This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

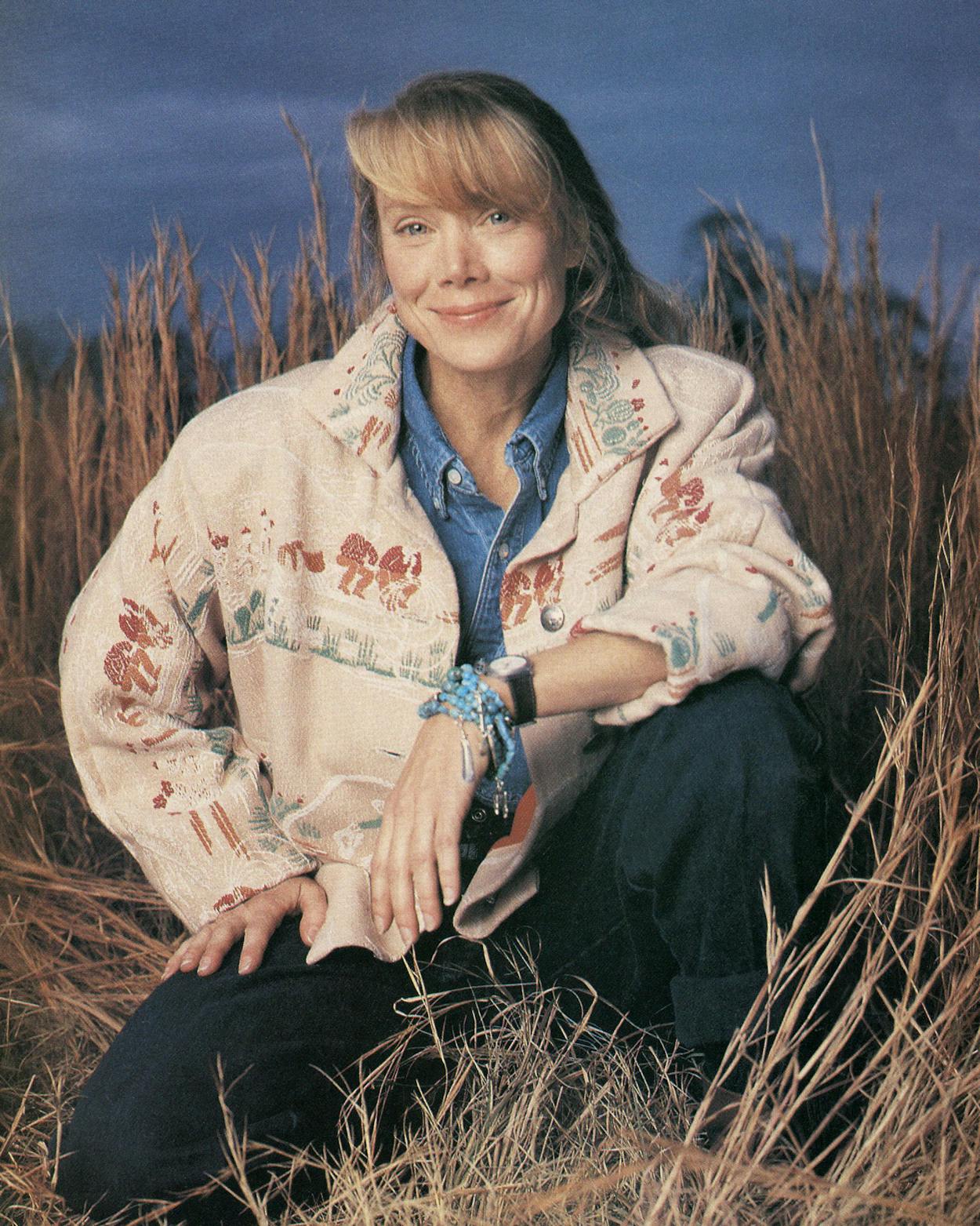

C’mon in,” says Sissy Spacek. “I want you to meet my tribe.” Sissy is standing in the doorway of her suite at the Four Seasons Hotel in Austin, where she and her family are staying while she is working on a romantic comedy called Hard Promises with William L. Petersen. She looks immaculately casual, dressed in an unpressed denim shirt, a pair of blue-jean cutoffs, and tasseled loafers stuffed with bulky white cotton socks. Her thick strawberry-blond hair is pulled back in a loose ponytail, and her proud face—the wide jaw, the cool blue eyes, the petite nose, the pale and freckled skin—is scrubbed clean. She isn’t wearing a dab of makeup. Yet she has such poise and self-confidence that it would be impossible not to realize that she’s somebody special, even if you didn’t know that she is a small-town East Texas girl who has made herself into an Academy Award–winning movie star.

