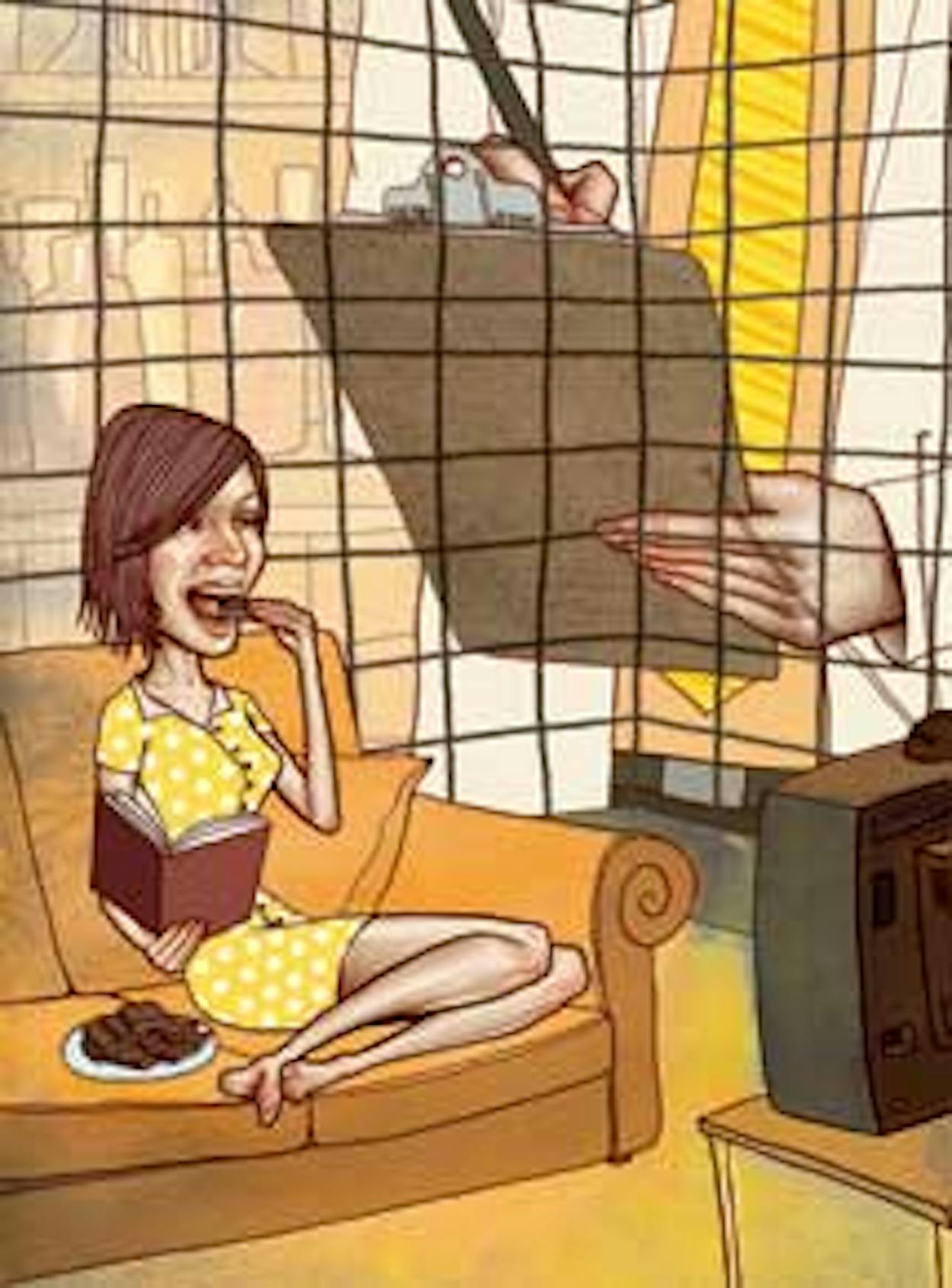

Like so many people, I love the fact that Robert Rodriguez financed his earliest films by offering himself up as a human lab rat for drug studies. I had the same dream. Not the filmmaking part—the drug study part. A few months ago, I began sending feelers out into the world of the clinical trial. I saw myself in a climate-controlled high-rise, hooked into premium cable, every meal premeasured and served on a red plastic tray, part of a jolly crew who gave one another nicknames and promised to stay in touch even after the IV lines were removed. I would have with me a tall stack of all the books I’d ever pretended to have already read: Russian novels where the characters have versions of the same name; English novels where one class oppresses another yet both are equally miserable (though some get to do their suffering in jodhpurs and ascots while others have to weave their clothing out of peat). I’d devote my first day to a serious run at Middlemarch, then spend the rest of my stay playing Scrabble online and rewatching every episode of Weeds, 30 Rock, and Project Runway.

