At first, Russell Bonner Bentley III wasn’t sure he would survive the winter. It was January 2015 in Donetsk, a war-torn city in eastern Ukraine, and the 54-year-old Texan was sequestered inside an abandoned three-story brick monastery, exchanging fire with Ukrainian troops. He and the dozen men fighting with him had been braving freezing temperatures for weeks. From the second floor, Bentley trained his rocket-propelled grenade launcher and his Kalashnikov rifle out of a tiny slit in the side of the building. There was no electricity or running water, and wood-fired stoves provided the only warmth. “The wind came from the south, and it would blow the smoke right back into the rooms,” he recalled.

Bentley had been husky and out of shape when he’d arrived a month earlier, but on a battlefield diet of tinned meat and buckwheat porridge, the weight was melting off. With bright white shoulder-length hair and clear green eyes, Bentley had a well-developed sense of his own myth. He had led something of a swashbuckling life; he’d been an Army engineer based in Germany, a hard-partying musician in South Padre, a marijuana legalization activist in Minnesota and Alaska, and a drug trafficker on the run from the U.S. Marshals. In the early nineties, he’d even vied for a seat in the U.S. Senate.

But nothing he’d ever done compared to this. He’d been drawn into the conflict while tapping away at his laptop in early 2014. He was living in Round Rock at the time, and though Russia’s involvement in the fight—first invading Crimea, a peninsula in the south of Ukraine, and then supporting pro-Russian separatists who led an uprising in the eastern Ukrainian region of Donbass—was denounced across the globe, Bentley immersed himself in Russian media sources that blamed the war on “U.S.-backed Nazis.” He imagined the struggle as something akin to the Spanish Civil War, which had been famously portrayed by writers such as Ernest Hemingway as a fight between democracy and fascism. He began fantasizing about banding together with like-minded freedom fighters against so-called “Ukrainian fascism,” and months later he started planning his journey to Donetsk.

He arrived in early December 2014, and after a week he found a militia group, the Vostok Battalion, that was accepting foreign fighters. It was led by Alexander Khodakovsky, a then 42-year-old who has since been sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department “for being responsible for or complicit in actions or policies that threaten the peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity of Ukraine.” After enlisting, he went through two weeks of rudimentary military training and then settled into a unit called Sut’ Vremeni, or “Essence of Time,” a Stalinist communist movement. When he was asked to select his nom de guerre, Bentley, a fourth-generation Texan, anointed himself “Texas,” pronounced in Russian like the Spanish “Tejas.”

He quickly made a name for himself in combat. “Texas showed himself to be a good, hardy fighter, and an excellent machine gunner,” a writer for Sut’ Vremeni’s newspaper once noted. In battle, Bentley often wore a straw cowboy hat that he’d adorned with a red Soviet star.

Each evening at the monastery, he entertained his bunkmates by strumming his guitar and singing in pidgin Russian. At night they were careful to walk the hallways in total darkness, lest the beam from a flashlight attract the eye of a Ukrainian sniper. Once, a mortar struck the wall directly outside the room where Bentley was sleeping, sending shrapnel into his sleeping bag. He escaped unscathed.

One drizzly day in March 2015, a news crew from Ruptly, an English-language streaming video service affiliated with the Russian news channel RT (formerly known as Russia Today), stopped by Vostok’s base to report on the war. Bentley agreed to an interview. Wearing a green coat layered over his dusty black flak jacket, he focused just above the camera as he spoke. Behind him, a red Soviet Banner of Victory hung on the wall. “I’ve seen a lot of death and destruction. And I know that every person that’s been killed, every house that’s been burned, every bullet hole in every fence, every hungry dog, all the troubles of this war are because of the decisions of the United States and the influence of the United States,” he said, expertly peddling the Kremlin’s narrative of the conflict. He rested his hands—grubby from a stretch of days without a proper shower—on his AK-74, which was balanced across his lap. “I felt a responsibility to come here and show the people of Donbass and the world that not everyone in the United States supports the fascist government of the United States that supports the Nazi government of Ukraine.”

It was his first appearance on Russian state media, but it wouldn’t be his last.

That same month, while Bentley was still hoisting a grenade launcher, Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu took the stage at a ministry awards ceremony in Moscow for war correspondents. Looking out at a crowd of reporters, propagandists, and members of the military, he described journalists as “a kind of weapon” and explained that “the day has come when we’ve all recognized that words, cameras, photographs, the internet—and information in general—have become another kind of weapon, another branch of the armed forces.”

