This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

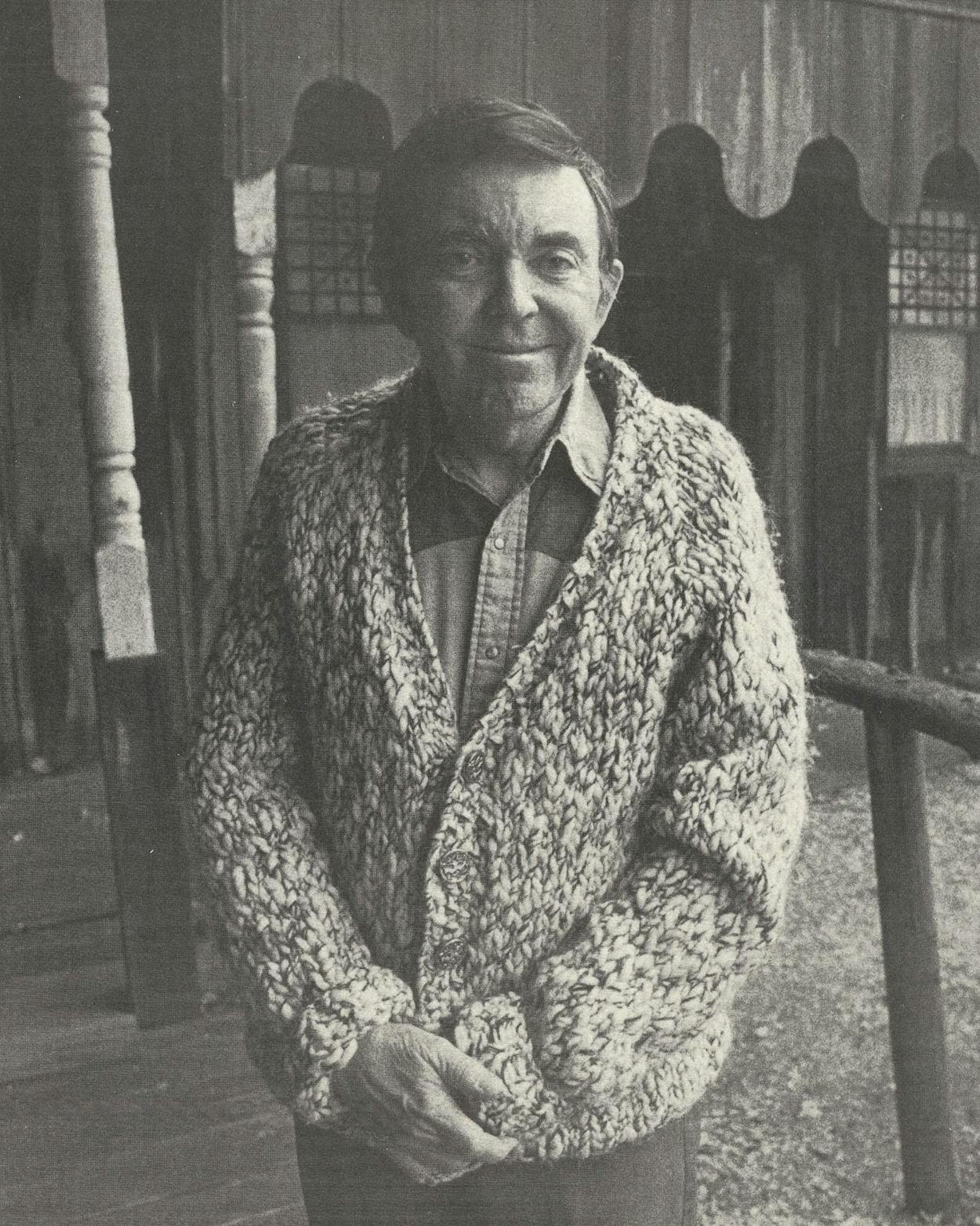

The first time I saw Gordon McLendon in person, I understood how Dorothy felt when she followed Toto behind the curtain in Oz. A good portion of my younger days had been spent hooked on one of McLendon’s Top 40 radio stations, and I’d heard so many of his editorials, newscasts, and promotions that I felt as though I knew him intimately. But the diminutive stranger sitting across from me in a sixth-floor office of the McLendon Building in downtown Dallas just didn’t fit the imposing image his voice had always conjured up. How could a voice so commanding and persuasive that it once made me forget that his station hadn’t played my request for “Dance, Franny, Dance” emanate from the body of this sleepy-eyed businessman in a three-piece suit with his feet casually propped up on his desk?