Best of all, my mother would invite the whole gang to make fudge together in the facility’s austere, industrial kitchen, which is what she did when she helped run drug studies back at the University of New Mexico (go Lobos!) in the early seventies. She worked as a nurse at the student health center, whose infirmary filled up every other weekend with very small children who were among the first to use growth hormones. She prepared for their arrival as if she were hosting the most fun sleepover ever. She packed up our long-abandoned Chutes and Ladders and Candy Land games, along with magical coloring books that required only a splash of water to make the predetermined hues appear and bags of all the best sugars (white, brown, powdered). I thought often of these wee folk eating the taffy and divinity that she should have been whipping up for us, her own six children. “Drug study” came to be code for “enchanted tea party in the woods with fairies and elves.”

I wanted in. I had my own growth issues. After hitting five feet ten by my eleventh birthday, I’d gone to the library and read about a procedure developed in Sweden that involved slicing several inches from the thighbones of girls—always girls—who wanted to be shorter. Hard to imagine a time when this seemed like a good idea, before the WNBA and beach volleyball alerted the world to the glories of the elongated female form. Once I accepted that I was about a foot and a half too tall to party with the little people, I gave no further thought to drug studies for the next few decades. Maybe it was this summer’s hellish heat that reawakened dreams of life as a guinea pig in a cryogenically cooled lab.

The screener at the first study I applied for (“Test With the Best!”) told me I didn’t qualify: I was too young. I was told the same thing the second and third times I called. The fourth time I was asked never to call again. The paid-vacation-type studies that I inquired about wanted only Christian Scientists, since prior use of almost any drug meant automatic elimination. Then I hit the mother lode: a dermatology research lab looking for subjects to test a skin cream that might reverse sun damage. Eureka! My forehead was like something out of Babylon 5.

The lab was located in a complex that housed enterprises like ProLogistix, which was either a company that sold gym equipment or a CIA front. When I finally found Warts ’n’ Such (not its actual name), I immediately saw how great medicine could be when funded by Big Pharma. First of all, no sick people. Second of all, no waiting. Before I even had a chance to pick up a copy of Derm: The Reckoning! I was escorted back to an examination room.

After an even briefer wait, Dr. Acne Scrub (not his actual name) entered. A kindly retiree from West Texas with a gracious, courtly manner, he wore a lab coat with a patch on it that identified him as a member of the American Academy of Dermatology. That gave me confidence. (Though, when you think about it, aren’t doctors overdue for a rebranding? True, nothing said “quality medical care” to the ancient Greeks like a snake wrapped around a rod, but haven’t we moved on? Couldn’t we jump forward an entire millennium simply by making the snake a leech?)

Dr. Scrub touched my forehead gently, peering at the florid mottling thereon through a pair of magnifying specs cantilevered onto his actual glasses so that they extended out like crab eyes. I was thrilled when he pronounced my skin catastrophic enough to qualify for the study, because, as he began describing the cream that would be tested on me, I recognized it as the sort of cosmetic miracle I could never have afforded. Redness, stinging, burning, peeling: I would be shedding the entire Babylon 5 cocoon and releasing the petal-soft butterfly within. I was as hopeful as I’d been while reading about that Swedish petitification process.

Dr. Scrub sent me off with a bag of test-cream sachets, instructing me sternly to apply it only at night. I promised to honor the other pioneers of science who’d gone before me . . . then rushed out, tore into the first packet, spread it on, and waited for the caustic bite of whatever Frankenstein cocktail of glycolic acid and paint thinner was going to turn back the liver-spotted hands of time.

Nothing. Not the tiniest tingle. I was that bridesmaid of the clinical trial, the control group. My spirits drooped as I walked into the sun, which would now continue to have its way with me forever. Thinking of how I would rub in the placebo cream every night knowing that absolutely nothing would happen, I wondered for the first time if any of the tiny kids had been given worthless sugar pills. That saddened me, but at least they’d gotten some of the real stuff. At least they’d made fudge with Nurse Bird.