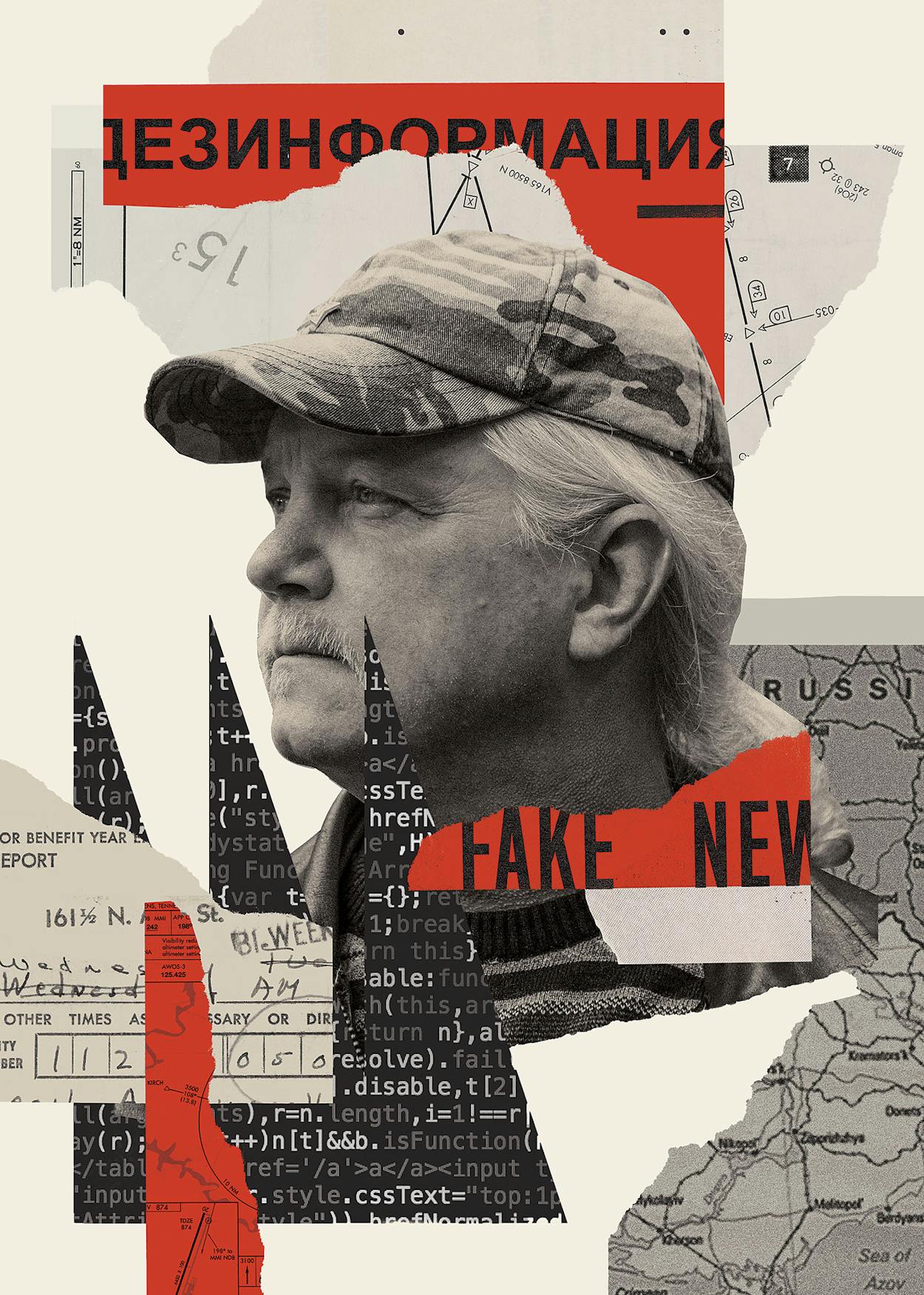

Since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the words “Russian meddling” have seemed almost permanently lodged in the tickers of cable news stations. A declassified U.S. intelligence memo released two weeks before Donald Trump’s inauguration concluded with “high confidence” that Putin himself gave an order to launch an influence campaign aimed at “undermin[ing] the US-led liberal democratic order.” From there, the revelations snowballed, eventually ensnaring a host of public officials and private entities, including Facebook, which accepted payments from Russian-backed groups that used the social media platform to target U.S. voters. This February, special counsel Robert Mueller alleged in an indictment that the Internet Research Agency, a troll farm based in a drab office building in St. Petersburg and allegedly funded by Kremlin-linked oligarch Evgeny Prigozhin, “began operations to interfere with the U.S. political system” as early as 2014.

“All the troubles of this war are because of the decisions of the United States,” Bentley said, expertly peddling the Kremlin’s narrative of the conflict.

Though Moscow has been transmitting propaganda and dezinformatsiya, or disinformation, since the Soviets came to power in 1922, the propaganda’s tenor and volume have sharpened and increased over the past decade. At a NATO summit in Wales in September 2014, U.S. general Philip Breedlove described Russia’s actions as “the most amazing information warfare blitzkrieg we have ever seen in the history of information warfare.”

The Russian propaganda campaign employs what political scientists from the nonpartisan RAND Corporation have termed the “firehose of falsehood” model: basically, an overwhelming number of half-truths and outright lies are spewed across a dizzying array of media channels. The goal is to sow confusion and exploit existing rifts inside Western democracies. And in 2008, around the time that Russia began refining this new model of disinformation warfare, there was plenty of internal unrest to exploit.

The Great Recession had given rise to political upheaval across the West. In the U.S., demonstrators protested near Wall Street when investment banks were bailed out after causing the economy to tank, and the populist anger spawned movements as varied as Occupy Wall Street and the tea party. In turn, the Russian propaganda machine exploited unsettling questions about economic inequality, globalization, and free trade. RT, the Kremlin’s biggest foreign-facing megaphone (founded in 2005 to, in Putin’s words, “try to break the Anglo-Saxon monopoly on the global information streams”), offered wall-to-wall coverage of the Occupy movement. The channel’s editor in chief, Margarita Simonyan, later characterized this coverage as “information warfare” meant to propagate discontent in the U.S.

RT and others seized on the global migrant crisis to cultivate fears about security and identity. The Internet Research Agency, for example, created a Facebook page called “The Heart of Texas” to promote Texas secession, and it accumulated more than 225,000 fans before it was shut down late last summer. In May 2016 the group organized a rally outside a Houston mosque called “Stop Islamization of Texas.” Another troll-operated Facebook page, the “United Muslims of America,” was used to organize a simultaneous counterprotest. “What neither side could have known is that Russian trolls were encouraging both sides to battle in the streets and create division between real Americans,” Senator Richard Burr said at a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing last November. Even now the American public is only beginning to grapple with the scope and effectiveness of the Russian campaign—and the extent to which people like Bentley are unwittingly drawn in.

