Martin Tuley used a pistol to hijack a gas station when he was 18. Joe Torres committed robbery by assault at 25 and has been locked up since 1967. Fred Burke was convicted of killing his wife ten years ago. Gary Hart was convicted of trying to rape a police lieutenant’s wife. These four men have two things in common: they are all inmates in the Texas Department of Corrections, serving 199 years between them, and they are all rodeo clowns. For five Sundays a year, they dress in funny costumes and do things they hope will distract rough stock from fallen riders. They are part of what is billed as “The Roughest Rodeo Behind Bars,” which is one of the three things the Texas prison system does that attract public attention. The other two are quelling riots and electrocuting people, so it is small wonder that the TDC would rather talk about the rodeo.

Part spectacle (it drew 80,000 last year), part business (it cleared $200,000), and part public relations (no other state agency can approach the TDC’s hypersensitivity about publicity), the Texas Prison Rodeo bears about the same relationship to the serious business of the prisons that a football game bears to higher education: none. Yet, though it may seem an unlikely sponsor for a rodeo, the TDC has held one every Sunday in October since 1931. Its Huntsville Unit looks exactly as the movies have taught us a prison should look—fortresslike, dark, and forbidding. “The Walls” that give the prison its popular name are thirty feet high, solid brick, and ivy-covered on the outside. There are guard towers and searchlights at the corners and catwalks paced by uniformed men with automatic weapons. Only a city block in area, though it seems larger, the prison squats 300 yards east of the Huntsville town square and Waller County courthouse like an architectural monument to the metaphysics of nineteenth-century criminology: evil can neither be created nor destroyed; it can only be contained.

The permanent rodeo arena is located just adjacent to and behind The Walls and is not easily visible from the street that runs along the front of the prison. Although the main event does not begin until two in the afternoon, the crowd begins to mill around in the street in front of the prison as early as 8:30 a.m., sampling the amusements offered in the modest midway set up there. An inmate country and western band with an ethnic and racial composition that might have been determined by HEW guidelines plays more loudly than well, while an alternate band from another TDC unit sits in folding chairs onstage, huddled close and breathing into their hands against the unseasonal early-morning cold. Ten or more armed prison guards wearing heavy jackets stand in a group. The stage is a raised platform deep in the shadow of the prison wall with a brightly painted, two-dimensional scale model of the classic cowboy movie set—general store, bank, dance hall, and jail—as a backdrop. There are a lot of country music songs about prisons, but the band doesn’t play any; perhaps it has been ordered not to. Maybe somebody in the Texas Department of Corrections has heard the live album Johnny Cash recorded at Folsom Prison in California before he got religion and a network TV show. When he sang the line in “Folsom Prison Blues” that goes “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” the audience gave out a blood-curdling whoop that has made that version of the song a classic. Nothing like that happens at the Texas Prison Rodeo, but the audience nevertheless keeps a respectful distance from the stage, with hardly anyone venturing closer than five yards to a roped-off area just in front.

Across the street some people are standing in line for tickets. Others are paying 25 cents for black coffee (neither cream nor sugar is available) at stands set up on the grass by sorority girls from nearby Sam Houston State University. Later they will be able to buy dry hamburgers at the same stands for $1.60. But nobody complains. The crowd is as varied and good-natured as people at a county fair, which the street somewhat resembles. Getting ripped off in small ways is part of the fun. For a laugh you can buy a wanted poster with your own or anybody else’s name on it—Printed While U-Wait. There are quite a few takers. Others browse through a display of paintings and drawings by inmates—nothing for sale over $25, most cheaper than that. Purchases made there seem impulsive and more likely to be lost or thrown away than hung anywhere: bucolic free-world landscapes, sweethearts, inspirational slogans, hearts and doves in cages, and numerous portraits of Jesus.

