One afternoon in October 2016, Peter Hotez holed up in his office at Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine, where he is the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine. Surrounded by obscure science volumes and honors bestowed by dignitaries ranging from Bill Clinton to Greg Abbott, he meticulously set about injecting himself into a battle that most scientists had been careful to avoid. Hotez had spent his career fighting deadly diseases in far-flung corners of the world, but now he began tapping out an essay called “Texas and Its Measles Epidemics” for the scientific journal PLOS Medicine. The modest title belied just how provocative the article would turn out to be.

In it, he recalled the measles outbreaks that had routinely devastated the U.S. before the introduction of a vaccine, in the sixties. The virus killed 6,000 Americans a year in the early twentieth century, and thousands more suffered permanent hearing loss and neurological damage. Globally, it killed millions. Thanks to vaccine campaigns, that number had dipped to under 100,000 by 2013. In the U.S., it was declared eliminated in 2000. Yet as Hotez considered more-recent statistics, he wondered, “Could large-scale measles outbreaks and deaths return to the US?”

He was particularly concerned about Texas. Days earlier, he had been fielding routine emails when a disturbing set of data popped up on his screen: the number of Texas children who had been granted exemptions from school vaccine laws for “reasons of conscience” had increased steadily, year by year, from around 3,000 in 2003 to just under 45,000 in 2015. Until this point, Hotez had watched the state’s anti-vaccine lobby with increasing dread but little urgency. Now a sense of alarm came over him. He was staring at a measles epidemic in the making.

Measles remains one of the most contagious viruses on earth. Studies have shown that populations that dip below 95 percent vaccine coverage become a tinderbox. Hotez noted in his essay that counties in West Texas and the Panhandle were approaching that threshold, and vaccine exemption rates in many Austin-area private schools had already exceeded 20 percent (one had even surpassed 40 percent). “I predict measles outbreaks in Texas could happen as early as the winter or spring of 2018,” he wrote.

He feared that the anti-vaccine movement was growing more powerful. Advocates of “vaccine choice,” as they prefer to frame their efforts, have become increasingly confrontational in the past decade. In protests, they’ve marched with posters showing syringe-wielding government agents stopping cars and forcefully injecting wailing babies. They are skilled social media combatants, often referring to public health advocates as “Nazis” and the “medical police state.” Some have launched Twitter and Facebook campaigns to try to discredit doctors who publicly promote vaccines. Paul Offit, the director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has long been the most outspoken critic of the anti-vaccine movement, and he sometimes requires security during public speeches because of death threats made against him and his children. After journalist Amy Wallace wrote a profile of Offit in 2009 for Wired magazine, she received dozens of threatening letters, including one that warned, “This article will haunt you for a long time.” Barbara Loe Fisher, the president of the National Vaccine Information Center, which claims to be dedicated to the prevention of “vaccine injuries and deaths,” sued both Wallace and Offit for libel. (In the article, Offit said of Fisher, “She lies.”) The case was dismissed, but a lawsuit—or the threat of one—remains a potent weapon in the vaccine war.

And yet, in his PLOS Medicine article, Hotez not only criticized the anti-vaccine movement, he singled out some of its most influential players. He pointed to Texans for Vaccine Choice, a Keller-based political action committee that formed in 2015 and already carries powerful sway over state lawmakers. He also condemned Andrew Wakefield, a British former gastroenterologist (his medical license was revoked by the General Medical Council of the UK in 2010) who now makes his home in Austin. In 1998, in the journal The Lancet, Wakefield alleged a link between vaccines and autism. The Lancet later retracted the paper, and based on several studies published over the past decade, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has concluded that there is no connection between the two. Wakefield became a pariah in the scientific community, but he remains a hero to many in the anti-vaccine movement.

