead.

Cook took one more swig from his cup. The Pilgrim talk had waned. “If you want to follow me,” he said, “I’ll show you where he’s buried.”

Cook drove a quarter of a mile north. His little dog, a shih tzu mix introduced as Killer but really named Max, accompanied him. Cook hooked a right, then another, entered Rose Hill Cemetery, and got out at the far side of the property. Max stayed in the car. “He’s over here by Bodie,” Cook said, pointing toward a black headstone engraved with the likeness of a muscle car. It was apparently an early seventies model Chevy Nova, which he thought was what his late friend Bodie used to drive.

Pilgrim’s grave didn’t seem to be in the vicinity. “Well, I’ll be a son of a gun,” Cook said. He looked around. Birds sang. Max yipped from inside the car. “Dang dog,” he muttered. “Ain’t that something else? I thought it was funny Bo was buried next to Bodie, all the way in the back. We probably walked by his grave about fifteen times already.”

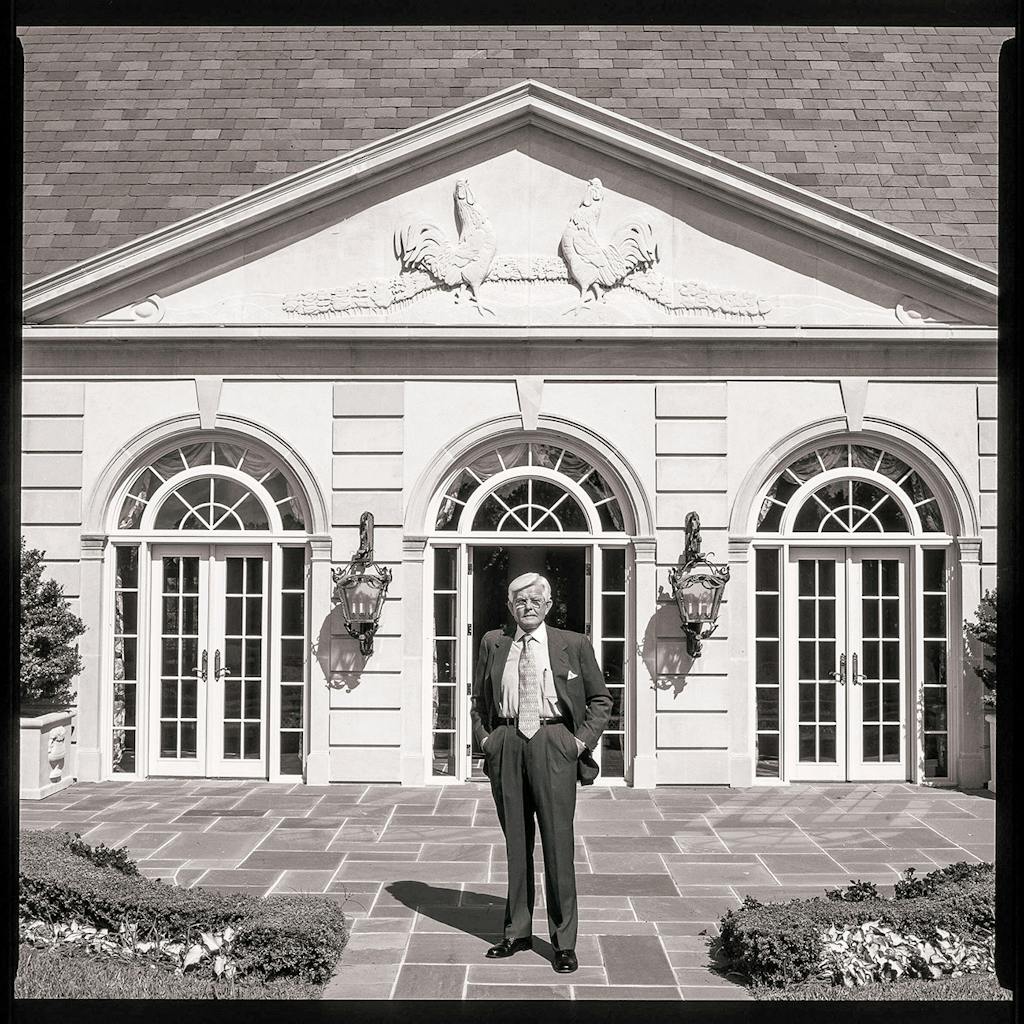

Elsewhere in Pittsburg, known to some as “Bo’s town,” it’s not so difficult to find evidence of Pilgrim. He funded new parks and built a downtown Prayer Tower that chimes hymns on the hour. And then there are the monuments. The pavilion that supports the Bo head also shelters a bronze statue of Pilgrim reading the Bible to his pet chicken, Henrietta. Though a silhouette of Pilgrim is no longer used as the corporate logo for the poultry empire, it does adorn the bank he founded here, as well as the gates in front of his mansion, which he called Chateau de Pilgrim and others nicknamed Cluckingham Palace.

Pilgrim also achieved a certain amount of fame beyond northeast Texas with his TV commercials, which promised that he would “never sell a fat yellow chicken,” but also infamy for his company’s record of environmental violations, and for the time when he handed out $10,000 checks to lawmakers on the floor of the Texas Senate as legislators considered a workers’ compensation bill he had an interest in. In 2008, Pilgrim’s Pride filed for bankruptcy protection, and the company eliminated thousands of jobs, which hit Pittsburg pretty hard. A year later, Pilgrim sold a majority stake in the business to a Brazilian outfit, and in 2011 the company’s headquarters flew the coop to Colorado.