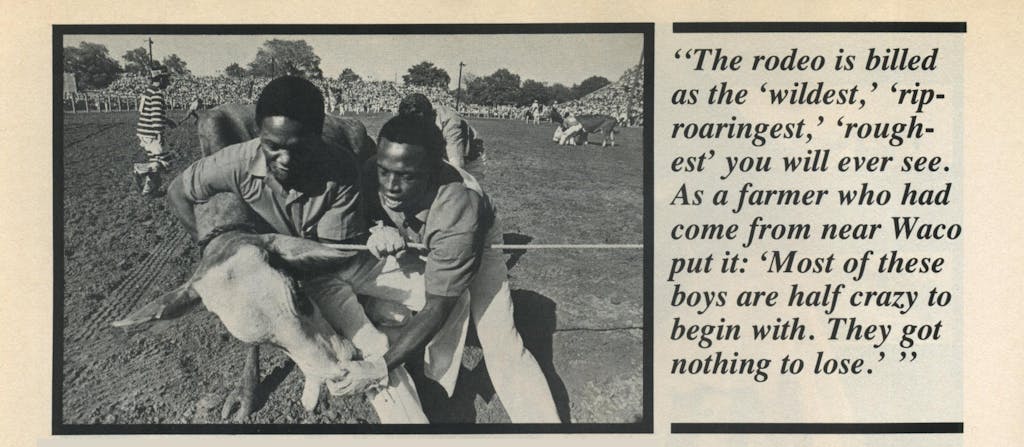

For the most part the Prison Rodeo seems to be a family outing, and although Huntsville is only seventy miles north of Houston, the crowd has a rural and small-town feel. Most of the people I met were from places like Navasota, Crockett, or Hearne. They had the casual friendliness of a group that has come together to have its prejudices confirmed, and since those prejudices, like the Prison Rodeo itself, are a holdover from what the sentimental imagination remembers as simpler times, they seem almost benign. The rodeo is billed as the “wildest,” the “rip-roaringest,” and the “roughest” you ever will see, and four out of five persons standing in line for tickets can tell you why they think that is so. As a farmer who had come from near Waco to bring his grandson to the rodeo put it: “Most of these boys are half crazy to begin with. And they got nothing to lose.” The inmate cowboys don’t look at it that way, of course, nor do the spectators who come to see a friend or relative in the competition. But the TDC puts on its show for the others.

Children stare at the inmate trusties, set apart by their starched prison whites resembling bleached army fatigues, names stenciled in black over the breast pocket, as they circulate through the crowd hawking programs and record albums by the prison band. Adults appraise them more cautiously. There’s a mean-looking scoundrel. Wonder what he did? Don’t guess it can be too bad or they wouldn’t let him out here.

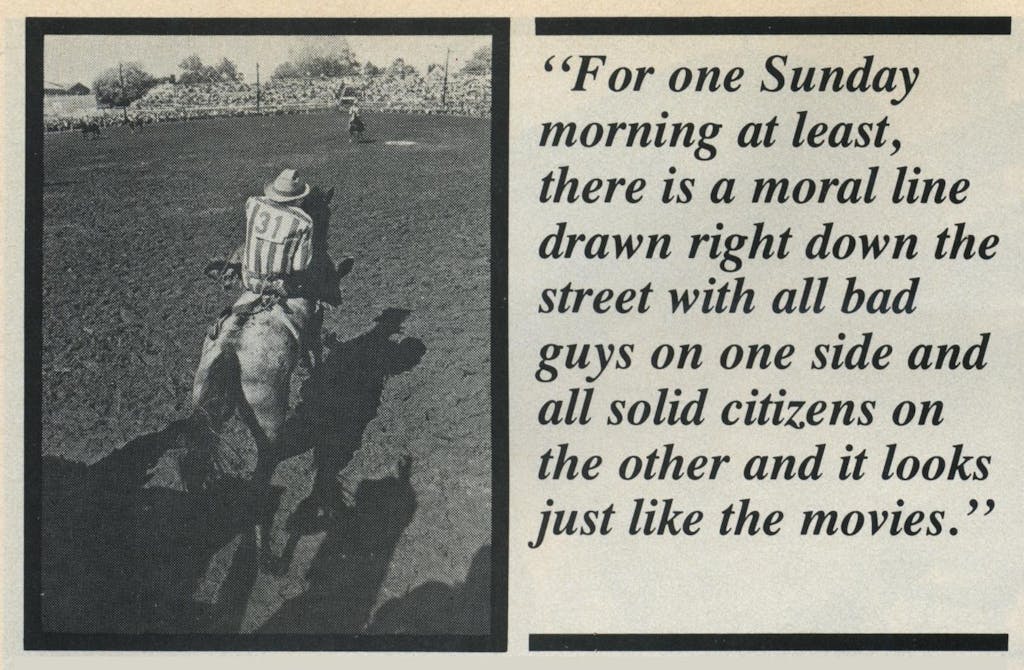

But it is The Walls that everybody has come to see. For one Sunday morning at least, there is a moral line drawn right down the street with all bad guys on one side and all solid citizens on the other and it looks just like the movies.

