Early one Wednesday evening in February 1988, a sophomore at Austin’s Westlake High School named Mike Smith called his mom and asked for a ride home. He was sixteen, blue-eyed and blond-headed, tall and slightly built, quiet but known by the kids as a nice guy, a good student, and a middle-of-the-pack finisher for the school’s JV cross-country team. It was shortly after five o’clock. Track practice had just ended, and he couldn’t find the friend who normally gave him a lift.

His mom, Sherry Taylor, was an office manager for a plastic surgeon, and she wasn’t quite finished at work. The previous couple of weeks had been rough: she’d left her alcoholic second husband, Mike’s stepdad; moved with Mike into a rented duplex; and filed for divorce. Now she was behind at the office. “Sure, Mike,” she said. “But I’ve got a little bit left here. I’ll be there in thirty minutes.”

She was wrapping up one last bit of paperwork, filling out a bank slip to speed up a morning deposit, when the phone rang again. “I found my ride, Mom,” said Mike.

“Great,” she said. “You two wait for me at the house, and I’ll take you to dinner.” Three minutes later, she was out the door.

On the drive, she heard a traffic reporter on the radio announce a single-car collision on Pinnacle Road that had resulted in one fatality. Pinnacle was the shortest route from the high school to her new place. Depending on where the wreck had occurred, she and Mike would likely both pass the scene. Just as she had guessed, when she drove by Pinnacle, she saw a crowd gathered around several police cars and an ambulance.

But then she got home to find an empty driveway, and suddenly she was scared. She hurried to the accident and recognized the car folded around a street light. She ran to a police officer and told him her son had been riding in it, but in the commotion, he misheard her. “Don’t worry,” he said. “The driver just broke his arm. He’s been taken to the hospital already.” That meant the fatality she’d heard about was Mike. All her life, Sherry had imagined that losing a child must be the worst pain a person could know. Now she was living it. She collapsed unconscious in the street.

The despair was overwhelming, all day and every day. Mike was her only child. Her husband was gone, her mother and her first husband, Mike’s father, were both deceased, and she was estranged from her own father. Sympathy from friends brought no comfort. When her best friend said, “If it were my daughter, I couldn’t make it, but you’re strong, you’ll pull through,” Sherry could only wonder why it wasn’t okay for her to fall apart. Because that’s what she felt herself doing. She was completely alone.

Two weeks after the accident, a neighbor told her to call Will Spong. Will was an Episcopal priest, seminary professor, and grief counselor. When she reached him, he skipped past any small talk.

“Here’s what I need you to do,” he said. “Get Mike’s suitcase. Take it to his room and fill it with everything that mattered to him: his books, his records, toys he played with when he was little. Get a scrapbook with pictures of him. Then I need you to bring those things to my office. I’m free all this Sunday, and if you can come then, I’ll set the day aside for us. We’ll look at his pictures, read his books, listen to his music. Before we can do anything, I’ve got to know who Mike was.”

She was there that Sunday. Whatever she might have expected a priest to look like, Will wasn’t it. He met her in street clothes, a big man, six-foot-four, with a healthy middle girth and long, thin limbs. He had dusky blue eyes, a thick brown beard, hair over his collar, and a subtle North Carolina lilt to his low voice. His office was softly lit and decorated with seventies hand-me-downs, overstuffed furniture covered in worn leather and corduroy. One long wall was lined with floor-to-ceiling shelves cluttered with books, records, and, oddly, dozens of plush toys and figurines of frogs and circus clowns, some peeking around a banner hanging from the top shelf that displayed a lyric from the musical Zorba: “Life is what you do while you’re waiting to die.”

Sherry showed Will her son’s sophomore class picture. They spread Mike’s letter jacket out on the coffee table and sorted through his old Legos and Star Wars figures. They passed a guitar back and forth that he had just begun learning to play. They put “Walk of Life,” by Dire Straits, on repeat on the stereo. And they cried. A lot.

Sherry started seeing Will at least once a week, and the discussions never got easy. She wrestled endlessly with “if onlys” and “whys.” She was mad at herself, at her ex-husband, at the driver, and, most painfully, at God. She’d been raised a good Methodist. When she was little, she’d read prayer books every night before bed, lest something bad happen the next day. Now God had either taken Mike from her or done nothing to save him.

“How could God kill a good kid?” she asked during one session. “Why are there bad kids still living when Mike is dead? God made a choice!”

“You think the bad kids should die and the good kids should live?” Will replied. “God didn’t keep his own son from getting killed.”

“Don’t push me!” she snapped back. “I’m alone! Forever! And I don’t want to go on living! But if I kill myself, God won’t let me into heaven, and I won’t see Mikey again!”

“It looks like you’ll have to live, then. But you’re afraid of living . . . and you’re afraid of dying. So what’s next?”

