This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

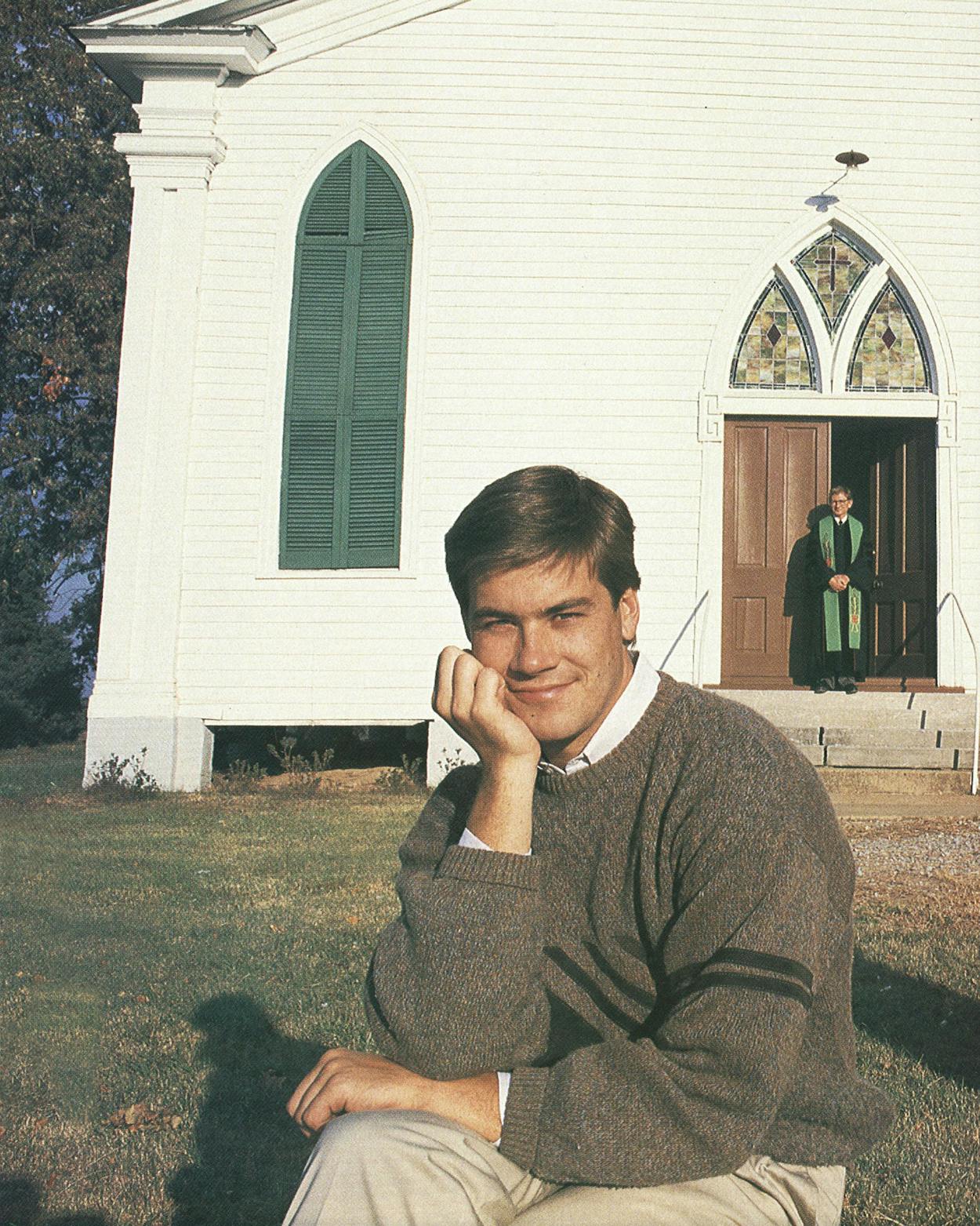

Since most of the men in my family have been Presbyterian ministers—my father, my two uncles, and my grandfather—it was assumed that I would follow along and continue the tradition. Which is why it was a bit of a shock to the family when my little sister announced that she would be going to seminary. I was in Dallas doing what I often had explained was “the Lord’s secular work.”

