This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The goal sounded like the ultimate high-tech fantasy: Figure out a way to make a computer that was faster and more powerful, less expensive, more efficient, and—most important—compatible with a family of computers ranging from laptops to mainframes, all able to run the same software. To Russell Stanphill of Motorola and other designers of personal-computer microprocessor chips (the postage stamp-size piece of circuitry that is a computer’s brain), the idea wasn’t farfetched: The technology had been around since the late seventies. A single powerful PC chip could be designed to do all this—but there was a formidable obstacle to developing it. The major microprocessor manufacturer in the world—California-based Intel—dominated 80 percent of the market. No single computer-chip company had the money or the power to take on the industry Goliath.

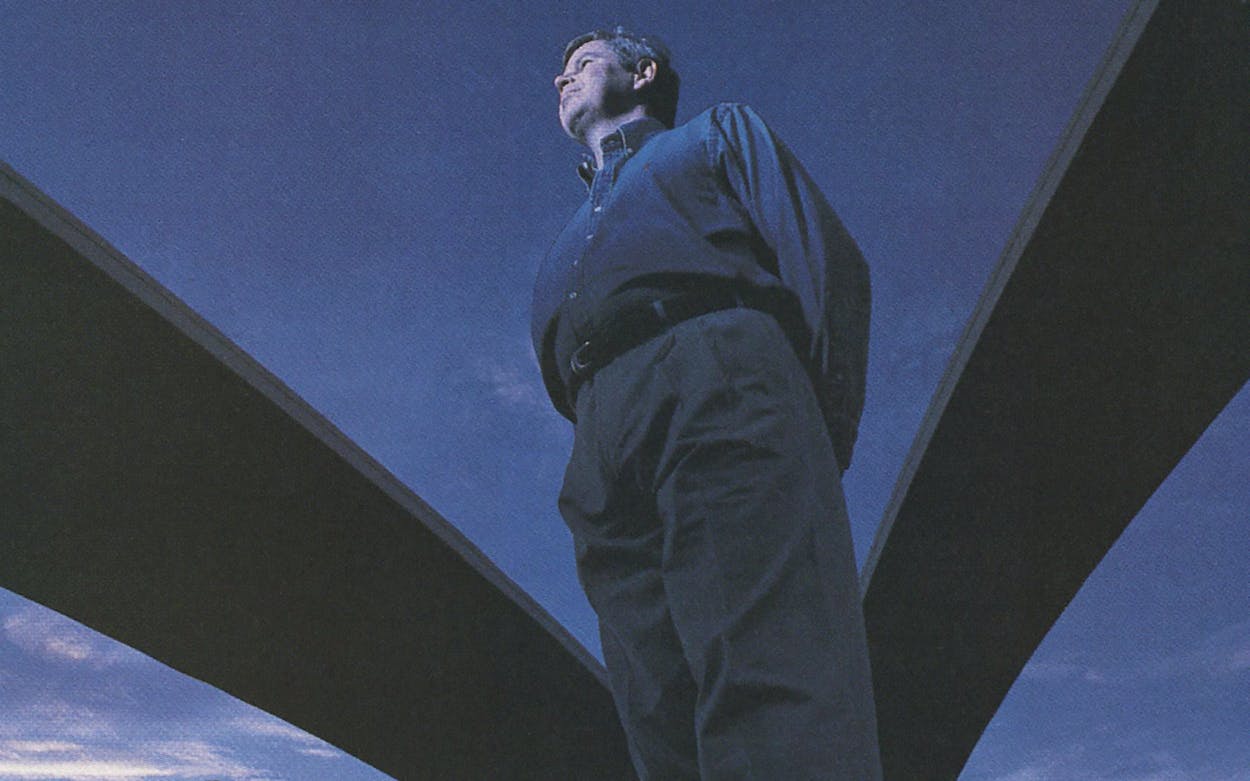

But what if a group of computer companies banded together to take on Intel? An unlikely idea in the intensely cutthroat computer business—but that’s what happened. Motorola and one of its best customers, IBM, figured that by teaming up with Apple, Motorola’s other best customer, they could bust Intel’s virtual monopoly. It was a daring scheme, particularly for Apple and IBM, both of which have faltered in the marketplace in recent years. “Everybody in the industry laughed about the possibility of a partnership,” says Stanphill, who in 1991 was picked to head the development team for the PowerPC (as it was dubbed). “We worked out a deal—sometimes with as many as a hundred lawyers involved at a time—in three months,” he says. The demands of leadership were a change for the highly competitive “techie.” Stanphill set to work on the basics: finding a building in Austin and designing the space to accommodate 350 designers and 550 computers. With Tom Whiteside, his counterpart at IBM, and his apple counterpart, Paul Nixon, Stanphill recruited the best designers from all over the world. Enthusiastic employees named the collaboration Somerset, after the British county where King Arthur conferred with his knights about such matters as finding the Holy Grail.

In the past year Somerset has introduced three PowerPC chips; a fourth is on the way. “This is the most important development in the computer industry in our generation,” Stanphill says. And apparently Intel thinks so too. Although the company initially scoffed at the PowerPC as empty promises, it is now rushing to launch the next generation of its best-selling Pentium chip. Because the power chips are being produced on schedule and on budget (another industry standard-breaker), Stanphill can afford to spend some time away from his microprocessor and more time on another of his passions—sand volleyball. In anticipation of the extra hours Somerset designers would devote to the PowerPC chip, Stanphill included a volleyball court in his specifications for the 86,000-square-foot Somerset building. Looking out over the sunny atrium to the sandy court, Stanphill admits, “I could live here.” If he decides to, he will have even more time to focus on inventing even better PowerPC chips—and on winning over more of Intel’s customers.

- More About:

- TM Classics