“Don’t tell me it’s going to get better. Don’t tell me Mike would have gone to college in two years and I would have lost him anyway. Don’t tell me his death served some purpose.”

“I wouldn’t. I don’t think his death served any purpose.”

“You’re not helping me.”

“You’d rather I tell you what you want to hear?”

They were both in tears. “Look,” said Will, “you believe some things, and you feel some others, and they don’t connect well. But I don’t believe you’re responsible for Mike’s death. I don’t believe the driver is responsible. And I don’t believe God is responsible. Mike died because his head hit a light pole. It’s not meaningful, but it’s true. I could tell you that God is a tyrant, but I don’t believe that. I think death just happens.”

Sherry fell silent. She and Will would continue the conversation for the next three years. Eventually she’d be ready to start living again. She’d speak to Will’s seminary students about what she’d been through. She’d remarry, in 1991, and Will would perform the ceremony. But in this one moment, the darkness was too great to see through to any of that.

Finally she said, “I’m sad.”

“I am too,” said Will.

Will Spong was my father, and when I was growing up I took real pride in his reputation around Austin. He didn’t have his own church, but Episcopal congregations knew him as a must-see guest lecturer who played piano while he taught. “The Gospel According to Oscar Hammerstein” was a greatest hit. Some of those churchgoers also knew him as the interim rector who came in when churches were in distress: when a priest died or, just as often, when a warring congregation drove one out. Dad had a way of telling the truth that didn’t leave scar tissue, of getting people to agree to disagree. That accounted for his place in Austin’s counseling community as well. When a therapist working with a couple identified a rift too great to mend, the two were often referred to Dad. He was the counselor to help them make a clean, healthy break.

At Austin’s Seminary of the Southwest, where for thirty years he taught pastoral theology—the nuts and bolts of how to apply faith to caring for people—he was known as “the Will of God.” It was an especially good joke, given that his unwavering message, in the classroom and at the pulpit, was that no one can ever know God’s will with any degree of certainty. To his mind, human understanding of God is necessarily limited, and it’s too often used as leverage over others, to demean, exclude, or otherwise diminish them. “We are all made in God’s image,” he used to say, “and ‘all’ means all.” It was a theology of humility and grace, and a less facetious distillation of it showed up on T-shirts some students made one semester and wore around campus. In big block letters, they announced his oft-repeated, bottom-line truth: “God is God and I am not.”

At home, on the other hand, he was just Dad, and as far as I could tell, being a preacher was just his job. For one thing, he had a way of cursing when he discovered dog mess on the kitchen floor that demystified the word “priestly” for me. But also I had numerous friends from more outwardly religious households, even though their parents weren’t clergy. The Spongs said grace before meals but not in restaurants. We attended services most Sundays, but we were Episcopalians: there was no expectation that we be at church for midweek expressions of our faith. The most conspicuous that Dad’s work ever was at home was when he spent all day Saturday working up a sermon or weeknights on the phone with people having a hard time.

What he was doing for those callers became clearer to me as I got older, especially after he died, in 2004. The early letters that came in from grateful former students, clients, and colleagues were somewhat expected, yet they never quit coming. Even now I get at least one email a year out of the blue and from a complete stranger, someone who wants me to know the impact Dad is still having. A Waco psychologist wrote that his counseling career was shaped largely by one conversation with Dad in 1973. A couple whose eighteen-year-old son was killed by a drunk driver in 1999 told me that the grief would likely have destroyed their marriage if they hadn’t worked through it with Dad.

They were powerful stories, but I don’t think their gravity ever fully settled. I could understand them, but I couldn’t feel them. Then one afternoon last fall I was checking out at the grocery store and visiting with a clerk who’d rung me up a dozen times. Apropos of nothing she said, “I didn’t know your father, but I’ve heard he helped a lot of people. I heard that if someone lost a child, he was the person to talk to.”

Sitting in the grocery cart was my seven-month-old son. He’s my firstborn, the wondrous end product of a three-year-long miracle of medical science that parents in their mid-forties—like me and my wife, Julie—often have to rely on. At that precise moment he was fiddling with a tiny rag doll. I watched him stick it in his mouth and look up like he wanted me to know he’d figured out where the rag dolls go. “Wow,” I said to the clerk. “This is Will Spong’s grandson, Willie. That’s a great thing for him to hear. And me too.”

It was not, of course, Willie’s introduction to his granddad. I’d put Dad’s portrait in the nursery well before Julie and I brought Willie home. It’s on a nightstand between his crib and the old rocking chair Dad used to sing me to sleep in. All I really knew about my own paternal grandfather, who died when Dad was nine, was that he drank too much and, like my father, played piano by ear. Beyond that he was a stranger. I didn’t worry about that happening with Willie. When I held him, snapshots of me in my dad’s arms would pop into my head, pictures I hadn’t seen in years. I had this strange feeling that I’d known Willie my whole life; he completed me. I remember friends joking after they had kids about a terrifying moment when they realized that this little life was dependent on them for everything. I never experienced that. When Willie looked at me I saw trust in his eyes. It felt well-placed. And entirely familiar.

