“IT WAS A MISTAKE,” NOLAN RYAN TOLD ME later about the pitch he had thrown to Round Rock mayor Charlie Culpepper, but I didn’t believe him. Ryan had come to the Austin suburb to celebrate the groundbreaking for the stadium where the as-yet-unborn Round Rock Express will play baseball starting in the spring of 2000. The Express is a Ryan family business—Nolan is the majority owner of the Texas League franchise, and his 27-year-old son, Reid, will serve as president—and their field of dreams, appropriately, will rise out of what was until recently a cornfield.

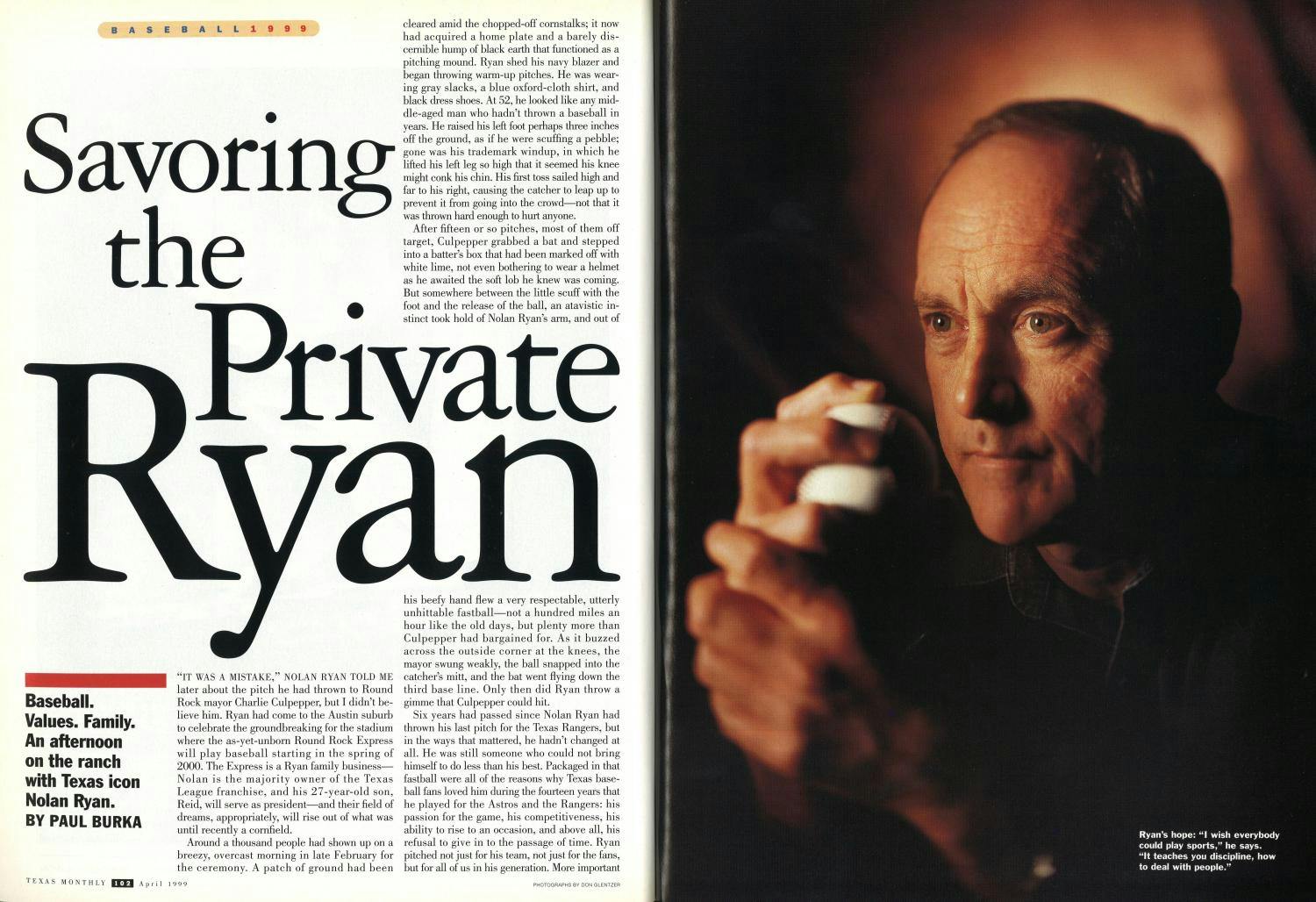

Around a thousand people had shown up on a breezy, overcast morning in late February for the ceremony. A patch of ground had been cleared amid the chopped-off cornstalks; it now had acquired a home plate and a barely discernible hump of black earth that functioned as a pitching mound. Ryan shed his navy blazer and began throwing warm-up pitches. He was wearing gray slacks, a blue oxford-cloth shirt, and black dress shoes. At 52, he looked like any middle-aged man who hadn’t thrown a baseball in years. He raised his left foot perhaps three inches off the ground, as if he were scuffing a pebble; gone was his trademark windup, in which he lifted his left leg so high that it seemed his knee might conk his chin. His first toss sailed high and far to his right, causing the catcher to leap up to prevent it from going into the crowd—not that it was thrown hard enough to hurt anyone.

After fifteen or so pitches, most of them off target, Culpepper grabbed a bat and stepped into a batter’s box that had been marked off with white lime, not even bothering to wear a helmet as he awaited the soft lob he knew was coming. But somewhere between the little scuff with the foot and the release of the ball, an atavistic instinct took hold of Nolan Ryan’s arm, and out of his beefy hand flew a very respectable, utterly unhittable fastball—not a hundred miles an hour like the old days, but plenty more than Culpepper had bargained for. As it buzzed across the outside corner at the knees, the mayor swung weakly, the ball snapped into the catcher’s mitt, and the bat went flying down the third base line. Only then did Ryan throw a gimme that Culpepper could hit.

