“Are you, like, serious?” exclaims the preppily dressed Stacey High. “Have you ever gotten a good look at her? Marie is, like, gorgeous! In high school she was one of the most mature girls I had ever met. I thought, ‘Wow, if I hang around her, she’ll keep me motivated, help me act a little more serious.’”

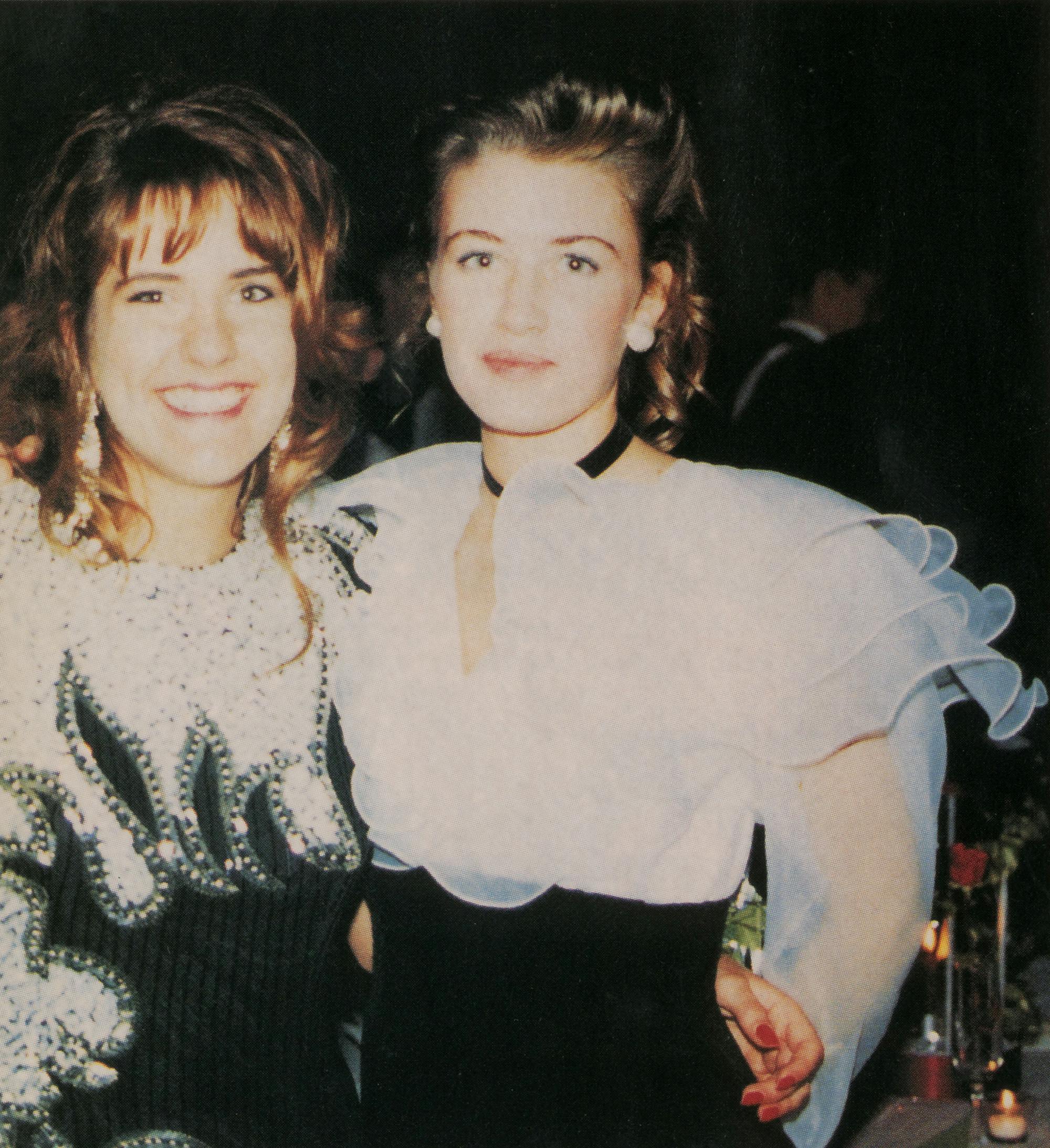

Stacey stares at a prom photograph of her and Marie Robards, her best friend during her senior year in high school. “We used to do everything together. I mean, everything. And then I find out that she has gone off and poisoned her dad for this totally crazy reason. I mean, how weird is that?”

It is the kind of murder story that fascinates people because it is filled with such familiar, seemingly innocent characters: teenage girls coming of age in the suburbs, their lives driven by adolescent insecurities, daydreams, and startlingly mercurial moods. In February 1993 Marie Robards, a tall, striking Fort Worth 16-year-old, pulled off what a prosecutor called the perfect crime, murdering her 38-year-old father, who was divorced from her mother, by slipping a spoonful of the poisonous chemical barium acetate into the refried beans of the take-out Mexican food he was eating one evening. The autopsy found nothing unusual. To detect certain poisons and less common chemicals such as barium acetate, a specialized $150,000 machine was required, which the Tarrant County medical examiner’s office did not own. The coroner attributed Robards’ death to a heart attack.