Those who know Hotez as a friendly academic roaming the halls of the Texas Medical Center, the sprawling Houston complex that contains Baylor and Texas Children’s Hospital, where Hotez is also on staff, weren’t surprised he chose to enlist in the battle. “He’s always been fearless,” said longtime friend and colleague Mark Kline. Hotez has spent three decades developing vaccines for some of the world’s most pernicious diseases—infections with hard-to-pronounce names that affect people in countries most Americans are unlikely to visit. Treating these diseases is often considered a lost cause, but he’s fought relentlessly to cure them anyway. (In 2005, he and two colleagues helped coin the phrase “neglected tropical diseases,” a category that is now recognized by the World Health Organization.) And although vaccine scientists often become troll targets, Hotez’s work had up till now been too remote—too far afield from the interests or cares of most Americans—to cause much fuss. “I got a pass,” he said.

“The current activities in Texas and Washington DC could ignite reversals of global disease elimination and eradication efforts that are now more than 50 years in the making.”

Then he published the forceful essay in PLOS Medicine. And he was only just getting started. In February, he wrote a candid op-ed in the New York Times: “Today, parents in Texas have to live in fear that something as simple as a trip to the mall or the library could expose their babies to measles and that a broader outbreak could occur.” In March, in Scientific American, he explained, “We need to recognize that the current activities in Texas and Washington DC could ignite reversals of global disease elimination and eradication efforts that are now more than 50 years in the making.” In April, during an anti-vaccine demonstration at the state capitol, he went totally unfiltered on Twitter: “Austin #antivaxx rally: People actually eager to endanger lives of #Texas children just to espouse their miserable pse[u]doscience ideologies.”

Needless to say, he no longer gets a pass. One blogger has predicted that Hotez will top the list of “the bonehead roll-call of history.” Another labeled him the “latest vaccine pitchman, clueless on vaccine-autism science.” He’s frequently harassed on Twitter: “YR PUSHING POISON AND DEATH BY SYRINGE.” When he ended his Scientific American article by arguing that the movement posed such a threat to children that “we need to take steps now to snuff it out,” social media erupted in indignation. In one Facebook post, a Texas group told Hotez to “go back into the hole you crawled out of.” The co-founder of Generation Rescue, a nonprofit for which Jenny McCarthy is the president and celebrity spokesperson, dubbed him the “heir apparent of Paul Offit.” (“He’s welcome to the position,” Offit joked when I called him this fall.)

Yet there is one considerable detail that separates Hotez from Offit. Hotez has a 25-year-old daughter, Rachel, with autism. And for Hotez’s critics, nothing is off-limits: “How much are these people paying you? Holy shit. You’re a complete idiot. Your own daughter has autism and you sit there and try to convince people that vaccines don’t have a link to autism. What, are you trying to make other people suffer so you can feel better about yourself? You fucking idiot. You have no morals whatsoever, and you know you’re a fucking liar. I hope you rot in hell.”

“That,” Hotez said, “was a great email to wake up to.”

Hotez doesn’t mind being in the limelight. In fact, he considers it an essential part of his mission as a scientist. He attributes the rising tide of vaccine resistance—and of anti-scientific sentiment in general—in part to a public that isn’t familiar with research processes or the actual researchers behind them. He points to a survey from Research!America in which 70 percent of the participants couldn’t name a living scientist, and those who could were largely limited to Stephen Hawking, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Bill Nye the Science Guy (who was actually an engineer before he became everyone’s favorite nerd). So when reporters call to ask about scary infections, Hotez answers. On camera, he’s an expert straight from central casting, with his wire-rimmed glasses and disheveled hair, which he doesn’t bother to comb, even for national television. On a good day, he’s shaven.

In 2014, shortly after a man walked into a Dallas emergency room with Ebola virus, Hotez made an appearance on Comedy Central’s The Daily Show. In a segment on the national hysteria, host Jon Stewart ridiculed the fear-stoking graphics and we’re-all-going-to-die! facial expressions of news anchors. The piece included a young, attractive doctor trying to tamp down public fear. “What do you know? You’re not a scientist!” Stewart hollers. “Scientists have crazy hair and mustaches and wear glasses and lab coats! And they’re so busy and absentminded, they’ll just put any old tie on! Could be a bow tie, for all I know. Find me one of those guys!” He then cuts to a video clip of Hotez, whose red-and-blue bow tie is peeking out from his starched lab coat. The audience roars.