At least I had waited until an afternoon in late May last year to have my illusions shattered. By then, it was all over between Gordon McLendon and me anyway. A week earlier the McLendon Corporation had sold KNUS-FM in Dallas, its last broadcasting interest, to an outfit called San Juan Racing, Inc., for $3.75 million. The transaction formally ended Gordon McLendon’s long and mutually beneficial fling with radio. And even though my illusions had been shattered, I knew that radio without Gordon McLendon would be a whole lot duller for listeners like me.

My elders remember McLendon as the Old Scotchman, the semimythical broadcaster, supposedly 87 years old, whose vivid re-creations of sporting contests during the forties and early fifties were often more exciting than the events themselves. But to millions of baby-boom teenagers growing up in Texas in the fifties and sixties, he was the Daddy of the Big Beat, a folk hero as instrumental as Cleveland’s rebel disc jockey Alan Freed in popularizing rock ’n’ roll. More instrumental, really, because while Freed merely played rock, McLendon was the first to appreciate its commercial potential and to mold it into a salable package.

Top 40 was the package, and it established McLendon as a broadcasting industry legend—P. T. Barnum, William Paley, and Jesus Christ rolled into one. In 1954, when national radio sales reached the bottom of a five-year slump and the advent of television threatened the medium with extinction, Gordon McLendon led it out of the wilderness. In that year KLIF, the first McLendon station to adopt a Top 40 format, rocketed to the number one position in Dallas, attracting as much as 40 per cent of the available audience with an engaging blend of the forty most popular records of the week plus a smattering of news, chatter, and slapstick gags. From 1957 to 1965, Top 40’s peak years, 75 per cent of Texas’ population had a McLendon pop music station at its fingertips. KLIF in Dallas, KTSA in San Antonio, and KILT in Houston all garnered unprecedented ratings, generating huge advertising revenues and forming the cornerstone of modern radio’s greatest independent empire. McLendon’s sole peer in the art of Top 40 was Todd Storz, who is credited with originating the idea at his station in Omaha, Nebraska.

Kids like me, of course, didn’t care about profit margins or ratings. McLendon’s stations commanded our attention because the music, rapid-fire patter, and outlandish contests, promotions, and giveaways were aimed directly at us. Top 40 radio was the first youth-oriented mass medium. It spoke the teen language, shaped teen attitudes, and captivated teen imaginations. Like the rock ’n’ roll music it featured, Top 40’s pace was fast, exuberant, and crazy, an around-the-clock audio circus hosted by motor-mouthed lunatics known as disc jockeys or deejays, local celebrities whom we could hear, talk to on the phone, and even meet in person at the sock hop, drive-in, or record store. My parents may not have thought too highly of characters like the Weird Beard, Jimmy Rabbitt, Charlie and Harrigan (later imitated by KILT’s Hudson and Harrigan, who are still familiar figures to Houston teenagers), the Big R, and Mark E. Baby, but their off-the-wall jive and love of rock music made them stars in my book:

“All right, baby, this is Russ Knight, the Weird Beard, the savior of Dallas radio. Let me save you with music till midnight. Oh! I tell you, somebody’s got to come up here before midnight, honey, one of those Dallas good-lookin’ girls, and pull my Weird Beard tambourine. We got Billy, Roy, Dale, Trigger, the Dallas Salvation Army . . . ha! From Eleven Ninety at the harmonic tone [quack!] little music for Big D, lotta Weird Beard dances goin’ round Dallas, the Black Bottom, got a new dance from Joey Dee and the Peppermint Twist and it . . . goes . . . like this!”

Russ Knight

KLIF disc jockey, 1962

His deejays reigned as teen idols, and Gordon McLendon was the biggest star of all, because he made exciting radio possible in the first place. Not only did he shape and promote Top 40, he introduced the all-news and beautiful-music formats and developed such now-commonplace gimmicks as the Rear-Windo bumper sticker, 20/20 newscasts, mobile news units, and mnemonic call letters like KABL, KNUS, and WAKY. But the biggest difference between McLendon and lesser broadcasting executives was that he let his own personality permeate each station his family owned. As a sportscaster, he was the centerpiece of the Dallas-based Liberty Broadcasting System, which in 1951 ranked as the nation’s second largest, with 458 affiliates. Even after he began concentrating on the behind-the-scenes operation of the McLendon chain, he continued to read editorials over the air on each and every station, another industry first. Most of all, McLendon possessed a unique appreciation for radio’s power to stimulate the imagination as other mass media could not.