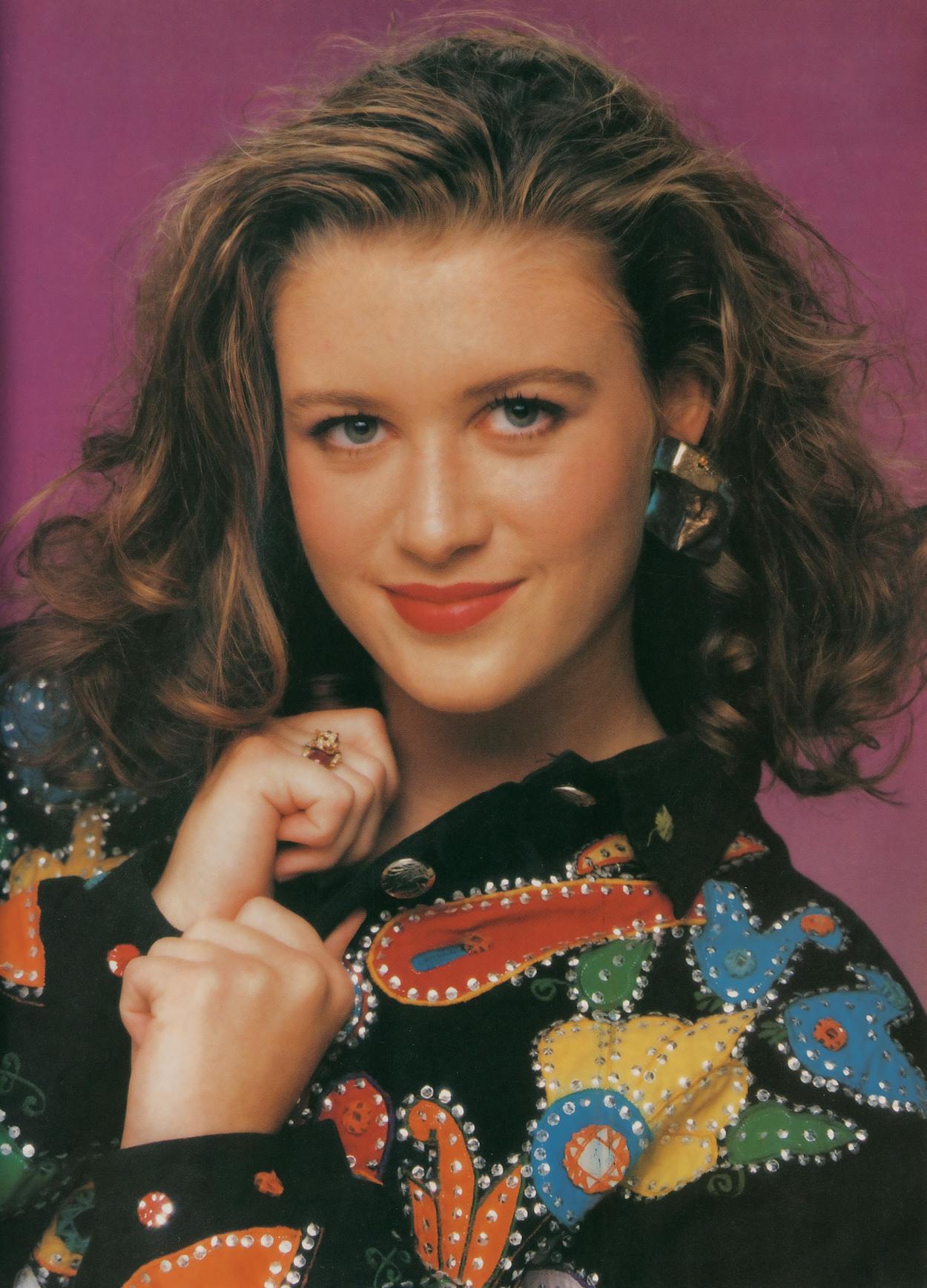

For nearly a year, Marie told no one about the crime. She was an excellent student, reserved but polite, the kind of girl who never acted impulsively, never stayed out too late or had too much to drink at parties. She didn’t date much, but the boys couldn’t take their eyes off her long legs and deep brown eyes.

Then, one night in January 1994, during her senior year of high school in the Fort Worth suburb of Mansfield, Marie was studying Shakespeare’s Hamlet with Stacey, one of the school’s most popular girls. According to Stacey’s version of events (which Marie has never denied), Stacey turned to her favorite part of the play: the soliloquy of Danish monarch Claudius, who poisoned his brother (Hamlet’s father) to gain the throne. In her most dramatic voice—which was only slightly affected by her Texas drawl—Stacey recited Claudius’ agonizing speech in which he wonders if he can ever repent: “My fault is past. But oh, what form of prayer/Can serve my turn? ‘Forgive me my foul murder?’/That cannot be, since I am still possessed/Of those effects for which I did the murder . . .”

“Isn’t that cool!” Stacey said. But when she looked across the table, Marie had turned pale and her hands were trembling.

“Stacey,” Marie asked, “Do you think people can go through life without a conscience?”

Stacey answered, “Well, how about the kind of person who can look somebody in the eye and kill him in cold blood?”

Staring at Stacey, Marie got out of her chair, backed up to the wall, then collapsed to the floor and began to weep. “Marie, what’s the matter?” asked Stacey.

“Guess,” Marie whispered.

Stacey thought of the worst predicament that she could imagine a fellow seventeen-year-old girl could be in. “Oh, my God, are you pregnant?”

“No.”

“You wrecked your grandparents’ car?”

Marie shook her head no.

Almost jokingly, Stacey asked, “Well, um, you didn’t kill somebody, did you?”

Marie’s body heaved with sobs. “My father,” she said. “I poisoned him.”