Hotez is keenly aware that researchers whose celebrity exceeds their scientific output are not viewed favorably in academia.

Unlike the caricature of a bumbling scientist, Hotez doesn’t shroud his opinions in dense jargon. When the Zika virus began to spread across Latin America last year, Hotez predicted, both in news reports and in congressional testimony in March, that the virus’s transmission in Texas was inevitable. “If I were a pregnant woman living on the Gulf Coast or in Florida, in an impoverished neighborhood in a city like Houston, New Orleans, Miami, Biloxi, Miss., or Mobile, Ala., I would be nervous right now,” he wrote in the New York Times. The first case appeared in Texas months later, and local news outlets anointed him Houston’s Zika expert. In the weeks after Hurricane Harvey, he was interviewed almost daily about the microbes hidden in the muddy water or the likelihood of a mosquito apocalypse.

Hotez is keenly aware that researchers whose celebrity exceeds their scientific output are not viewed favorably in academia. (One journal refers to this degree of fame as the Kardashian Index.) Yet he also believes that silence can lead to catastrophe. “There’s a general rise in what I call anti-science in America, and it’s manifested in a number of different ways, like in climate change denial or saying that vaccines cause autism,” Hotez told me. “The media is partly responsible because they entertain these outlandish theories and they create kind of a false equivalency between that and what the scientists have to say. Journalists will often talk about the ‘vaccine controversy’ around autism. There’s no controversy. The science is clear: vaccines don’t cause autism. And yet [journalists] continually leave the door open.”

Still, few talk show hosts or reporters have time for the topic Hotez is most eager to talk about: the diseases affecting “the poorest of the poor,” to use one of his favorite phrases. Americans are much more intent on hearing about diseases like Ebola than less-headline-worthy germs that pose a threat to millions more in the world’s most overlooked places (never mind that climate change will likely bring more of these germs to our shores, Hotez has warned). “When I talk about these diseases in the U.S.,” he said, “the lights go out.” Yet it was those diseases that built his career and brought him to Houston.

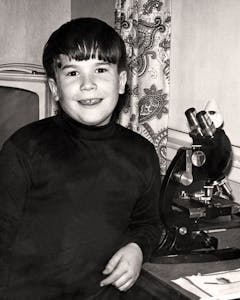

Hotez, now 59, grew up the third of four children in the suburbs of Hartford, Connecticut. His father worked at United Technologies and taught business administration at a local community college; his mother stayed home with the kids. In grade school, Hotez asked his parents for a microscope. Not a toy, a real one. The first time he looked into the eyepiece and spotted a paramecium swimming by, all of its cilia rippling, he was awestruck that a dropper of creek water could contain an invisible universe. As the years went by, his room became a cluttered repository of glass microscope slides, science tomes, and the anti-establishment rock and roll vinyl of the sixties: Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones, the Who.

When his bedroom started to smell too much like pond scum, his parents insisted he move his makeshift laboratory to the basement. In junior high, he saved up the $1-per-week allowance he received from his grandfather and ordered a preserved frog from the Carolina Biological Supply catalog. Mostly, though, he sent away for microscopic specimens that would arrive in small glass jars. As a teenager, he relished textbooks. “In the West Hartford Public Library, I remember seeing my first parasitology book,” he told me. “Years later, I went back to the library, and the book was still on the shelf. I don’t think anyone’s checked it out since.”

He also developed a fascination with geography. He would leaf through giant atlases that his parents kept in the living room and trace the outlines of continents on sheets of paper. Like the worlds he discovered beneath his microscope, they seemed like mystical realms waiting to be explored. “I think parasitic disease was the perfect combination of the two,” he said, “because these were diseases of far-off places.”