“In radio there is no sight,” he expounded to me that May afternoon. “One must therefore paint an image on the viewer’s mind. If you’re an artist at doing that, you can actually make that image much larger than life, much more colorful than reality.”

I wondered how, feeling as he did, McLendon could now divorce himself from his love of 32 years. At 58, he was leaving radio to devote his full attention to the McLendon Corporation’s extensive real-estate, movie, oil, and hard-money investments, claiming, “I have a better chance now of making a worthwhile career than I ever had when I was in radio.” But, no matter how many millions he’s making, how could he just turn his back on his first passion? As if in answer to my question, from the adjoining room an Associated Press teletype clacked out a noisy rhapsody of information, confirming that while Gordon McLendon might have finally crossed over into the corporate realm, his private world still sounded like the KLIF newsroom.

McLendon had always walked a tightrope between instinct and loyalty, between the promptings of his own flamboyant ego and the mandates of corporate responsibility. His father, B. R., and grandfather, Jefferson Davis McLendon, had imbued in him the drive to achieve, grooming him to follow in their footsteps as practicing attorneys. From them he inherited a flair for showmanship and a knack for making money in the entertainment business, a knack his progenitors had demonstrated by developing the extensive Tri-State movie theater chain from a small Atlanta, Texas, theater given them in lieu of a legal fee.

As an adolescent, Gordon McLendon was a model of ambition who would have made Dale Carnegie proud. At the tender age of twelve, he won a national contest with his essay “What I Would Do If I Were President.” He represented Atlanta High School as a champion typist and debater, edited the school paper, then worked as a stringer for several East Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma newspapers, and eventually started his own publication in Atlanta.

All those pursuits paled, though, next to his fascination with radio. His first memories of Marconi’s invention are of sports broadcasts by Ted Husing (“the best who ever lived”), Bill Stern, Mel Allen, and Graham McNamee—broadcasts that kept him glued to the family’s Majestic radio.

“I listened to those sports broadcasters and I just imagined how wonderful it would be to be in radio. This, after all, was the most important job in the world, not president of the United States. It was very romantic, as glamorous for me as getting into motion pictures would be for some.” After mimicking Husing’s broadcasts during frequent drives to nearby Texarkana to visit his girlfriend, McLendon made his broadcasting debut at the Atlanta Rabbits high school football games, where he used a public address system borrowed from his father’s theater to regale the spectators with descriptions of the action.

The year 1939 found McLendon enrolled at Yale. He majored in oriental history and languages but spent most of his spare time at the campus radio station, where he teamed up with an aspiring actor named James Whitmore to cover the school’s sporting events. After college he enlisted in the Navy and was trained as a cryptographer on the Pacific front. But even in the midst of a world war, he found time to present a daily five-minute seriocomic news commentary on the Armed Forces Radio Service under the nom de microphone of Lowell Gram Kaltenheatter. After his discharge, he enrolled at Harvard Law School but lasted less than a year before informing his elders that lawyering was not his destiny. With his family’s reluctant blessing and a loan from his father, McLendon returned to Texas in 1947 and purchased a half-interest in a small radio station in Palestine.

His introduction to the world of commercial broadcasting was a rude one. His duties at KNET included serving as program director, sales manager, janitor, and announcer of the Palestine Wildcats football games. Meanwhile, Jeff and B. R. McLendon moved the headquarters of their growing theater chain from Atlanta to Dallas, where they had constructed the Casa Linda Theatre two years earlier. It took only a few months for Gordon to realize that the Palestine station was small potatoes; he sold his half-interest and followed the family to Big D, enticed by the prospect of starting a new radio station there. The Federal Communications Commission granted the McLendons authority to broadcast one thousand watts of power over the 1190 AM frequency from suburban Oak Cliff during daylight hours, and in November 1947, KLIF went on the air.