In the waning days of 2013, Bentley couldn’t shake the feeling that his life was stalling out. Born into a wealthy family, he’d dropped out of high school and worked a factory job before joining the Army. He then bounced around odd jobs and ultimately found his calling as a marijuana activist, although trafficking the drug had eventually turned him into a fugitive. Now he was working as an arborist in Austin, renting a bedroom in a ranch-style house in Round Rock, and searching for a larger purpose. Following the Great Recession, his tree-trimming wages had dropped from $1,000 for five days of work, in 2007, to $700 for six days of work. He watched as his friends struggled as well. “People I know in Texas, Oklahoma, and Washington, they’re all working harder for less money now,” he told me.

He was fast becoming his own worst fear—a middle-aged man with a bloated waistline and no savings. “I have to find something real and meaningful in my life,” he thought, “even if it’s to be like Davy Crockett and end up at the Alamo. I have to express myself by action and not just words.”

For years his media diet had consisted of a vast constellation of Kremlin-friendly fringe websites like Veterans Today and Global Research. (He later became a fan of Southfront, which appears “to be a Russian front that deliberately obscures its origins,” a State Department official told Politico.) The perspectives that he found there, from articles lamenting the shrinking American middle class to posts about the failures of the American justice system, resonated with his own experiences.

“It was like she was looking into my soul,” Bentley said. “It was like she was asking me, ‘What are you? What are you going to do about this?’ ”

One day, alone in his bedroom and searching the internet, he stumbled across a story about the Euromaidan, a wave of public protests in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine. For three months, beginning in November 2013, demonstrators had gathered in the city center to revolt against the corruption of President Viktor Yanukovych, an ally of Russian president Vladimir Putin. In February 2014, Yanukovych fled to Russia, and less than a week later, Russian soldiers—dubbed “little green men” because they wore unmarked uniforms—popped up in Crimea. The soldiers forcefully annexed the region in March, and that spring the conflict escalated into a full-scale war when pro-Russian separatists stormed government buildings in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Donetsk and Luhansk. The Kremlin sent tanks and troops across the border to support the rebels’ fight against the Ukrainian army.

Despite nearly unanimous international condemnation of Russia’s aggression, Bentley was seduced by Putin’s view of the war. Shortly after the occupation of Crimea, Putin denounced Western leaders who’d condemned the takeover, and he claimed that “neo-Nazis, Russophobes, and anti-Semites executed the coup” to overthrow the Ukrainian government. This new regime, Putin said, was persecuting the country’s ethnic Russians, and he was stepping in to save them. Bentley, taking a cue from Russian media sources, also became convinced that the U.S. was behind it all.

Over the next few months, he joined more than a dozen Facebook groups focused on Ukraine and Russia (including one called “President Vladimir Putin Fan Club” and another titled “American Vladimir Putin Fun Club”). He connected with influential internet activists, writers for alternative websites, and talking heads on RT. And then one day in June he came across a photo of a red-haired woman who had been killed in a Ukrainian airstrike in Lugansk. Her legs had been blown off, her face bloodied. In the picture, captured just before her death, she stared directly into the camera lens. “It was like she was looking into my soul,” Bentley said. “It was like she was asking me, ‘What are you? What are you going to do about this?’ ”

He began making preparations to leave his life in the U.S. behind. He broke the news to his family, including his father, sister, and niece, at a French restaurant in Austin; uncomfortable with his politics, they didn’t press him for too many details. He sent off for a Russian tourist visa, and in the fall pared down his possessions, selling his beloved Yamaha motorcycle and gifting a pair of burgundy leather boots to his nephew. What was left fit into two large duffel bags and a camouflage German military backpack. He packed sensibly, including long underwear, Carhartt overalls, a Swiss Army knife, and a flashlight. The only sentimental tokens he allowed himself were a black-and-white passport photo of his late mother, which he tucked into his wallet, and an antique Afghan fighting knife that his globe-trotting grandfather had picked up on a trip in the thirties. He had $3,000 in cash, two thirds of which he’d collected in a GoFundMe campaign for what he billed as his “Fact Finding Mission to Donbass.”

The day before setting off, Bentley celebrated Thanksgiving with his father and younger brother at his aunt’s home in Dallas’s Preston Hollow neighborhood. That night, in Grand Prairie, he shared a bottle of whiskey with some of his oldest friends and performed a song he had written about his upcoming journey.

I’m going to Novorossiya

To be with those who believe

In dignity and honor

And know how to live free

Gonna stand beside them

Till the very end

Gonna burn my money

And make some new friends.

His father wasn’t completely at peace with his son’s decision, but the next day he drove Bentley from Dallas to Houston. Bentley boarded a plane to Frankfurt and then caught a flight to Moscow and on to Rostov-on-Don, a provincial capital on the southern Russian steppe.

Bentley took a shine to wintery Rostov. The day he arrived, he wrote on Facebook that it was like “going to the end of the Earth and back in time about 75 years, so I feel perfectly at home.” Knowing only a few words of Russian, he communicated using Google Translate. A few days later, Bentley made a two-day pilgrimage to Volgograd, a city nearly three hundred miles to the east, to see The Motherland Calls, a striking 279-foot concrete statue of a sword-wielding woman that commemorates the Battle of Stalingrad, one of the bloodiest fights in World War II. He had been yearning to visit the monument since he’d seen it in a history book as a kid in Houston, and he wept as he paid his respects to the more than 500,000 Soviet soldiers who died during the five-month battle.