He graduated from Yale University in 1980 and went on to New York City, where he obtained an M.D./Ph.D. from Cornell University and the Rockefeller University. As he was nearing completion of the seven-year program, he happened to scan the personal ads in the back of New York magazine, the eighties equivalent of Match.com. One of them stopped him. “It was the only one that didn’t say she was looking for someone tall,” said Hotez, who is five feet four. He composed a letter, confessing that he was a workaholic because “I truly love what I do.” The recipient, now his wife, Ann, worked in advertising at People magazine. They married the next year, in 1987.

The couple moved to Boston for Hotez’s pediatric residency at Massachusetts General Hospital. He had no interest in private practice, instead wanting to be a physician-scientist who prevented infections in forgotten corners of the planet. He returned to Yale as a postdoctoral fellow, and over the next decade he rose to the rank of associate professor and launched his own lab. After that, his work attracted such attention that people started building labs specifically for him. In 2000 he was named head of the newly created Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University. Then, in 2011, after he visited Houston to deliver a lecture, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital were so taken with him that they brokered a deal to create the National School of Tropical Medicine and the Center for Vaccine Development, respectively. Hotez was put at the helm of both, and a dozen lab personnel moved with him.

Mark Kline, the physician in chief of Texas Children’s, credits Hotez with not only bringing new science to the forefront of his field but making a mark on the culture of the Texas Medical Center. Like others I interviewed, he can’t ever recall seeing Hotez in a bad mood; wherever he goes, he leaves a wake of optimism. “If he were the average M.D./Ph.D. who trained at all those top-notch institutions, he’d have a modest contribution at best to what’s going on around here,” Kline said. “But the fact of the matter is, he’s one of the nicest people on the planet.”

Over Hotez’s thirty-year career, he’s helped develop vaccines and treatments for some of the worst afflictions of extreme poverty. The job has taken him to many of the countries he first discovered in his parents’ atlases, and he’s learned to adapt to the unexpected. (Once, while working in rural China, he learned that everyone, including visiting Western scientists, was expected to sing and dance at the local karaoke hall. He did both, badly.) Most of the illnesses he studies flourish in pockets where a warm climate converges with unsanitary conditions. Hookworms, for example, are found in raw sewage and commonly enter the body through hands and bare feet before making their way to the gut.

In 2008 he had published a report that focused on common parasitic infections in the United States and concluded that poverty, not climate, was the thread common to all of them.

Soon after moving to Houston, though, his perspective on neglected tropical diseases was radically altered. One day he took a wrong turn into a poor neighborhood just a few miles from the hospital where he worked, and as he passed dilapidated houses with torn window screens, trash-strewn gutters, and stray dogs, he was struck by how similar it felt to the squalor he’d seen while working in Asia and Latin America. He had already begun to theorize that so-called tropical infections had more to do with economics than weather. People with meager wages live in homes more easily invaded by pests, in neighborhoods with poor infrastructure and illegal dumps. (Old tires, notorious for being mosquito farms, aren’t allowed to accumulate in high-end zip codes.) In 2008 he had published a report that focused on common parasitic infections in the United States and concluded that poverty, not climate, was the thread common to all of them. It was the first time he had expanded his perspective on global health to include his own country.

As Hotez continued his research over the next few years, he began to draw deeper connections between infection and income inequality, and in 2016 he published Blue Marble Health. The book argues that humanity’s most neglected infections actually thrive in the world’s largest economies—not among the poorest of the poor but the poorest of the rich. Hotez estimates that 12 million people in the U.S. are living with an unrecognized tropical disease. Some are the most startling conditions you’ve never heard of: take toxocariasis, an illness caused by a parasitic worm carried by stray dogs (in addition to cats and foxes), who often congregate in alarming numbers throughout low-income neighborhoods. (In South Dallas, the feral dog problem has grown dire enough to generate newspaper editorials and complaints to city council members.) The worm’s eggs infest the soil through dog feces and cling to the hands of children as they play outside. Once swallowed, the parasite works its way into the brain, where it can impede neural development. In 2008 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a study in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene estimating that 21 percent of African Americans and 12 percent of whites under age six had been exposed to the parasite. Those living in households with the lowest education levels were the most likely to be infected.