KLIF’s early programming mixed the standard soap opera, sitcom, and drama fare left over from radio’s so-called golden era with a twist provided by McLendon’s sports knowledge and announcing talents. In those days major league baseball and football games were not broadcast regularly in the Southwest. McLendon decided to fill the void—and simultaneously skirt the expensive formality of securing broadcast rights—by recreating games himself. Typically, minimal accounts of actual contests, either from an observer at the ball park or from a New York correspondent who monitored that city’s three baseball teams on the radio, were fed by teletype to the KLIF studios in the basement of the old Cliff Towers Hotel. Armed with these rudimentary facts and tapes of crowd noise he had made at Dallas’s Burnet Field, McLendon painted stirring scenes of noble warriors battling mightily for victory—even though he had seen but one major league game.

“All my life I had built up these baseball and football people, the players, as being absolutely Kong-size,” he reminisces. “In my mind I pictured a fellow like Joe Medwick or Joe DiMaggio to be like the Colossus of Rhodes astride the plate, getting ready to take a swing. And you know, that larger-than-life image never gave way.”

Within a year McLendon created the Liberty Broadcasting System to carry his glorified accounts to other cities. Though the network ran other programming, sports was its bread and butter, and its primary personalities were sportscasters like Dizzy Dean, Lindsey Nelson, and the Old Scotchman. Recognizing Liberty’s clout, the major league baseball clubs eventually granted the network rights to broadcast live from the stadiums, but McLendon continued to augment the on-the-scene coverage with re-creations. Reality, as far as he was concerned, was no match for the basement studio where his sound men (among them former Dallas mayor Wes Wise) tapped pencils on baseball bats to simulate hits and shouted into garbage pails to reproduce the echo of a ball park’s PA system. McLendon was at his best when the teletype broke down or reports from the site were delayed: he would launch into a florid description of a dog running loose on the field, a bloody fistfight erupting in the stands, or a record number of foul balls being chipped all over the stadium.

He never quite got sportscasting out of his system, either. One of his most memorable broadcasts was the 1979 Psychic Super Bowl, an imaginary game in which the outcome was predetermined by a panel of astrologers and seers. “Having announced so many real games in the past, it was only a small step forward to doing a game that had never happened at all,” he says. Unhampered by mundane reality, McLendon indulged in prose as purple as ever: “Franco Harris forward like a huge piston for about a yard or so, but then a bone-shaking tackle straight up by Randy White . . . treeeemendous collision, you can feel it from here. . . .”

In 1951 Sporting News recognized the Old Scotchman’s peculiar talents by naming him America’s outstanding football broadcaster of the year. But by the following spring, his days behind the microphone were numbered. Calling his broadcasts a threat to the survival of the minor leagues, which at that time were the sole breeding ground for major league players, club owners denied Liberty access to the ball parks. McLendon fought back, vowing to “win the battle against the diamond dictators,” but in the meantime, unable to do live accounts of games and beset with internal management problems, Liberty declared a $140,000 loss and folded in 1952.

Only KLIF survived the bankruptcy proceedings, though the McLendons owned stock in another station, KLBS in Houston, later renamed KILT. Although McLendon pulled together the smaller Knickerbocker Broadcasting Network, which operated only in Texas, and continued recreating some games, he concentrated on running KLIF, which the FCC had allowed to begin broadcasting 24 hours a day. He brought a bright, crewcut young executive named Bill Stewart to Dallas from KLBS, where Stewart had toyed with a primitive version of the Top 40 format. In May 1953, the program whiz introduced his crude Top 40 sound to KLIF. Using an old trick he’d developed in Houston, he inaugurated the new format by playing Ray Anthony’s Dragnet theme over and over one day, attracting the attention of B. R. McLendon, who, in ignorance of the ploy, flew into a rage and tried to break down the KLIF studio door. But B. R. wasn’t the only one who noticed. Within six weeks the marginal station in Oak Cliff, which before had won only a 2 per cent share of Dallas’s radio audience, captured more than 30 per cent of Big D’s listeners.

KLIF’s spectacular rise prompted other McLendon stations to adopt the Top 40 format. By 1957, WRIT in Milwaukee, KTSA in San Antonio, KILT in Houston, KEEL in Shreveport, WAKY in Louisville, WNOE in New Orleans, and KNOE in Monroe, Louisiana (the last two operated as Noe-Mac stations in conjunction with McLendon’s father-in-law, former Louisiana governor James Noe), were rocking under the McLendon banner.