Willie Craig is not from The Walls but stays twenty miles north of Huntsville in the maximum-security Ellis Unit, which is supposed to be where they keep the real badasses. Death row is at Ellis, although the chair itself—“Old Sparky” they call it—is at The Walls. Despite its melodramatic architecture The Walls is a medium-security facility and said to be a much easier place to do time than Ellis, which incorporates the most up-to-date features for controlling recalcitrant men in groups. The cell blocks at Ellis are strung out along a central hall which can be shut off at many points to isolate sectors in the event of trouble—very much like, on a larger scale, the way that rodeo animals are run into chutes and kept there. Instead of a wall, there are two chain-link fences, one outside the other, with large rolls of barbed wire filling the fifteen feet of no-man’s-land in between. Electronic sensors buried in the ground near the perimeter of the inside fence can detect vibrations made by human feet and flash a warning to the guard towers.

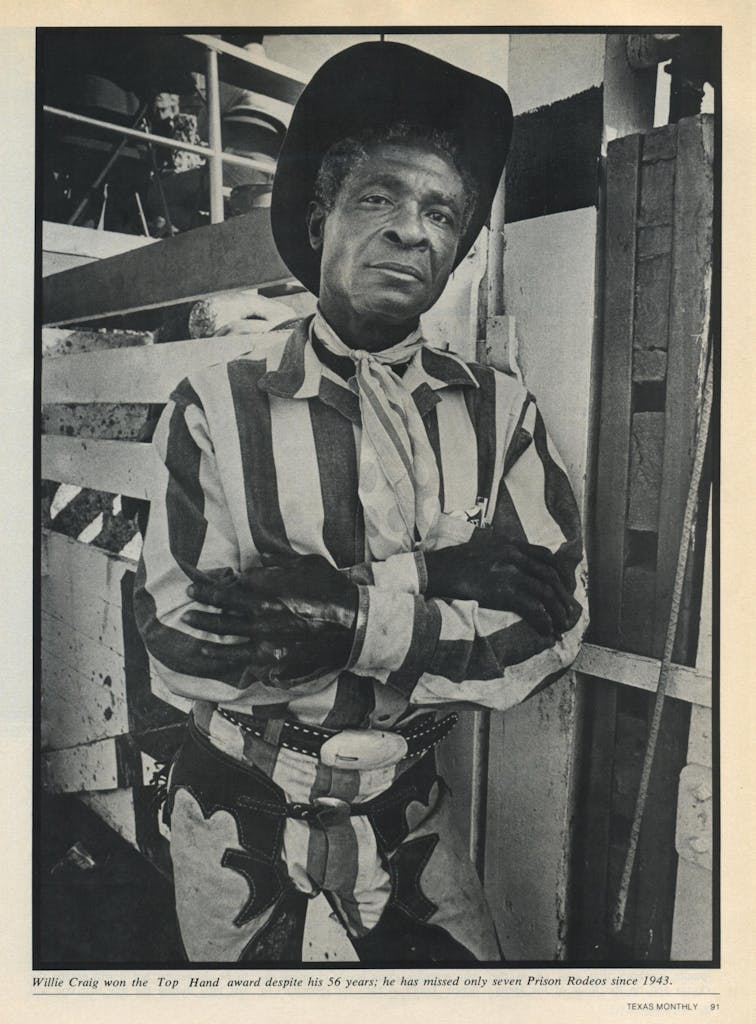

According to prison records and his own recollections, Willie Craig was born in 1921 and is 56 years old. Some think he is older. Like many rural Southern blacks of his generation—he is from Leon County in East Texas—Craig was not born in a hospital and has no birth certificate. When an official of the Prison Rodeo heard I was planning to inteinterview Craig, he said: “You tell Willie I said I’ve known him for fifty years myself, and he was full grown when I met him.” After I did, Craig inhaled on a cigarette and smiled a tight smile. “I come down here first on July 10, 1943.” It is not the sort of fact a man is likely to forget.