To Hotez’s ire, the study was largely ignored. “This is a worm that’s been shown to migrate through the brain and cause developmental delays,” he said. “The question is, what’s the contribution of this neglected tropical disease to the education gap among socioeconomically disadvantaged children?” He went on, his speech quickening. “You know how many grants the federal government gives for toxocariasis? That’s right, zero, although we tried. We think we now have a new diagnostic kit that we can develop for it, but do you know what they focus on? How many grants are they giving for Ebola?” I looked it up: Ebola, 200-plus. Toxocariasis, 0. In September, acting on an invitation from an environmental activist, Hotez and Baylor tropical medicine scientist Rojelio Mejia made worldwide headlines after confirming the presence of hookworm infections in rural Lowndes County, Alabama. The parasite, which is typically spread when people defecate outside, was thought to be eradicated in the U.S., but they found that about a third of the population they studied had been exposed. A reporter for the Guardian, Ed Pilkington, visited one community and found raw sewage piped out just a few yards from people’s homes, collecting in an open pool: “A closer look revealed that it was actually moving, its human effluence heaving and churning with thousands of worms.” Residents told Pilkington that they were afraid to ask for help because a decade earlier the state had arrested people for not having proper treatment systems. An elderly woman had been jailed for failing to install a septic tank, which would have cost more than her annual income. A walk through Hotez’s department at Baylor becomes a lesson in a multitude of tropical diseases that are becoming disturbingly Texan. Kristy Murray, an assistant dean, recently helped document the reappearance of typhus, a bacterial infection (notorious in the Middle Ages) that’s transmitted through flea bites, lice, and chiggers and can cause fever, headache, rash, even death. It was once on the brink of elimination here, but between 2003 and 2013, Texas health authorities reported 1,762 cases. It began mostly in the south, but its range has expanded from 9 counties to 41. Hotez uses the cameras and microphones in his orbit to try to illuminate these kinds of maladies. “I’ve always been drawn to doing things where, if I weren’t there to do it, maybe nobody else would be doing it. And Peter’s that way,” Kline, his colleague, told me. “I think that he’s been drawn to what he does in part because he wanted to make a real difference and impact a field where there weren’t just droves of professionals already.” For Hotez, that now includes battling the impending measles outbreak in his own backyard. Hotez’s willingness to speak out against the anti-vaccine movement is so uncommon that his name is now used to gin up interest in protests. That was the case this September, when dozens assembled on a muggy Monday morning at a hotel just outside Houston’s Inner Loop to condemn a global vaccine summit taking place inside. The activists were energized by the arrival of the Vaxxed Nation Tour bus, which for the past year had traveled the country to promote Vaxxed, a conspiracy-laden film directed by Andrew Wakefield. Sheila Ealey, the protest’s organizer, appears in the movie. She’s also the co-founder of the Texas Medical Freedom Alliance, which was hosting a conference of its own near Rice University. Hotez, however, was unfazed. “SCARY in addition [to] #Vaxxed tour coming to #Houston Sept 18-19 they’re holding all-star #antivax summit. Wear garlic,” he tweeted. Although opposition to vaccines isn’t new, Texas has recently become a key battleground for the movement. Earlier this year, the Washington Post reported that within state-based efforts to oppose vaccination requirements, “Texas is among the most organized and politically active.” The movement is one of the few remaining causes that isn’t partisan. On the West Coast, it usually finds a home in the political left—“It’s peace, love, granola, ‘we have to watch out what we’re putting into our kids,’ ” Hotez said—but in Texas, it mostly settles in the right, where the arguments largely revolve around freedom. “These vaccines are for the poorest of the poor,” he said. “I will never make any money on these, and no one else will either.” Texans for Vaccine Choice, for example, explains in a blog post that its “goals are that parents call the shots and that we must have informed consent.” The Texas Medical Freedom