“Well, it happened,” said my mother, whose devotion to the ministerial life was so strong that right after she graduated from college she moved to a women’s Christian education school across the street from a Presbyterian seminary for the sole purpose of meeting and marrying a young minister. “I can’t say I thought it would happen this way, but it seems we have another minister in the family.”

I wanted to apologize for its not being me. But since I had dedicated most of the Sunday worship services during my adolescence to the feverish diagramming of football plays on the church bulletin, it was obvious that the burden of faith seemed more suited to my little sister, Laura, whose favorite childhood game had been draping the living room curtains over the chairs and pretending that she was a missionary in Africa, gingerly setting out bowls of Cheerios for the starving.

Of course, it is a wonder that preachers’ kids ever consider the ministry in the first place. Every day while growing up we watched the quest of common men trying to deal with uncommon passions. Through our front door came drunkards, adulterers, men who had done time, bigots, gossips, and deacons so self-righteous that my father would hide in the closet and make me tell them that he was not home. Couples arrived at the doorstep to talk about their crumbling marriages. Garden committee members marched in to lambast the quality of the flowers in the sanctuary. There were worried phone calls about devil worship, abortion, and the theological propriety of putting peace signs on the walls of the church. And we witnessed our share of church scandals, from the man accused of stealing money from the offering plate to the bridegroom who, at one of the first weddings my father ever performed, stole my father’s checkbook, forged $1000 worth of checks, and took his wife on an extended Florida honeymoon. As a minister’s children, we could not help but be fascinated yet repelled by church ways.

Last summer I went to Houston to hear my little sister preach her first sermon before the congregation of Memorial Drive Presbyterian Church, where she was working as a seminary student intern. Although I was unsure why she had decided to follow the legacy of her father and grandfather, I realized in a vague way that it was inevitable that one of us would. Ministers’ children, more than anyone else, understand one of the most practiced rituals of life—churchgoing. From birth they have been part of a comic and sorrowful, always indomitable struggle of people who want to be holy but don’t have the slightest idea how to go about it. Going to church remains the chief way for everyday citizens to try to grasp a few truths among the tantalizingly undefined questions that surround their lives.

It wasn’t as if our lives as preacher’s kids allowed us to rise above the petty ways of the world. The opposite was probably closer to the truth. A minister’s child faced unusual difficulties in sentimentalizing the gospel, especially having seen his weary father return from a meeting in which the debate focused on the best way to kill pigeons that had been defecating in the church gutters. We three children told each other Jesus jokes (“What did Jesus say up on the cross?” “I can see my house from here”), and our round-the-table prayers after the evening meal grew into fierce competitions to come up with the best line, typically climaxing with one of us asking for the elimination of all disease by sunup. The church was just an everyday part of our lives. We lived next door to it, used its wall as the home-run fence for our softball games, and sneaked inside at night to play scary music on the organ. Our lives were molded by the peculiar contradictions that emerge only from the subject of religion. While Dad in the living room talked quietly to a dying old man who wanted to make a last-ditch effort to stay out of hell, we children would be giggling in the kitchen as we assembled decoupages of the Baby Jesus under our mother’s watchful eye.

For preachers’ children attendance is mandatory at every event of the church experience. There was no question that we would go to Sunday school, the eleven o’clock morning worship service, and then the evening youth group. We went to church camp. We starred in the Christmas Nativity scene. We were at Bible studies and Young Life meetings. We sat through those interminable senior high rap sessions, in which over the course of one evening we would give our opinions on nuclear war, poverty, the moral consequences of touching a girl’s breasts, and the salvation of pygmies in Africa.