Although Pilgrim’s Pride still has a presence in town, the so-called Texas Miracle has more or less bypassed Pittsburg and surrounding Camp County, where the number of jobs stubbornly remains about 10 percent lower than it was a decade ago. Folks are optimistic about Pittsburg’s future, though. This summer, the downtown feed-and-seed store, where Pilgrim’s Pride got its start in 1946, reopened as a brewpub and dance hall, a sign of the transition from being Bo’s town into something new. As for Cook, now retired from the police department, he and his wife are considering a move back to New York to be closer to grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

At the cemetery, wet grass clippings stuck to Cook’s white, Velcro-strapped sneakers as he wandered between rows of monuments, reading names. “My old chief is buried out here somewhere,” he said. One of Cook’s drug informants from his days working the streets was interred in a pauper’s grave. “We know who did it,” he said, of her killer. “Can’t prove it, though.” The town’s police officers pooled their money to buy the woman a headstone.

About eighty yards away from where his search began, he finally arrived at Pilgrim’s burial site. A colorful bouquet of roses and sunflowers lay upon the earthen mound. There was no headstone yet, nor had the grass begun to grow.

“Ol’ Lonnie ‘Bo’ Pilgrim,” Cook said. “For a guy that . . . ” his voice trailed off. “It’s not a fitting place for a guy of his stature,” he said. But he appreciated that Pilgrim was laid to rest among the people he knew best.

Cook walked back to his car, then paused and looked across the headstones. “It always seems so quiet, doesn’t it?” he said. The birds were still singing, but Max had stopped yipping. “Yeah, I know a lot of these people. They come and go.”

Cook drove away. A minute later, he was back. He had returned with a parting gift for this reporter: a CD recording of himself singing Elvis Presley songs and a few other oldies. He used to work as an Elvis impersonator and still entertains at nursing homes and assisted-living centers, though he no longer wears the tight jumpsuits. “I packed them away a long time ago,” he said. “My hair fell out and my stomach got big.”

To make sure that the disc was functioning properly, he fed the CD into his Ford Escape and hit play. Max sprawled across his lap. Sitting in the driver’s seat, not far from Pilgrim and the pauper, Cook quietly listened to songs performed by a younger version of himself. He sounded a lot like the King.