Six years had passed since Nolan Ryan had thrown his last pitch for the Texas Rangers, but in the ways that mattered, he hadn’t changed at all. He was still someone who could not bring himself to do less than his best. Packaged in that fastball were all of the reasons why Texas baseball fans loved him during the fourteen years that he played for the Astros and the Rangers: his passion for the game, his competitiveness, his ability to rise to an occasion, and above all, his refusal to give in to the passage of time. Ryan pitched not just for his team, not just for the fans, but for all of us in his generation. More important than the milestone achievements of three hundred wins and five thousand strikeouts and seven no-hitters that he reached with the Rangers was the time in 1993 when Robin Ventura of the Chicago White Sox, twenty years his junior, charged the mound after being hit by a pitch. Ryan, then 46 and a month from retirement, dropped his glove and administered a swift pugilistic lesson in respect for one’s elders. Way to go, Nolan. Win one for the geezers.

Ryan holds 53 records, more than anyone else in major league history, and he will be inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame this summer, but he will always be remembered as much for the kind of person he was as for the kind of player he was. He grew up in Alvin and still lives there. He married his high school sweetheart and is still married to her. The Sporting News once wrote that he held the record for giving the most free autographs of any professional athlete in any sport. His work ethic, which enabled him to fend off advancing age with a rigorous exercise routine, kept him performing at a superstar level longer than anyone in the history of baseball. Somewhere toward the end of his 27-year career, he came to be perceived by the public as not just a great ballplayer but also a great human being. That is the difference between being a celebrity and being an icon, and Nolan Ryan is the rare hero who has made it across the line.