Her turquoise charm bracelet jingles loudly as she bends down and scoops up the youngest member of her family, Madison, a chunky, dark-haired two-year-old girl. Madison hasn’t had a nap and is rolling around on the carpet, crying for her mother. “Madison and I slept nose-to-nose last night,” says Sissy. “Both of us are pretty grumpy.”

“This is my husband, Jack Fisk,” she says. The man seated on the couch is bearded, with dark features like Madison’s, but he’s quieter, shaggier, and infinitely more content. A Hollywood director, he looks properly ethereal and self-contained, like the subject of an Edward Hopper painting. Beside him sits their eight-year-old daughter, Schuyler, whose face, long and framed by her bright yellow hair, is the picture of misery: Her roller blades and skateboard are packed away, and she is doomed to an afternoon of boredom in the hotel room. “It’ll be okay, Schuyler,” coaxes her father, sweetly. “We’ll find something fun to do. I promise.”

The hotel room is cluttered with children’s books, toys, and clothes. Next to the window is a table piled high with the leftovers of a room-service lunch—a half-eaten cheeseburger, a bowl of soup, several glasses of apple juice. This family knows how to make itself at home on the road. While Sissy has been in Austin making Hard Promises, Jack has been in Houston directing a cable-TV movie about the life of Earl Rodgers, a famous Los Angeles criminal attorney who defended Clarence Darrow. “Sissy and I both like working in Texas,” says Jack. “It’s home for Sissy. Somehow we can handle more chaos here.”

Sissy and Madison are wrestling on the floor when suddenly a familiar stink hits Sissy in the face. “Jack,” she wails, “Madison’s got a dirty diaper.” Sissy and Jack have been married for sixteen years, long enough to communicate in gestures and cryptic phrases. This time the message is, It’s your turn. Jack lifts himself off the couch to take charge of their children while Sissy raises her arm to give me the high sign. “Let’s get out of here,” she says, with a shimmer of exuberance. “We can talk in the bar.”

I’ve been a Sissy Spacek fan since 1974, when I saw her in Badlands. Sissy plays an empty-headed teenager who is so bored by her hometown that she leaves to join Martin Sheen on a murder spree. I grew up in a small town in East Texas and could identify with wanting to escape. I knew that Sissy understood that longing, for she first left Quitman, a town of less than two thousand people halfway between Dallas and the Louisiana border, when she was seventeen. Sissy narrated Badlands, and her voice—low, twangy, so peculiar to our place and time—reminded me of home. She sounded like everybody I ever grew up with. Besides, I liked seeing her name on the movie credits. You don’t get any more authentically Texan than being a boy named Bubba or a girl named Sissy.

Some actresses succeed because they capture the glamour of Hollywood. But Sissy succeeds because she isn’t seduced by it. Acting is her job, and she works hard at it, but her family is her life. Whether she’s on-screen or off, she is still a country girl at heart. She is at her best portraying people like herself—ordinary people who wind up living extraordinary lives. In 1981 she won an Oscar for her portrayal of Loretta Lynn in Coal Miner’s Daughter. When I asked Tommy Lee Jones, her costar in that film and another Texan, what makes Sissy special, he thought for a long time and finally said, “Sissy is always Sissy.”

Her story is not one of those Hollywood magical moments of early discovery and instant stardom but of hard work and attention to details. In eighteen years, she has made seventeen movies. She has gone from playing pathetic teenagers such as the title character in Carrie to complex grown-up women such as Nita in Raggedy Man, and in the process she has joined Meryl Streep and Jessica Lange at the top of her profession. She has been nominated for an Academy Award five times. On the set, Sissy is absorbed with the technical side of the business, overpreparing for her parts, insisting on more rehearsals. The more elusive and complex the technical problem, the more fun she has. Sometimes her obsession with details can create conflicts with other actors. During the shooting of The Long Walk Home, her current film about the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, Sissy insisted on knowing where every coffee cup would be placed in every scene, while her costar, Whoopi Goldberg, demanded spontaneity. “It was like mixing oil and water,” says Richard Pearce, the director, “but the mix works.”

But a major reason for her success is that Sissy has resolved the dilemma that faces every Texan of ambition: Whether to stay here and remain part of the culture, or rebel and leave. Sissy found a third alternative—she left, but she took her roots with her. “I never made the decision to leave home,” she tells me. “I was just going forward. Besides, home was always there when I needed it.”

I’ll have the biggest glass of sparkling water you’ve got,” Sissy tells the waitress in the bar of the Four Seasons. Back when she was in high school in Quitman, she ate a cheeseburger and an order of fries and drank a large Coke every day of the week. The price of fame is that she now guzzles bottled water and eats steamed vegetables. We take our glasses outside and settle at a table, facing the lush banks of the Colorado River.