Unlike the other outlets, however, KLIF received the constant attention and monitoring of its owner—to the station’s obvious benefit. All subsequent refinements of the Top 40 format were pioneered at KLIF, which was rightly hyped as “America’s most imitated radio station.” From 1954 to 1972 it dominated Dallas’s airwaves as the city’s number one station, a position that was solidified in 1959 when the FCC let KLIF raise its power to 50,000 watts. But the edge that kept KLIF on top was the kind of aggressive promotion usually associated with Madison avenue supersalesmen. With McLendon’s blessings, Bill Stewart dreamed up a series of promotional stunts that made KLIF the most talked-about station in Dallas.

His greatest coup was the Money Drop. One week before Easter, 1954, KLIF ran teaser announcements telling listeners to gather at Elm and Akard streets at five o’clock on Good Friday and “watch the skies.” At the appointed hour, with 10,000 people on hand, Stewart and two assistants dropped 250 balloons with money attached to them from an Adolphus Hotel window.

“Kids were climbing up the Adolphus with butterfly nets,” Stewart recalls gleefully. “It ended up that I had to leave town, had to sneak out the back door because the cops were waiting for me downstairs.”

The Great Treasure Hunt, a gimmick created in Omaha by Stewart and Todd Storz, was the first contest run by a Texas radio station to exploit the public’s lust for easy money. A $50,000 check was buried in a Coke bottle, and cryptic clues to its location were issued regularly on KLIF. The promotion proved so successful that what seemed like half the city was dug up and the FCC issued an edict prohibiting radio stations from staging promotions that would damage public property.

The law and the imagination were the only limits to a McLendon station promotion. Besides the usual free tickets, albums, cars, pizzas, and vacations, KLIF gave away a mountain in West Texas, a South Sea island (which was actually a papier-mâché version of paradise), and a live baby (which turned out to be a live baby pig). When deejay Jimmy Rabbitt arrived at KLIF, his debut was heralded by several junk cars overturned at strategic locations on Dallas freeways with the message “I flipped for Jimmy Rabbitt” attached to their undersides. When there was no event to trumpet, one was invented. Thus an unsuspecting listener might be enticed to visit a nonexistent place like the Western Carolina islands, “home of the fastest-growing of all sports—giant squid fighting,” or be convinced of the advantages of owning his own Army-surplus tank.

Even the news, downplayed by Todd Storz and other early Top 40 programmers, got the show-biz treatment from McLendon. Introducing mobile news units wasn’t enough: McLendon conjured up an entire fleet of newsmen by christening KLIF’s two vehicles Mobile News Units Four and Six. Similarly, beat reporter and mobile-unit driver Ron McAllister was styled “metropolitan bureau chief.” “I’d do traffic reports every five or ten minutes and people would think I was all over Dallas when I was really sitting in Lee Park in a mobile unit monitoring the police radio,” he confesses with a laugh.

When every other station in town began imitating KLIF’s news-on-the-hour concept, McLendon introduced 20/20 News, with reports aired twenty minutes before and after the hour. Once the competition picked up that innovation, KLIF streamlined its delivery with 20/20 Double Power News—two newsmen taking turns reading reports at breakneck speed. “The object was to get as many stories into a four- or five-minute segment as you possibly could,” explains McAllister. “I think Frank Haley and I had the record at one time. We read seventeen stories in three and a half minutes.”

Strangely enough, Gordon McLendon never cared much for the rock ’n’ roll music that anchored his stations. Memos criticizing some pop tunes as too raunchy or too black for the masses frequently circulated around the McLendon offices. B. R.’s personal dislike for pianist and vocalist Nat “King” Cole once prompted him to walk into the KLIF studios and smash a Cole record the deejay was spinning. But even “bad” music had its exploitation value. In 1967, after Bill Stewart’s young daughter asked for an explanation of the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” McLendon began a nationwide campaign to clean up rock lyrics. At his behest, all McLendon affiliates banned such obviously racy songs as the Kingsmen’s notorious “Louie, Louie.” The cleanup also swept away more ambiguous ditties like Peter, Paul, and Mary’s “Puff (the Magic Dragon)” (Puff was marijuana, the censors reasoned), the Ohio Express’s provocative “Yummy, Yummy, Yummy (I’ve Got Love in My Tummy),” Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” (her crime was shouting “Sock it to me”), and Petula Clark’s “Don’t Sleep in the Subway.” When the furor subsided and the publicity had been milked, KLIF and its sister stations quietly resumed their regular programming.