Alliance makes the same argument: the government can’t tell us what to do with our kids. To which Hotez says, “Well, of course they can tell you what to do with your kids. We do it all the time. If you’re a parent, you’re obligated to strap your kid into a seat belt or a car seat, right? It’s not an option. It’s just the law.” But unlike car seats, vaccines don’t just protect your own children. They also protect babies too young to be immunized, people who can’t take vaccines for legitimate medical reasons, and those whose immunity has waned with age. Still, the movement’s fragmented ideology makes it incredibly difficult to contain, and the number of Texas schoolchildren exempted from vaccines continues to grow. From 2015 to 2016, that figure jumped from under 45,000 to almost 53,000, meaning the threat of a measles outbreak has only intensified. In October the journal JAMA Pediatrics published a guide to help doctors talk to parents about immunization “when a significant proportion of the US population is impervious to scientific facts.” Meanwhile, the most popular line of attack against Hotez is that he is in cahoots with pharmaceutical companies, conspiring to get rich off of vaccines. In one of the rare instances where he directly rebuked his adversaries, he demanded the retraction of a blog post accusing him of being a profiteer. “I’m making Chagas and schistosomiasis vaccines. These are for the poorest of the poor,” he said. “I will never make any money on these vaccines, and no one else will either.” Hotez rarely engages his critics directly because he says it would be like playing a game of intellectual Whac-A-Mole, but he regularly contributes op-eds to the Houston Chronicle, including one in September that called for Texans to “stop the self-inflicted wounds and rein in the antivaccine lobby.” And he’s got a new book coming out, scheduled for release in 2018, with the working title “Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism.” Hotez has talked about Rachel, his daughter, from time to time, but this will be by far the most personal thing he’s written. He relied on both Rachel and his wife, Ann, for input as he was writing. Some thirty years after he first wrote Ann and confessed that he was a workaholic, he’s turned this, one of his most important efforts, into a family project of sorts. Hotez never hesitated to make Rachel a central part of the book, but he has prepared for the reactions he knows will come. He consulted with a few biomedical ethicists, who reassured him, and one even volunteered to write a foreword for the book. “The anti-vaxxers will pull all the stops to say anything hurtful that they can,” Hotez said. “The one piece that does get to me is if they say I’m being exploitative with Rachel. I do worry about it.” Even Offit, who’s been the target of some of the most extreme attacks, recognizes that the same vitriol leveled against him cuts even deeper for Hotez. “The notion that you would attack a father of a child with autism who clearly understands your issues better than anyone—what he goes through is in many ways infinitely worse than what I go through, because I don’t have that other emotional burden.” One morning this fall, as Houston was drying out from Hurricane Harvey, I met Hotez for coffee at his Montrose-area home. His phone was already abuzz with calls from journalists wanting to know what horrific post-hurricane diseases might arise. As we sat down at the dining room table, I glanced up and saw Rachel, who has lush, auburn hair and piercing brown eyes, descending the stairs. She spotted a plate of pastries. “Can I have one?” she asked her dad, speaking in quick staccato. “You have to say hello first,” Hotez answered. “Hello. Can I have one?” Hotez nodded, and I asked her what she wanted people to know about her dad. “That vaccines don’t cause autism,” she replied. “Dad, can I have another piece?” He smiled. “You just said that so I’d give you another piece of the éclair.” Rachel is the third of Hotez’s four children. She was a colicky infant, unlike her older siblings, who were three and four at the time. Ann noticed other differences too: Rachel had an unusually high-pitched cry, and when Ann would pick her up to comfort her, her tiny body would remain stiff rather than nestling into her mother’s arms. At the time, Hotez was working long hours as a fellow at Yale, and Ann attributed what she was seeing in Rachel to the fact that she was exhausted and perhaps had less time with her youngest child. But when Rachel was eighteen