Taxidermy is kinda like baseball. Some kids, no matter how much they practice, are never gonna be worth a damn. Other kids pick it up pretty quick, and they’re just gonna be good at it. I had my first deer mounted when I was eleven years old, and seeing all the animals on the walls of the taxidermist’s shop fascinated me. So when I got my driver’s license and my dad said I could either find a job or spend another summer building fences on our ranch, I opened up a phone book and started calling around to taxidermists to see if anyone needed any help.

I found a guy nearby and basically became his grunt. I’d skin and flesh the animals—take all the meat off them—and then cape them out. The cape is the actual hide that goes on the mount, and I’d get the cape ready by salting the underside of the hide and turning the lips and ears inside out and salting those too. And that’s what I did for the duration of the summer.

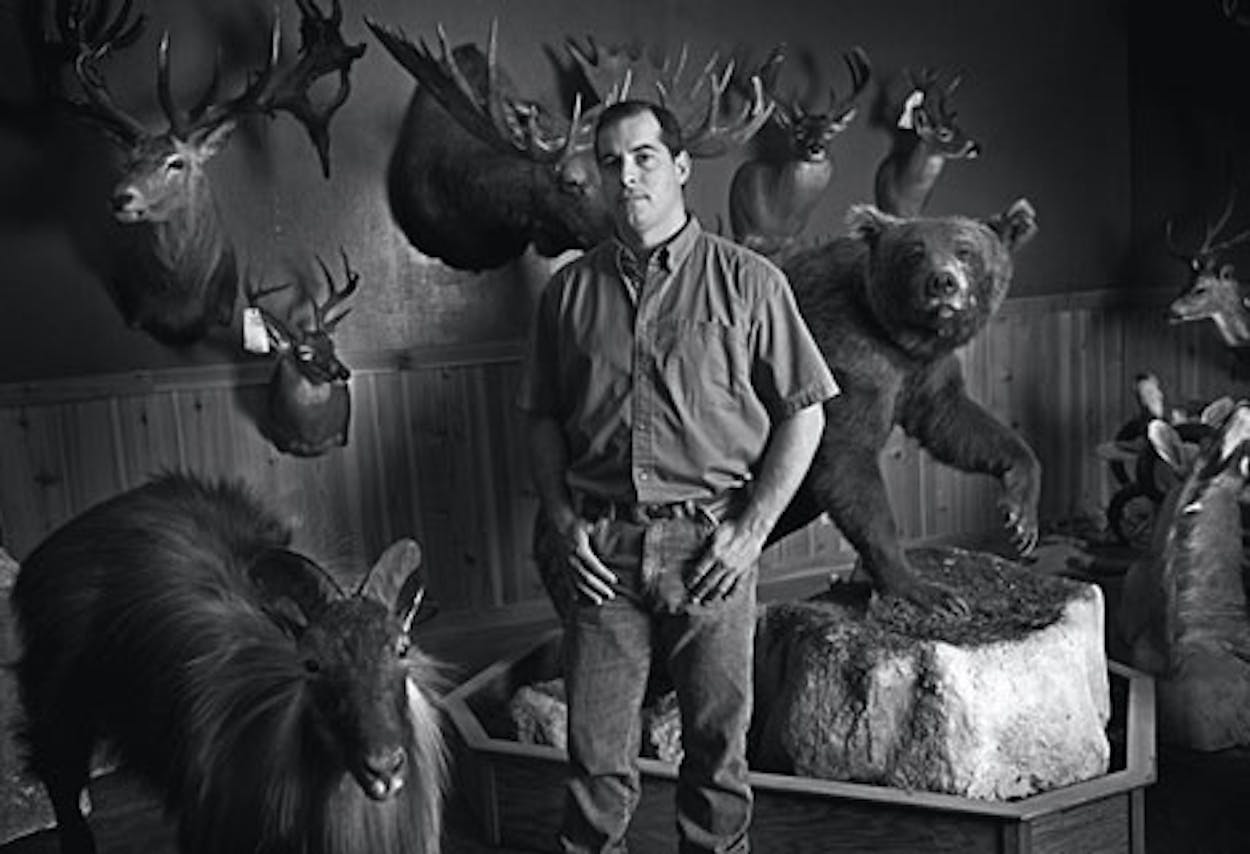

When August rolled around, the football coach called and said practice was starting in two weeks. That’s when I told my mom and dad that I didn’t want to play sports anymore, because I was going to be a taxidermist. My dad threw his hands up and said, “No, absolutely not.” Luckily for me, my mom said, “This is what he wants to do.” So I worked apprenticeships in the area for four more years, and then, when I was 21, I got a bank loan and opened up my own place. If it weren’t for my mom, I probably never would’ve done that. But at the same time, it was an absolutely crazy thing to say at 16 years old, that this is what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