For weeks Stacey tried to keep Marie’s story a secret. “When you’re in high school, it’s, like, so important not to betray your best friends,” Stacey later told me. But tormented by guilt and bothered by the idea that Marie might be a far different girl from the one she knew, Stacey eventually contacted the police. Eight months later, after barium tests were run, Fort Worth police officers arrived in Austin, where Marie was a freshman at the University of Texas, still lovely, still studious, still seeming so harmless. At the Austin police station, she quickly admitted to the killing. As if hoping this pale, gentle teenager would explain away her crime, a detective asked her over and over if she had been abused by her father. “No, sir,” Marie said. The detective asked if Steven Robards had ever done anything to her that he shouldn’t have done. “No, sir,” Marie said.

Then why, asked the detective during the tape-recorded interview, did she put the barium acetate in the refried beans?

“Because it was the only way I could go back home,” Marie said.

“Who did you want to go back home to?” the detective asked.

“My mom,” Marie said in a soft, distraught voice. “I wanted to be with my mom.” Marie’s mother, Beth Burroughs, a woman as tall and beautiful as Marie, had remarried and was living in Granbury, outside Fort Worth. In a confession that Marie typed herself on a word processor at the police station (in her senior year of high school, Marie had won her district’s University Interscholastic League competition in keyboarding), she wrote, “I just wanted to be with my mom so bad that I would do anything to be with her.”

The reactions to Marie’s arrest in October 1994 ranged from sheer disgust to muddled sympathy. Mitch Poe, the young Tarrant County prosecutor who would try the murder case, called her “society’s worst nightmare: a girl who kills her dad.” Co-prosecutor Fred Rabalais, Jr., described her as “a remorseless predator,” another example of the growing number of teenagers who use violence to solve their problems. But others saw her as Texas’ Lizzie Borden, who despite her gruesome act seemed to be such a pleasant and proper girl. “I know this girl does not have a criminal mind,” said Steven Robards’ father, Jim, who was close to Marie. “For reasons only she will know, she committed this one-time act. But I know that’s all it was—a one-time act. I have to say, I don’t understand what good a penitentiary sentence will do for a girl like Marie.”

Before Marie’s trial, which began this past May in Fort Worth, her defense attorneys arranged for her to give an interview to the Associated Press, in which she said she never intended to kill her father but only wanted to make him sick so she could live with her mother. “I never thought anything through. I didn’t realize what I was doing,” she said. “I knew I had done something very, very wrong. But I did not think of myself as a criminal.” Her comments, of course, didn’t shed light on what made her suddenly careen out of control. It’s unlikely that Marie herself understood the forces at work then in her life. But for many who followed the story, the poisoning of Steven Robards was a twisted parable about the consequences of divorce, when children often must navigate their own way while parents are preoccupied with rebuilding their lives. “You know, there are times when we all say we hate our parents and wish we never had to see them again,” said Stacey, whose mother and father are also divorced. “But kill one of them? Until now I just never thought it was imaginable.”

In Fort Worth during the seventies, Steven Robards and Beth Lohmer were high school sweethearts. Steven, whose father ran a small insurance agency, was one of the best-looking boys at school at six feet four inches tall with dark curly hair and a lean, muscular body. The statuesque Beth was the president of her school’s National Honor Society and a standout athlete on the track, volleyball, and basketball teams. In 1974, when she was eighteen, she married Steven just after he entered the Navy for a four-year tour of duty. Two years later, Beth gave birth to their only child, Dorothy Marie Robards. After Steven served at Navy bases in San Diego and Florida, the young family returned to Fort Worth. The relationship was a rocky one, and in 1980 Beth separated from Steven, taking Marie with her.

In the only interview she has given about the events surrounding Marie’s life, Beth told me that she became disillusioned with Steven when he began having episodes of depression soon after their wedding. “Steven’s behavior had always been a little erratic, but I was a naive Catholic girl, caught up in this whirlwind teenage romance with this suave guy,” said Beth, an outgoing and remarkably frank woman. “But there came a point when I didn’t know how to act around him anymore. He became jealous. He had temper tantrums. He couldn’t hold onto a job. And then there were times when he would get so tired and feel everything was so bleak and dark and that nothing was worthwhile.”

By 1981 Beth was already remarried to a man named Frank Burroughs, a former Navy petty officer she had met when Steven was stationed in Florida. “There was nothing between Frank and me back then,” Beth said. “We were just friends.” Burroughs eventually found a job as a police officer in Granbury. Recently divorced and the father of a young son, he was a strong-willed, protective figure who liked the idea of being a father to Marie, who was only four years old when her mother remarried. As Burroughs said proudly on the stand at Marie’s trial, she called him Dad and Robards Steven-Dad.

Marie saw Steven only once or twice a month in Fort Worth, where he lived in a one-bedroom apartment. Ironically, however, the problems that began to appear in Marie’s adolescence did not concern her father at all. They involved her stepfather. “When Marie has described those days, I have sensed there was some jealousy or possessiveness about her mother’s relationship to Frank,” said J. Randall Price, a well-regarded Dallas psychologist who was hired by the defense lawyers to question Marie to develop a psychological portrait of her. (Although Marie would not talk to me, she did give permission for Price to be interviewed.) “Marie might have seen the marriage as a way of taking her mother away. By the same token, Frank was probably jealous of the mother-daughter relationship.”