“Boy, do I love Austin,” says Sissy, curling up in a chair and wrapping her arms around her legs. “Jack teases me because I always sigh with relief when we cross the state line into Texas. I feel so safe here.” Joggers pass by, none of them recognizing her. This moment of anonymity relaxes her. She tosses a baggy green sweater onto the nearest chair and swigs her water like a thirsty boy. Catching me staring, she explains, “I used to play softball every summer back in Quitman. My two brothers demanded I be tough. There were certain girls they wouldn’t let me invite over because they were too feminine and fragile.”

It’s late in the afternoon, and the wind off Town Lake rips right through us. People who know her well told me that Sissy is shy in groups—not the kind of star who looks forward to being seen at Spago’s in Hollywood or doing the Johnny Carson show—but one on one she’s extremely animated, even hyper. As she talks, her hands fly through the air and words tumble out of her mouth like horses headed for the barn.

“I’m real close to the source here,” she says. “I tell my friends who live other places that people in Texas have a lot of bottom.” The source that has shaped her is the habits, rhythms, and values she grew up with in Quitman. As it is for most of us, her sense of home is never as strong as when she has returned after a long absence.

East Texas still has a hold on her. Instead of living in Beverly Hills or Bel Air or Malibu, she has chosen a rural setting that is about as far from Hollywood as you can get, geographically and spiritually. She and Jack live on a 210-acre horse farm in Albemarle County, Virginia. Except for the three or four months a year when she is working on a film, she is, by Hollywood standards, a recluse. “The countryside around our farm reminds me very much of the hills and pines around Quitman,” she says. “Around here no one treats me like a movie star. A lot of famous people have lived there, starting with Thomas Jefferson. There, I’m just Schuyler and Madison’s mom. That’s the way I like it.”

She wants to ground her daughters to their place, the same way that her parents made her a part of rural life in East Texas. She named them both for towns in Virginia. Since Schuyler was born eight years ago, Sissy has centered her life on motherhood and the farm. “Nothing in life prepared me for the way I felt about being a mother,” she says. “Until then, I sort of felt like a blank sheet of paper. I was always trying to second-guess myself, to be what others wanted me to be. The moment I saw Schuyler, I no longer questioned who I was. I knew I was a mother, and everything was going to be all right.”

On a typical day, Sissy wakes up early, goes for a four-mile run through the countryside, comes back to her century-old farmhouse, and shares a cup of coffee with Jack on the back porch. Once Schuyler goes to school, Sissy tends to her garden or makes bread, wrapping her family and environment around her like a warm blanket. After lunch, she puts Madison down for a nap, and then she goes to her office in the house to read scripts or she and Jack go for a ride on their horses or “do something real fun, like go to the dump.”

She met Jack in 1972 on the set of Badlands. He was the art director for the movie. “Jack had built this incredible treehouse on a river,” Sissy tells me. “One day he asked me to ride home with him on a boat. We loaded up, and there came a terrible flash flood. The boat sank. Right then I knew life with Jack was going to be eventful.”

From the beginning they joked that their children would look like Howdy Doody. Jack is tall (six foot two and a half), and Sissy is short (five foot two and a half). She is light with freckles, and he is dark with a wide space between his teeth. Fate didn’t give them a composite child, but one of each. Schuyler looks like her, and Madison looks like Jack.

The reclusive life on the farm suits Sissy’s temperament. She works only a few months a year, and the public aspects of her job—interviews, photo shoots, and autograph seekers—drain her energy. She loves center stage, but only when she’s pretending to be somebody else. When she and Jack decided to get married in 1974, she couldn’t even face walking down the aisle of the Methodist church in Quitman. Instead, they drove to a small chapel in Santa Monica, California, to be married in private. They both wore jeans, and their only witness was Jack’s Hungarian sheepdog—named Five—which signed the wedding license with its paw print.

The best actors, says The Long Walk Home director Richard Pearce, protect their inner mystery. “Sissy makes the audience earn a look inside of her,” says Pearce. “When they think they’ve seen the real her, they feel privileged.”

Her real life with Jack is hidden and ordinary by Hollywood standards. Her wardrobe comes not from the expensive boutiques on Rodeo Drive but from the Gap. “If I can’t wash it,” says Sissy, “I don’t wear it.” The difference in the way Sissy grew up and the way her daughters are being reared is a matter of scale. When Sissy was a small child, she had one horse. Madison and Schuyler have a farm of horses. When Sissy was young, everyone in Quitman knew her because her father was the county agricultural agent and she was a town ham—singing solos for area Rotary Clubs and local churches and never missing a talent show. Albemarle County residents know Schuyler and Madison because their mom is a movie star who is always being stopped for autographs. Schuyler has already been in two of her mother’s movies—The Long Walk Home and Hard Promises—and in one of her father’s, Daddy’s Dyin’ . . . Who’s Got the Will? When Sissy was a kid, her clothes came from the local dry-goods store, and she saved her own money to buy her first guitar, a $14.95 special from Sears and Roebuck. Her own children long for nothing. One evening the whole family was shopping for toys. Schuyler ran to her mother. “Come over here, Mom,” she shouted, dragging Sissy down the aisles. “I found something in this store I don’t have.”