Through the years, McLendon kept his profile high by filing news reports when he went abroad on business, covering the Wimbledon tennis tournament, and getting thrown out of an anti-U.S. war crimes tribunal in Sweden in 1967. He satisfied his love of history and his penchant for recreating events with features like “Headlines in Time” and “Yesterday’s Sports Page.” He even brought the four McLendon children into the act, airing their news reports when they traveled abroad. His son, Bart, covered the Viet Nam scene for three months when he was only nineteen until a bout with dysentery brought him home.

At no time did McLendon demonstrate his relish for the microphone, though, more than when he read editorials. From the day he aired his first one, shortly after the FCC approved the practice in 1949, to the day he sold KNUS, he wrote, read, or endorsed more than five thousand commentaries. Occasionally his polemics even got the intended results, as in 1968, when his attacks on Charles de Gaulle created a ground swell of anti-French sentiment in the U.S. After McLendon described de Gaulle variously as an “aging French egocentric,” an “elderly nut,” and an “ungrateful four-flusher,” the French government sent a Washington embassy delegate to Dallas to issue four rebuttals, an act akin to being suckered into a game of three-card monte. Capitalizing on the resulting publicity, McLendon lashed back with heated replies to the French rebuttals. The embassy delegate, however, did not return.

McLendon’s managerial technique was no less dramatic than his announcing and promoting ploys. Defying a traditional broadcasting tenet, he surrounded himself with upper- and middle-level executives—such as Bill Stewart, Dickie Rosenfeld (who still runs Houston’s immensely successful KILT), Don Keyes, Bill Weaver, Bill Morgan, and Ken Dowe—who were experienced in programming rather than sales. McLendon reasoned that “if you keep your eyes on the programming, the sales will follow.”

He demanded the best from his employees, and even that often wasn’t good enough. In a memo he once called an uninspired executive “as thoroughly worthless as any living protoplasm could ever get.” The accused party agreed that McLendon was 90 per cent correct. “I was a pretty tough taskmaster,” McLendon concedes in a rare understatement. “But I believe that I both worked as hard as any of my employees and didn’t demand anything from them that I wasn’t able to do myself.” He ran his stations with an iron hand, sometimes firing entire staffs at once and replacing them with personnel from competitive stations in the same market. Not even the lowliest disc jockey was safe from his constant monitoring. Ron Chapman, now program director of KVIL-AM and FM in Dallas, first worked in the city at KLIF, under the name Irving Harrigan. One night during Chapman’s graveyard shift, McLendon phoned in to complain that the hapless deejay had just read the worst newscast McLendon had ever heard. “I told him he was exactly right,” Chapman says. “When I hung up I couldn’t help but think, My God, how does he do it? This man never sleeps. And there were some eras in his life in which I’m confident he didn’t.”

The McLendons continued buying and selling radio stations, always staying within the legal limit of seven AM and seven FM, which they reached in 1957. They acquired new operations in Chicago, Buffalo, Detroit, San Francisco–Oakland, and Los Angeles. McLendon’s reputation as an unabashed huckster frequently attracted the interest of the FCC, but he never let legalities curtail his experimentation. He started the first all-news format in radio in 1961 by arranging a sales-rights agreement with a station in Tijuana, Mexico, dubbing the station XTRA, and aiming the transmitter toward the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The method was reversed when he purchased KCND-TV in Pembina, North Dakota, and beamed its programming to nearby Winnipeg, Canada. He even operated a pirate radio station on a ship off the coast of Sweden until its pop music format became so popular that Sweden’s parliament passed laws barring him from competing with the government-owned radio.

There were occasional failures, too. KADS in Los Angeles, McLendon’s all-want-ads station, proved to be a short-lived experiment. And many Texans remember Car-Teach, his unsuccessful attempt to sell educational cassette tapes to commuters. Once, even the tried and true mnemonic-call-letters gimmick backfired, when he tried to capitalize on San Antonio’s large military population by changing KTSA’s call letters to KAKI. In spite of an intensive promotional campaign, the station’s ratings dropped until a secretary at the station clued McLendon in on the scatological meaning of the Spanish word caca. The call letters were quickly changed back to KTSA.

Through it all, B. R. McLendon played a significant role. “As a businessman, Gordon was marginal,” explains one of his former executives. Bill Stewart, the man responsible for many of the early programming innovations, put it more bluntly: “You can’t give B. R. enough credit. Gordon never opposed his father. He was a great idea man, but he could piss through money like no one else.”