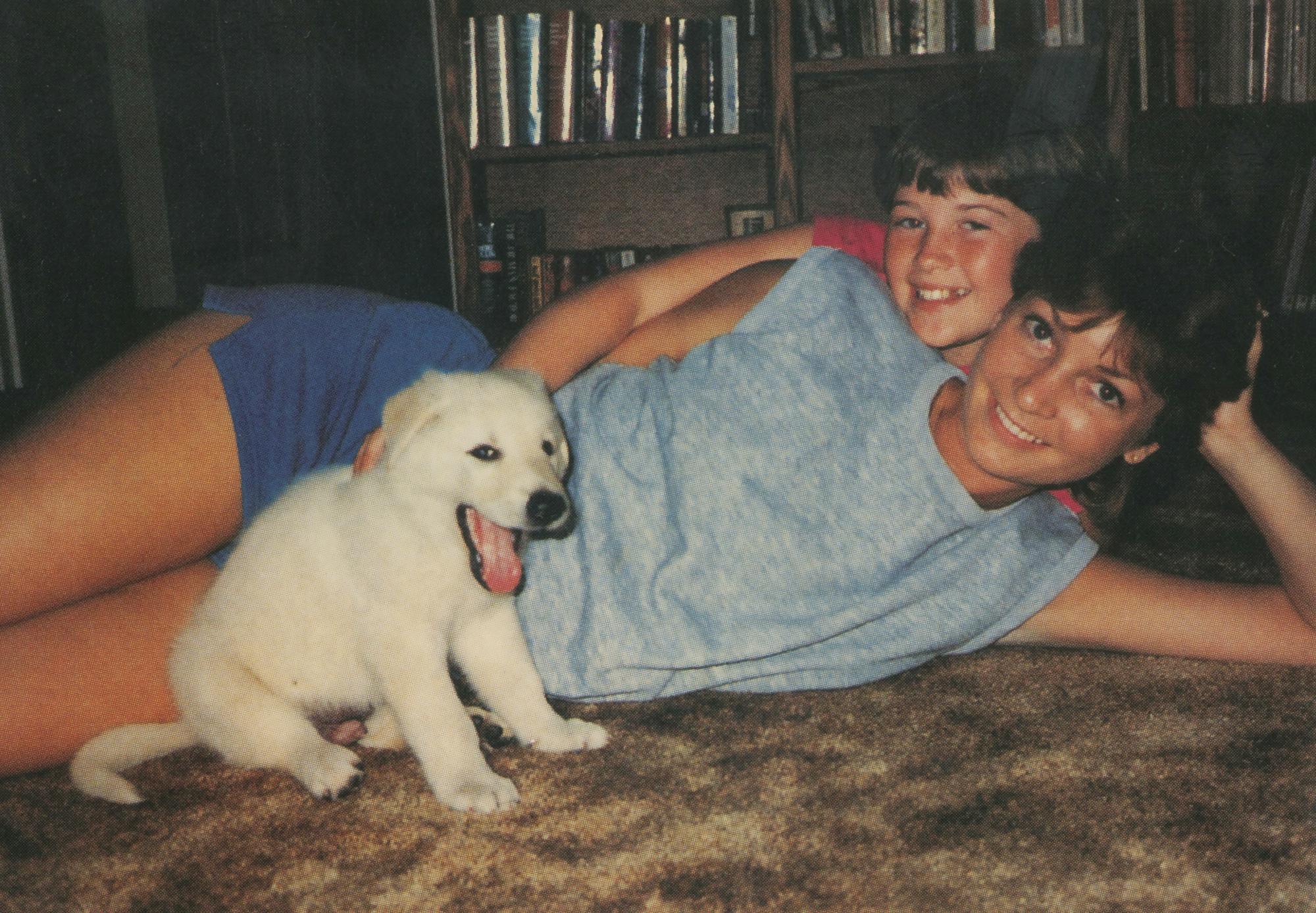

It was obvious to anyone who met Marie and Beth that the two maintained a particularly close relationship. “When I saw them, they were quite affectionate in an overt fashion, hugging one another, finishing each other’s sentences,” said Price. “It wasn’t anything pathological, anything dark or disturbing. But they acted more like contemporaries than mother and daughter. They were like sisters who had grown up together.” When I asked Beth to describe Marie, she used the most glowing terms, telling me that Marie was so intelligent as a little girl that she was already writing words in cursive by the time she reached the first grade. “Marie had strong values in every aspect of her life,” said Beth. “She insisted that she was going to remain a virgin until she got married.”

Although not as extroverted as her mother—she had only a couple of close friends—Marie had a reputation at Granbury High School as a good-natured girl who stayed out of trouble. She played the clarinet in the school band and took art classes and dance lessons in her spare time. But in the summer of 1992, before the start of her junior year, her mother and stepfather nearly split up. “At the time,” Frank Burroughs admitted at Marie’s trial—his only public statement about the matter—“I failed my family as a father and as a husband. I caused grief. Marie had lost respect for me because of what I had done.” What that meant, Beth flatly told me, was that Frank was having an affair—and it was Marie who found out about it. “On the weekend before Marie turned sixteen years old,” Beth said, “she came home and found Frank with another woman.”

Beth was devastated by her daughter’s revelation, but she told Marie that she was going to stay with her husband. “I loved Frank, and I knew that he just didn’t have his head on right,” said Beth. “He felt neglected because of all the time I was spending with my own job [Beth was working in the emergency room at the local hospital], and this was his way of reacting.” Marie, however, couldn’t tolerate her stepfather. She talked back to him. She wouldn’t clean her room when he asked her to. “She withdrew from all of us,” Beth said. “And then one day she came to me and said, ‘I can’t stand being in this house. I think you should divorce him.’ And I said, ‘But, Marie, I love Frank. I know him. I know he’ll change.’ Marie looked at me and said, ‘I have to leave.’”