Mercy, mercy, mercy,” Sissy Spacek moans to herself. “Just wait till I get my eyebrows on. Then I’ll be gorgeous.” It is one o’clock in the morning in Lockhart, and Sissy is sitting in a small makeup trailer on the set of Hard Promises, with her legs propped up on the counter, allowing her makeup man to buff, pat, and primp her, molding her like clay.

I sit off to the side and watch Sissy Spacek, the person, become Sissy Spacek, the movie star. Movie stars live by their wits and appearance, and Sissy is no exception. Men like the way she looks because she isn’t formidable. She arouses feelings of protectiveness. Women like the way she looks because she gives the illusion of not being beautiful, which puts her within reach. Kelvin, Sissy’s makeup man, runs a pink lipstick across her lips. He applies no foundation to her skin, but pats her cheeks with rosy Clinique liquid blush and fills in the age lines around her eyes with liquid concealer. All the while Sissy laughs and talks and moves her diminutive body to the big, round music of Etta James that is playing on the boombox.

“When I was a little kid, I used to spend a lot of time thinking about what I’d wish for if a magic fairy gave me three wishes,” Sissy tells me, surveying her own famous image in the mirror. “First, I wanted to be loved. Then, I wanted to be beautiful. And, finally, I’d wish for a million more wishes.”

It’s easy to understand how someone like Sissy Spacek, growing up in Quitman, could develop a longing for fairies and wishes. In the fifties Quitman was a small world unto itself, populated by young couples home from World War II who were drawn there by oil, the good crops of sweet potatoes, and the wild, wooded distinctiveness of the place. Girls like Sissy grew up believing that they were the center of the town and that the world was out there somewhere, theirs for the asking. “Mama told me the world was my oyster,” Sissy says, “and I believed her.”

She was born on Christmas Day, 1949, in a hospital in nearby Tyler. Virginia Spacek had put her two boys, Ed Junior, who was five, and Robbie, only a toddler of seventeen months, to bed on Christmas Eve and was adjusting the decorations on the Christmas tree when she felt the first labor pain. “Let’s go,” Virginia told her husband. “It’s time.”

From her mother Sissy learned how to tap dance to “Charlie, My Boy,” how to do the Charleston, how to spray-paint plastic ferns to make them look like feathers, how to make a game out of life. From her father Sissy learned pragmatic skills—how to keep a bank account, how to organize her time, how to make a plan and stick with it.

Sissy’s mother died in 1981 of cancer. Her father, Ed Spacek, who is eighty, still lives in Quitman in the modest green-frame and beige-brick house where Sissy grew up and returns to visit regularly. Ed is a small, trim man with eyes like fireflies, who, when I met him, was poring over the Wall Street Journal in his book-lined living room. “I don’t think any of us in the family ever called her by her real name—Mary Elizabeth,” says Ed. “The boys called her Sissy, and it just kind of stuck.” Sissy remembers that her father had a strong will. Even today, Sissy says the greatest accomplishment of her life was persuading her father to give her a horse once he had decided against it. “I bugged him for months,” she recalls proudly. “Eventually he gave in.”

When she was six years old, she and her family went to a one-room schoolhouse in nearby Coke (population: 25) and watched the Cokettes march across the stage and twirl their batons. The Cokettes wore silver cowgirl outfits and white boots. It was the first time in Sissy’s life that she felt the urge to perform. There was something magical happening on that stage, and she wanted to be part of it. “I remember sitting there in the audience, wanting more than anything in the world to be a Cokette,” says Sissy. Not a movie star, but a Cokette: She never remembers wanting to be an actress. Her favorite movies at the Gem Theater in Quitman were monster movies, but often she didn’t see the end of them. At the scary parts, “I’d always sneak off to the lobby and buy a big pickle for a nickel,” she recalls.

Sissy became the child star of the Quitman stage. She and Robbie used to sing duets—she sang alto and he baritone—and she often danced for Rotary Club meetings and school functions. She took guitar lessons from the local Church of Christ preacher. Mrs. Mary Margaret Pepper, her public school music teacher, remembers the night Sissy, still in elementary school, performed the Charleston at a PTA meeting: “She brought the house down.”