months old, her pediatrician referred her for a developmental evaluation, and just before her second birthday she was given a diagnosis of “pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified,” a catchall for what would now be considered autism. Two decades ago, autism had barely entered the public lexicon and was rarely associated with girls. It is because of Rachel, not in spite of her, that Hotez felt compelled to speak publicly about vaccines in the first place. Now Rachel spends her time running errands—Subway, the bakery, H-E-B—which her mother divvies up to occupy her days. Well-meaning acquaintances occasionally remark that someone like her shouldn’t be walking the streets of Houston by herself. “That’s really hard to hear,” Ann said. “There’s always a worry in the back of our minds, but it’s better than having her sitting watching TV all day. She wants to be out in the world.” What Rachel really wants is a job. “My siblings have jobs, and I want a job too,” she told me. She’d like to work in a bakery. She also wouldn’t mind being a zookeeper. But mostly she wants to be independent, and her options are few. Ann has struggled to navigate the limited resources available to help adults in Rachel’s situation find work. When I asked Hotez about Rachel’s lack of opportunities, he conceded, in a rare display of irritation, “I’m a little bit angry.” He believes the outcry over vaccination has hijacked meaningful conversations about autism. “Not only are they putting kids in danger, it’s doing something else. It’s taking the oxygen out of an initiative to support kids with autism.” Resources are especially scarce as they grow older, he explained. “We’re totally on our own. There’s so few special services available for adults with autism, and why is that? I blame partly the anti-vaccine guys. Anytime autism is discussed at a high level, it’s all about vaccines. Nobody focuses on what kids really need. I think that organizations like Texans for Vaccine Choice are actually hurting families with autism.” When I called Jackie Schlegel, the executive director of Texans for Vaccine Choice, she told me that autism is “irrelevant to our organization, to be honest.” The group is not anti-vaccine, she said, just pro–informed consent, and no one has a problem with Hotez promoting immunization. “What’s concerning to me is when we ask any individual to fully trust in a system without question.” But Hotez isn’t discouraging questions. He understands the shock and helplessness parents feel when something debilitating happens to their child. Any explanation, even a misguided one, offers some comfort. He also understands why parents would naturally question whether something needs to be injected into their healthy babies. Despite the deluge of incendiary posts and tweets lobbed in his direction, he’s sympathetic to parents desperate for answers, and hearing that autism likely begins as genetic glitches, before birth, isn’t always satisfying, he said. In fact, it is because of Rachel, not in spite of her, that Hotez felt compelled to speak publicly about vaccines in the first place. “I’m out there as someone with a child—now an adult—with autism, and I can articulate why vaccines are not causing autism.” Still, Hotez’s fear of a measles outbreak in Texas hasn’t waned. When he initially predicted the possibility of an epidemic, he pointed to the winter and spring of 2018 as the first potential threat. As we sat at his dining room table, those months were rapidly approaching. The last time vaccine protection fell sharply across the U.S., in the late eighties, measles swept the country and infected more than 4,400 Texans; 12 died, including adults in their twenties, toddlers, and a boy who likely caught the infection from his mother. Rachel is hopeful that the upcoming book will make a difference. It’s her way of contributing to the discussion in a way that only she can, and it allows her to be more like her brothers and sisters, who are pursuing lives of their own making. “She wants to get her voice heard,” Hotez said. As we talked further, Rachel became increasingly restless. It was time for her to walk to Subway. “She has a very rigid schedule,” Hotez explained gently. I nodded and thanked Rachel for the conversation. Her money counted out, she gathered her bag and a floppy sun hat and turned back to me. “Make sure that you get your kids vaccinated, okay?” Then she opened the front door and stepped into the sunlight.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Peter Hotez