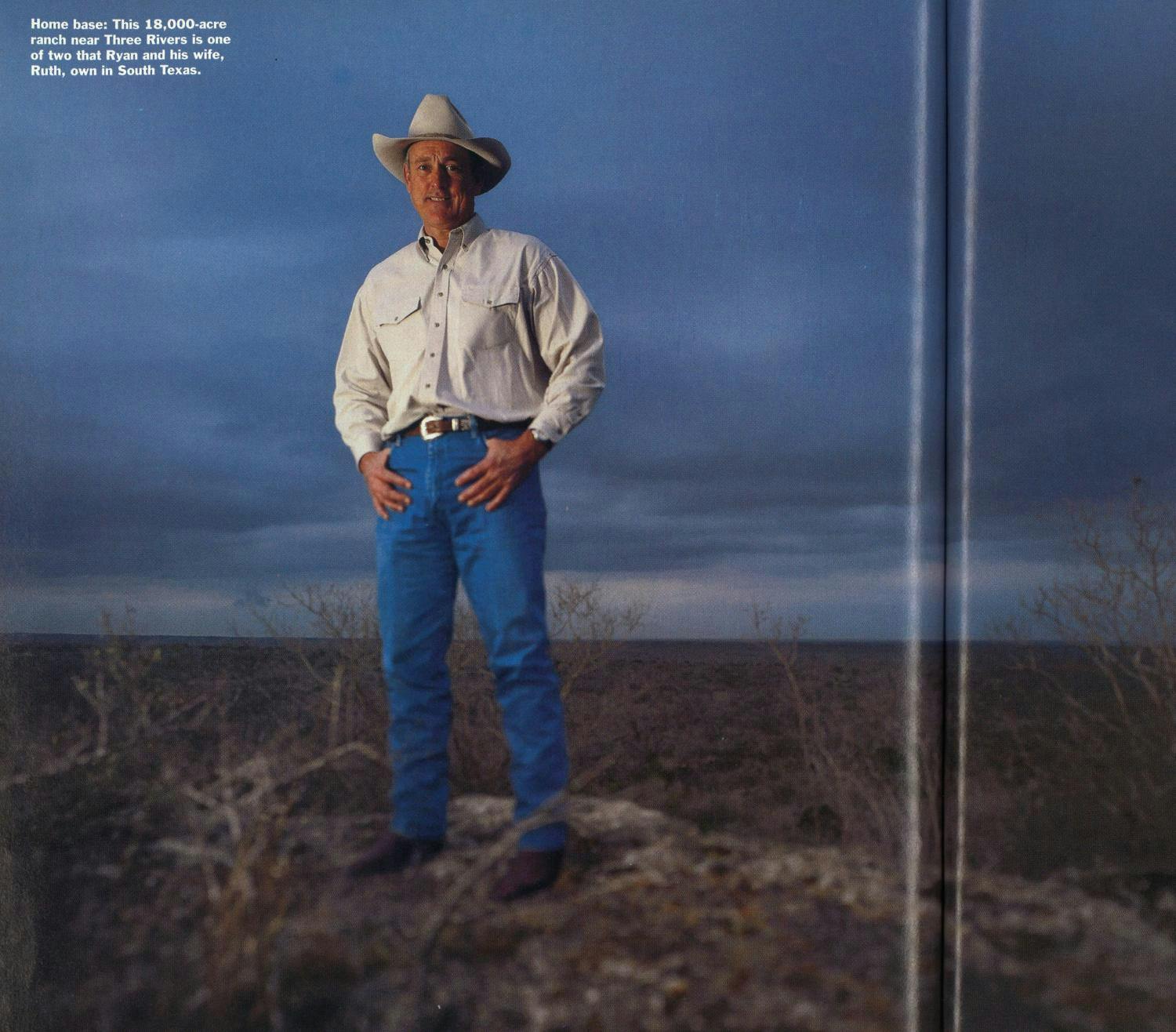

HEROES SEEM TO BE IN SHORT SUPPLY these days, and not just in sports. So the occasion of Ryan’s election to the Hall of Fame, which was announced in January, afforded the perfect opportunity to check in with him. He and his wife, Ruth, were spending a few days on one of the two ranches they own in South Texas. This one covers around 18,000 acres—28 square miles—of hard-core brush country near Three Rivers. It’s accessible only by a couple of unmapped roads scraped out of yellow dirt so stubborn that it sticks to your car even after a rain. From the ranch gate, which bears Nolan’s N-R brand, it’s another two miles to the one-story limestone house, which sits atop a rise that’s the second-highest point on the property, an island in a sea of brush that runs undisturbed to the horizon on all sides. The only features visible are a life-size bronze in the front yard of a cowboy driving Longhorns, a collection of sheds a couple hundred yards to the north, and in the distant southwest, a single mesa.