As a child, Sissy thought in two dimensions. She had an outer self—noisy and extroverted—who was a doer, and in inner self, who was a watcher, always making internal notes and keeping secrets. To this day there is a fishing box under the bed in her room in Quitman where Sissy used to store her secret papers—songs she had written, letters from friends, private notes to herself. These two sides of herself are still present. She keeps a notebook about all of her characters, writing down details she supplies about their fictitious lives—physical mannerisms, rituals, daily routines. “In every movie there’s always some physical thing that triggers the character for me,” says Sissy. “In The Long Walk Home, it was the girdle. Every time I’d put that girdle on, I’d feel my character wiggle to life.”

Small-town life was something Virginia and Ed Spacek believed in. They worked hard at giving their children a strong sense of place. Both taught Sunday school at the local Methodist church, and Virginia was active in the PTA and various women’s clubs.

Quitman is the county seat of Wood County, and the blocky brick courthouse was a second playground for Sissy and her two brothers. Their father worked downstairs as the county agricultural agent, and Virginia worked part-time on the second floor as a typist in the abstract office, earning 20 cents for every page she typed. Ed Junior, Sissy, and Robbie would ride their bicycles to the courthouse, walk upstairs, and watch their mother’s fingers fly across the typewriter.

Ed had several chances to leave Quitman for better jobs—once the king of Saudi Arabia wanted him to become his agricultural agent—but, he told me, “I had a little family. We were all real happy in Quitman, and I just didn’t dare tear up our roots.”

The Spaceks lived a solid middle-class life, but they had their own special flair. They were the second family in Quitman to buy a television (the owner of the appliance store had the first). Often Ed and Virginia invited friends over for TV viewing—sometimes just to watch the test-pattern Indian on the brown-and-white Admiral. When Sissy was about eight, her father bought a boat, and every weekend he hitched it up and drove the family fifty miles to the Lake O’ The Pines to go skiing.

Occasionally the Spaceks would be visited by a famous relative, actor Rip Torn, the son of Ed Spacek’s eldest sister. Rip grew up in Taylor, a small town 35 miles from Austin, and was already an actor by the time Sissy was in junior high school. He would show up wearing blue jeans and a white T-shirt, ready to take his cousins fishing, and, says Sissy, “All my friends thought he was the coolest thing in the world.” Having a relative in the movies made it psychologically possible for Sissy to imagine show business as a career—although as a singer rather than an actress.

In high school Sissy was a majorette, a 4-H’er, a cub reporter for her high school newspaper, the Paw Print, and eventually the homecoming queen. In her last year she tried out for the senior play but didn’t get a part. She wasn’t voted the most beautiful girl in school, but she was the cutest and the first to try new fads. For a while she wore two pairs of fake eyelashes, and people in Quitman still talk about the day Sissy cut her long hair mop-style after the Beatles made their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Small children from the elementary school stood with their noses pressed against the window of the high school, straining for a peek at Sissy’s weird hairdo. “I had to wear a hooded jacket for six weeks until my hair grew out,” she remembers, “but I learned an important lesson—never cut my hair.”

Her brother Robbie was the town track star. As a sophomore, he was the fifth-place winner of the state class 1A low hurdles. Funny and handsome, with olive skin, dark hair, and a spectacular smile, he was just enough older than Sissy—seventeen months—to have mastered the skills she lacked. He got his driver’s license before she did. They cruised to the Dairy Queen, with him at the wheel. They rode horses together. His was named Gunsmoke; hers was Buck.

It was during track season of his junior year—his best season ever—that Robbie came home one day and told his parents he felt tired. Virginia ordered him to bed. But the weak feeling hung on, and she and Ed grew worried. They took him to a specialist in Tyler and soon got the terrible news. Robbie had leukemia.

Robbie’s illness changed everything. Suddenly the close-knit family seemed to be going separate ways. Sissy’s eldest brother, Ed, was away at college at the University of Texas at Austin. Her parents began spending most of their time with Robbie at M. D. Anderson Hospital in Houston. They took turns sleeping in the chair in his room. “Ol’ Robbie was such a good boy,” says his father. “As parents we tried to protect our children from harm, but we learned there were things we couldn’t control.” Sissy stayed with friends in Quitman and shuttled back and forth to Houston to visit Robbie.

“It was a real horrible time,” says Sissy. “I’m only now beginning to understand how difficult it was for my parents. All of a sudden the world was upside down, and there was nothing I could do about it.” All she could think of was escape. The summer after her junior year, when she was seventeen, her parents agreed to let her go to New York to live with Rip Torn and his wife, Geraldine Page. Sissy insisted she wanted to pursue a career as a folk singer, and her parents decided to indulge her.