Bolstered by his father’s careful surveillance and his colleagues’ talent, McLendon found time to dabble in other endeavors as well. Between 1958 and 1960 he produced three made-in-Dallas B-grade movies—a particularly memorable piece of schlock titled The Killer Shrews (in which McLendon had a cameo role in a death scene), The Giant Gila Monster, and the relatively tame My Dog Buddy.

After flirting with film he charged into the political arena, entering the 1964 Democratic senatorial primary against Ralph Yarborough. His timing couldn’t have been worse. It was only months after John Kennedy’s assassination, and right-wing conservatives from Dallas—of whom Gordon was unabashedly one—were still politically taboo. Lyndon Johnson, up for reelection, was adamant on maintaining party unity in Texas and insisted that Democratic leaders throw their support to Yarborough, the liberal incumbent. Still, the primary was one of the most colorful, most heated state contests since W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel won the governorship with the help of the Bible and the Light Crust Doughboys. McLendon capitalized on reports that Yarborough had accepted money from West Texas swindler Billie Sol Estes. The senator fought back, calling his opponent a “hate huckster” and “disc jockey” and wondering aloud how a man who’d already bankrupted a radio network could manage the state. McLendon hit the stump, giving 350 speeches in eighty days and taking along friends like John Wayne and Chill Wills. But an eleventh-hour retraction by a witness to the alleged payoff from Estes sealed the election for Yarborough. Four years later, McLendon threw his hat into the ring again as a Democratic candidate for governor but withdrew shortly after announcing, citing his inability to agree philosophically with President Lyndon Johnson.

McLendon’s obsession with achievement had its darker side as well. Though success brought him a spacious ranch on Lake Dallas that Rolling Stone once described as a “french-fried version of Xanadu,” and though he surrounded himself with Hollywood celebrities, both of his marriages ended in divorce. By the time the McLendon family began selling off its broadcast holdings, he had clearly lost his enthusiasm for the medium; after so many triumphs he seemed bored. What McLendon likes to portray as a reluctant farewell was actually a shrewd display of business sense. The liquidation of KILT in 1969 and KLIF two years later, for instance, couldn’t have been more calculated. At the time, they were the top-rated stations in Houston and Dallas respectively, each pulling in more than 20 per cent of its city’s radio audience. McLendon had not only lost interest but he’d also seen the handwriting on the wall: FM was beginning to come of age and AM was headed for the Edsel bin. FM’s superior signal quality and the increased availability of FM receivers ushered in an era of specialization in radio programming. In the seventies, the acceptance of FM tuners would effectively double the number of stations in most markets, paving the way for ever more sophisticated formats aimed at ever more specific groups of listeners.

By then my tastes had changed, too. I had discovered album rock and put aside my Otis Redding and Paul Revere records in favor of the new, more progressive sounds of Jimi Hendrix and Cream, artists who were not readily available on the local Top 40 stations. Rather than endure the bubble-gum music and screaming chatter of stations like KLIF, I switched to the FM band, where the jocks spoke in whispered tones and played songs back to back without annoying interruptions.

The increased number of available channels brought to a close the days when one station could dominate an area as KLIF had. Whereas KLIF once regularly captured 20 per cent of Dallas’s audience, a mere ten-share presently insures a top position for a station in that city. Radio is making more money than ever: the Dallas–Fort Worth market, which ranks as the nation’s eleventh largest, generates more than $35 million in revenue annually, a fact that more than a few out-of-town investors have taken note of. Today only three of the Metroplex’s 35 stations are locally owned—KSKY-AM, a Christian-oriented station, and WFAA-AM and KZEW-FM, both owned by the Belo Corporation. KLIF has been in a state of gradual decline since the McLendons sold it to New York–based Fairchild Industries in 1971; the once-proud flagship station now commands only a five- or six-share of the audience. Consequently, Fairchild—which paid $10.5 million for the station—unloaded it in December for a mere $4.25 million.

As a condition to the original sale, the McLendons agreed not to operate an AM-band station within 150 miles of KLIF for ten years. No mention was made of FM, however, which in 1971 wasn’t considered serious competition. So with his son, Bart, acting as manager, McLendon dropped the progressive-rock format of KNUS-FM, KLIF’s old sister station, revived a few gimmicks and contests, and went after KLIF’s audience. Three years later, KNUS became the first FM contemporary-music station in the area to beat its AM competitor in the ratings.