Beth arranged for Marie to live with Beth’s parents in Fort Worth, where she enrolled in a new high school. But five days later, using all the money she had—about $50—Marie took a cab back to Granbury, 45 minutes away. Frank, however, was a strict disciplinarian, and he had long ago established some rules around the house, one of which was that if Marie or his own son should ever move out to live with another parent, then they couldn’t move back. To him, as he later explained in court, the rule was an important tool for two divorced parents trying to meld two families. He said he didn’t want the kids to think they could go back and forth between parents whenever they wanted to get their way. When Frank’s son, in an earlier period of rebellion, moved out to live with his mother, Frank did not let him return. Likewise, when Marie showed up, he said he would not let her back inside the house.

“It was this terrible scene, all of us outside screaming and crying at one another,” Beth said. “Marie was crying for me to take her back, and Frank was shouting at me, ‘You know the rule, and you can’t break it. The same thing that applied to my son should apply to her.’ He was making sense, I know, but I felt like he was making me choose between him and her.”

In a decision that would come back to haunt her, Beth chose her husband, and she called Steven to take Marie. “I never thought I was pushing Marie away. I thought that her move to Steven’s apartment would only be temporary and that Frank would soon change his mind,” she said. But according to Price, Marie saw her move to Steven’s as abandonment. “She thought that Frank was relieved to have her gone,” Price said. “Marie’s constant presence and her friendship with her mother were hindering him from putting his marriage back together with Beth.”

For his part, Steven Robards was excited about the turn of events. By 1992 medication had largely cured him of his bouts with depression. He had a budding romantic relationship with Sandra Hudgins, a single mother he had met at a Parents Without Partners meeting. Most important, he had found a steady job carrying mail for the U.S. Postal Service. “For Steven, Marie’s coming back to him was like icing on the cake,” recalled his sister, Stephanie Elder. To accommodate Marie, Robards applied for a two-bedroom apartment in his complex.

According to Beth, Marie sent her letters in which she described how she hated her new school, Eastern Hills High School, which was much larger than Granbury High. She also wrote that her father was devoid of most homemaking skills. He had few kitchen utensils. He didn’t clean the apartment. Marie had to sleep in a rollaway bed in the dining room while they waited for a larger apartment to open up. Steven did not frighten or hurt Marie. “He was very anxious about pleasing her, and he did everything he could to make her feel comfortable,” said Sandra Hudgins, who lived in the same apartment complex. “He took Marie out to restaurants and movies. But I know that those first few weeks, Marie was constantly on the phone calling her mother. She was pleading to get back home.”

Beth made no promises to Marie about coming back to Granbury, even when Marie wrote her another letter saying she was suicidal. “I immediately called Marie and told her life was too precious for her to say things like that,” Beth said. “I really thought Marie was only being overdramatic in the way teenagers can be.”

After a few months, it looked like Beth was right. Marie’s grades began improving at Eastern Hills. She was making a 98 in French, a 91 in English, and a 95 in chemistry. “She was in the top two to three percent of my students,” said Tracie Arnold, the school’s chemistry teacher. “I do remember hearing her say that she wanted to move back in with her mother, but she was always a nice, bubbly girl.” Hudgins said that by Christmas, Marie was far more relaxed with her surroundings. “She never talked back to Steven. She was always cooperative. She even asked me if she could help me wrap Christmas presents,” Hudgins said. “In all honesty, she was what you wanted a teenager to be.”

So why, in February 1993, while the teacher wasn’t looking, did Marie pour from a bottle marked with a skull and crossbones and the word “poisonous” in large red letters some barium acetate into a napkin, which she then hid in her knapsack? “It’s one of those mysteries—a teenager’s desperation,” said Price. “For whatever reason, Marie did feel permanently trapped. She told me that prior to the barium incident, she had been thinking that if she could burn down Steven’s apartment when he wasn’t there, she would be able to be reunited with her mother.”

But according to what Marie later told the police, she decided on the night of February 18 to put the barium acetate into his refried beans. After Steven ate his Mexican food, he went to a Wednesday night church service at a nearby Church of Christ. He returned less than an hour later, complaining of a stomachache. He began to vomit. Marie went to Hudgins’ apartment and told her that Steven wasn’t feeling well.

While Marie stayed in Hudgins’ apartment, listening to the radio with Hudgins’ young son, Hudgins rushed over to find Steven in bed, complaining that he was getting stiff in his arms and legs. “He said he couldn’t swallow well,” Hudgins recalled, “and I saw saliva coming up through his mouth. I went into the other room and called an ambulance. While I was on the phone, I heard Steven gurgling. His mouth was foaming. It was terrible. His eyes were open and he was just staring.”

Paramedics tried to get an oxygen tube down his throat to keep him alive, but his throat was completely closed. Marie came back to the apartment and stood in the doorway. “It was like she was in shock,” said Hudgins. “She didn’t tell the paramedics anything. She only stood there.” Finally, Hudgins hugged Marie and pushed Marie’s face into her shoulder so that Marie wouldn’t see her father die. Later that night, Beth and Frank came to the hospital to take Marie home to Granbury.