The idea that something could happen to him is one I can’t have in my head; the depth of the love I feel has to be the only insight I ever get into the depth of that loss. And it’s just as hard for me to imagine that anyone could say anything to help a person through that.

But then I think of Dad as I knew him. I remember long-ago conversations, things that he said that made my head swim at the time, things I can’t wait to tell Willie now. There was a night when I was eleven, and Dad and I were on the couch watching the baseball playoffs on TV. The Yankees had just taken the American League pennant by beating the Royals for the third straight year. But instead of showing the Yankees celebrating, the cameras lingered on the Royals’ shortstop, Freddie Patek. He was a small guy, not much bigger than I was, and he was sitting on the bench by himself. His feet barely reached the dugout floor, and he held his face in his hands, crying.

“Dad, why do they keep showing Patek?” I asked.

“Because the losers,” he said, “are always a whole lot more interesting than the winners.”

Dad had only one eye. But the glass one was such a close match to the good one that I never could tell them apart. He always said the way to recognize the false one was that it was the one with the glint of human kindness in it, a joke he attributed to my mom. The only way I could tell was to remember an evening when he failed to pick me up from Little League practice on his way home from work. Standing on the assigned street corner, I saw him coming from two blocks off. First I waved and then I jumped up and down—and he drove right by. It turned out I was waiting in a massive blind spot. From then on I remembered that the false eye was on the driver’s side of his face.

It was a disability, but he had fun with it. When my two younger brothers and I were little and Dad went out of town, he’d leave his spare false eye on the breakfast table with a warning that if we misbehaved for Mom, he’d see. When we were older and had friends over for dinner, we’d coax him to clink a beer bottle against the glass in his eye socket. At some point a story drifted down about a seminary cocktail party at which Dad quietly popped his false eye out and snuck it into the highball of the faculty’s erudite professor of systematic theology. “My gin and tonic would appear to be staring back at me,” remarked the esteemed Dr. Green.

There were other occasions, however, when the matter of his eye was less light. When Dad groused about not getting half off at the optometrist, he didn’t laugh. He quit playing catch in the yard with us once we got strong enough to put any velocity on our throws. And he wouldn’t take us to baseball games unless he got seats behind the foul-ball net. The few times that policy wasn’t followed were tense. Eventually, we stopped going.

He’d lost his eye at a baseball game in the summer of 1961. He was doing parish work at two churches in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, his first jobs out of seminary, and one night he went to watch some of his youth group boys play American Legion ball. He was talking to some dads just beyond the first-base dugout when a foul line drive smashed squarely into his left eye socket. His eye burst like a grape under a hammer blow.

The recovery was slow and painful, and not just physically. His father’s death had made him acutely aware of life’s fragility and unfairness—his father hadn’t believed in life insurance, his stay-at-home mother quit school at the age of fourteen, and Dad, the youngest of three, had been left to take care of her after his sister and brother moved out—but he’d tamped those lessons down to keep himself upright. A freak accident in a place as friendly as a ballpark will unlock all sorts of pent-up memories and emotions, and they’ll be hard to rein in from a hospital bed in bandaged darkness. The encouraging words he kept hearing from well-meaning parishioners and colleagues didn’t help. They’d throw him little bits of theology. “God never gives us more than we can bear,” they’d say. “You’re lucky to be a person of such strong faith.”

One friend who checked on him frequently was the bishop who’d sent him to Rocky Mount, Thomas Fraser. Fraser was a huge figure in Dad’s life; when I was little I considered him to be one of Dad’s heroes. A formal black and white portrait of him hung in every office Dad ever kept. When Fraser died, in 1989, Dad preached a sermon praising him as one of the few sixties-era leaders in the Episcopal church in the South who’d stood up to segregationist congregations. But it was only years later, after Dad had died and I’d talked to one of his old colleagues, that I understood Fraser’s real significance to him.

While recovering, Dad confided to the bishop that the things people were saying were making him feel worse, not better. “I don’t feel lucky at all,” Dad said. “This actually feels like more than I can bear. And I don’t know what to do with that.” Fraser listened. And perhaps he realized that if theological crutches weren’t helpful to Dad, then Dad might be a good person to talk to other people for whom they weren’t enough. “I’ve got a new job for you,” said Fraser. “There is a chaplain spot open in the pediatric oncology unit at Duke Medical Center. I want you to take it.”

