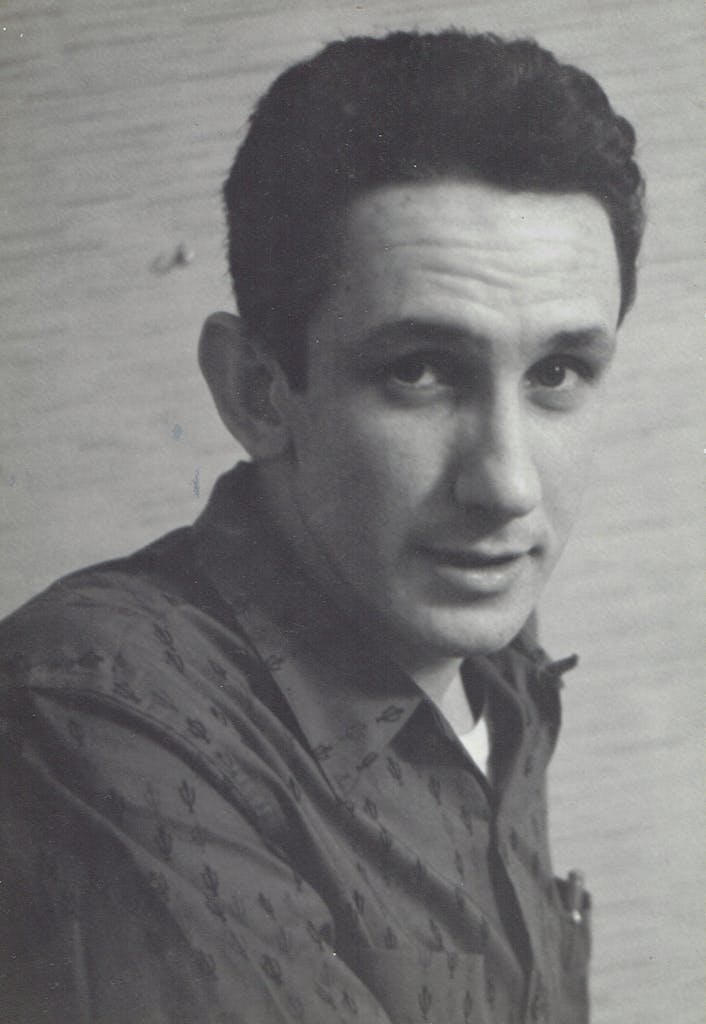

Robert Burton “Mack” McCormick—historian, folklorist, collector, musicologist, producer, songwriter, record label owner, journalist, and playwright—died on November 18 of complications from esophageal cancer at his Houston home. He was 85.

McCormick, known as Mack, lived his life on his own terms, lighting out for the territories to seek answers to things he didn’t know, whether it was why Houston’s Fourth Ward had so many barrelhouse piano players, or what Robert Johnson looked like, or how fantastic would it be to take a Texas prison gang to sing at a Rhode Island folk festival. “I am an anthropologist,” he once wrote. “That is to say I am involved in a study of mankind and his ability to cope and the style he brings to the job.” Indeed, Mack brought his own singular style to everything he did.

Mack was born on August 3, 1930, in Pittsburgh. His parents, Gregg and Effie May, were x-ray technicians, and his father worked for DuPont, traveling around the country showing doctors how to use x-ray machines. After they divorced, Mack grew up with his mother, who moved them around to Ohio, Alabama, Colorado, West Virginia, and Texas. He was living in Houston in 1949 and writing plays when he became the jazz correspondent for Down Beat magazine, interviewing everyone from Frank Sinatra to Duke Ellington.

He worked various jobs over the next decade—barge electrician, cook, carny—but it was when he started driving a taxi in Houston that he became enamored with all the different kinds of music he heard in the city. He soon began seeking out local musicians to record, ultimately working with heavy hitters like Lightnin’ Hopkins (whose career Mack revived in 1959), Mance Lipscomb, and Robert Shaw. He collected songs from other Houston artists too, which were released in Treasury of Field Recordings, Volumes 1 and 2.