It is surprising how the childhood church experience—even for those people who now refuse to go and who find church as cheerless and insistent as a headache—has stayed darkly alive, like a creature under a stone. I cannot recall the number of times that I have heard people say that as soon as they have children, they will return to church—not for themselves but for the children. Though they feel the chill of disbelief today, they remember church as a place of innocence where they learned many of their first lessons in life.

In most adult conversations regarding the problems with religion the topics range from such weighty issues as an omniscient God who can allow pointless suffering to the enormous leap of the imagination required to believe a dead man can literally get up and walk out of a tomb. Ministers’ children, however, instinctively know that the real problems began long before. They began with youth choir.

I have long argued that the reason most people left the church vowing never to return was that their parents made them sing in youth choir. To this day, out of the mouths of grown men and women one hears the phrase “It was worse than youth choir.” Sunday school, certainly, had its moments; that comatose, unblinking stare that seems born into all children probably had its actual origin in the Sunday school room, where a teacher, blabbing away like a salesman trying to unload vacuum cleaners, first explained the theory that God is Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

But there was nothing like those Sunday afternoons when distraught children had to rehearse such awkward songs as “Kum Ba Yah” and “Joy in My Heart.” Although my two sisters and I spent most of our childhood in Wichita Falls plotting terrorist strategies against one another, we were always united in our revulsion to choir. Once a month the choir would perform at the morning service, standing before the congregation in our ridiculous white robes—complete with big red bows—that came just below our waists. Our choir director, a woman who resembled one of those fairy-tale characters that went about driving stakes into people’s heads, would exhort us to “let the beautiful voice of Jesus speak through your music,” and off we would go, our voices wobbling like the call of a basset hound, staggering under ponderous lyrics, like “There is a fountain filled with blood/Drawn from Immanuel’s veins.” It seems safe to say that after such performances Jesus wept.

My greatest moment of rebellion against the institutional church was when I announced that I would no longer be in the youth choir. I remember using a metaphor about wild horses dragging me into the choir room. My mother’s eyes gently examined my face then lowered as she placed her hands together. “Well, of course, we’re not forcing you to go,” she said. “But have you ever thought what the church would be like without music? What would we do without hymns? And what if there was no one to sing them?” I had known that she would say exactly that, and I had my response ready, but just then my father walked in and said that I sure as hell was going to stay in the choir, because if I quit, all the other boys would quit, which meant the choir director would get upset and spend the afternoon crying in his office, and he didn’t have time to worry about that right then.

Preachers’ kids rarely rebelled, despite the old theory that they were the wildest people in school. The reason we never did anything is that we knew we would never get away with it. Women who belonged to our church regularly called my mother when they decided that I was driving the family station wagon too fast down their street. A kindhearted woman informed me that the best example I could make as a minister’s child was to carry my Bible to school and read it during study hall. The only time I drank beer in high school was at a weekend swim party for the cast of the senior play. By the time I returned to school the story was spreading that I had drunkenly thrown up in the shallow end. A couple of my friends from church stopped by my locker to say that they were praying for me—a sure indication that it was only a matter of days before my parents found out.

My father understood the plight of the minister’s child all too well. His father, who was a well-known Presbyterian minister from Virginia, would not allow him to say that he was going outside to play with his cars because it sounded as if he was going outside to play cards. Things loosened up somewhat by the time we were born, but my father made us follow certain rules, the most obvious being that we would go to church and the most troublesome being our use of the English language. We children spent many dinner conversations asking again for his explanation of the proprieties of the word “damn.” He could use it, for instance, when he referred to souls of church members or when he spilled coffee down his shirt.

We never could figure him out. He seemed to be much more understanding when my older sister confessed doubt about the Virgin birth than when he learned that I had been caught at the neighborhood drugstore stealing adhesive tape for wrapping my wrists at peewee football practice. It so enraged him that he preached a youth-day sermon on the horrors of little boys who steal. Yet he hardly said a word that fateful summer when I neglected to put oil in the church’s riding lawn mower and burned up the engine. Although the lawn mower had led me into numerous scrapes before (once I plowed into the garden committee’s prize rosebush), I was sure the episode had ruined me. Several members of the board of deacons angrily demanded that I come up with the $500 to buy another lawn mower. But my father, to the astonishment of even my mother, defended me from those beastly men, let me keep my job, and did not make me pay for the new machine. A few weeks later someone told him I had said “shit” in the church hallway before the morning service, and he nearly blistered my butt.