Dad did, and there the story dovetails with one he did tell me. He started at Duke soon thereafter, before his false eye had been made, before the socket had fully healed. He walked the hospital with a black eye patch on, talking to sick kids and sitting with scared parents. He was still a mess inside; the eye patch and pain were constant reminders of a terrible thing.

One day, a six-year-old cancer patient looked up at him and asked, “Are you a real pirate?” Dad said everything got easier in that instant. His awful, irreparable loss was a connection to another person.

I loved going to church with Dad as a kid, especially when he preached. My brothers and I would sit toward the front, and he’d always mention us. When he referenced lyrics from songs we’d heard in the house, we felt as if he was teaching things we already knew. Of course, his sermon’s ultimate lesson typically sailed over our heads, but the car ride home was where things got explained. Not that it helped. I remember once, when I was maybe ten, asking him about the Trinity. “I get that God is God,” I said, “and that Jesus is his son, but who’s the Holy Spirit? I don’t get it.”

“To be honest,” he said, “I’m not sure I do either.”

“But you’re a priest.”

“I am. But that’s a tough one. I wouldn’t worry about it, though. I don’t believe the Trinity is the point.”

This made no sense. I’d been to church with friends where congregations spent half the service holding up three fingers. Keeping the Trinity front and center seemed to be the whole deal.

“Different churches and different people believe different things,” he said. “And I believe there are other things in the Bible to concentrate on. Like ‘Do unto others as you’d have them do unto you.’ Everybody can get that.”

I should point out that Mom was seldom in the car with us. She worked nights at the state hospital, and Saturday was the start of her work week, so she’d sleep in Sundays while Dad took us with him. They’d met in Virginia when he was in seminary and she was a pretty brunette nursing student. Sherry Pauley was from a tiny town in Kansas, where she’d grown up in a log cabin near oil fields her dad worked. Her mother had died when she was fourteen, and Mom’s response had been to steel her backbone. She abhorred debt, was constitutionally organized, and was always planning ahead. The food in her pantry was arranged alphabetically in rows she never let shrink below three cans deep. Dad always said that his mother never recovered from the death of her husband, that all she did was sit and cry. Mom was the antithesis of that. She and Dad married a week before he was ordained, in 1959, when he was 25 and she was 23. And after they divorced, just shy of thirty years later, he often said, “It’s no mystery why I married a Midwestern stoic.”

They were both workaholics, and after moving to Rocky Mount in 1960, they learned they couldn’t have kids and buried themselves in their careers. They were living in Durham when, in early 1967, they adopted me at the age of four months. Two years later, they adopted Patrick, and two years after that came a surprise pregnancy and the birth of a youngest son, Charles. In 1972 Dad took the seminary job and moved us to Austin.

His hiring was not without controversy. The first choice to teach pastoral theology was usually a parish priest, someone versed in leading a congregation. Dad was a hospital chaplain who had tended to people dealing with death. He’d taken over Duke Medical’s clinical pastoral education program, or CPE, in the mid-sixties, supervising students who were learning to do the same. The seminary’s concern was that CPE chaplains were typically more interested in counseling than teaching. They also had a tendency, after years in the murk of other people’s loss, to lose their faith.

But two years earlier Dad had preached at the ordination of some new priests in Greensboro. He’d built his sermon around lyrics from The Fantasticks: “Without a hurt the heart is hollow.” He warned the young men—all priests were male then—that they were entering a world of crisis that the church didn’t often have the courage to address. “The ministry may be many things,” he said, “but it is not an attempt to make every man happy.” Priests had to be willing to take unpopular stands. They couldn’t die for fund-raising targets or the demands of arrogant vestrymen, but they had to be ready to die for the gospel. That would require honesty, with their congregations and themselves. “Do not be afraid to hurt,” he preached, “do not be afraid to have pain; for in so doing you will hang in constantly as redemptive people in the process of life.” The sermon was published in the Virginia Seminary Journal, and after it was distributed to the faculty in Austin, Dad got the job.

The faith he discussed at school was the same one he described to me in the car. Back then, the Seminary of the Southwest was considered a progressive outpost of the Episcopal Church, and Dad fit right in. He didn’t put stock in an active hand of God. Not that God is powerless to act, but that’s just not what God does. The idea that God punishes or rewards or has a Plan is an assumption that God works in the world the way we do. “God doesn’t do,” Dad would say, “God is.” And as such God is present in all of human experience, be it suffering or joy, not as a protector from any of it but as a partner in it all.