A few days later, on December 7, Bentley boarded a bus to his final destination: Donetsk, the capital of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic, or DPR, a breakaway statelet that has received support and manpower from Russia since its establishment in 2014. At the checkpoint, a Russian border guard unzipped his bags and rummaged through them before asking Bentley why he was going to Donetsk. He’d anticipated this question. “To visit friends,” he said quickly, in memorized Russian. But then the guard pointed quizzically at the camouflage clothing in his luggage, and Bentley spent a few minutes fumbling through his dictionary until he sounded out “rozhdestvenskiye podarki” (“Christmas presents”). The guard gave him a knowing smile and moved along to the next person in line.

Once the bus pulled into central Donetsk, he heard the rumble of not-so-distant shelling for the first time. The front, which snakes roughly 280 miles through the DPR and the self-proclaimed Lugansk People’s Republic, to the north, was a few miles away. He checked into a small hostel called the Red Cat, where one of his contacts, a blogger named Christian Malaparte, had been living for a few months. Bentley stayed up late that first night talking with Malaparte and listening to bursts of shelling. “It is an interesting feeling to walk around a city knowing Death can fall upon you at literally any second, just by total random chance, but in truth, isn’t it really like that for all of us all the time?” he wrote on Facebook the next day.

On his fourth day in town, he was asked to report to the Ministry of State Security, where he was interrogated for six hours about whether he was an American spy. When his interrogator asked him, “What are you going to do if the army won’t take you?” he replied, “I’ll do counter-propaganda.”

He eventually spent six months on the front lines, but in June 2015 his unit was transferred to a special forces battalion. At his age, Bentley was ill-suited for this new post, and he realized he could perhaps be put to better use as an English-speaking “information warrior,” creating the kinds of media that drew him into the war to begin with. He started out by posting shaky homemade videos on his Facebook page, and soon he began appearing in videos produced by Sut’ Vremeni. In one dispatch he traveled to a civilian house that had recently been shelled and alleged that the damage was the “work of the Ukrainian Nazis that the United States and Barack Obama back, direct, pay, and arm.”

In August he debuted a twice-weekly FM radio show on Donetsk’s Radio Kometa. “This is Tejas, coming to you live on Radio Free Donbass from our secret underground bunker in Donetsk City Center,” he intoned, with an exaggerated twang. “We wanted to do information war—information defense—against the propaganda that the Western media has launched against the people of Donbass and the people that defend Donbass,” Bentley explained to his audience of local and online listeners. “We are going to bring the truth to you live from here.”

Bentley was a natural with a microphone, but he was kicked off the show a few months later, after he clashed with his boss over pay. (In a cache of leaked emails from the press office of the DPR, Bentley’s boss described him as suffering from a “drinking problem” and “medium-level” narcissism.) That December, Bentley launched a YouTube series called “Donbass With Texas.” The show, which now numbers 31 episodes, is distributed with English and Russian subtitles on Sut’ Vremeni’s various YouTube channels. In the inaugural episode, Bentley explained that he hoped to bring communism 2.0 to Donbass. But unlike the Soviet Union, he claimed, this new state would be friendly to religion. “We’ve got Lenin and we’ve got God on our side and cannot be defeated,” he said.

Bentley has a knack for dramatizing the violence. The conflict has killed more than 10,000 people, injured almost 25,000, and displaced more than 2 million. But to hear Bentley tell it, Russian soldiers weren’t involved in any of this at all. He never mentions that the DPR regularly shells civilian neighborhoods on the Ukrainian-controlled side of the front line, and he routinely promotes false stories. For instance, he once created a ten-minute video “investigation” about Malaysia Airlines flight MH17, which was shot down in July 2014 near the town of Hrabove, in separatist-controlled eastern Ukraine, killing all 298 people on board. Bentley claimed that the plane was downed by Ukrainian fighter jets “in an act of premeditated mass murder.” However, a Dutch-led joint investigation team concluded that it was shot down from a territory controlled by pro-Russian fighters by a missile launcher trucked in from Russia. Bentley’s theory is among at least eight conspiracies disseminated by pro-Russian outlets in an attempt to distract from the untidy truth.

In Donbass, Bentley quickly emerged as something of a folk hero. To date, the massive catalog of videos he has helped create or appeared in has been viewed more than four million times. In a September 2015 video, he visited a high school class in Makiivka, a city northeast of Donetsk, and a teacher introduced him to her students as “an almost legendary person in Donbass.”

Bentley now makes occasional appearances on Russian state TV, which is watched by millions. He has also become a regular guest on the streaming radio show of Jeff Rense, a Holocaust denier who hosts shows on his network for David Duke, a former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard, and Don Black, the founder of the neo-Nazi site Stormfront.

During Bentley’s first prime-time appearance on Russian television, he told a correspondent from the channel NTV that he had come to Donbass to defend the region against “American-style democracy.” He said that there were also Americans fighting with the Ukrainian army. “Most of them are scoundrels,” he said. “It will give me great pleasure to pull the trigger.”

Reaching Donetsk these days is tricky. The city is set on the banks of the Kalmius River, on a flat stretch of steppe dotted by slag heaps—little black pyramids known locally as terrikons—produced by the area’s many coal mines. Though an economically depressed city now, it was an important industrial center in Soviet times. I made my first and only other trip to the city in 2006, when I worked at the Kyiv Post. Back then the trip was simple: a short if bumpy plane ride from Kiev on an old Soviet jet. But today the Donetsk Airport is a bullet-ridden husk along the front line, and the best way to even get near the city is by train and then by car.

The highway overpasses leading into Donetsk were eerily deserted, but as we approached the city center, a veneer of normalcy emerged.