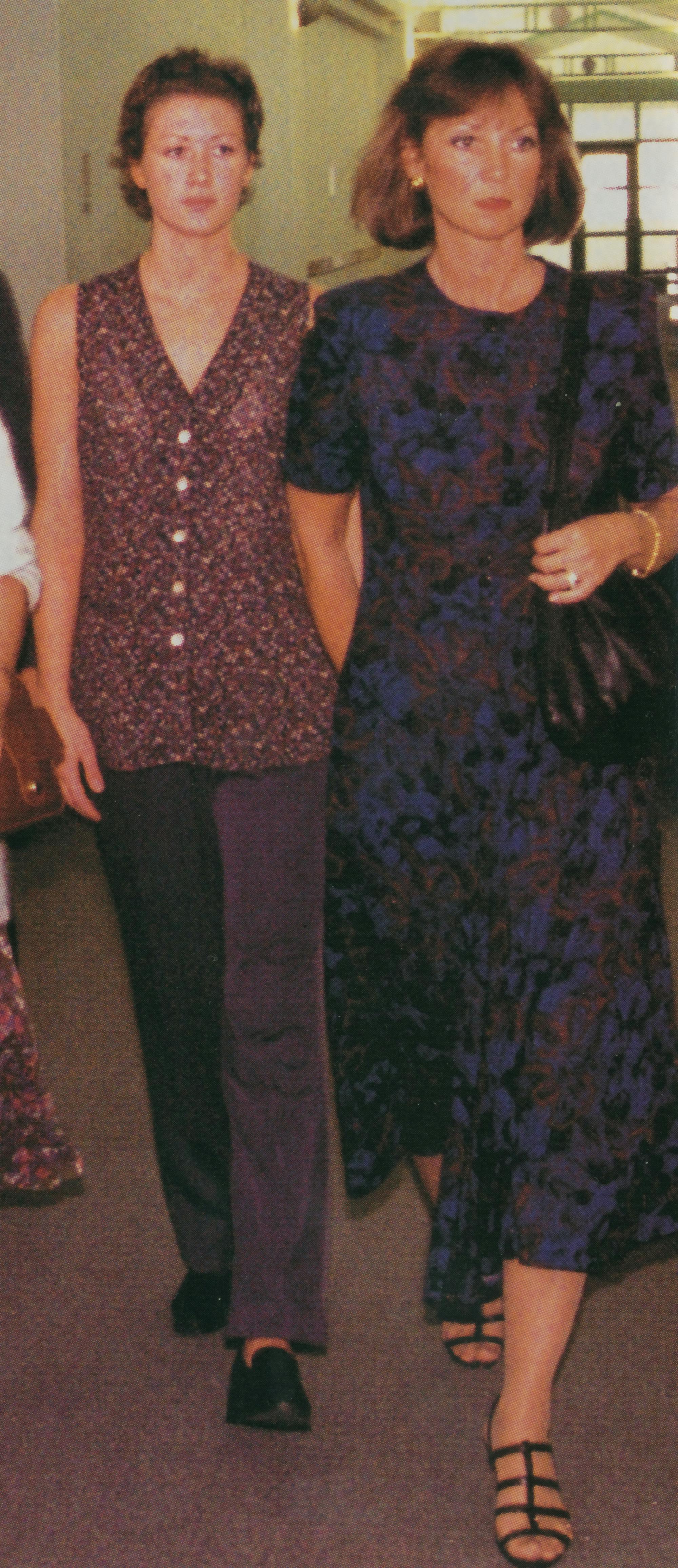

Shortly after Steven’s funeral—during which Marie stood dazed beside the grave—Beth took Marie aside and told her that the two of them were soon moving to Florida. “I told her that Frank and I were still having problems, and so I was moving out,” Beth said. “Marie stared at me. ‘You had this plan all along to take me to Florida?’ she asked. I told her I had found a job there, and we were moving, and we were going to be together again, the two of us. Marie looked like she couldn’t breathe.” Beth paused. “If I had only told Marie one week earlier, none of this would ever have happened.”

Indeed, by the end of March, Marie and Beth were in Panama City, Florida, where Beth had found a job working as an administrative assistant for the state division of motor vehicles. Marie enrolled in the local high school. She was so depressed, however—some days she couldn’t even get out of bed—that Beth was worried that Marie too had become manic depressive. She sent Marie to a counseling center, which did little good. Then, in June, Frank Burroughs arrived in Florida to try to patch things up with Beth.

This time, Beth said, he promised to work harder on their marriage, and Marie was ready to accept him back. But in another almost unbelievable twist to the story, weeks after his arrival Marie found a note in his pillow case from the other woman. Beth recalled, “Marie said to me, ‘Mom, you can put up with him if you want to, but I don’t have to. I miss Texas, and I’m going home.’”

Once again, Beth chose her husband, staying with him in Florida. Marie called Steven’s father, Jim, asking if she could come to Mansfield to live with him and his wife (he too was divorced and remarried). Considering that she could have gone to Beth’s relatives, going to the Robardses seemed to be a bizarre choice. “I think Marie somehow wanted to make up to the Robards family and be the best granddaughter there was,” Beth said. “She was determined to start a new life.”

Robards family members later said that Marie never cracked. “We didn’t suspect a thing,” one told me. “The only thing we thought was a little strange was that she didn’t want to go to Steven’s grave. She told us she couldn’t emotionally handle it.” At Mansfield High School, Marie was known as a straight-A type. She joined the volleyball team and the yearbook staff. “She impressed all the teachers,” said Leonidas Patterson, the yearbook teacher, “because here she was, a brand-new student, and she had this hunger to get involved. When we had our University Interscholastic League competitions, Marie was interested in everything—drama, journalism, and keyboarding.”