He didn’t read the Bible literally, but it held profound meaning for him. He expressed skepticism when he talked about the specifics of Jesus’s miracles, but he’d point out that they were performed among the poor and marginalized. When I asked once about Lazarus, the man Jesus brings back from the dead in John’s gospel, Dad said the story’s great lesson was not that resurrection but Jesus’s reaction when he came to Lazarus’s grieving sisters: he wept with them. “For so many people, Jesus is about saving us from sin,” Dad told his students, “which I think exempts us from what it means to be human. Traditional theology teaches that God sent his son to die. And he did die, just like everybody else. But if there’s a salvific piece of the narrative, it’s that Jesus came to show us how to live.”

But Dad’s job wasn’t to make students believe what he did. He was teaching them to communicate their own faith, and to that end he did insist that they ground their ministries in contemporary life. He led a seminar on the New York Times, in which students had weekly discussions on everything from scriptural parallels for world events and how to chaplain the people involved to the ethics of the ads. He taught a class called “Film as an Occasion for Prophecy and Perception,” in which students wrote reviews for a hypothetical church bulletin analyzing spiritual themes in movies like Do the Right Thing and A Clockwork Orange. The graphic violence of the latter prompted strong protest from some students, but Dad told them to write about it anyhow. In his view, confronting harsh realities was a nonnegotiable obligation of a life of faith.

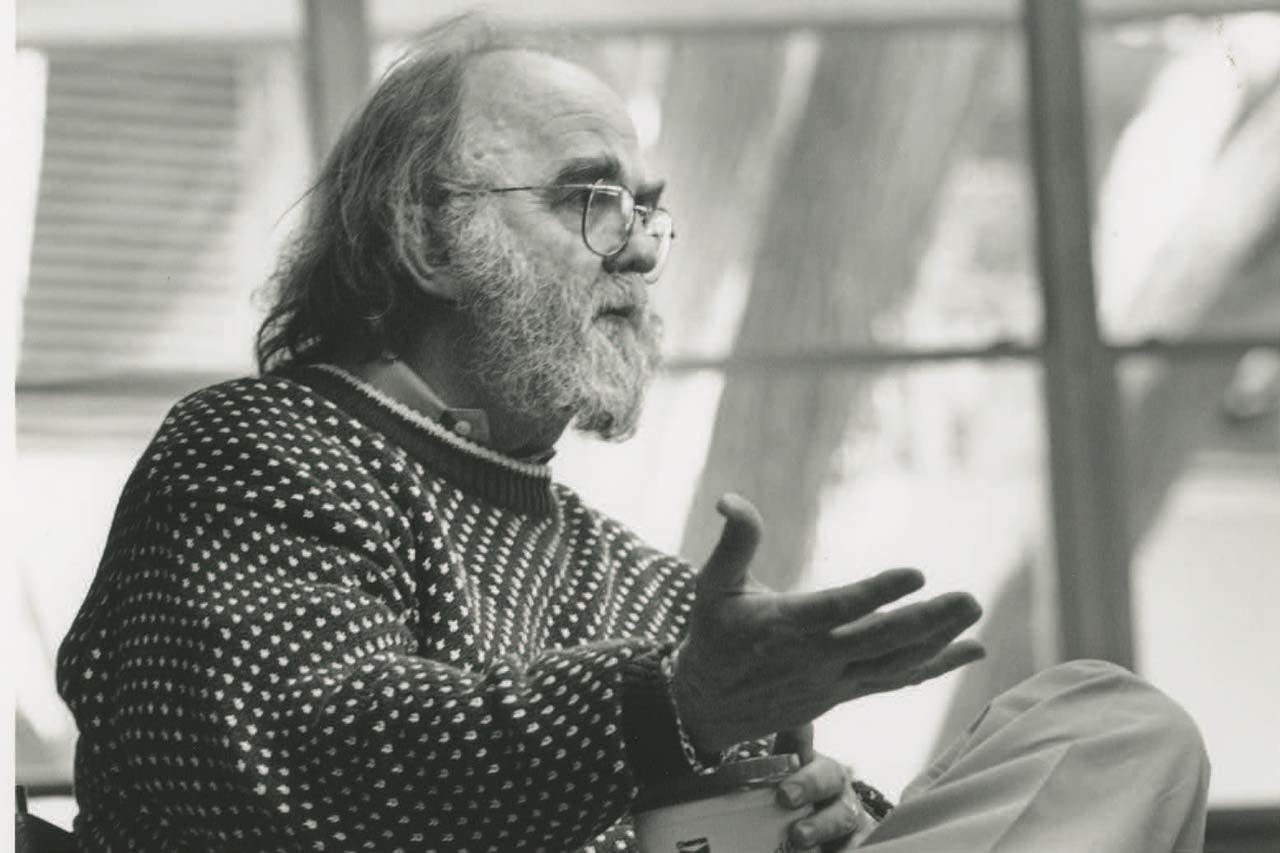

That was the point of his Greensboro sermon—and of his entire career, really. There’s a video in the seminary library of a presentation he gave to incoming students in March 2001, two months before he retired. I could have roughly guessed the year from the opening shot. His hair is to his shoulders, his beard is unruly and mostly white, and he’s wearing his autumn-years uniform: a button-down shirt, fleece vest, and khakis. Also, he’s standing at a piano. Most of his latter-career students and friends didn’t realize he hadn’t always played one during lectures. It was only after he fell in love with my stepmom, Nancy Whitworth, whom he married in 1992, that he summoned the nerve. She was in the audience with the new students that afternoon.