I did exactly this last spring, taking an overnight train from Kiev to Kostiantynivka, 45 miles north of Donetsk, then driving a circuitous route to avoid the heavy fighting before crossing out of Ukrainian-controlled territory.

In no-man’s-land, we passed a series of red-and-white warning signs that cautioned drivers not to stray from the pavement: “DANGER! MINES!” A farmer, disregarding the signs, tilled the land almost to the road’s edge.

The highway overpasses leading into Donetsk were eerily deserted, but as we approached the city center, a veneer of normalcy emerged. The sidewalks were clean and well-kept, parks were filled with tidy flower beds, and young mothers pushed strollers and carried bags of groceries. Still, the pockmarked buildings laid bare the fact that it was a war zone.

I’d come because I wanted to meet Bentley, so I could understand his motivations and ambitions. Did he truly believe in the message he was pushing? What was he hoping to accomplish? He’d agreed to meet, and the following morning he awaited me at the Kalininsky 4/4 memorial, an abandoned mineshaft where Nazis and their collaborators disposed of more than 75,000 bodies during their occupation of the city during World War II. When I arrived, Bentley was standing in front of the faded redbrick entrance with his Sut’ Vremeni videographer, a lanky twentysomething from Kiev. Bentley wore a leather jacket and gray camouflage pants, and he solemnly removed his baseball cap when we approached. “The Nazis brought people here every day—dead bodies, but also live people—and just threw them down this shaft,” he explained. “When you murder a whole family by throwing them down a hole, do you throw the parents or the kids in first?” He paused and then pivoted to a questionable connection. “That’s what we’re fighting here. That’s the kind of monsters we’re fighting with.” (Equating the current conflict with World War II is a common tactic employed on Russian television, but in Ukraine today there are no new mass graves and there is no genocide. Neo-Nazis do exist in Ukraine, but they’re a fringe element that does not enjoy wide popular support; the same is true in Russia.)

Bentley led me back outside to call a taxi, and as we waited, he lit a cigarette and handed me a few gifts: a can of halal horse meat, a Velcro DPR flag patch, and an issue of Sut’ Vremeni’s newspaper. “Speaking of halal,” he said, as if someone else had brought it up, “the DPR defense minister announced two days ago that they’ve documented five hundred jihadists who have come to Mariupol from Syria.” Bentley speaks in a raspy baritone, the voice of a man who has smoked for all but 13 of his 57 years, and peppers his speech with “bro” and “dude.” In many respects he can be charming, though it’s difficult to keep up with his outlandish claims. A quick bit of research revealed, for instance, that Mariupol, a Ukrainian-controlled coastal city about 65 miles south of Donetsk, is not the home of five hundred jihadists, and this false claim about ISIS fighters has been repeated in Russian media since the fall of 2015.

Bentley was eager to show me the conflict’s toll on the civilian population, so we headed to a neighborhood near the front. As we drove, we passed a Stalin-themed coffee shop that had sprung up near the bus station, beside a store selling all the trappings of statehood—red, blue, and black DPR flags, DPR coffee mugs, and framed portraits of Putin and DPR leader Aleksandr Zakharchenko. Life near the front is precarious, but around 800,000 people still live within three miles of both sides of the front line. Most of the people who can afford to flee Donetsk have already done so, and in some areas families have been living in bomb shelters since the start of the war.

We stopped at a brick home that had been shelled two weeks earlier. The house’s sole inhabitant, 75-year-old Galina Frolova, died from shrapnel wounds when an artillery shell struck her kitchen late in the evening. She was one of sixteen civilians to perish in the war in March 2017, according to United Nations estimates. Her backyard had been reduced to rubble; mismatched shoes were scattered about, and the contents of a jar of shattered tomato sauce had dried into a maroon crust near the collapsed kitchen wall. Bentley paced across the detritus-strewed backyard in his black leather boots, furiously describing what had happened. The first mortar shell, he said, had hit in front of Frolova’s gate. She had been in the kitchen on a panicked phone call with her daughter when the second shell exploded. “Two weeks ago, this was just a normal backyard, with some little old lady working in her garden,” Bentley said as he stepped over a pile of crumbled brick. “There’s no military reason for bombing this area.”

Exchanges of artillery fire occur almost nightly here, and innocent civilians on each side of the front regularly meet similar ends. Every day, monitors for the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, a Vienna-based group tasked with observing conflicts around the world, patrol the front line, and they have faulted both sides for hiding artillery in or near civilian neighborhoods. Just days before Frolova’s death, the OSCE noted that an elderly couple in a Ukrainian-controlled part of Zaitseve, northwest of Donetsk, had also died when their home was shelled. On the night Frolova’s home was hit, monitors recorded 520 explosions in and around Donetsk, but they couldn’t precisely pinpoint who launched the shells that killed her.

Bentley, however, derided the OSCE’s efforts, calling them “spies” for the Ukrainian army. Then he drew another dubious connection, this time between Frolova’s death and America. “Just like they’re doing in Syria, just like they’re doing here, just like they did in Libya, just like in Iraq, just like in Afghanistan, there’s no place the U.S. has liberated that hasn’t turned into a complete shithole,” Bentley said.

Later that night, in the center of Donetsk, we sat down for dinner at a Mexican joint called Kaktus that also serves sushi and pizza. The walls were covered with Southwestern kitsch, and Bentley settled into a chair with a cactus-heavy mural at his back. He ordered a Steak San Antonio and a bottle of vodka for the table. By dining with my accompanying photographer and me, he was disregarding the advice of his fiancée, a 37-year-old woman named Lyudmila, a coal miner’s daughter who had been his Russian tutor. “She’s like, ‘Don’t eat anything with them, they might poison you!’ ” he said. “It’s not a completely unreasonable concern.”

Between bites of an approximation of nachos—rigid chips slathered with mozzarella and tomato sauce—Bentley began to tell me his life story. Born in Austin in 1960, he spent his earliest years in affluent Highland Park, in Dallas, and his family relocated to Houston when he was eight. From birth, he was a firecracker, prompting his great-grandfather William Perry Bentley to write to a colleague when Bentley was seven months old that he “commands a lot of attention despite his age and weight.” The family was well-off thanks to William Perry, an MIT graduate who moved to Texas at the turn of the century from New England and patented a new form of asphalt. His company, Uvalde Construction, paved roads throughout the state.

If Bentley had stayed on the path set out for him, he would have enjoyed a comfortable life. But he chafed at the structure of the classroom, preferring to hole up in his bedroom with his dog-eared copy of Ernesto Che Guevara’s Bolivian Diary. “I really had no trust or respect for authority, from the president all the way down to the vice principal of my school,” he told me. He spent the summer before eighth grade hitchhiking and smoking pot, but his father, a stern disciplinarian, grew tired of his son’s insubordination. He sent thirteen-year-old Bentley to Discovery Land, a wilderness camp outside Bryan for “emotionally disturbed adolescents.” Bentley spent the next three years there.

While he was away, his family moved to Brownsville and his father opened a maquiladora across the border, in Matamoros’s industrial zone. At sixteen, Bentley attended high school in Brownsville for a semester before concluding that formal education was not for him, and then he landed a welding job at his dad’s factory. The work was demanding and paid only $98 a week, so Bentley soon moved to Austin, where he got by trimming trees and selling marijuana. His father persuaded him to join the Army when he was twenty by giving him a Rolex and promising to pay for his college and set him up with a decent job when he graduated. After basic training, Bentley spent the next three years as a combat engineer stationed in Germany and Louisiana. He didn’t see combat but judged the experience “a good adventure” nonetheless. “The Army is like socialism—everybody’s pretty much equal,” he said.

While Bentley was in the Army, his father lost most of the family’s fortune in the 1982 peso devaluation. Bentley’s parents moved to South Padre Island and opened a restaurant, the Pantry and Grill Room, and after Bentley received an honorable discharge from the Army, he waited tables there. He earned tips easily. “He could make you feel like the only person in the room,” said Teresa Harrigan, a former co-worker. “He was very suave and definitely good at making people feel important and special regardless of who they were.” When he wasn’t working, he feasted on South Padre’s charms: cocaine, spring breakers, and booze. He also played guitar in a local group called the Asbestos Band. With a baby face, slim frame, and strawberry-blond mullet, Bentley developed a reputation as a lothario.

In 1990 he followed a girlfriend up to Minneapolis and got a job cutting trees, but it occurred to him that he’d be far better off selling marijuana, which he could purchase cheaply in the Valley. He started out by riding a Greyhound to Brownsville, sending weed home via UPS, and then taking the bus back north. He soon purchased a new car with his proceeds, and the operation expanded. He and his partners stuffed bricks of marijuana into car seats, packed them into semitrucks, and even loaded them onto small planes, moving them all around the country.

At the same time, Bentley threw himself into his first love: political activism. He joined the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws and the Grassroots-Legalize Cannabis Party, founded in 1986, and he began calling himself Russell “Bongo” Bentley. He donated to the cause from his personal coffers and in 1990, at the age of thirty, ran for U.S. Senate against the Republican incumbent and a then relatively unknown political science professor named Paul Wellstone. In his candidate statement to the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Bentley promoted hemp’s potential as an alternative fuel and touted the billions of dollars taxpayers could save by legalizing marijuana. Although he lost, he received a respectable 29,820 votes in the general election.

Some questioned the wisdom of fighting for marijuana legalization while simultaneously trafficking large quantities of the drug, but this risk didn’t seem to give Bentley pause. “He was blinded by the cause he was fighting for,” said his friend and former bandmate Phil Loveland, who had moved to Minnesota from South Padre around the same time as Bentley.

Bentley’s political beliefs further crystallized during a trip to Cuba in the mid-nineties. Over dinner with a captain in the Cuban army, Bentley said that he had long considered himself a socialist.

“Well, I’m a communist,” she replied.

“What’s the difference?” he asked.

“A communist is someone who is willing to fight for socialism,” she said.

Russell thought for a moment before answering, “Then I’m a communist too. I’m willing to fight for it.”

Around this time, Bentley discovered the internet’s potential for expanding the reach of his platform. In October 1995, when fellow activist Arlin Troutt went on trial for conspiracy to distribute one hundred kilograms of marijuana, Bentley penned regular dispatches from the federal courthouse and posted them on internet message boards. After his friend’s conviction, Bentley’s online rhetoric took a more apocalyptic tone: “And as for finding a new land of the free and home of the brave, I say this—we already know this land is not free, it’s become the biggest police state that humanity has ever seen. . . . It’s up to us to set it right. It’s our country, isn’t it?”

The following February, a SWAT team burst through the door of Bentley’s Minneapolis home and arrested him. “We got Bongo,” an officer reportedly said over the police radio. A federal grand jury in Brownsville had indicted him on one count of money laundering and six counts of possession with intent to distribute marijuana. The indictment alleged he had smuggled more than 1,500 pounds in total. He pleaded guilty to one count and received a jail sentence of five years and three months.

According to Bentley, he was transferred to a halfway house in Minneapolis in 1999. He was slated for release before the end of the year, but he failed a drug test in August. He couldn’t bear returning to prison to serve out his full sentence, so that evening he used a pocketknife to shear off his ponytail. He then sliced through the window screen of his bedroom and slipped into the Minnesota night.

The next few years were peripatetic and paranoid ones for Bentley. “He was living in hell,” Loveland recalled. Bentley assumed the identities of multiple friends, carried a pistol everywhere, and obsessed over police scanner traffic. Despite his fugitive status, he moved to Alaska to work on a ballot initiative to decriminalize marijuana. On the campaign, he kept a low profile. “It makes sense now why he shied away from camera time,” said Lincoln Swan, one of his co-workers at the time.

Ultimately, after almost eight years on the lam, he was arrested in Snohomish County, Washington. According to Bentley, he’d gotten into a squabble with a roommate, and after police ran his prints he was sent to serve out his sentence at a maximum-security federal prison. A year later, in the summer of 2008, he walked out into the world with an impassioned distrust of the federal government.

On most days Bentley sticks to a few well-established routines. When he’s scheduled to film a new video, he chats with his cameraman first thing in the morning and then heads out to capture footage in whichever neighborhood has been shelled the previous night. On other days he pours himself two cups of coffee and hunkers down on the fold-out couch that doubles as a bed and an office. There he peruses his favorite websites, composes blog posts, and hatches plans for new projects (he’s got a memoir in the works).

As he showed me around Donetsk for several days, his celebrity was evident. People gave him high fives when passing on the sidewalk or excitedly yelled, “Texas!” when they spotted him from afar or stopped and asked him to take a selfie, as our cab driver did one afternoon. When we visited the city’s World War II museum, a docent jumped from his chair and yelled, “Comrade Texas has arrived!”

“Everybody knows my face,” Bentley told me.

His local fame is unsurprising, given that there are few charismatic Texans willing to forcefully articulate the Kremlin’s point of view, but his rise as a prominent voice in Donetsk also portends a nefarious development in the information war.

Before arriving in Ukraine, I was curious to learn whether Bentley was being paid by Russia for his work. He has developed ties to some of the most powerful media channels in Russia, and he is Facebook friends with several people who work for publications operated by the Internet Research Agency, the media factory named in Robert Mueller’s February indictment. Bentley has also appeared in articles and videos on at least ten websites run by the agency. Yet he denied ever receiving payment. “See the hole in my boot? You see my car? No, ’cause I don’t have one. My apartment is a hundred bucks a month,” he said. “I wish I was getting a check. I don’t get paid by anybody. The only money I get is what my friends send me here because they like me and they like my work.”

When we visited the city’s World War II museum, a docent jumped from his chair and yelled, “Comrade Texas has arrived!”

Bentley, I discovered, is a new kind of soldier in the information war, a freelancer who has garnered a loyal following precisely because he claims to be independent from state or corporate control. In truth, of course, he often echoes the talking points spun out by Russian news sources. And in that respect, he is part of an emerging crop of self-styled information warriors loyal to authoritarian regimes. “There are more of these actors cropping up in conflict zones around the world,” said Tanya Lokot, an assistant professor at Dublin City University’s School of Communications who studies how digital media has been used on both sides of the Ukrainian conflict.

These actors include the likes of Mimi al-Laham, who churns out conspiracy theories advocating for Syrian president Bashar al-Assad on Twitter; Eva Bartlett, a blogger who claims the White Helmets’ rescues of Syrian civilians are staged; and Graham Phillips, a YouTube vlogger who moved to Donetsk after a stint in Kiev. Though their reach may be limited compared with the likes of Russian state media, the conspiracy theories they promote tend to ricochet around the web, making the leap from alternative media websites to Russian television, and after gaining traction on social media, burbling up to the mainstream. As a result, parsing the truth has become more elusive than ever.

Bentley, for example, claims he’s on a mission to stop World War III, a conflict he believes will pit “one percenters” in the U.S. and European Union against Russia. He thinks the conflict in Donbass could be that war’s opening salvo. (He also argues that the election of Donald Trump has forestalled the conflict, for now.) But he concedes that stopping World War III is “rather a large task for an old poet that smokes and drinks too much, but I’ve got some good friends helping me.”

Bentley introduced me to a number of those friends, many of whom were fellow foreign fighters. There was a Serbian sniper named Dejan “Deki” Beric, a boyish 43-year-old with floppy brown hair and the unsettling habit of fingering the Velcro on the handgun holster of his cargo pants while he spoke. He joined the fight in Ukraine in revenge, he said, for NATO’s 1999 bombing campaign in Yugoslavia and claimed that “every war in the world has been started by American journalists.” There was also Alexis Castillo, a 29-year-old Colombian-born Spaniard who had been involved in anti-fascist activism in his hometown of Murcia. “I’m doing more than I could do in Spain,” he said. And there was an eccentric 30-year-old Frenchman named François Mauld d’Aymée, who had traded his life running a tutoring company in London to spend three months in 2016 fighting alongside the Kurdish Peshmerga against ISIS in Iraq. Last year he showed up in Donetsk, where he landed a job as a teacher at a local university and as an opera singer. “I feel like Donetsk is more European than Europe,” Mauld d’Aymée gushed, before railing against the “globalists” and “Islamists” he believes are taking over France. (Though Bentley has plenty of friends in Ukraine, he seems to have fallen out of contact with his family. His sister, who declined an interview request, said she no longer speaks to her brother. He’d remained close to his brother until his sudden death from heart failure, in October 2015.)

Bentley, like a growing number who harbor a skeptical view of America and the West, has found a savior of sorts in Putin. Though the global economy has partly recovered since the Great Recession, Putin has continued to appeal to globalization’s discontents on both the far right and far left in the U.S. and Europe, lending credence to the idea that politics isn’t a spectrum, it’s a circle: taken to their extremes, the left and right converge.

Bentley’s main critiques of American society, from flat wage growth to the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few, largely mirror the party line for progressive American Democrats. But he goes far beyond that. Like the Austin-based conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, Bentley believes that the world is run by a shadowy cabal of oligarchs who control everything from the Western media to the appointment of the next U.S. president.

The more time I spent with Bentley, the more I realized his worldview is rife with contradictions. He denounces America’s totalitarian impulses but waxes poetic about foreign strongmen past and present, including Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad.

He criticizes most Americans for being checked out. “One of these days, the swords will come out. And on that day, all the people in the United States who were willing to let their government commit war crimes all around the world as long as they can still buy a six-pack and watch the Super Bowl, they’re going to get what they deserve,” he said.

In August 2016 Bentley told a writer from the Russian website RIA FAN that he would never again visit his homeland. “If I go back to the United States, I’ll be driving a T-72 tank, and I will go there to make a revolution,” he said.

But considering his emerging role in the war, climbing into a tank is no longer necessary. As he said in a YouTube video in early 2017, “My words are my bullets now, and they have a range that goes all the way around the world.”

One morning in Donetsk, Bentley and I hailed a taxi to a satellite office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, a three-story building with a tan tile exterior where Bentley was headed to pick up his new passport. He wore burgundy cowboy boots and had pinned a red star to his khaki jacket with the words “Defender of Donbass” written in Russian.

Ever since his Russian tourist visa had expired, in December 2014, Bentley had been stuck in the DPR. There is no Russian consulate in Donetsk, so he couldn’t apply for a new visa, and he was a wanted man in the rest of Ukraine. Thus, a DPR passport, which would allow him to travel to Russia, was his only way out of eastern Ukraine. (Though Russia doesn’t officially recognize the DPR as an independent state, it does allow holders of its passport to enter its territory without a visa.)

Trailed by his cameraman, Bentley strode into the office of Natalya Gaivoronskaya, the district’s chief migration officer, who was standing behind her desk in a pressed blue uniform. Knowing she would be on-camera, she had made a special trip to the hair salon. “Russell Bentley, here for my passport of Donetsk People’s Republic,” he announced in Russian.

Gaivoronskaya pushed a piece of paper across her desk for Bentley to sign. “That’s it. Congratulations,” she said, and handed him the slim booklet. “Thank you very much,” he said. He gazed at the maroon cover and gold embossing. “I’m very proud. I’m very, very happy.” He shook the migration officer’s outstretched hand. “My new country.”

Gaivoronskaya’s six-year-old son, wearing green camouflage fatigues adorned with Russian and DPR flags, had been patiently waiting to get a photograph with Bentley. The boy hopped up from his chair, and Bentley grinned as he shook his hand.

Afterward he went outside to make a statement on-camera. His fiancée, Lyudmila, tucked a stray strand of hair behind his ear, and Gaivoronskaya stepped outside and looked on as the cameraman offered suggestions about what to say. “You can say this passport is like a symbol of freedom,” he said, gunshots cracking in the distance. “You can also say this is like an island of freedom. People from different countries can come here and join us.”

“I want to thank the kind, good people of the Donetsk People’s Republic for giving me their friendship, their brotherhood, letting me be part of the big family that our republic is,” Bentley said. “It is my new motherland. I will defend it, I will protect it, and I will help this republic to make a better world. This passport is a symbol of the struggle against fascism around the world.”

In September Bentley and Lyudmila were married in an Orthodox church in Donetsk. Footage from their wedding ceremony and festivities aired on Sunday night prime-time TV throughout Russia. Russell wore a white dress shirt with a black leather vest and a red bandanna fashioned as a cravat; outside the church, he donned a black suede cowboy hat. “The cowboys and the Cossacks are now together, and together we will make a better world for everybody,” he said after the ceremony. At the reception, they served barbecue, vodka, and pink wedding cake. In the pages of the Donetsk edition of the popular Russian tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda, a journalist wrote, “Another foreign citizen could not resist the charms of a Donetsk beauty.”

The next month, Bentley made his first trip to Moscow to “meet some bigwigs,” he wrote me, though he was uncharacteristically coy about what he did in the Russian capital. And in November he went on a two-week road trip around the Crimean peninsula, meeting members of the local militia and visiting churches and historic sites along the way. In Sevastopol he spent time with several Night Wolves, a Russian nationalist biker gang led by Alexander Zaldostanov, a personal friend of Putin’s who boasted to Vice News in 2015 that he had long encouraged the Russian president to take over Crimea. Bentley presented Zaldostanov with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s he’d stashed in his coat pocket. “I’ve known a fair number of [Bandidos and Hells Angels] in my time, but [Night Wolves] are different,” he wrote me that evening. “They’re REAL tough guys, as you might expect from Russian bikers, but they are the Good guys too. Otherwise Vladimir Putin wouldn’t ride with them.” A few days later, Zaldostanov invited him back to film a cameo in his movie, Russian Reactor, which Bentley described as “a patriotic vision of the last 100 years of Russian history.”

When I was still in Donetsk with Bentley, I tagged along as he and a few friends gathered at an underground bar to celebrate his new citizenship. Late into the evening, his jubilation had not faded. In our time together, he often mused about how much he loved his new life. “This is the best and happiest time in my life,” he told me. “Not a lot of guys can say that at my age.”

At one point that night he proposed a toast. “As of today, I have a new country,” he proclaimed. “If the U.S. starts World War III, I’ll fight on this side, and I’m happy to see the U.S. destroyed just like Germany was!”

His friends all raised their glasses and cheered.