She spent the summer going to the theater on Broadway every night with Geraldine Page, watching her put on her makeup, and then finding a place backstage to see the performance. Rip and Geraldine’s world seemed new and large, and Sissy longed to be part of it. “I remember going to dinner with them and listening to them talk to famous writers, directors, and actors,” says Sissy. “I’d just sit there amazed, longing to one day be able to simply contribute to the conversation.”

As Sissy’s senior year began, her parents were living full-time in Houston. They made plans for Sissy to enroll in a private school in Houston to finish out the year. But on September 19, Robbie died. In Quitman the high school principal announced his death over the loudspeaker, and a cold silence fell over the school.

Sissy returned to Quitman to finish high school but longed to escape again and immediately began pressuring her parents to let her return to New York after graduation. At first they said no. “We’d just lost Robbie and didn’t want to lose her,” Ed Spacek says. Sissy had already been accepted at UT-Austin, and the family had put down a deposit on her dormitory. But Sissy had a strong, stubborn streak, and she would not relent. “We decided,” says Ed, “that if we didn’t let her go, she’d go anyway.”

As was his custom, Ed Spacek decided he and his daughter needed a plan. He sat down with Sissy at the round kitchen table and made a deal: He would support her—both morally and financially—for four years, but if she hadn’t made it as a singer by then, she would have to come home and go to college. Virginia handled it her own way. Once she decided to let her daughter go, she never doubted that Sissy would be a star. “Don’t worry, Sissy,” Virginia would tell her daughter whenever she called from New York, discouraged. “Once those people up there find out how talented you are, you won’t be able to fight them off with a stick.”

Robbie’s death gave Sissy’s life a sense of purpose, even urgency. At eighteen, she took on the hopes of her family. “I didn’t understand anything,” she says, waiting to be called to the set for Hard Promises. “All I knew was that I was alive and Robbie wasn’t, and I owed it to everyone—my folks, Robbie, myself—to go for it.” Her eldest brother, Ed Junior, followed her into the movie business. He recently established his own production company in Dallas.

Her makeup applied, Sissy departs to inspect the set in downtown Lockhart. Then she returns to her trailer for a steaming cup of cappuccino. I ask her how she dealt with knowing that she had gone on to fulfill her family’s destiny for achievement. She flinches and physically gathers herself up, folding her arms in front of her chest. “I never felt guilty,” she says. “What I felt was a tremendous responsibility to live all of life that I could. The bad. The good. All of it.”

Sissy and William L. Petersen, her costar in Hard Promises, are standing by the canteen trailer, eating burritos and taking bets on when they’ll finish the night’s work. “I say four in the morning, if we’re lucky,” says Petersen. Sissy hisses out of the darkness. “Count on it. We won’t be lucky. Not on this set.”

Hard Promises has been in trouble since the filming first began at the end of September. Sissy wanted to do the movie only to work with director Lee Grant, another Academy Award–winning actress. The executive producers back in Hollywood saw Hard Promises—the tale of a schoolteacher who divorces her wayward husband to marry a steady appliance-store owner—as another Philadelphia Story, but when they saw the early rushes, they panicked. The rushes weren’t funny. One of the producers began publicly undermining Grant on the set. “Oh, no,” screeched the producer repeatedly, “she’s making Ibsen again.” Five weeks after shooting began, Grant was fired.

Throughout this subdrama, there was one person who simply removed herself: the star. As the atmosphere grew more tense, Sissy focused in on her character. Some days she was so preoccupied that she looked right through members of the cast and crew. “All I could do was concentrate on making each moment in each scene work,” Sissy told me. “It’s been like the Twilight Zone on the movie. Very bizarre.”

In times of trouble, Sissy turns to her work for solace. From the beginning of her career, she has sensed that her success is tied not to some external force such as luck or who she knows but to her own will to survive. On-screen she comes across as needy, but in real life she is self-reliant and astonishingly strong.

One night, when Sissy was eighteen and new in New York City, she was working late, singing background vocals for commercials. Sissy was the last one to leave. She picked up her twelve-string guitar, hurried through an exit door, and heard the door lock shut behind her. She found herself standing on a tiny balcony, high above the street. There she was, a skinny kid from a small town, marooned on a balcony in a New York skyscraper. The next morning a security guard found her huddled on the balcony, wide awake and frightened.

That experience would have been enough to send most eighteen-year-olds running for the next airplane home, but Sissy kept going. She sang for free in coffeehouses in Greenwich Village, occasionally working for a group called Moose and the Pelicans. Once she worked as an extra in Andy Warhol’s movie Trash and even managed to cut a record under the name “Rainbo.” Within six months of arriving in New York, she was paying some of her own bills, but her goal of becoming a big-name singer still seemed out of reach.