Some of the students were mystified by the elegant Marie because she was so reserved and unwilling to talk about her past. Some girls swore that Marie had told them her father was living, and others thought they heard her say he had died. But the always perky Stacey High, who was voted most humorous in her senior class, wondered if the reason Marie came to school perfectly dressed each day was because she was trying to hide some flaw. “I had come from an abused background, and I had been to plenty of psychologists,” Stacey said. “I could tell that Marie had gone through something too. I thought I could help her come out of her shell, teach her to have a little more fun in life.”

Soon, the two fatherless girls were inseparable. (Stacey’s father, whom she almost never saw, lived in Mississippi.) One weekend night, using fake IDs, Stacey took Marie to the country-western bars on the north side of Fort Worth, dressing her in a pair of tight jeans. Patrons at one bar were so taken by Marie’s appearance that they called her the Cowboy Barbie Doll. At school, Marie and Stacey were writing partners on the yearbook staff. Stacey was good at asking the questions; Marie liked doing the writing. “I pride myself on asking really good questions,” Stacey said, “and sometimes when we were driving around town in her Honda, I tried to get Marie to talk about her past and her dad’s death, thinking it might help her. But it was, like, a dead-end street to get her to talk.”

Strangely enough, it was Shakespeare—the writer usually considered so boring by high school students—who got to Marie. If she had been reading her Cliffs Notes on Hamlet, which she had brought along with her the night she was studying with Stacey, Marie would have read that Claudius’ soliloquy in Act III, Scene III showed him to be “an erring human being, not an inhuman monster. Claudius clearly is not a born villain; nor, however much he has sought to conceal his real self from others, does he seek to avoid moral and religious truth. . . . At this particular moment in the action, it is possible to feel some pity for this tormented man despite his appalling crimes.”

After her confession, Marie begged Stacey to tell no one. “You’re the only person who knows,” she said. But that night, Stacey went home and told her mother, Libby High, who was as close to Stacey as Beth was to Marie. Libby, who worked in nursing education, initially thought that Marie, overcome with grief about her father, had made up the story. But when Libby called the poison center number to ask if barium acetate could kill a person by closing his throat, the person on the line said it certainly could and then asked suspiciously why Libby wanted to know.

Incredibly, Libby did not call the police. She told me that after her disastrous marriage, she felt an added responsibility as a single parent to prepare her daughter for the rigors of the real world. “I wanted Stacey to know that I trusted her to make her own decision about Marie,” Libby said. “I guess I knew that this was the moment in which Stacey was going to have to grow up.”

Instead, as Stacey agonized Hamlet-like over what she should do, she came close to what she said was “a complete mental breakdown.” She spoke several times about Marie with a high school counselor, never mentioning Marie by name but referring to her as a friend of a friend. She confided in a few friends who had already graduated from high school what Marie had told her. “They said, ‘Stacey, quit lying, you need a reality check, girl,’” Stacey told me. She had nightmares that Marie was chasing her through a forest. “I could hear Marie breathing real slowly, just like it was a horror movie,” Stacey said. “And then I’d come to school the next day and there she was, this very nice person. We’d sit and talk in this little office in the back of the yearbook class, and I would tell myself that Marie had only made a teenage mistake. I kept saying, ‘Marie, I really think you need some counseling.’” At her mother’s suggestion, Stacey lied to Marie, telling her she had confessed to a priest about Marie’s secret. “Maybe I overreacted,” Libby said later, “but I thought if Marie ever wanted to harm Stacey, she wouldn’t do it because she believed Stacey had told a priest.”

In February 1994, on the anniversary of Steven’s death, Marie’s grandfather took Marie and Stacey to the Macaroni Grill for dinner. Jim Robards tried to make a couple of toasts to Steven, but Marie wouldn’t listen. “I asked her if she wanted to put flowers on her daddy’s grave,” Stacey said, “but she said to me she didn’t even know where his grave site was. She told me she was over her father’s death and didn’t want to think about it.” Like Claudius, Marie could not repent.

A few weeks later, after having more nightmares, in which she heard Marie’s father calling to her from the grave to save him, Stacey went to her high school counselor’s office and asked the counselor to call the police about Steven’s death.

The investigation should have been simple enough. All the medical examiner’s office needed to do was retest Steven’s blood. (The office keeps blood samples from autopsies it has conducted.) A deputy chief examiner, however, later said that it took almost three months to find a laboratory with a machine that could run a test to check for barium acetate, and then another few months passed before the test results were sent back. A possible explanation was that the overworked Fort Worth homicide unit had more important things to do than investigate a preposterous-sounding story from an overwrought teenager about her best friend poisoning her father.

The longer the police took, the more Stacey second-guessed her decision. She and Marie never spoke about Steven’s death again. Eventually, Stacey dropped out of the yearbook class so she wouldn’t have to see Marie every day. She began missing school, staying out late, and as she put it, partying too much. In April Stacey checked in to an after-school program at a private psychiatric treatment center in Mansfield. “I walked in and told them my life was swirling down the toilet.” But at the prom, she did pose with Marie for a photograph. “She was so beautiful that night,” said Stacey, “that I couldn’t believe she had ever done anything wrong. I kept thinking, ‘Maybe we can all just forget this ever happened.’”

After graduation, Stacey went to Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, about a three-hour drive from the University of Texas at Austin, where Marie was. The two never spoke, and Stacey tried to concentrate on her education. But late one night in October, a detective called to tell her that he would be arriving the next morning to take her statement. The tests had shown that Steven Robards had 250 times the amount of barium acetate normally found in a person’s blood. Stacey was so panicked that she got out of bed, went to her dorm’s vending machine, and ate five Snickers bars.