Ruth Ryan met me at the door with the firmest handshake I have ever received from a woman and led me into the living room, a large, comfortable gathering place whose decor was aggressively Texan. The chandelier, greater in diameter than a wagon wheel, was constructed of interlocking antlers. Six mounted trophy bucks looked down from various positions around the room. Lights mounted along the walls were concealed in metal sconces bearing lone-star patterns. More lone stars, some bluebonnets, and a waving Texas flag were etched into the glass in the front door. Additional Texas motifs graced the custom fireplace screen, including arrowheads and a state seal. Above the fireplace was a G. Harvey painting. At the other end of the elongated room sat a jukebox containing C&W records by just about anyone you might want to hear, from George Strait to Steve Wariner to Conway Twitty.

Nolan Ryan is an old-time Texan, and his values are those of old-time Texas: the ways of the open range and the oil patch and the real Texas Rangers, whose story, chronicled by historian Walter Prescott Webb, is told in one of the many books about Texas Ryan keeps in a tall, stand-alone bookcase with glass doors near the fireplace. Be sure you’re right, then go ahead. I shall never surrender or retreat. One riot, one Ranger. A man who gives his handshake gives his word. Dance with who brung ya. Don’t get to thinking you’re better than other folks. Come and take it, Robin Ventura. Maybe the old Texas wasn’t really like that, but as myth it’s not such a bad creed to live by, especially when compared with the meddling morality of today’s suburbia or the greed of modern athletes. It is no accident that the appreciation for Nolan Ryan the man began to rival the appreciation for Nolan Ryan the pitcher only after he left the California Angels in 1980 to come home to Texas—first to pitch for the Astros, then for the Rangers. Texans recognized him as one of their own.

Ryan loves Texas. For the first half-hour that I was at his ranch, we talked about nothing else. “I like to get out and drive,” he said. “This state is so diverse. We have four ecosystems here. You can’t find that in any other state.” He talked about hiking in Big Bend Ranch State Park and driving on dirt roads through the Chinati Mountains, south of Marfa, where, on one trip, a Border Patrol car suddenly materialized out of the vast emptiness and followed him all the way into town. He spoke fondly of Gonzales, where his other ranch is (“Did you know that the town was set up according to a Mexican land grant?”), and about why South Texas lacks the town squares with imposing courthouses that are common elsewhere in the state (“This part of Texas developed late. The towns grew up along the railroad tracks”).

He had fitted himself into a corner of a couch, looking solidly built and fit in his jeans, Western shirt, and boots. But his right leg stuck straight out across the cushions at an awkward angle. “The knee bothers me all the time,” he said. “I’m looking at a knee replacement. The cartilage is all gone.” It’s the price he has to pay for a hundred thousand or so pitches that began with all his weight on the leg.

I asked Ryan about the name on his ranch gate that surrounds the N-R brand: Ray Ranch. The N-R stood both for Nolan Ryan and Nolan and Ruth, but who was Ray? “The Ray family founded the ranch,” Ryan said. “It’s a well-known ranch in South Texas. J. Frank Dobie wrote about it in Tales of Old-Time Texas. You know, he grew up not far from here and spent a lot of time at his uncle’s place. He would come over here to see a friend named Rocky Reagan, who leased the ranch from an estate in St. Louis.”