Because of World War II there was no Texas Prison Rodeo in 1943, the only year since its founding that it has been cancelled. The next year it was held as a “Victory Rodeo” and the profits invested in war bonds. Willie Craig rode in it that year, though it was not his first rodeo—he had been allowed to be a clown in the segregated rodeos of his youth, thanks to the intercession of the white owner of the farm on which he was raised. Since then Willie has missed only seven Prison Rodeos, during the brief intervals when he was not behind bars. He has either served or been paroled from five sentences, ranging from two to forty years, the most recent conviction being for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, performed at the age of fifty. Craig says that he was last paroled in the care of a man who employed him as a farm laborer but paid him only $5 a day for his work, subtracting Social Security from that and leaving him barely enough to buy food and pay the electric bill for the housing he was furnished. He next comes up for parole in 1980, and should it not be granted he expects to die in prison. “I won’t live long enough,” he says, “to do no thirty years.”

At the moment he seems anything but moribund. If there were such a thing as a 56-year-old Marine PFC, Willie could model for a recruiting poster. He holds himself erect with a bearing that is almost military; when he talks, he looks people square in the face with a steady expression that stops just this side of challenge. No doubt that look has landed Craig in trouble more than once. Repeat offenders are not usually assigned to units on the basis of their crimes, but on their characteristics as prisoners, and Craig’s record shows a history of fighting other inmates, cursing guards, and “insolence.” Given the conditions prevalent in Texas prisons through the forties, when they are conceded by current TDC officials to have been among the worst in the nation, a record like that is hard to evaluate. Now he seems to have mellowed somewhat and talks about wanting to be able to talk to groups of young men to warn them against wasting their lives as he believes he has done. It is the kind of talk you hear often when talking to inmates, and it is impossible to tell whether he believes it or expects his listener to. Like all prisoners, he wants out.

More than one prison official hypothesized that Craig’s desire to return to the free world is an illusion, that his long years in jail have left him what penologists call “institutionalized”—so adapted to the secure rigidity of life as an inmate that he is actually happier and more successful on the inside than he could ever be with the uncertainties of civilian life. Whether or not that is true, Willie has a prison job that suits him well and helps keep him in good shape for the rodeo. He is a “dog boy,” a trusty who cares for and trains the Ellis Unit’s bloodhound pack. Much of every working day he is on horseback, laying scent trails and then riding with the dogs to track them down. The job separates him somewhat from other inmates, a contingency that seems to suit him. On the Saturday morning I talked to him, Willie had to be summoned from the fields, where he and some prison employees were using a pack of dogs to hunt herds of feral pigs that feed on the prison corn crop.

Bemused by what is presented as a cross between gladiatorial spectacle and Keystone Kops buffoonery, the ticketbuying public is only intermittently aware of the intense rivalry among the inmate cowboys that goes on in the chutes and on the floor of the arena. But a cumulative account is kept of the money winners in the three individual riding events—bareback, saddle broncs, and bull riding—and the overall leader at the end of each year is designated “Top Hand” and presented a silver belt buckle as a prize. Trophy buckles are also given the overall winner in each of the three events. After the first three Sundays of the 1976 rodeo, Willie Craig had an all but insurmountable lead in the saddle bronc event and stood a close second in the all-around standings for Top Hand. In his 25 appearances in the rodeo Craig had never finished first overall, although he had been second in 1970 and almost as close several times. Just ahead of him was a tobacco-chewing cowboy from the Eastham Unit named Johnny White, and, for reasons neither of them will discuss, Craig and White do not like each other at all. Willie saw a chance to apply some pressure. “You watch the horse I draw in the saddle broncs,” he told me. “You can tell them if I get Cowchip or Reckless Red to ride these last two weeks, I believe I’ll win. I’ll get the all-around and the saddle bronc. At my age that’s going to shake them all up. Sure will.”