He begins with a song he calls an invitation to theological study, “Alfie,” from the 1966 film of the same name. Before he starts playing, he describes the movie’s plot. Alfie is a cheerfully unrepentant womanizer running through a series of destructive relationships in swinging London. “He moves in with a girl,” Dad says, “she becomes pregnant, and one day he comes to her flat and finds the unflushed remains of an aborted child in her toilet. So he leaves”—Dad waves his hand to whisk Alfie out the door, then sits at the piano—“and as he walks down the street, against the backdrop of the consequences of his own behavior, this song is introduced.” Dad plays slowly and speaks the lyrics. “What’s it all about, Alfie?” The melody lolls under the words—“. . . and if life belongs only to the strong, Alfie . . .”—until he arrives at the crux, at which point he stops playing and jabs at the air with his index fingers.

As sure as I believe there’s a heaven above, Alfie

I know that there’s something more

Something even non-believers can believe in.

His hands go back to the keys, and he starts playing again. “I believe in love, Alfie . . .”

Dad ends abruptly, as if he’s embarrassed that people might be admiring his playing. “I think that song’s fantastic because it looks on the face, not of religion for God’s sake, not at syrupy, pious little God talk, but of the common denominator of human experience. It asks, ‘Who the hell are we?’ and ‘What’s it all about?’ And if you’re not asking those questions, if you’re just here to learn how to put the vestments on right, go home. Don’t come here for that. The world is too important.”

When Sherry Taylor visited with Dad’s students, they weren’t taking his newspaper or movie review seminars but rather the CPE program he’d started at the seminary. When I met her for coffee one afternoon last summer, she told me a little of what she’d said to them. She didn’t describe how Dad had healed her, because that’s not what he did. “At some point it just came to me that everybody dies someday,” she said, “and I grabbed onto a little thread of hope that there’d be some happiness here. Life will never be like it was before Mike died. There’s always a gray haze over the brightness. But there’s a reason to be here, a purpose that justifies going through this.”

Dad continued to lead CPE even after he retired, and it’s the course his old students talk about the most. For ten weeks each summer, a small group of them would be assigned to an Austin-area hospital. They’d convene at Dad’s office for three hours in the mornings, then spend afternoons and evenings as chaplain interns in emergency rooms, intensive care units, and oncology wards, anywhere in the hospital they were needed.

The work was emotionally grueling, and the morning conferences weren’t much easier. The students had near-daily writing assignments, things like hypothetical letters to a friend whose spouse had committed suicide but more often papers that Dad called “verbatims.” After meeting with patients they’d write a short, anonymous medical history, the truest transcript of the conversation they could recall, and a description of their own feelings during the encounter. Each morning they’d present those to the group for feedback.

Students learned quickly that the real purpose of CPE was identifying the thing within themselves—a trait, belief, or piece of personal history—that might stand in the way of being an effective pastor. One of the first preconceptions they often had to get past was the common notion of what chaplains do. Dad had a number of blunt rules of thumb. “A clergyperson who walks into a hospital room and offers to pray is a clergyperson who wants to leave” was one. “A death is not an evangelical opportunity” was another. He had experiences to back them up. “I once worked with a woman whose thirteen-year-old son had cancer. Her church sent her a letter that said, ‘If you believe God can move a mountain, He can. If you believe God can heal your son, He can.’ A week later, her son died. And then she had to deal not just with the loss of her child but with the feeling that some failure in her faith had caused it.” Still, Dad also had patience. If a student mentioned God’s plan in a verbatim, he would hear him or her out, then ask, “How is bringing that up going to help?”

He was steering students away from the impulse to make things better. A crisis counselor’s job is to listen, not to fix a person’s grief or pull a lesson from it but rather to hold it with them, to be there in their suffering. In therapist-speak that role is referred to as a “non-anxious, nonjudgmental presence,” and it requires being comfortable amid pain. Most people can’t do that. It’s the reason they just drop off casseroles.

Finding that level of comfort was the hard work of CPE. When verbatims were honest and reflective, when students exposed the fear they’d felt with patients or the memories that informed their conversations, the morning discussions would morph into something akin to group therapy. They had to. A student who’d grown up with an alcoholic or abusive parent had to be aware of any vestiges of a victim’s mind-set. If one was wrestling with his sexuality, he had to address that before talking to a dying AIDS patient, which was a huge part of hospital work in the eighties. Students had to realize that a chaplain’s conversation with a patient could never be about the chaplain.