Later, I looked up the story of the Ray Ranch, which Ryan bought in 1991. “Many an old ranch house by its very looks calls up human destinies,” Dobie’s tale begins. In 1868 Jim Ray and his brother headed west from Alabama to start a ranch in Texas. A business associate of their father’s named Hess, upon learning that the boys would be carrying $5,000 each, headed for Texas first, struck up a friendship with a band of Comanche, and lay in wait for the brothers. The Indians and Hess ambushed them in the back country and killed Jim’s brother, but he escaped across a creek. Later he discovered that Hess had drowned in the swift waters and recovered his brother’s money belt from the body. Still in peril in isolated country, he built a makeshift raft and floated down the Nueces toward civilization. At a sharp bend the raft hit the bank and broke apart; Ray had to cling to a root to keep from being swept away. Finally he swung free and made his way up the bank to get the lay of the land. “He thought he had never seen a more beautiful sweep of country,” recounted Dobie, “than the land in and beyond that bend of the Nueces.”

In a way, Ryan’s twentieth-century odyssey paralleled Jim Ray’s. Both were just eighteen years old when they left home to seek their destiny. Both faced long odds against making it. Both survived a lot longer than anyone else in their circumstances would have done.

OTHER GAMES HAD TO BE INVENTED, but baseball springs from the nature of man—the impulse, common to all infants, to hurl an object at a high velocity in a purposeful direction. Of all the people who have inhabited the earth, none has hurled a certain round object a little over two inches in diameter at a greater velocity than Nolan Ryan: The speed of his fastball was once timed by Rockwell International at 100.9 miles per hour.

For most of his career, however, there was considerable dispute about how good a pitcher he was. He never won a Cy Young Award, and he won as many as twenty games only twice, in 1973 and 1974, his second and third years with the Angels. The former season was his best. Among the standards by which a pitcher is judged are whether he gives up fewer hits than innings pitched and amasses more strikeouts than innings pitched; in 326 innings, Ryan gave up only 238 hits while striking out 383 batters (one of his records). On top of that, he threw two no-hitters before the All-Star break; nevertheless, the American League manager in the All-Star Game didn’t choose him for the team (Ryan was added by order of the commissioner of baseball), and Jim Palmer of the Baltimore Orioles edged him out for the Cy Young Award. Ryan remembers Palmer’s comment after the voting, and it still rankles: “He said, ‘Nolan Ryan went for strikeouts. I went for outs.’ But we were different kinds of pitchers. I couldn’t be the kind of pitcher Jim Palmer was. I was a strikeout-style pitcher.”

He was that kind of pitcher when the New York Mets signed him out of Alvin High School in 1965, a six-foot, two-inch, 140-pound string bean, for $20,000 and $500 per month. He was the youngest of six children, the son of an oil-production worker whose work ethic he inherited. Lynn Ryan had a second job, delivering the Houston Post on a 55-mile route, and night after night, Nolan got up at one in the morning to help roll and deliver newspapers before returning home at five to catch two more hours of sleep. He used his signing money to pay off his parents’ mortgage and buy himself a new Impala. He was already dating Ruth, who was just sixteen and two grades behind him in high school. In his second year in the minors he was overpowering—17 wins, just 2 losses, 272 strikeouts—and the Mets called him up late in the season. But his career almost ended before it got started.

The Mets had gotten him to join an Army reserve unit so that he wouldn’t be drafted, and when he finished six months of active duty in 1967, he injured his arm trying to get it in shape. “My arm popped like a rubber band,” he told me. “There was no sports medicine then. They just sent me home to rest it. I thought my career was over.” The Mets wanted him to have surgery, but he refused. Either his arm would heal or he would go to vet school at Texas A&M, as he had always planned to do. He and Ruth had gotten married in June, and he wasn’t going to struggle in the minor leagues with a bum arm; his pay had been so low that he had had to pump gas and do pickup jobs in the off-season.

Fortunately, the arm healed. Ryan made the team in 1968, but his frustrations continued. Because he had to leave every other weekend and for two weeks each summer to fulfill his military obligation, he couldn’t get into a regular pattern of pitching every four or five days. “I needed innings,” Ryan said. “Pitching is like golf; it’s all timing. The way you practice is repetition, repetition, repetition. You want to build up muscle memory. If your delivery isn’t the same, then your control is off. If you’re off an inch up here”—he raised his arm over his head—“then you’ll be off even more when the ball gets to the plate. The release point should always be the same. Once I found my release point, if I missed with a pitch, I knew why I had missed.” I asked him to show me his release point. He raised his arm, then dropped it back down. “I could not put my arm in the position it gets during delivery,” he said. “It only goes that way when I throw.”