Ministers have a ridiculously complicated life. After spending all day counseling church members about personal problems (“Reverend Hollandsworth, dadgummit, I think I’m having a lover’s quarrel with the Lord”), they must return to their families, who are not the ideal group in which to confide. My father would come dragging in to the dinner table, worried about declining membership or a church budget that needed to be slashed, only to have his thoughts interrupted by his youngest daughter, who wanted to know how a snake could hand Eve an apple if a snake had no hands. Nor could he relax for a second, because he knew his children would relentlessly hunt down his mistakes. A low moment, no doubt, for our father was the day he pulled into the driveway and ran over our cat. All three of us children came screaming out the back door to look at Mitzi dead on the concrete. Dad was so upset that he stormed speechless into the house. We followed him inside, our faces wet with tears, yelling such things as “How dare you call yourself a minister when you don’t show any feelings for our cat?” This man, who has made his living —and shall make his dying—on the preaching of the gospel, stared at us for a minute, utterly trapped, then blurted out, “I’m sorry! I didn’t do it on purpose. What do you want me to do? Raise Mitzi from the dead?”

I have tried many times to get my father to explain his feelings when he would look down from the pulpit in the middle of the eleven o’clock service to see his children ignoring him for the loftier pursuits of pinching one another, carrying on hymnbook races (the first to find a certain page of the hymnbook won), shooting rubber bands, and trying to spill the Communion plate onto our laps so that we would have little bread wafers to eat during the sermon. “All I can tell you,” he said once, “is that I literally had to control myself to keep from walking down there and beating you to a pulp.” My mother, perhaps the kindest woman I will ever know, would become so angry at me during the service that she would write notes on the back of the bulletin regarding the number of times I was going to be spanked when we got home.

But the greatest worries for our parents were not from the typical situations that result in parental nervous breakdowns—marijuana in the closet, birth control pills in the closet, unfamiliar naked girl in the closet. My parents, I suspect, would have preferred a normal emergency, such as their daughter drinking all the booze at the home where she baby-sat, to having to cope with the sight of their only son standing out in the back yard, trying to speak in tongues. They were always a little bit afraid that one of us would run off and join a cult.

We children never went through much disbelief; instead, our lives were punctuated by excessively devout moments. Laura spent much of her childhood drawing up plans to open a Christian orphanage. My older sister, Cathy, became an active member of a liturgical dance group, which tried to bring a fresh spirit to church services. The group created something of a scandal one Sunday at the call to worship when the girls began dancing in the sanctuary, their breasts bouncing under the thin fabric of their leotards like beach balls. During my most pious period (the high point of which occurred when I heard the voice of God speaking to me through the bonfire on the final night of a high school church camp), I was led to write on the wall above the urinals in all the men’s rest rooms I could find, “Repent and be saved,” hoping that generations of men would be able to look up and see the light. At the annual national Presbyterian meeting the year I went as a youth delegate I embarrassed the entire Hollandsworth family by standing up in the huge convention hall and before all the leaders of the church declaring that Presbyterians should end their opposition to gambling because it made them appear out of touch with the real world.

As we grew older and went off to college and into adult lives, we lost the cohesion we had had as a minister’s family. We also lost the impulse to be a part of every Christian phenomenon that came down the pike. A lot changed. Most of our childhood friends were no longer attending church. Sunday dinner wasn’t as important as it once was. The Sunday blue laws were on the verge of repeal.

But a couple of years ago, mostly through snippets of phone conversations with our mother, Cathy and I began to hear that Laura, who was then a senior in college, was going on to seminary. We couldn’t believe it. “I can’t either,” said Mother. “I think it’s because she doesn’t know what else she wants to do.”