In 1970 a young agent-manager named Bill Treusch persuaded her to try her hand at acting. She attended some acting classes and soon found herself learning sense memory and other abstract techniques. “I discovered that I could make acting work if I could tie an event in my character’s life to an event in my own life,” says Sissy. Her strength as an actress was obvious from the beginning: She had access to her emotions and understood her motives.

It was Treusch who talked her into auditioning for her first film, Prime Cut, a sordid clunker about white slavery that is dominated by two dumb, brawny men played by Lee Martin and Gene Hackman. Sissy plays the role of Poppy, an orphan sold into prostitution. Her father remembers the day she called to tell her mother she had the part. “Mama,” Sissy asked, “what if they find out I’m not really an actress?”

The first glimpse we see of Sissy on-screen is as Poppy lying naked in a pile of hay in a cow pen. The movie is a classic example of how young actresses are debased. Even Sissy’s own father says the movie is terrible—but Prime Cut got Sissy noticed. She made Poppy seem like a helpless girl from East Texas who deserved to be rescued.

It was Terrence Malick, the Austin director who made Badlands, who rescued Sissy by giving her the chance to play a female lead. Badlands is loosely based on the story of Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate, who aimlessly wandered around the Midwest in the fifties on a killing binge. Badlands was Sissy’s big break. Professionally it established her niche as a tomboy leading lady, and personally it settled what had up to then been a nagging, unresolved question: whether to change her name. “I had always intended to change my name,” says Sissy. “I just never seemed to get around to it.” She had considered changing it to Elizabeth Holiday when she first went to New York. But she found Sissy a difficult persona to drop. The role of everyone’s favorite kid sister had served her well in Quitman, and she sensed that her success was intimately tied to those roots. “It was Terry Malick who finally convinced me to keep my name,” says Sissy. “He liked the way it looked on the credits.”

It was Carrie, however, that made her famous. When she first read the script about a high school outcast who possesses psychokinetic powers, she couldn’t wait to mail it to her parents back home in Quitman. “Read this, fast,” she told her mother, “and tell me what you think.” Virginia read it, raced to the telephone, and told her daughter not to do the movie. She and Ed found it distasteful. “If you do this movie,” Ed advised, “it will be the end of your career.”

She didn’t listen. There are different kinds of intelligence, and Sissy has the kind that runs on pure instinct. She has what one director calls a “wonderful dumbness,” a child’s sixth sense that she follows no matter what anyone else says. She was drawn to Carrie because there was a poor girl in her high school in Quitman who lived in a shack and was ostracized by the popular kids. Sissy felt she understood the role. “What I liked about the screenplay was that Carrie has a moment of hope,” says Sissy. “She gets to go to her prom with a popular guy, and for a moment she knows what it feels like to be normal.”

Brian De Palma, the director, had another actress in mind for the role of Carrie. Sissy telephoned him and told him that she was scheduled to do a commercial for Vanquish, the toilet-bowl cleaner, on the same day as the auditions for Carrie. “Which should I do, the commercial or the screen test?” she asked him. “Do the commercial,” De Palma advised.

That did it. Sissy worked for days getting ready for the audition. She arrived wearing a blue sailor dress that she wore in the seventh grade, her long hair matted with Vaseline. All the other actresses were flawlessly dressed in ritzy Hollywood gear. She didn’t even speak to anyone. “I just went inside myself, focused on the character, saving my energy for the audition,” recalls Sissy. When De Palma saw her test, he instantly changed his mind. Sissy had the part.

In a critical scene in the film, Sissy used an event in her husband’s life to bring the character alive. It happened during the shooting of a nude scene when Carrie is taking a shower in the gymnasium and unexpectedly starts her first menstrual period. Sissy was worried about the scene—after all, she has to stand naked in a shower and realize that she’s covered in blood—but De Palma told her to play the scene as though she was being run over by a Mack truck. Jack was the art director for the movie—it was his job to hand her the tube of blood—and he told her that when he was a teenager, he had been run over by a car on a winter night. The two of them stood in the shower and Jack described seeing the lights of the car, hearing it approach, realizing he was going to be hit, and feeling the pain of impact. “The emotion you see on Carrie’s face is Jack’s emotion,” says Sissy.

Although she didn’t have to fight to play Loretta Lynn in Coal Miner’s Daughter—Lynn wanted her for the part—she did have to fight to sing. The director thought that Loretta Lynn’s voice should be dubbed onto Sissy’s lip synchs. Sissy was horrified and took her case directly to Lynn, who supported her. Both women believed it would be more authentic if Sissy could learn to sing like Lynn. Lynn agreed to coach her, and the two women holed up in a hotel room in Nashville, pinned sheet music all over the room, and jumped around the room, singing with their guitars. “By the time Loretta was finished with me,” says Sissy, “I was doing a pretty good imitation.”

