It was a shiny, blue-sky kind of spring day, and I’d decided to go for a jog. My mood was like the weather, buoyant and breezy. But as I trotted down Beverly Drive in Highland Park, my thoughts suddenly turned dark. It was Friday, and that meant my neighborhood was a war zone.

The roar of lawn mowers and leaf blowers rattled my tympanic membranes. A toxic mix of carbon monoxide, grass clippings, and dust stung my eyes and clogged my lungs. Choking, I dashed to the other side of the street, only to be ambushed by more yard-work shrapnel. After a few detours, I finally found shelter on a bench in a nearby park, where I reflected on the fact that no matter how many times I did battle with my neighborhood’s yard crews, it never got any easier. Even a 1999 resolution endorsed by the Highland Park Town Council, which calls for gas-powered blowers to run at “half throttle,” doesn’t seem to have made a difference. Either my foes are not observing honorable rules of engagement or half-throttle leaf blowing falls into the same category as half-pregnant.

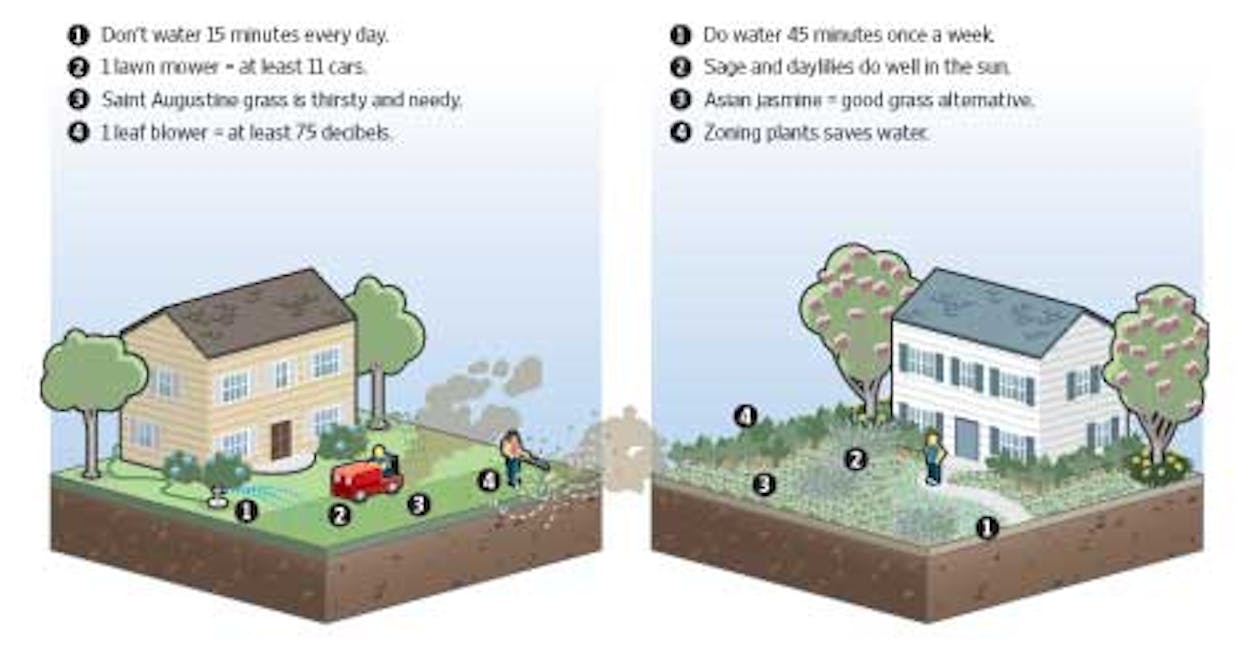

Maybe you don’t mind leaf blowers as much as I do. But I’d submit that they’re the single most potent symbol of the inconvenient truth that, regardless of how green we profess to be, we still treat our environment with insouciance and hubris. It’s a matter of vanity, really—what validates one’s social status better than a perfectly coiffed yard? So we lavish water on our grass, shrubs, and trees until they need almost constant cutting and pruning, then set zealously upon them with gas-belching machines. And yet, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, running a gas mower for an hour causes as much pollution as eleven cars; run a leaf blower for half an hour, says a 2000 report from the California EPA Air Resources Board, and you emit as much carbon monoxide as you would driving 30 miles per hour for 440 miles. Not to mention the water waste—an average household spends more than sixty gallons daily on landscaping—and the noise pollution: A blower’s whine has been known to register at least as high as 75 decibels. Whatever happened to rakes?