His career with the Mets was mediocre, though he pitched in the 1969 World Series as a reliever and earned a save. (It was the only World Series he would ever play in.) After a lackluster 1971 season—10 wins, 14 losses, and almost as many walks as strikeouts—he was ready to hang ’em up. In her 1995 book, Covering Home: My Life With Nolan Ryan, Ruth relates that while they were driving back to Texas after the season, Nolan said to her, “Either they trade me or I’m quitting baseball.” They traded him to California. In the next three years he pitched more than 900 innings, struck out more than 1,000 batters, and won 62 games for a team with a puny offense. By 1976 he was making $125,000, enough to acquire the eighty acres outside of Alvin that is his main residence today. The next year his salary rose to $300,000. Still, he was regarded as a fearsome pitcher but not a great one. In her book Ruth mentions the two criticisms of her husband at the time: He lost about as many games as he won, and if you kept the score close, you’d beat him. After the 1979 season, he became a free agent, and the Astros brought him home as the first million-dollar ballplayer.

“I thought I’d retire as an Astro,” Ryan said. He turned 33 in 1980, an age by which power pitchers usually have begun to fade. Who could have foreseen that his career, then totaling thirteen years, was less than half over? Over the next nine seasons with the Astros, he broke Sandy Koufax’s record of four no-hitters, led the league in earned run average twice, and at the age of 40, initiated a run of four consecutive years in which he topped his league in strikeouts. But the last two years of the streak would take place in Arlington, not Houston. Ryan’s contract expired in 1988, and the new contract the Astros offered him called for a 20 percent salary reduction. Both California and Texas sought to sign him, and Ryan chose the Rangers because they were closer to home, even though Angels owner Gene Autry offered more money than the Rangers’ $1.6 million.

“I was going to play one more year,” he said, “and I realized, ‘Hey, I’m enjoying this so much, I’m going to play as long as I can.’” Who wasn’t enjoying it was American League hitters. Ryan struck out 301 of them in 1989 at the age of 42. No pitcher older than 31 had ever accumulated 300 strikeouts in a season. Two years later, he gave up only 102 hits in 173 innings, the third-stingiest ratio of all time, just over 5 hits per game. Who holds the record? Nolan Ryan in 1972.

By this time, all doubts about Ryan’s greatness as a pitcher had been extinguished. He had outlasted the skeptics; there was nothing to compare him with. When he pitched his seventh no-hitter in 1991 at age 44, the New York Times called him “John Wayne with a baseball cap.” Kelly Gruber of the Toronto Blue Jays, the team victimized by Ryan’s no-hitter, told the Boston Globe, “I hate to lose, but my respect and feelings for Nolan Ryan are so great that I’m actually happy to have been there. That may be the wrong feeling, I don’t know, but he’s more than a marvel. He’s the model for what we all should be. When I’m not facing him, I’m always rooting for him. It’s the same with a lot of players. [I]f we had to lose this game, I’m glad he got the no-hitter, and I’m glad I got to see it. He’s a great man.”

OUTSIDE THE RYAN LIVING ROOM, A dark sky was closing in. A photographer showed up early for a shoot and said that he wanted to get started in case it rained. “It never rains here,” Ryan replied, pursing his lips to effect an air of resignation with a dash of rancher’s cynicism. This was one of the few times his expression changed during our visit; Ryan is a man who has spent a lifetime controlling his body, and his face has not been allowed to go undisciplined. He got up to change his shirt, and I went into the kitchen to talk to Ruth. From the size of the refrigerator, it was apparent that the Ryans did a lot of entertaining here. The front had the square-footage of a king-size mattress.