Mack loved doing what he called field research, which meant knocking on doors and asking questions, or stopping in an unknown town, going up to groups of strangers, and starting a conversation with them. He’d hear songs, get recipes, learn local legends, and then he’d later type up his notes and file them away for future use. He put his skills to good use in 1960 when he took a job as a census taker in Houston, asking to be put in the Fourth Ward. During this assignment, he discovered more than 200 professional barrelhouse piano players, all of whom, he learned, got their chops from a man named Peg Leg Will, who once played on the porch of Passante’s, an Italian grocery store.

Mack became well known in folklore circles, and in 1965 famed folklorist Alan Lomax asked him to round up a group of singing ex-prisoners and bring them to the Newport Folk Festival. Mack wound up showing his pugnacious side during sound check, when the rollicking band onstage—the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, led by Bob Dylan—wouldn’t get off and give his ex-con singers (who had never performed together) a chance to check their vocals. “We need the stage!” Mack yelled at Dylan, who ignored him. So Mack unplugged the sound cables.

He was married by this time to Mary Badeaux, a Houstonian who worked at Baylor College of Medicine. He wrote stories for various newspapers and magazines, booked shows, and occasionally made money being a folklorist. In 1968 he was hired by the Smithsonian as a “cultural historian” when Texas had an exhibit at the summer Festival of American Folklife in Washington D.C. Mack gathered everything he could to show off his state, from quilts and recipes to dolls and handmade chairs. He also asked President Lyndon Baines Johnson to do a workshop and tell tall tales. The President came and told stories for fifteen minutes.

Mack was obsessed with great artists; more specifically, he was obsessed with the search for them. He was determined to find out more about Henry Thomas, a relatively unknown Texas singer who had recorded music in the twenties. Thomas, also known as “Ragtime Texas,” was a songster, performing early ragtime, gospel, reels, and blues. Mack spent years tracking him down, using imaginative detective work such as playing 78s for people and identifying the singer’s accent as coming from Upshur County in northeast Texas. When Herwin Records put out a Thomas compilation, it was accompanied by a 10,000-word piece by Mack, a loving evocation of Thomas, his music, and his time.

More famously, Mack spent many years on the trail of bluesman Robert Johnson, driving down the back roads of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, knocking on doors, and talking to hundreds of people, including a man who may have killed the bluesman. The search for Johnson took over Mack’s life, as he later wrote: “I’d become absorbed not as a matter of anthropology or aesthetics, but looking at him as a dark young fury that reveals something about the American experience.” Mack finally located the musician’s two half-sisters near Baltimore in 1972 and got the first photos of Johnson. He sat down to write what would be the definitive book about the bluesman, tentatively titled Biography of a Phantom, though he often thought of it as a detective story: Who Killed Robert Johnson?

The book never came, though, even as Johnson became an American icon, in large part because of Mack’s labors. It wasn’t the only incomplete project Mack abandoned. The Texas Blues, a mammoth project he had collaborated on with English scholar Paul Oliver, was also abandoned after he and Oliver had a falling out. Mack was a noted perfectionist, and he also suffered from manic depression, which drove him into doubt and debilitating self-consciousness. A creature of enthusiasms, Mack would set aside one project and pick up another. He sent much of his time over his final decades working on plays—including one on his favorite poet, Emily Dickinson, called Zero to the Bone—and receiving visitors, who came to talk first-hand to the man who had done so much to find and preserve American music. Mack loved to talk and tell stories, to grab his listener’s attention and whisk him down one of the paths he had taken decades before.

In his later years he tended toward solitude, withdrawing inside his northwest Houston home. He seemed happiest working on various projects, puttering around the house, and fielding calls from enthusiastic strangers—whether students and journalists or rock stars like Jack White.

Mack had been ailing for the past few years and was diagnosed with esophageal cancer in September. He chose to live out his final months at home, in hospice care, surrounded by his life’s work. He is survived by his daughter, Susannah, her husband, David, and their daughter, Emma.

A memorial service will be held on Saturday, December 12 at 12:30 p.m. at Dignity Memorial Oaks Funeral Home, 13001 Katy Fwy, Houston, TX 77079; 281/497-2210.