Just before the gates to the arena are opened, guards rope off a section of the street in front of The Walls and a phalanx of black men comes jive-stepping in cadence out of the prison like a platoon of Tontons Macoutes from Port-au-Prince. It is the Retrieve Unit Highrollers, a voluntary self-trained and self-selected drill team, and you can feel a mild thrill pass through the crowd when they first appear. These are some very bad-looking dudes, half of them in dark glasses and all wearing immaculate prison whites and black berets. They do precision close-order drill to the accompaniment of an inmate leader who marches along beside chanting cadence. Tradition calls for spectators to toss coins into the street and for the Highroller who first spots the money to perform a little buck-and-wing step, never breaking cadence, and to deposit said coin in his pocket. At this the cash begins to ring on the pavement in what seems a special celebration commemorating Jim Crow. The Highrollers are well trained and their show is a good one, but the scene is uncomfortably reminiscent of the Battle Royal in Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man. By the conclusion of the performance some of the Highrollers are abandoning cadence and scuttling out of formation to grab what they can get off the street. The symbolism seems too crude to be deliberate, but it will not be the last time during the day that one will realize how literally the Prison Rodeo teaches the few simple lessons it offers. You want that money, brother, you go scratch for it. But like everybody else who appears at the rodeo, the Highrollers are volunteers. Nobody makes them do it.

The real enthusiasts of the Prison Rodeo are the “convict cowboys” and inmate clowns, and Gary Hart is among the most enthusiastic of all. Hart has done more than nine years on a fifty-year sentence for assault with intent to rape, a crime he continues to insist he did not commit. Rapists are among the least popular offenders with their fellow inmates and the most likely to maintain their innocence, but Hart has pursued the issue far more zealously than most. Hart, who has done work toward a degree in psychology, was managing a Fort Worth supermarket ten years ago when he was arrested, he says, on the basis of a composite drawing, then picked out of a lineup by the victim as her assailant. He has passed three polygraph tests supporting his contention, but such tests are not admissible as evidence. Hart has long since inured himself to doing his time, that sad little understatement, and doing it as productively as possible. With “good time”—two days credit on his sentence for every day served with good behavior—he will be eligible to go before the parole board for the first time this winter. If it is granted he will either do graduate work in criminal psychology—he says the textbooks he reads on the subject sound like a combination of fairy tales and science-fiction stories—or pursue an avocation he learned only after coming to prison: being a rodeo clown. He is leaning toward the rodeo.

Regardless of the publicity and the expectations of heedless cowboy daring the Prison Rodeo may arouse among spectators, the one prerequisite an inmate must have even to come to the tryouts on the last two weekends in September is a perfect disciplinary record for the preceding six months. It is not easy to steer clear of trouble in a prison, and though Hart has managed, his course has not left him in good stead with other inmates. A preacher’s son, Hart during the work week is an assistant to the prison chaplain, the same job Fred Carrasco once held, and one not without its small freedoms. Also, he is one of a handful of inmates sent out to be interviewed by almost every reporter who visits the event. Inevitably, his favored position has aroused resentment. “Gary Hart is a real politician,” another cowboy told me, “what we call a ‘suck-ass.’ You’ll never hear him say anything negative.”

Hart is aware of sentiments like that, but he doesn’t think he can do anything about them: “Some guys in here think that by going out for rodeo I’m going along with the establishment—making money for the system. But some of them are so bitter they think if I go out and play baseball I’m doing it for the State.”