When an animal comes in, we take three measurements, one from the tip of the nose to the corner of one eye and two from two different places on its neck. We cape it and send the hide to a tannery, store the horns, and order a form—a Styrofoam model of the animal’s head—that’s a similar size. Then, when the cape and form come in, we reproduce what the hide tells us. We soak the cape in water so it’s pliable, so it will stretch. We do clay work on the form, making alterations to get it to the exact same size as the animal’s head. Then we’ll take a file and create some muscle structure and veins in the face, giving it the kind of detail it had when it was alive; set the eyes in clay and screw the horns on; glue the cape on, nail it in place, and let it dry for two weeks. When we’re ready to finish it, we pull all the nails, smooth out the nose, clean out the nostrils and tear ducts and mouth, and go over it with an airbrush, just like painting a car in a body shop.

Those steps will be done in that order no matter who’s doing the job. But how it’s done makes all the difference. You gotta have experience and artistic ability, but most of all you have to know what the animal looks like in real life. That’s why hunting and taxidermy go hand in hand. You can look up animals in books or on Google for reference points, but if someone spends six or seven thousand dollars to go to New Zealand and shoot a Himalayan tahr, they want a taxidermist who knows what a Himalayan tahr is.

With an animal like a tahr, you won’t do it justice if you don’t mount the whole thing, because it’s their hair that makes them so attractive; their horns aren’t that impressive. Plus, the hunter wants to remember the hunt. Tahr live in some rough country, and when you’re hunting them, you’ll see them jump from rock to rock and in one minute run up the side of a mountain that’d take you two hours to get up. I’ve got two tahr in my shop now, and the guy who sent them specifically wanted them coming down a hill and looking to the left, because that’s the way he saw them in the field.

I’ve got customers all over the U.S., and they hunt all over the world like that. They call before they go on their hunt and say, “I’m going to Africa, and I plan on shooting fifteen animals,” and we’ll print them all the shipping tags they need to get the animals through the USDA. I’ve got a client over there right now who just called and said he was hoping to send me an elephant. I’ve done hippos before, and moose, which are even bigger. But nothing as big as an elephant. He said he was going to shoot it with a bow. We’ll see how that goes.

One client, he likes to hunt leopards. And he shoots zebras for the bait. But he hates to not do anything with the zebras, so he has them mounted. Only this time he already had a bunch of ’em and had already given one to his son, so he’s like, “Think of something different to do with these two.” I was like, “Well, we could do a floor pedestal with ’em, and I could put one coming off the other one’s shoulder, kind of like they’re standing side by side.” And he’s like, “Well, it sounds neat. I think we’ll do that.” He hasn’t seen it yet, but I have another customer of mine who goes to Africa all the time and he saw it and now he wants to shoot two zebras and do the same thing.

But my bread and butter is still white-tailed deer. During deer season last year, we did three hundred mounts, most of them whitetails. Plus, we did 2,500 deer through our meat-processing business—sausage, jerky, salami, buck sticks, you name it. We had fifteen guys working in here and were open seven days a week. If there’s a frustrating part of this business, it’s that my personal hunting is drastically reduced. I always have to be back here by Sunday noon during deer season.

You know, my grandfather lived just down the road, and when he was still alive, he’d go into town to check his mail and then come up here and sit and talk and watch me work. I remember him saying one day, after about my third year here, once I was doing pretty well, “I never told you this, but I always felt sorry for you, opening up this taxidermy shop out in the middle of nowhere. But you made me realize it doesn’t matter where you’re at. If you do a good job, people are going to bring stuff to you.”

And yeah, so he sat here for three years thinking that, and finally, after he figured I was doing all right, he tells me, “I always felt sorry for you.” Thanks a lot, Grandpa.