One student who went through that process toward the end of Dad’s career was a woman named Evelyn Hornaday. Her husband had died in 1997, two months before she and her 25-year-old son moved to Austin from Missouri so she could begin seminary. A year later, she took CPE. “I’d give my verbatim and start crying in the middle of it,” Evelyn told me. “I was still too wrapped up in grief for my husband. Once I’d catch my breath, your dad would say, ‘Go on.’ It was like we had this silent covenant. That was going to be my experience that summer.”

Evelyn graduated two years later, and a week before her ordination, her son, Jeremy, was badly hurt in a car accident. The injuries proved fatal. “The first person I called from the hospital was your dad. He came and sat with me for six hours while Jeremy was dying and never said a word. He stood beside me when they took Jeremy off life support. He put his arm around me briefly and then went out to the waiting room.”

Two months later, she was readying to leave for a church job back in Missouri when she ran into Dad on campus. He asked what she planned to do with Jeremy’s ashes. She was going to take them with her. They were secure in a good box that she wouldn’t trust to the moving company. They’d ride next to her in the car up to Springfield.

“He said, ‘Oh, no, you’re not,’ and I thought he was joking. Will Spong never said, ‘No, you’re not.’ ” But he pushed her. He was no longer in counseling mode. He was a fellow priest, a friend of hers and of Jeremy’s. He told her she was already taking enough grief to Missouri. Austin was where Jeremy’s home and friends were. He’d been an artist, and Austin was where he created. It was where he lived.

She half-jokingly asked what he thought she should do. “I’ve already talked to Nancy about that,” Dad said. “She’s got a boat on the lake. The night before you leave, we’ll take Jeremy and a bottle of wine upriver, and you can release him.”

Then he got theological, Evelyn said. “He talked about the water of life rolling on. He said, ‘Think of Jeremy in each drop of water, think of all the shores and people he’ll reach. Think about giving him back to creation.’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ He said, ‘Think about it.’ ”

The night before she left Austin, Evelyn drove Jeremy’s ashes to Dad and Nancy’s house, then they all went to Lake Austin and motored upstream. “It was a lovely evening,” she said. “At about nine o’clock the sun went behind the hills, and I said, ‘It’s time.’ Nancy slowed the boat and turned it around. Your dad blessed the ashes, I kissed the urn, said my goodbye, and emptied it behind the boat. Your dad and I cried all the way back to the dock, each of us sitting on our little corner of the backseat. Then we drove back to their house in silence. I got in my car, waved goodbye, and that was the last time I saw Will Spong.”

Dad died February 3, 2004. When I found him in bed the next morning, I thought he was just sleeping. He was curled up on his side, with a pillow between his knees, a quiet remove on his face, and the television tuned to CNN. I guessed he’d drifted off watching returns from the Democratic presidential primaries, and I wondered if he’d stayed up late enough to see that his candidate, John Kerry, had all but swept.

A fortuitous series of events had put me in the room at that moment. Eight months earlier I’d moved onto the property where he lived with Nancy. It was a shady one-and-a-half-acre spread one mile south of downtown that they’d bought shortly after they married. Their home was a converted 150-year-old gristmill, and the garden outside their bedroom window was on a dry creek bed below street level; when a hard rain hit they could hear a small waterfall in the grotto from their bed. I rented the smallest of four outbuildings, which meant I ran into Dad in the driveway a good four times a week. When Nancy was out of town, he’d take me to dinner.

She was on a trip in South Texas when I found him. I’d spent the previous night writing at the office until 4 a.m., then come home and slept in. So I was there when his office assistant called and said he hadn’t shown up for his first counseling appointment. She asked me to check on him.

When I walked in, I said, “Hey, Dad,” and gave him a nudge. His skin felt clammy, which I recognized from giving him back rubs when I was little; every Saturday night, I’d rub his shoulders while he watched Carol Burnett—one dollar for doing it, two if he fell asleep. But he also felt cold. I shook him, and his body didn’t give. I checked his breathing, and he wasn’t; I felt for a pulse and found none. His face was ashen.

I took a few steps backward and leaned against the wall. “So this is that,” I said, and slid to the floor. Time slowed to half speed as I sifted through my emotions. It seemed like everything he’d ever taught me had prepared me for this moment—death is a part of life. I decided to soak it in. I could hear birds in the garden and smell juniper from a bowl of potpourri. I was grateful to be the one who had found him, that the end had been sudden and peaceful, in a place that he loved. But those thoughts struck me as trite silver linings. Dad used to say that the way people lived was more important than the way they died. I looked at the framed pictures on his nightstand, a portrait of him and Nancy by her baby grand piano and a shot of the three sons on Patrick’s wedding day. I thought about how the last decade of Dad’s life had been by far the happiest, but I knew he was in no way ready for it to end. None of us were. I looked back at him, cried for a while, then finally said, “Thanks, Dad. I love you.”