Marie was let out on bond, and she went back to Granbury, where her mother and Frank, still together, had moved earlier that year. (Frank had been offered a job as a deputy sheriff for Hood County, and Beth worked as a clerk for the city.) While waiting for her trial, Marie got a job as a waitress at a TGI Friday’s in Fort Worth. A film director hired to shoot a Friday’s commercial was so impressed with Marie that he used her in a scene serving drinks to customers. “What’s so tragic is that total strangers could meet Marie and see something special in her,” said Beth, breaking into tears. “She felt trapped, and I let her feel that way. I didn’t give her any hope.”

Using the life insurance money that Marie had received after Steven’s death—more than $60,000—Beth hired two veteran Fort Worth defense attorneys, Bill Magnussen and Ward Casey, whose strategy was to convince the jury that Marie didn’t know that barium acetate could kill a person. If the jury believed that she had not intended to kill, then Marie had the chance of receiving a lighter sentence for manslaughter rather than murder. “She only wanted to make her daddy sick overnight,” Casey told the jury in his old-fashioned oratorical style. “She only wanted to go home to Mama.”

Each day of the trial, the courtroom was packed. (One high school civics teacher thought it would be educational for his class to sit through testimony. The students listened for a while and then began to write notes. One girl sitting beside me wrote her boyfriend a letter that began, “I am psycho in my love for you! Do you hear my heart pounding.”) Spectators craned their necks to get a look at Marie, who by then was nineteen years old. She had cut her hair in a short nunlike bob and wore sleeveless, flower-print blouses and loose-fitting pants. Throughout much of the testimony, she put her right hand on her cheek and sobbed silently. During breaks, her mother, who could not watch the proceedings because she was a potential witness, came into the courtroom and wrapped Marie in her arms. Frank sat outside on a bench, speaking to no one. Members of the Robards family sat stone-faced on the right side of the courtroom.

One of the more emotional moments in the trial came when Jim Robards took the stand and said that as upset as he was over the death of his son, Marie should be forgiven and offered a probationary sentence. Randall Price arrived to testify that Marie was not deranged but was so consumed with remorse over Steven’s death that she was experiencing a version of posttraumatic stress syndrome, unable to express her emotions. Price was also going to say that he believed Marie never wanted her father to die, but the defense attorneys, for reasons that remain unclear, did not call Price to the stand, which gave the prosecution an unhindered opportunity to rip into Marie, telling the jury that she cavalierly poisoned her father and never tried to help save him when the paramedics arrived.

The prosecution’s most important witness, of course, was Stacey High. Wearing a green dress, brown loafers, and white socks, she came to the stand, nervously sucking on a breath mint, and said that Marie had told her during one of their conversations that she knew the barium acetate would be fatal. At one point, Stacey turned and looked at Marie. They locked eyes, then Marie dropped her head.

In the end, the jury was apparently swayed by prosecutor Mitch Poe when he said in his final argument, “Just one stomachache wasn’t going to get Marie back to her mama’s place . . . Steve Robards had to die.” The jurors convicted Marie of murder, which left them with the question of deciding her sentence. The defense attorneys felt they had no choice but to have Marie testify.

She nearly stumbled as she walked to the stand. In a squeaky, trembling voice, she told the jury she had never been convicted of a crime. She said that her only contact with the Robards family since her arrest was a birthday card she had sent her grandfather.

Then Casey asked, “Marie, did you love your dad?”

“Very much,” she said.

“Are you sorry you killed your dad?”

It was time for her to repent. Bursting into tears, she turned to the side of the courtroom where the Robardses were sitting and said, “I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.”

Poe said Marie deserved a life sentence because she gave her father a death sentence. The defense attorneys begged for probation for a girl they said would have to live with the guilt of her father’s death for the rest of her life. The jury split the difference, giving Marie a 28-year sentence—she will have to spend at least seven years in state prison before being eligible for parole. (Claiming that the prosecution used improper testimony about Marie’s state of mind during the trial, her attorneys have filed a motion for a new trial. If that fails, they will appeal the verdict.) Outside, in the courthouse hallway, Poe told the local press that Marie was a “teenage narcissist.” Surrounded by television cameras, Stacey High dramatically said, “I’m ready to wrap up this phase of my life, hopefully major in neuropsychology in college, and be a wonderful citizen of the United States.” Beth and Frank were the last ones to leave the courtroom. For nearly an hour after the sentencing, they sat alone on the front row, holding hands. “Frank and I have made our mistakes,” Beth later told me, “but we’re going to be strong together. We’ve got to go on. Our marriage will survive this.”

For several days Marie remained on a suicide watch at the county jail. But a week after the verdict, Price went to see her. “Marie asked me if she could get her college degree while she was in prison. She told me she was anxious to start some kind of schooling, to improve herself, to accept her punishment and move on,” Price said. “She was wearing these paper clothes, which the jailers give prisoners on a suicide watch, and she was shivering in her cold jail cell. But she told me she had no right to complain about her own problems because she had already caused so much suffering. It was sort of amazing to listen to her.”

From jail, Marie also called her mother collect every night. In one of those phone calls, she told Beth that she hoped Stacey didn’t feel badly about going to the police. She still liked her, Marie said. After all, she added, the two of them had once been best friends.

- More About:

- Longreads

- High School

- Crime

- Fort Worth