There was no question that she had been the most spiritual of the three of us, yet her decision was so unexpected that we could only laugh. Our father reminded us what we had been taught from our first days in Sunday school, that the way our religion works is that the people who carry on the message are those you least foresee. I also remembered another story. While staying in the church nursery during a service, two-year-old Laura heard her father’s voice emanating from the sanctuary. Trailing the voice, she walked out of the nursery, down the hall, into the sanctuary, and stopped in front of the pulpit with her arms open. It was natural. For most of her life Laura had been called to stand in that pulpit.

And so I went to Houston to hear her preach. We had stayed somewhat in touch through her first year in seminary. She told me seminary students spent a lot of their time discussing the Virgin birth, homosexual ordination, whether ministers should feel obligated to recite a prayer before every meal they eat, and the advantages of saying God the Mother along with God the Father. She was involved in the same arguments we had had at the family dinner table. Most seminary conversations boiled down to quoting the right theologian at the right moment. She also sensed that she was spending too much time learning Greek and Hebrew when after years of observing the dynamics that brought out our father’s most ignoble profanities, she thought it might be more helpful to take a course on how to politely hang up on church members who call to demand that the church kick out teenagers who show up for services in blue jeans.

Laura went to the Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia (the same one our father, uncles, and grandfather went to) “just to see what it was like for a year.” She wasn’t sure she would stay. She would lie awake in her bed through the night, wondering whether she was fit to be a minister. She realized that she was searching for something that she would never fully understand until she reached it, if she could even do that. About halfway through her first semester she decided that despite her uncertainty she had never felt so comfortable with herself or so challenged. She remained.

As the seminary intern at Memorial Drive Presbyterian, one of the largest Presbyterian churches in the country, Laura had a little office, where she regularly talked to college students about drugs, sex, alcohol, and the meaning of the Resurrection. I could see her doing that. She could sit for hours through the most meaningless chitchat and never be bored. She had a tendency, however, to get so involved in other people’s lives that she would become overwrought and unable to think of anything to say. At the last big Hollandsworth gathering—my older sister’s wedding—the family spent hours preparing rehearsal dinner speeches. One by one we stood up, cheerfully recalling every terrible thing the eldest child had done, until it was Laura’s turn. She slowly rose from her chair, took one look at her sister, realized at that moment all that marriage represented, and burst into tears. Every one of us in the family wondered how in the world she was going to get through a sermon.

We found out at the early Communion service. I sat with Cathy, who is a doctor in Houston. It had been a long time since we had been together in church; to keep peace in the earlier days our mother used to make us sit six inches apart and prohibited us from crossing an imaginary boundary line. We looked around. Since it was the eight o’clock service, only a few dozen church members had come. Even though we had never been to that church before, we felt as if we knew them—a myriad of individuals who tried regularly not to sin but felt regularly sinned against, who knew they must love their enemies yet hardly felt able to love their friends. We had seen our father Sunday after Sunday attempt to ignite the unenthusiastic minds before him. As soon as he finished and stood by the front door to shake hands, he was already thinking about the next week, aware that their questions would still be there—people making private bargains with their intellects about what to believe and wondering whether there was any grace after their own failures of hope and courage.

Now Laura was ready to take her place and act out her role—one more voice among the countless others trying to explain that there is good amidst the greed and cruelty. Her eyes blinking quickly behind her glasses, she approached the pulpit, the chancel behind her forming a large, shining backdrop. Her thin little smile was scarcely visible. As often as I have been able to second-guess what my little sister was up to, this time I had no idea what she was thinking or what she would do.

Her face strained with effort, and she began to speak. She talked about the sacrament of Communion, the ritual of taking a bit of bread and a sip of wine that is symbolic of the Last Supper. She called it, appropriately, a family meal. Her voice suddenly grew stronger, filling with authority. “We who are many are one body,” she said, “for we all partake of the one bread.” With a burst of exuberance she threw her right arm out wide as she proclaimed, “We are called upon to open our lives to the needy—whether someone is needy in body, mind, or soul. It means we open ourselves completely to the will of God, as did Jesus Christ. It means we are willing to suffer and die for Jesus’ sake.”