Some saw it as Gordon McLendon’s last hurrah. He saw it differently. “I made a terrible mistake,” he protests. “I gave Fairchild an agreement that does not expire until 1981. I signed it, my father signed it, and my son, Bart, signed it. And it hurt because it involved Bart. It keeps him from being a competitor in that market.” In Gordon McLendon’s mind, at least, AM still means bigger profits.

At 32, Bart McLendon is the sole male heir to the McLendon empire. But insiders say he will never be able to follow in his father’s footsteps. “Bart, unfortunately, is the son of a very brilliant guy who’s an unbelievable success in the broadcast business,” says veteran Dallas radio executive John Butler. “He tried to emulate his father, but his father was inimitable.”

To those of us who miss his broadcast personae, life after radio has looked like just an epilogue for Gordon McLendon. Although he’s still active, failing health has plagued him. He and his Hollywood partner, Sy Weintraub, have invested heavily in movie stock—together they own the third-largest block of shares in Columbia Pictures—and McLendon threatens to produce a full-blown Hollywood epic one of these days, but that project has already been delayed for over a year. The family fortune has increased spectacularly; much of the $100 million the McLendons received for their accumulated broadcast holdings was invested in precious metals when gold cost only $40 an ounce. Yet the family has deliberately retreated from the public eye, to the point that Town and Country magazine overlooked them when it profiled Texas’ richest families last year.

Life in the fast lane had certainly extracted its price, I thought a few months after my first meeting with McLendon, as I watched him slowly make his way down the aisle of an eastbound jet. His face was drawn and his hair combed forward in a futile grasp at lost youth. Associates had once marveled over his ability to do without sleep, to stay up all night to make deals and discuss policy. Now just walking seemed to be a task. Accompanied by his pert, well-tanned girlfriend, he was headed for New York, where he would make his final stop on an informal “Farewell to Radio” tour at the request of a former Milwaukee disc jockey and McLendon employee named Tom Snyder.

Though his broadcasting empire, once the focus for his tremendous energy, no longer existed, McLendon remained very much a driven man, living out of suitcases as he shuttled between residences in Geneva, Stockholm, Liechtenstein, Los Angeles, Palm Springs, and Dallas. Over the previous two weeks, he’d been to nearly all of them—plus London and Singapore—overseeing his family’s investments. After appearing on Snyder’s Tomorrow program, he would go to Acapulco to speak before the National Committee for Monetary Reform. During the two-and-a-half-hour plane ride, he spoke passionately of finance, of balancing the national budget, and of the men he has most admired: the lone eagles, the gamblers, and the risk takers.

“I don’t know if you recall all the criticism that Michelangelo got,” he said at one point. “He was all but persecuted. Another one, right in our own era, is a guy named Bill Veeck [the president of the Chicago White Sox]. He’s been hurt since he’s been in baseball. If we let our imaginations run wild, we can think of a lot of others as well who’ve been persecuted.

“I could never have been part of the establishment because I wouldn’t have been able to do any of these crazy things. It just wasn’t the thing to do. Remember, what I was doing was attacking an establishment, a journalistic and radio establishment set like a grand piano in concrete. So I had to be an iconoclast.” But McLendon’s battles were largely behind him, and he appeared to be glad that his work was done.

I skipped the studio taping when we got to New York. Perhaps it would be better to take my last look at Gordon McLendon on the tube, I thought. He has never projected well on the television screen, but in the wee hours of that summer morning he seemed a reborn man. His eyes were bright and brimming with life. His shoulders were thrown back as he sat erect and confident. He played to the cameras with seasoned finesse and ease, holding his own with Snyder, furrowing his brow even more intently than his student, and waving his arms more forcefully to drive his points home. But as reassuring as the image was, something still wasn’t quite right. So I simply closed my eyes and listened as he reeled off a string of anecdotes about the golden days of sportscasting with Dizzy Dean and about the selling of Top 40 radio. Slowly, right before my ears, the familiar voice once again grew larger than the man could ever be. Right there on national television, in front of an audience of millions of insomniacs, Gordon McLendon became as big as the Colossus of Rhodes, one foot planted firmly in Dallas and the other hooked up to some mysterious electrical impulse that connected him to the rest of the world. And though I knew he didn’t really exist anymore, the greatest showman in radio played on my imagination one more time.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas