Twenty years ago music came out of a big brown box called a hi-fi console. You could stick it in a corner, shut your eyes, and pretend you were sitting in a concert hall.

You were only fooling yourself.

Instead of a big brown box you now can buy the kind of equipment audio engineers didn’t even dream of in the 1950s—tuners that bring in stereo radio broadcasts, speakers that catch almost every nuance of the actual performance, and amplifiers that bring a 100-piece orchestra or a ten-piece rock group into your lap. There are still brown boxes around, infinitely better than their ancestors; and there are “compact hi-fi systems” and “portable phonographs.” But the best way to get concert-hall quality high fidelity is to assemble a series of components. The components include loudspeakers (two for stereo, four for quadraphonic sound), an amplifier with or without a built-in AM-FM tuner, a record player, and perhaps a tape player.

The myriad technical specifications associated with a true high-fidelity system are directed toward a few simple goals. First and foremost, a good sound system must be capable of reproducing all the tones or frequencies contained in the original program source at their correct relative intensities—what the audio world calls “flat frequency response.” Since the limits of human hearing are generally considered to extend from twenty vibrations per second to about 20,000 vibrations per second, ideally all the components of a high- fidelity system should be responsive to that range of frequencies. All-in-one console units must generally restrict frequency response, particularly at the low bass extremes, since the vibration from their built-in loudspeakers would otherwise induce vibration into the phono pick-up system and could cause a loud, howling “feedback” sound. So, the first requirement in a good sound system is that the loudspeakers be physically separated from the other components. This requirement is also necessary for proper stereophonic dimensional effect.

In addition to reproducing all musical frequencies at the proper loudness, the components should not introduce unwanted electronic tones or noise not present in the original program. Noise, whether it be in the form of a steady hum (usually generated from sources related to your home power line) or as a random “hiss” (often associated with weak radio signals, poor-quality tape recordings, or discs containing a high level of surface noise), detracts from musical enjoyment.

The system, finally, must have dynamic range—the ability to reproduce faithfully the very loudest as well as the very softest passages of a musical program. A loudspeaker which cannot accept powerful electrical signals fed to it without introducing distortion is as undesirable as an amplifier or receiver that introduces high orders of distortion to the electrical signals before they ever reach the speakers. In short, each component of the system must be compatible with each other component, and each should be of a high enough quality within the owner’s budget so as not to denigrate the performance of the others.

The two most popular music sources are records and FM radio. Unlike AM radio, which is generally limited in the range of sound it can transmit and is plagued with static and other interference problems, FM radio can be received with noise-free quality and is transmitted with fidelity extending almost to the limits of human hearing. In addition, more than half of all U.S. FM stations transmit all or part of their programming in stereo, with left and right channel signals transmitted over a single station but separable into two signals by home stereo tuners or receivers. The unit of a hi-fi system which picks up and amplifies these signals is called an FM stereo tuner and may be a separate component or part of a single component known as a receiver.

A receiver consists of three elements which can be combined or acquired separately. The tuner picks up the high-frequency radio signals and converts them to much lower frequency audio signals; the pre-amplifier amplifies program signals and allows their signal and tone to be stepped up; the power amplifier further steps up the signals and converts them to the energy necessary to activate loudspeakers so the signals can be heard.

A record player consists of three elements: the turntable, the tone-arm which contains the pickup or cartridge with its stylus (“needle” was the name used in pre-hi-fi days). The turntable rotates at a constant speed with as little induced vibration as possible. These seemingly simple requirements, if not met, can lead to distortion. The tone arm should move freely and position the cartridge so that the stylus can trace the complex undulations inscribed in a record groove with a minimum of downward force (tracking force). The cartridge should respond uniformly to all audio frequencies and translate physical motions generated by the record grooves into accurate electrical signals. The better cartridges employ magnetic or electro-magnetic principles instead of the ceramic or crystal elements in lower quality cartridges. Diamond styli are almost invariably used these days since they retain their precision-ground shape up to 1000 hours of record play and are less apt to damage the grooves of records. The quality of a cartridge, which is often purchased as a separate item, is, in part, governed by the quality of the turntable system chosen. Inexpensive record changers may not be able to accommodate high-quality pick-ups, while top-grade turntables should not be fitted with mediocre cartridges.

In this country, the “automatic” turntable or record changer is still favored over the “manual” machine, though that trend seems to be in reversal as more high-quality manual machines are imported. The convenience of stacking several records is the obvious advantage of the automatic record player, while the more rugged, less complex single-play turntable/tonearm combination is cited as a plus for that device. While a variety of motor types and drive systems are used to power turntables, the important thing to remember is that the goal of each system is to provide constant rotation, with as little distortion as possible. Other features, such as number of speeds, cueing levers, tracking force adjustment capability, and anti-skating adjustment, are all provided on the better manual and automatic machines.

Whether you purchase a single-piece receiver, or a separate tuner and amplifier, the question of how much audio power you will need is probably the first you will confront when you start shopping for a component hi-fi system. With power available from as little as ten watts per channel to hundreds of watts per channel, it’s not surprising that the layman doesn’t know where to begin. One thing is sure—the more power your amplifier or receiver can deliver, the more expensive it will be.

But price isn’t the only facet you should consider. The choice of amplifier power capability depends largely upon the type of speaker you select, the size of your listening room, and your preferred listening levels. A ten-watt amplifier feeding a very efficient speaker system may be more than enough to give you all the sound you want. Or a 100- watt amplifier driving a very low-efficiency speaker system may not produce enough sound.

Ideally, the speakers you like should be connected to several amplifiers or receivers within your proposed price range and listened to at the loudest sound level you think you will want in your home before you decide on this important “match” for a system.

A point to consider: sound (or human hearing) is not linear: doubling the average power fed to a loudspeaker does not result in an audible doubling of sound level. For a sound to appear to be “twice as loud” as some other sound requires an increase in power of ten to one. Then, too, modern recordings often have a considerable dynamic range, so that, while the average musical content may demand an average power level of just a watt or two, sudden peaks in the recorded music may require many times that amount of power for a short time. An amplifier incapable of delivering that required power then distorts or “clips” the musical waveforms.

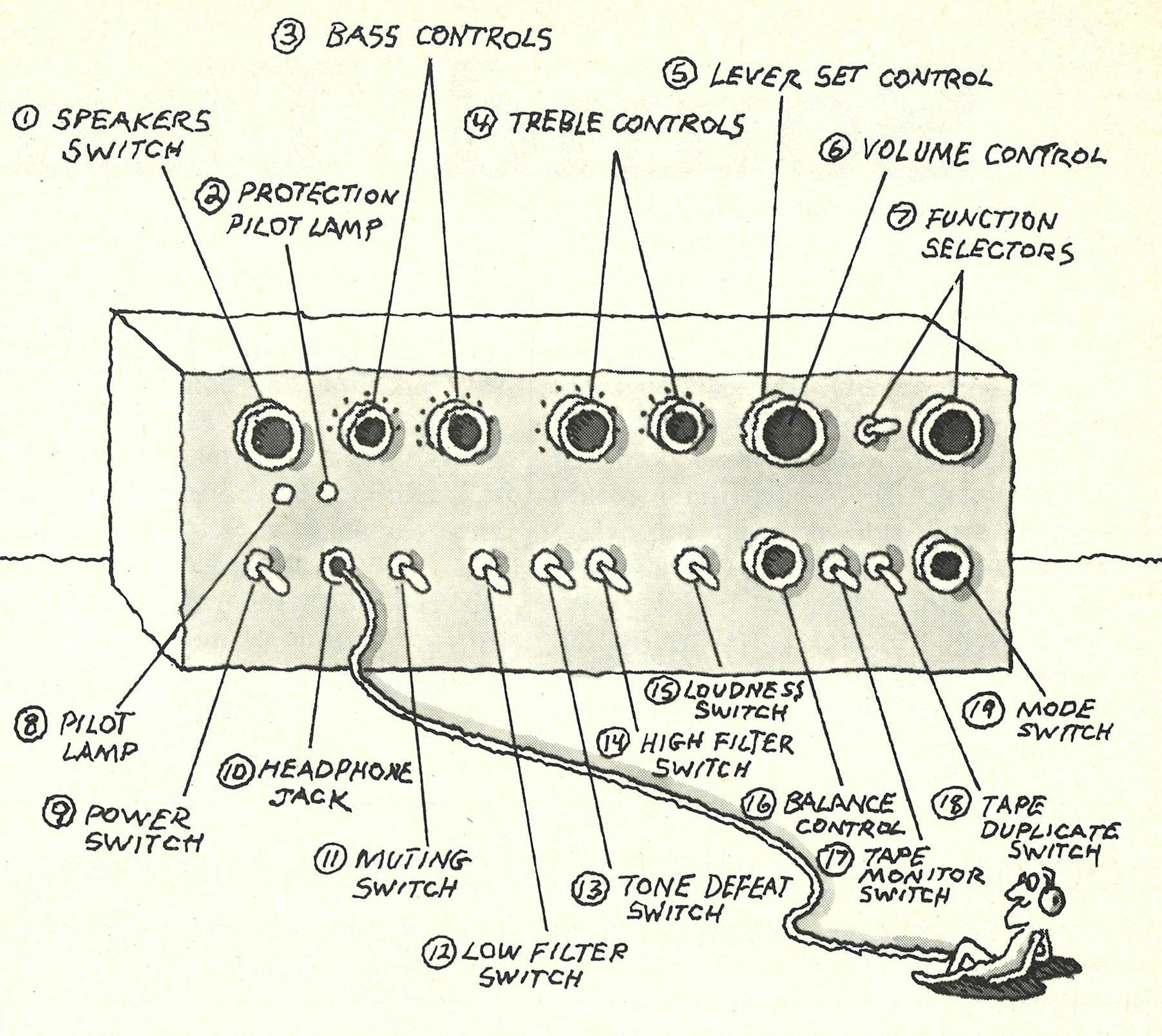

While power output rises with the retail cost of receivers and amplifiers, so do the number of controls and adjustment features. Front panels can appear quite complex to the uninitiated but each control and switch serves a purpose. While some listeners favor a minimum of control complexity, others want the fine degree of sonic tailoring made possible by the variety of knobs and switches found on costlier components. An example of an elaborate amplifier control panel is diagramed here, along with a brief description of the function of the more or less obvious operating knobs and switches.

The excellent monophonic or single-channel sound of the 1950s gave way to the improved stereo of the 1960s which, in turn, seems destined to give way to the four-channel sound of the 1970s. Aside from such major system developments, specific efforts are being made to reduce residual noise to the vanishing point and to increase the dynamic range of reproduced music until it is the equal of that heard at a live performance. Vacuum-tube equipment gave way to solid-state or transistorized equipment which is, in turn, being replaced in part by tiny integrated circuits (the same kind of miniaturized circuits that generated the entirely new electronic-calculator industry in just a few years). For all these advances, the component approach to high fidelity retains a non-obsolescent quality which permits additions to be made to your system without negating costly original investments.

SHOPPING FOR A SYSTEM

All sorts of retail stores and mail-order companies sell high-fidelity equipment. If you have previously listened to and have mentally selected the components of your choice, there’s nothing wrong with purchasing the entire lot from a mail-order firm or from an off-the-shelf discount type of store. Often, these types of outlets will offer high discounts on all but certain price-fixed or “fair traded” products.

Generally, such stores do not offer any service or warranty, so if something does go wrong during the initial period of use (or, if a component is inoperative when installed), you will have to depend exclusively upon the manufacturer’s warranty. In recent years, as the reliability of solid-state equipment has increased, manufacturers’ warranties have become increasingly liberal. While warranty periods still vary greatly within the audio industry, it is no longer unusual to find extended warranties lasting two, three, and, in some cases, five years on some products. But all warranties aren’t alike. While some manufacturers include parts and labor in their warranty arrangements, others guarantee replacement only, charging for labor or shipping costs. Regardless of the terms of the warranty, it’s important to fill out the warranty card and mail it promptly to the manufacturer—even if your dealer offers an over-the-counter exchange for defective equipment.

Unless you buy models and brands you are familiar with, be wary of small general appliance shops. While many shops that deal in refrigerators, air conditioners, and small electrical appliances often feature so-called “hi-fi” systems, they are usually inexpensive, poor-quality “compact” systems which are a far cry from true high-fidelity components. Some large department stores have separate high-fidelity departments, usually identifiable by the fact that separate sound listening rooms are used for selling this equipment. Such departments within departments will usually be staffed by personnel who are prepared to discuss your hi-fi needs and to spend a fair amount of time with you as you make your selections.

There are also the chains of audio specialty shops which deal only in hi-fi equipment. Some electronic stores also publish catalogs and cater to all sorts of electronic hobbyists, kit builders, and audio buffs. Finally there are the owner-operated hi-fi salons dedicated to selling hi-fi equipment on a person-to-person basis. The more specialized the operation the more individualized service you are likely to encounter and the lower the discount you will be offered for the components of your choice.

Before selecting a shop to audition components, make certain that the store stocks at least six major brands of each type of component, such as tuners, amplifiers, receivers, and speakers. There are more than one hundred manufacturers offering hi-fi speaker systems alone, but a half dozen brands, each with models in various price categories, should be ample for an intelligent selection.

Since it is possible to spend as little as $400 or as much as $10,000 for a good component system, a salesman needs some guidelines. A good salesman will also ask about your listening habits, the sort of music you favor, the room size, and your plans for adding speakers at a second location in the future. If he fails to ask these questions, volunteer the information.

Many dealers put together “package systems” consisting of receivers, speakers, turntable, and cartridge made by different manufacturers but offered at a single, package price. Often, this price is considerably lower than the sum of the prices of the individual components included in the “package.” For the totally inexperienced shopper, these systems are often worth considering. Their one weak link may be the loudspeaker system, since many dealers have speaker systems made for them, under their own “house brand” name. If properly designed, such speaker systems may well offer overall savings in cost, but more often than not they represent the “blind item” in the system and, if constructed of poor materials, provide the needed leverage for the low cost of the entire system. There is no way to guard against this practice other than to listen carefully to the speaker systems, comparing them with well-known brands.

In today’s hi-fi market, $400 is the very least you can expect to pay for a good hi-fi component system. At that price, you may have to content yourself with an integrated amplifier, a record player, and a pair of speaker systems, holding off on the purchase of an AM/FM stereo tuner component. A solid, middle-priced system will range anywhere from $500 to $1000. There is a tremendous variety of components available in this range.

It is, of course, not necessary to buy everything at once, though for stereo sound you will need two speakers and at least one program source to get started. If FM radio appeals to you, you can start with just three components: a good stereo receiver and two speakers. You can always add a record player later—or a tape deck, either open reel or cassette.

Without a doubt, the loudspeaker system is the great variable and the component that should be selected before any other. The only component you will hear is the loudspeaker (unless you are addicted to headphone listening). Each speaker produces a sound of its own. The idea is to choose that speaker with in your allotted price range that most nearly sounds right to you. To compare speakers, use recorded material with which you are familiar, preferably a recording you have played on a super system that you’ve admired. Listen to speaker systems in pairs, arriving at your final choice by a process of elimination. It’s a good idea to audition a few sets of speakers costing more than you plan to spend to get an idea of the difference in sounds.

In addition to the great variation in sonic qualities of speaker systems, there is a wide range in their relative efficiencies. Low-efficiency speakers (usually the smaller bookshelf varieties featuring fully sealed enclosures) may convert only one per cent or less of the electrical power fed to them from the amplifier or receiver into acoustic or sound power. High-efficiency models (typically, floor-standing bass-reflex or ported designs, large “infinite baffle designs,” and “folded horn” designs) may be able to convert from three per cent to ten per cent of the electrical energy fed to them. Only by first selecting speaker systems can you hope to make a proper choice of amplifier. A ten-watt-per-channel amplifier driving a high efficiency speaker system can produce the same sound volume as a 50- or 100-watt-per-channel amplifier connected to a very low-efficiency system. Selecting an amplifier or receiver that delivers more power than a speaker system can handle is a mistake, since speakers are not indestructible and can be damaged by being fed a sudden burst of audio power which exceeds their capacity.

Most audio specialty stores will unpack each component and test it for you before you leave the store. Many will offer to interconnect your entire system to make sure it all works together. Others are staffed with service technicians who, for a small charge, will visit your home to make sure you have installed the components correctly. Some stores will do this interconnecting for you, though the job is really quite simple and owner’s manuals supplied with equipment are full of information designed to make system connection foolproof.

Remember, audio components are sold on the basis of “one-step” distribution. The manufacturer sells his products directly to the retailer. There are no “middle-men” so that, in a sense, you are already ahead of the game in terms of the price you pay. Most audio dealers work on a potential mark-up of 35 per cent to 40 per cent. The discounts you can expect to get on hi-fi components are directly related to the amount of service provided. Obviously, the dealer who simply delivers your chosen components in sealed cartons “off the shelf” and is poorly staffed and ill-equipped to demonstrate the equipment in proper listening rooms may offer a greater discount than his competitor who has trained personnel, properly furnished listening rooms, and offers a variety of additional services.

GET IT ON TAPE

After records and FM radio, the most popular musical program source is recorded tape. As far as the hi-fi buff is concerned, tape offers a degree of involvement in sound and music that cannot be duplicated by either records or radio. With tape, you can create your own musical programs from live sources, from records, or from FM broadcasts. You can edit, excerpt, modify, and compile your own tape library. Recorded tapes last almost indefinitely and don’t lose their fidelity or become worn and noisy with repeated playings. When you tire of a tape recording, you can erase the music and use the tape over and over again.

The first tape recorders sold to consumers were open-reel machines. These come closest in performance and features to professional tape equipment used in recording studios for making master recordings. While professional studio machines transport the tape at fifteen inches per second (ips), most home machines offer a choice of slower speeds such as 7½ ips or 3¾ ips. Commercially available recorded open-reel tapes are duplicated at the intermediate speed of 7½ ips, a speed adequate to reproduce full frequency response in well designed open-reel machines.

The popular cassette tape format represents a great many technological breakthroughs. When you consider that the tape, encased in a dual reel cassette package, travels at the very slow speed of 1(7/8) ips, is only a bit over (1/8) inch wide, and can contain as many as four tracks (for stereo programs recorded on each “side”), it is truly miraculous that wide frequency response can be obtained from such cassettes. With all things being equal, the open-reel machine still has better potential for hi-fi results; but all things are not equal and special new tape formulations (notably chromium dioxide), noise reduction circuitry such as Dolby, and advances in cassette tape heads have made the cassette deck a most popular component program source.

By all rights, the continuous-loop eight-track tape cartridge should be able to provide higher fidelity and lower noise than the cassette. Tape is transported at a higher speed and is a full quarter inch wide like open-reel tape. As a practical matter, however, the cartridge format has several disadvantages: since the cartridge employs a continuous loop of tape, it is impossible to rewind an eight-track cartridge. Even “fast forward” motion intended to permit locating a given recorded selection is fairly slow. Most eight-track tape decks are limited to playback only, and pre-recorded cartridges are mass produced at speeds with limited fidelity and a fairly high amount of tape hiss or noise. While ideally suited for use in automobiles (the tape hiss is masked by road and wind noises), the eight-track tape format has not caught on as a home hi-fi program source.

While recorded tapes should last indefinitely, their preservation can be prolonged by storing them in moderate temperature and humidity environments. Professionals store tapes in the non-rewound position (“tail out” as it is called). Fast rewinding of open-reel tapes tends to produce a tighter wind of the layers of tape and can lead to a condition called “print through.” With cassettes, there is really no reason to rewind in the fast mode, after playing only one side.

It is extremely important that tape head surfaces and other points traversed by tapes be kept clean and smooth. Ferric oxide tends to be deposited on these surfaces after even a few hours of use. Ordinary denatured alcohol applied to a cotton swab dissolves this material readily, or you can purchase impregnated rolls of cloth tape which can be run through the recorder to perform the cleaning operation. Head cleaning is as important for cassette machines as it is for open-reel decks.

Residual tape hiss or noise consists primarily of high-frequency disturbances. If you listen to tape that is audibly “hissy” and turn down your treble tone control, the hiss disappears almost completely—but so does the high-frequency content of the music in the recording. The Dolby noise reduction system can greatly reduce the audible noise heard from recorded tapes without affecting the tonal response of the music.

The Dolby system cannot remove noise already present in program sources (records with loud surface noise). It can reduce the noise normally added to tapes during the recording process.

Principles of the Dolby process are now being applied to FM broadcasting too, since the background noise heard when weak FM signals are received is very much akin to the kind of high-frequency noise heard from “hissy” tapes. Some cassette machines equipped with Dolby processors can be used for listening to such Dolby FM stereo broadcasts as well. Such decks will have a switch position labeled “FM Dolby Copy.”

FROM STEREO TO QUAD

The growth of four-channel sound seems somewhat disappointing. As recently as two years ago, industry experts were confidently predicting that four-channel equipment and records would dominate the audio marketplace by 1975. Instead, four-channel sound took only fifteen per cent of the hi-fi component purchases of 1974. Nevertheless, when one considers the somewhat chaotic development of this new kind of hi-fi listening, not to mention the higher cost of quadraphonic equipment, the figures suggest an eventual transition to four-channel sound similar to the transition from monophonic, to stereophonic sound in the 1960s.

Contrary to one popular misconception, four-channel sound is not a replacement for stereo, but an enhancement which increases musical enjoyment in much the same way that a stereo tape deck doesn’t replace a record turntable, but does make the system more versatile.

When stereo discs were introduced in the late 1950s recorded sound lost its “pinhole” effect—the impression of originating from a single spot in the listening room—and spread out along an entire wall. If stereo sound added a second dimension, four-channel sound makes the next logical step with the addition of a third dimension—depth—and the creation of a total music environment. When you hear it for the first time, properly demonstrated, it is hard to believe that the effect is produced with only a record player or a tape deck, a four-channel amplifier or receiver, and four loudspeakers.

While industry experts continue to debate the merits of various four-channel recording techniques, the basic equipment needed to reproduce sound in four-channel can be clearly defined. Obviously four separate channels of amplification are needed. Owners of stereo systems are already equipped with two of the needed channels. A second stereo amplifier can easily be added to such systems, as can the extra pair of loudspeakers needed in any four-channel setup. Typically, speakers are positioned in the listening room with two in front and two behind the listener, but there are no hard and fast rules about this.

If tape, rather than records, were the most popular source of stored music, the transition from stereo to quad might be much further along; eight-track cartridge tape players lend themselves to four-channel sound recording quite easily.

In eight-track stereo cartridges, four programs are recorded on the tape, each using two of the available eight recording tracks. In the case of four-channel cartridges, two programs, each utilizing four of the available tracks, are recorded; suitable eight-track players or “decks” are now on the market—many of them equipped with automatic switching facilities for stereo playback as well. The four output signals from such decks need simply be connected to the four inputs on the amplifiers and a ready source of four-channel programming is available.

The library of pre-recorded Q-8 cartridges grows monthly. Unfortunately, the cartridge format was never regarded by serious hi-fi buffs as being capable of high-quality, hiss-free, faithful musical reproduction.

Open-reel tape decks, on the other hand, can and do provide excellent fidelity whether used to record and play stereo or four-channel sound. While the dedicated audiophile leans toward this program source, good four-channel open-reel tape decks are quite expensive and virtually no pre-recorded four-channel music is available on open-reel tapes. To build up a library, you’d have to tape existing quad records or broadcasts.