My older sister and I looked at each other. Laura was using the same gestures, the same nod of the head, the same inflection of sentences that our father used. She even gripped the podium the same way. The tradition continued.

It seemed ironic that my little sister would be roaring like a young lion in the church just as my father was beginning to admit that his old, firm sermon voice had grown a little quieter. All of us have noticed that with age he has become more aware of the mystery that lies at the heart of his faith, of the confusion caused by a God who can be seen only through a glass darkly. Older ministers, after a lifetime in the church, seem much more accepting of a God who is sometimes absent, who is called to by human beings as much out of anger as of love. They recognize that the brash dogmatic preaching of their early years has given way to a theology that understands how grace flickers obscurely in the shadows. The last time I heard my father preach he gave a brutally honest sermon, speaking of his own need for spiritual renewal. “I confess,” he said, “that the energizing source of God’s daily presence, the wind of the Spirit, has abated somewhat.”

My father has never been the kind of minister who made his money in this world by talking a lot about the next. He is just another pastor, heading off to a hospital late at night to sit with an old lady who’s dying alone, constantly facing challenges by glib college students to prove the existence of God, trying to tell a man whose wife has left him that Christianity is not merely a subject of metaphysical speculation, weeping in the pulpit during a Sunday service two days before Christmas because one of his church members had been killed in a car wreck. He once had to deal with a woman who walked into the bathroom while he was taking a shower because she wanted to discuss problems with the church furnace. He also had to pick up two boys from an elementary school to break the news that their father had committed suicide. He illegally drove a church member who was on probation and wanted by the police across the county line so the man could see his wife and new baby; the man hid in the backseat of the car. My father said he did the act “out of a misguided sense of compassion,” but one of my father’s strengths is that his compassion does not have limits.

My father can look back upon the fragments of his life and all the moments of indecision and muffled understanding, and he can still say he has never been alone. Some of us have trouble comprehending that. But he says that he has been a part of a great legacy, one beyond his comprehension, one that has never let him go. His father had to be led from the pulpit in the middle of a sermon because his voice faltered and no more words would come. My grandmother ran down the aisle to grab his arm. He was 64 years old and having a stroke. It was the last sermon he would ever preach. A few years later he died.

Laura once found an old tape recording at her seminary of our grandfather preaching a sermon. She brought it home, and we put it on the tape recorder and watched the tears well up in my father’s eyes. Back in the kitchen, my mother, a woman of such simple, firm faith, the one who taught us all the Bible stories and made us play Bible memory games on family vacations, was alone at the table, reading from her old red Bible, searching for the right verse to deliver to her Sunday school class. Even though I was not the one to carry on the legacy, I could not help but be moved by those scenes.

As Laura approached the end of her sermon, she glanced out at her brother and sister. Her eyes were looking so persuasively into mine that I nearly glanced away. Here was the little girl who used to dance in her nightgown and bare feet to the hymns her older sister played on the piano. Here was the little girl who took all her dolls out on the grass and laid them on their backs so they could look up and see heaven. Here was the girl who had played the role of Mary at the church’s outdoor Nativity scene and had looked down at the Baby Jesus with such devotion and tenderness that she was not aware that the three Wise Men (one played by her brother) were snickering as they offered gifts they had found down in the church’s Boy Scout room—a snakeskin, a crow feather, and a rusty old fishing knife.

Laura finished her sermon and sat down. She had not stumbled once. I put my fingers to my nose and wiggled them at her as I used to do when we were kids. Laura looked back and rolled her eyes. Watching her fanning her flushed face with her sermon notes, I realized that the faith our parents had tried to teach us from birth, the faith that had often seemed so absurd, would always be there.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Wichita Falls