Sissy’s mother lived to see her win an Academy Award for Coal Miner’s Daughter, but in 1981, after a long battle with cancer, Virginia Spacek died in Quitman. Sissy was with her, holding onto her hand. The day before her mother died, Sissy found out she was pregnant with her daughter Schuyler. She decided not to tell her mother because she thought it would make it harder for her to go. “I felt like I was running a relay race,” she says. “My mother was dying, my child was coming to life. I felt like someone was handing me a baton and saying, ‘Here, you’re the grown-up now.’ ”

After Robbie died, Sissy had tried to make sense of his life by becoming a success on her own. But after her mother died, the only sense she could find was in changing the direction of her work. She didn’t want to play teenagers anymore; she needed to tell stories about the lives of women. In 1984, when Schuyler was two, Sissy made Marie, a story about a crusading single mother. During the film, she was exhausted and in a funk. Schuyler walked over to her on the set, threw a Bible at her, and squealed, “Here, read this. It’ll make you feel better.” Sissy jumped up and stared at her daughter. It was exactly like something her mother would have done. “Mother,” she called, her eyes boring into Schuyler’s, “Are you in there?”

In 1986 Sissy wanted a role that would challenge her as an actress, and she settled on ’night, Mother, the story of a young woman who tells her mother one evening that she intends to commit suicide and then goes about doing it. There is nothing glamorous about Sissy’s character: She’s frumpy and dressed in gray, and she walks around three or four rooms for the ninety minutes it takes for her to carry out her plan.

During the filming, Sissy became so depressed that she would often telephone Jack at home and beg him to remind her of the details of their life together. “By the time that my character killed herself at the end of the movie,” Sissy recalls, “I couldn’t wait for the gun to go off.”

Of all the characters Sissy has played, the one she says is the most like her real self is Babe Magrath in Crimes of the Heart, for which she was nominated for an Academy Award in 1986. Babe is one of four sisters who grew up in a small town in Mississippi. She is sunny and predisposed to make the best of every situation. She winds up shooting her husband, Zackery Boutrelle, because he’s so boring that she just gets tired of looking at him. “If I ever went to jail, I’d learn to play the saxophone just like she did.”

When she talks about Babe, she instantly slips into Babe’s southern voice, slightly different from her own East Texas accent. Her chin automatically lifts, her blue eyes widen, and her face contorts. Within seconds, she has transformed herself into Babe. This, I realize, is the big payoff that acting offers Sissy. She gets to live many lives and wear many faces without having to reveal her own in public.

It is three in the morning on the set, the muggy night is unseasonably warm, and Sissy is standing behind the Lockhart Dairy Queen, waiting for her cue. “Quiet, please—rolling,” barks a grim-faced assistant producer. “Action!”

Sissy and Billy Petersen emerge from behind the Dairy Queen into the romantically lit parking lot—pink fluorescent lights here, yellow ones over there—and spot a pair of young lovers kissing in a 1948 Ford. Billy stops, points to the young couple, and asks, “Remember when we used to do that in my old Chevrolet?” Sissy smiles up at him and replies, “You mean before we used to do that in your old Buick.”

Everyone on the set is punchy with exhaustion. They do the same scene eight or nine times, until it is not romantic at all. After a few hours the large lights and boxy cameras don’t seem out of place. The set feels like a factory, and Sissy and Billy are like blue-collar workers instead of stars. I sit on the sidelines and try to imagine the scene as it will appear in the movie. It is exactly the kind of scene that has made Sissy famous. The Dairy Queen will evoke feelings of nostalgia, and the ordinary give-and-take between her and Billy will seem charming and meaningful. Its very ordinariness will work for her. She has made a career of elevating the common to the magical, the personal to the universal.

Between takes Kelvin, Sissy’s makeup man, who is following her around brushing her bangs from her eyes, whispers to her that there is a young girl who has been waiting on the street corner in Lockhart for Sissy Spacek’s autograph.

“You’re her idol,” coaxes Kelvin, grabbing Sissy by the arm and dragging her over to a dark-haired teenage girl who is standing with pen and paper in hand. Sissy says a warm hello and reaches for the paper.

“Did you get to see Loretta Lynn up close when you made Coal Miner’s Daughter?” asks the fan. “I sure did,” replies Sissy. “Ooooohhhhh!” squeals the fan. “Loretta Lynn is my absolute idol.” Sissy writes her name neatly, smiles once more for the fan, and then walks back into the pink and yellow lights of the Dairy Queen.

“I thought I was her idol,” she says, throwing her chin up to strike a movie star’s vain pose, then collapsing into laughter. “Oh, well, that’s the glitter of Hollywood for you.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Longreads