A former cheerleader and state champion tennis player in high school who wears her streaked hair in a ponytail, Ruth Ryan is as perky and outgoing as Nolan is restrained. (When he’s angry, she wrote in her memoir, “He clams up and won’t talk.”) She led me into the dining room, where a round table made of pine with a built-in lazy Susan was surrounded by eight chairs covered in cowhide, and talked about the house. “Nolan designed it,” she said. “He said that his dream house had the bedrooms inaccessible from the rest of the house. You have to go outside to get to them.” We walked out of the kitchen onto a spacious stone patio and saw the bedroom wing, with three doors in a row, each of which led to a room containing multiple queen-size beds. It sounds like a motel, but in fact it’s more like a bunkhouse with a little privacy, which was no doubt what Ryan had intended.

I wondered what it’s like to watch your husband play baseball for a living. It is such a cruel game. The best hitters make outs 70 percent of the time, and the best pitchers are lucky to win half of their starts. Along with the record for the most strikeouts, Nolan Ryan also holds the record for giving up the most walks. Ruth attended most of the home games her husband pitched while he was in Texas, driving to the Astrodome when he was with the Astros and flying up to Arlington for the night when he was with the Rangers. “Some of the wives could enjoy the game,” she said, “but being a pitcher’s wife is different. I died with every pitch. One day after Nolan had retired we went to a game, and I thought, ‘Hey, this is really fun. Relaxing, eating hot dogs, talking to everybody—no wonder people watch baseball games.’ There are things about being a pitcher’s wife I don’t miss at all.”

We caught up with Nolan at the sheds, a group of metal buildings that includes a stable and a shelter for tractors and other ranching machinery and climbed into his pickup for a drive to a setting requested by the photographer: a rocky outcropping called Half Moon Ridge that is close to the Nueces. He stopped the truck on the primitive road, and we had to pick our way through heavy brush for about a hundred yards to reach the outcropping. The first bluebonnets of the season had come out, and Nolan stopped to admire them. “If we could get a good two-inch rain, this country would explode,” he said. Ruth looked at the sky and said something hopeful. Nolan shook his head: “It never rains here.” (He was right; the storm passed to the north.) “The drought of ’96 almost did us in,” he said. “It was a triple whammy: no rain, low cattle prices, high feed prices. At least feed isn’t so bad now.” Close to the outcropping, the brush thickened, and we had to improvise a circuitous route. “Watch out for this one,” Ryan said, indicating a thorny bush that looked like a relative of a pencil cactus. “We call it a jump cactus, because it’ll jump right out and gitcha.”

The photographer began setting up his equipment, and I knew that the conversation was coming to an end. “Are you enjoying retirement?” I asked. Oops, wrong question. For a moment Ryan fixed me with a pitcher’s stare, a look so deep that it seemed to originate from behind his eyeballs, and I noticed that where most people have horizontal lines across their forehead, he has two deep vertical lines above his nose, sculpted by 27 years of scowling at batters and focusing on hitting a tiny target from sixty feet away. Then the stare was gone. “I didn’t retire,” he said. “I just don’t play baseball. One thing I’m short of is time.” Aside from his ranches and the Round Rock Express, he owns a bank in Alvin; he set up the Nolan Ryan Foundation, which will open an exhibit at Alvin Community College this spring; and he serves on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, to which he was appointed by his old friend Governor George W. Bush.

He still does some work for the Rangers too. “They bring their top rookie prospects to Arlington in February,” he said, “and I’ve spoken to them the last few years. Everybody has a weakness, I tell them. Every level you go up in baseball, it magnifies your weakness. I always went to spring training in the best shape I could be, so I could work on my weakness. I’ll never forget what a scout told me one time: ‘You watch kids playing ball, and they’ll tell you what they do best. If they’re fast, they’ll run wind sprints. If they’re fastball hitters, they’ll hit fastballs in the batting cage. You never see ’em working on their weaknesses.’ I wish everybody could play sports. It teaches you discipline, how to deal with people, how to deal with adversity, how to deal with success. You learn the rewards of preparation and the value of dedication and sacrifice.”

And then he tugged his white Resistol lower on his forehead and climbed up on the rock to be photographed, silhouetted against the capricious clouds and the sunlight that was trying to break through.