I wouldn’t be wasting my breath on this rant if, four years ago, I hadn’t discovered a simpler, cheaper, and, yes, greener alternative: Xeriscaping. As basic as its name is exotic, this landscaping approach forgoes a needy lawn in favor of the heat- and drought-resistant turfs and plants indigenous to such climates as Texas’s. I first happened upon the notion due to purely selfish reasons—I didn’t have a sprinkler system, didn’t want one, and I was tired of lugging a hose around my property all summer. Applying common sense, I checked with a landscaping guy and devised a plan to install some ground cover, or blooming plants that could survive a nuclear holocaust without much watering. Not only did I save myself work, I also gave the state’s beleaguered water supply a break and my yard a more authentic Texas look. Even better, my yardman doesn’t mow anymore; he runs a trimmer every few weeks, then forgets about it.

It’s proof that going green doesn’t require a rapturous epiphany—just a bit of pragmatism. But since this year represents an intentional greening effort, I recently invited Dale Groom, a Dallas County horticulturalist who works for the Texas AgriLife Extension Service, over to my house for a follow-up and an expert assessment. “The most common mistakes homeowners make,” he pronounced while surveying my property one morning, “are not knowing what’s really in their yard, not knowing how big it will get, not knowing how much water or maintenance it will require. But all this can save you money and trouble.” I’d done a nice job, he told me, considering I didn’t know much, but I really needed some three or four inches of mulch, to better retain water. I immediately resolved to perform a greening twofer the next time my tree pruners came: When they ground the trimmed limbs, I’d pay extra and have them spread the pulp in my flower beds as mulch. (Leaves also make good mulch. Don’t blow and bag them, just rake them into your flower beds.)

As for water savings, Groom said, there was little more I could do. Still, I wanted details. What are alternatives, I asked, for those with lawns of the famously thirsty Saint Augustine? He offered several: There’s buffalo grass, a native turf that thrives in full-sun conditions and requires significantly less irrigation, or there’s ground cover such as Asian jasmine, as I’d opted for, which is virtually indestructible. You can also zone your grass and water-needy plants into one area. Finally, watering less frequently but more thoroughly (once a week for 45 minutes, say, instead of 15 minutes daily) saves time and resources with no disservice to your lawn.

Groom’s evaluation prompted me to take stock of my other landscaping changes. Over time, I’ve enlarged the flower beds around our front yard’s live oak and yaupon holly tree (a dry-weather ornamental); I’ve filled one with sturdy ferns that can handle dry shade, and along one side, I’ve planted Knock Out roses, shrubs that can withstand full-sun exposure, aridness, and freezing temperatures. Thus far, I’ve been able to keep them blooming with spot watering once a week. In the second bed, my wife and I put in red salvia, or blood sage, which is native to desert climes, and along a walkway through the ground cover, we’ve planted yellow day-lilies, which positively love the sun.

All this has cost me about $5,000, and combined with the water-wise crape myrtles we already had, both my yard and I are the better for it. I don’t think much about watering anymore—unless we hit a particularly dry spell during July or August—and doing away with gas-powered tools has reduced my carbon footprint by at least 4,153 pounds. (Lawn equipment doesn’t figure into the EPA’s calculator, so this is an estimate for a mower based on the emissions of eleven idling cars; I’ll factor this into my footprint as the year progresses. Using electric or rotary yard tools also eliminates this kind of air pollution.) It’s hard to gauge the financial effect of my irrigation, because water costs in the Dallas area have risen over the past four years. But my summer bills have stayed pretty static, so I’ve at least fought off that inflation, and I estimate that my maintenance costs are about 60 percent less than my neighbors’— directly in line with what Groom says water-wise techniques should accomplish.

Now, if you’re reading this while looking out on your verdant Saint Augustine, don’t think this means you have to settle for rocks and cacti. Groom showed me a pamphlet that features the Texas Superstars, forty-odd blooming plants that love our climate (texassuperstar.com). You’ll also find a visit to the popular Aggie Horticulture Web site worthwhile, as it explains water-wise landscaping in dizzying and exquisite detail (aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu). And once you have a notion of what you want, don’t think you have to find an expensive landscaping company. I hired my guy after an Internet search for independent contractors, handed him my game plan, then let him add and subtract.

As for leaf blowers? Though communities nationwide have banned the evil things—and the EPA has proposed pollution reduction standards for such equipment starting in 2011—no Texas city has outlawed them yet. You could blame environmentally insensitive city councils, but I’ve a better candidate: preening homeowners. We’ve yet to learn that grass isn’t always greener.

Progress Report:

This month’s effect on my carbon footprint, wallet, and happiness.