The first phonograph records developed and released to play four-channel sounds were known as “matrixed” records. Since a record groove has two walls, stereo programs can be inscribed on these walls readily—the “left channel” on one wall, the “right channel” on the other. In the case of four-channel music, what seemed at first like an insurmountable problem of squeezing four different signals into two available spaces was solved by combining the four signals electronically into two double or “encoded” signals and treating the two resulting encoded signals as if they were the two conventional stereo channels of an ordinary record. Thus, “matrixed” records are produced in very much the same way as ordinary two-channel discs and can be played using a conventional stereo phonograph pick-up. Many progressive FM stations throughout the country now devote a substantial part of their “on-the-air” time to the playing of such matrix-encoded records.

In order to unscramble quadraphonic broadcasts or recover the four available signals from matrix encoded discs, you must pass the two available signals through some form of decoder which extracts four separate signals from the broadcast or disc.

The newer quadraphonic receivers and amplifiers have the necessary decoder circuitry built in. Since “matrixing” offers a variety of schemes for combining and separating the four original program signals of a quadraphonic program, it is not surprising that different recording companies selected different matrixing techniques for their products. CBS Records developed a matrix system which it calls “SQ.” In Japan, the Sansui Company developed a somewhat different matrixing technique which it named “QS.”

Manufacturers have raced to keep up with the many variations and today you will find two or more switch positions on most quadraphonic components which enable you to select the proper decoding parameters for the different kinds of matrix discs now issued. Even in the absence of such switching, just, about any matrix decoder circuit will produce a very creditable four-channel effect when applied to any one of the several kinds of matrix discs now available. There is no reason to expect that one or the other of these matrix formats will dominate the field within the foreseeable future.

One very pleasurable bonus of the matrix disc idea arises from the fact that even ordinary stereo discs, however long ago they were recorded, contain varying amounts of “four-channel information” within their grooves. Just about any stereo record played through a matrix decoder and over the four loudspeakers of a quadraphonic component system produces a four-channel effect that many listeners find enjoyable.

It should be noted too that all matrix records are perfectly compatible with existing stereo playback equipment. Such records played on a two-channel system will simply combine the sounds of front and back channels into the two available front channels, with no musical content missing.

In converting from a stereo system to four-channel, the separately available matrix decoder serves to “tie together” the existing receiver or amplifier with the required second amplifier and added loudspeaker. Since most high-fidelity component receivers or amplifiers are equipped with a break-in point known as “tape monitor” jacks, tying in the new components to the old systems takes just a few moments.

While CBS Records and other recording companies were busily turning out matrix four-channel records, RCA and its Japanese affiliate JVC worked on still another approach to cramming four separate signals into the single groove of a phonograph disc. Utilizing principles borrowed from FM radio technology, they devised a system whereby super-audible high-frequency signals could be inscribed in the groove along with lower, audible musical frequencies. This system of recording is commonly referred to as the CD-4 system and records produced using this technique are alternately called CD-4 or Quadradiscs.

While these discs, too, are fully compatible with stereo playback equipment (again, front and back channels are heard through the appropriate front speaker of a two-channel system), in order to reproduce them quadraphonically a new form of unscrambling circuit, known as a demodulator, is required. This device fits between the phono pickup and the amplifier or receiver of your hi-fi system.

The prospective purchaser of a new four-channel component system need not be overly concerned with this extra requirement, however, since this new circuit is fast becoming standard equipment in current models of four-channel receivers and amplifiers. Because the new Quadradiscs contain very high frequencies, it’s necessary to play them with a new kind of pick or phono cartridge.

To date, there is no way to play the new CD-4 discs over FM radio. Currently the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and an industry committee are testing at least six systems that have been proposed for broadcasting four separate program channels over a single FM station, much as the two stereo channels of stereo program sources are now transmitted.

While audio experts continue to favor either the Columbia and Sansui matrix approach or the RCA discrete approach to four-channel disc recording, it is clear that both systems will continue to exist, side by side, at least in the foreseeable future. The modern quadraphonic receiver or amplifier incorporates all the circuitry necessary for both matrix and discrete disc reproduction. Given the premise that any four-channel music system needs four amplifying channels and four loudspeakers, the inclusion of two kinds of decoding circuits represents but a small percentage in the total cost of quadraphonic equipment and serves as a form of insurance to today’s purchaser that he will be able to play four-channel records in the future, even if one or the other system becomes dominant.

- More About:

- Music