Ten minutes later I stood up, and whatever poetry the morning held took a quick turn. I called 911 on his bedside phone. “My dad seems to have died in his sleep,” I told the dispatcher, then gave her the address.

“Have you tried to revive him?” she asked.

“Oh, he’s pretty dead.”

Her tone sharpened. “You need to perform CPR. If he’s not on his back, put him there.”

I struggled to roll him. His body had stiffened, so his arms and legs were now sticking up in the air. Before, he’d looked like he was sleeping peacefully. Now he looked like he was falling.

“If his mouth is closed,” she said, “you need to open it.”

I noticed that the tip of his tongue was sticking out and explained that. “You need to open the airway,” she said. “Put down the phone, open his mouth, press down his tongue, and blow.”

My neck creaked through an exasperated 360-degree head-roll. I got on one knee, put a hand on his chin, and just then heard sirens outside. I picked up the phone. “Your guys are here,” I said. “I’ll turn this over to them.” The first EMS tech through the door said, “Yeah, it’s too late for CPR.” I excused myself, went back to my cottage, and started making phone calls.

The rest of the week went as Dad would have scripted. We had a service on Saturday at Good Shepherd Episcopal. Dad’s brother, Jack, a retired bishop and one of the most important progressive theologians in the Christian church, deferred officiating duties to Dad’s closest faculty colleague, the Reverend Charlie Cook, so that the service would be a true seminary event. Instead Jack sat with us, then addressed a rapt audience from Dad and Nancy’s front porch at a reception that afternoon. An East Austin gospel group played after that. Several hundred people came, and it was strange to look at their faces and think that many of them had gone to Dad to learn to deal with events just like this one.

He had one last message for them. He’d written his own obituary. Though I snuck in one line—I wrote that he’d died “probably from heart failure,” knowing he’d appreciate the acknowledgment that we weren’t sure what killed him—the rest was all him. In four concise paragraphs he identified his decedents and survivors, degrees and jobs, and favorite sermon topics and songwriters. Then he closed by describing his beliefs about death. They were largely things I’d heard before: the Zorba quote, the T-shirt slogan, the plea for people to “live with the ambiguity of life and not be afraid to tell the truth.” But there was one line I did not know. It was by the playwright Robert Anderson: “Death ends a life but not a relationship, which struggles on in the survivor’s mind toward some resolution it may never find.”

Two more memories. As a teenager I did a remarkably thorough job of meeting people’s expectations of a preacher’s kid. Run-ins with teachers and school administrators were nearly constant, and there were also a few with police. Beer-drinking was typically a factor, but the incidents themselves—throwing snowballs at cars, throwing eggs at a buddy in the grocery store, and so on—got enough laughs in the telling that I never took any of it seriously. Dad, on the other hand, said that my drinking prompted him to significantly cut back on his own. I thought that sounded a little dramatic.

One Thursday night just before high school graduation, I went to a playoff baseball game in DeSoto, three and a half hours away. The game went extra innings, and I didn’t get home until after two in the morning. This was before cellphones, and I hadn’t checked in, but I also hadn’t had anything to drink. I expected a medal.

Dad was livid. I explained what had happened, patting my sober self on the back, which did nothing to calm him. “Do you know what I did today?” he said.

“Uh, went to work?” I replied.

“I spent all night in the hospital with a family whose son had been killed in a car accident. And then I came home and you weren’t here. And you never called. So then I spent the last two hours wondering if you might be dead.”

“Yeah, but I’m not, Dad,” I said. “I’m here. Why can’t you just be glad about that?” Such was the capacity of the preacher’s kid to get inside the mind of the preacher.

But one Sunday morning late last fall, Julie and I took Willie to church for the first time. She and I hadn’t been regular churchgoers. Her family didn’t go when she was growing up, and I’d slacked off mightily after Dad died. As we worked to start a family, however, finding a church was a priority for me that Julie understood. We chose All Saints’ Episcopal, a late-nineteenth-century limestone hall on the University of Texas campus, less than a mile from the seminary.

As I carried Willie from the car, I felt my eyes well and tears start to roll, and when we turned onto the path to the church steps, I stopped. It occurred to me that one Sunday morning a long time ago, Dad had carried me into church for the first time too. I thought about how much that must have meant to him, about how long he’d waited to share his world with his son. I put my free hand on Willie’s back and pulled him a little closer. I pressed his forehead to my cheek and closed my eyes. Then the three of us went up the steps and into the church.