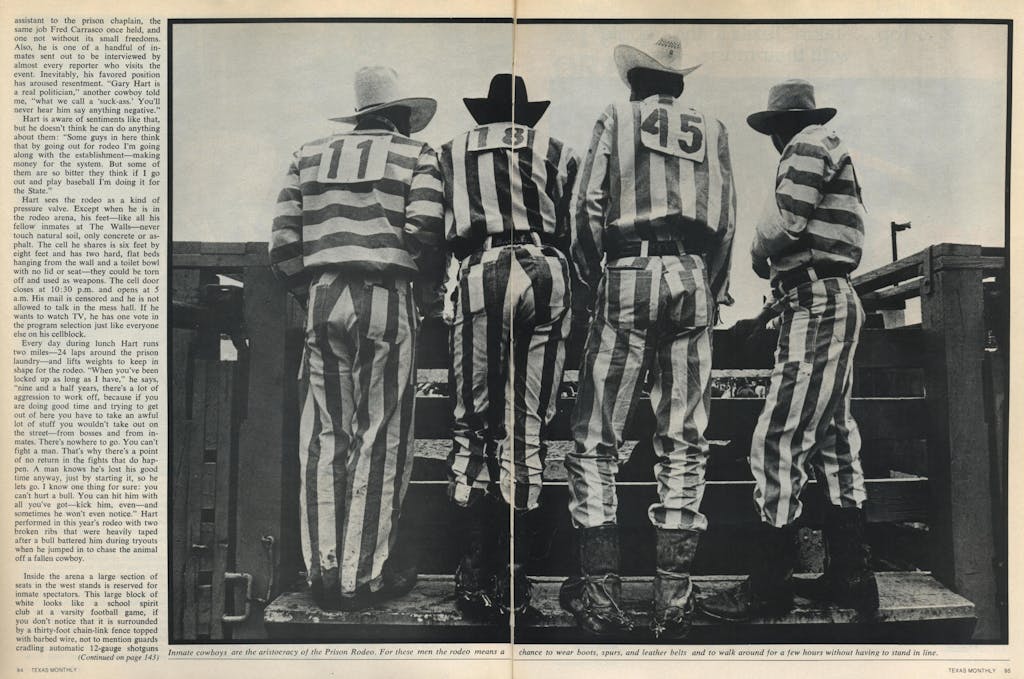

Hart sees the rodeo as a kind of pressure valve. Except when he is in the rodeo arena, his feet—like all his fellow inmates at The Walls—never touch natural soil, only concrete or asphalt. The cell he shares is six feet by eight feet and has two hard, flat beds hanging from the wall and a toilet bowl with no lid or seat—they could be torn off and used as weapons. The cell door closes at 10:30 p.m. and opens at 5 a.m. His mail is censored and he is not allowed to talk in the mess hall. If he wants to watch TV, he has one vote in the program selection just like everyone else on his cellblock.

Every day during lunch Hart runs two miles—24 laps around the prison laundry—and lifts weights to keep in shape for the rodeo. “When you’ve been locked up as long as I have,” he says, “nine and a half years, there’s a lot of aggression to work off, because if you are doing good time and trying to get out of here you have to take an awful lot of stuff you wouldn’t take out on the street—from bosses and from inmates. There’s nowhere to go. You can’t fight a man. That’s why there’s a point of no return in the fights that do happen. A man knows he’s lost his good time anyway, just by starting it, so he lets go. I know one thing for sure: you can’t hurt a bull. You can hit him with all you’ve got—kick him, even—and sometimes he won’t even notice.” Hart performed in this year’s rodeo with two broken ribs that were heavily taped after a bull battered him during tryouts when he jumped in to chase the animal off a fallen cowboy.

Inside the arena a large section of seats in the west stands is reserved for inmate spectators. This large block of white looks like a school spirit club at a varsity football game, if you don’t notice that it is surrounded by a thirty-foot chain-link fence topped with barbed wire, not to mention guards cradling automatic 12-gauge shotguns in their arms. Inmates are led in and out of the arena in single file through a narrow tunnel connecting with the prison just behind; it is a slow process and they must start filling their seats long before the festivities begin. Once they are in their assigned seats they may not leave for any reason until the rodeo is over, and as the rest of the crowd leaves, they slowly file back inside, to the accompaniment of the TDC Rodeo Band, located high over the south end of the arena in a caged-in bandstand.

For several reasons the rodeo is not especially popular inside, and the number of inmate spectators on the three Sundays I attended varied from a couple of thousand on the day Freddie Fender was the featured entertainer to fewer than 200 for the final show on a crisp, sunny, perfect autumn afternoon—a contingent easily outnumbered by the armed guards looking on. I asked a guard why there were so few. “Most of these guys,” he said, gesturing back toward the prison, “are pimps or hustlers—not all, but most. You don’t get many of what you’d call your real rednecks in here. They think the ones who do come out for rodeo are crazy.” Most inmates, statistically at least, have little reason to be interested in rodeo. Over 70 per cent of the 20,700 men and women currently incarcerated in Texas state prisons come from urban areas; 29.2 per cent are from Dallas alone, another 21.7 per cent from Houston. The Prison Rodeo once was a means of publicizing the system’s agricultural achievements—there used to be an exhibition of TDC livestock and the animals used in the competition were bred and trained by inmates as recently as 1964. Now they are rented.

There are three classes of competitors in the Prison Rodeo, brought in one group at a time and kept separate throughout: “redshirts,” “cowgirls,” and “convict cowboys.” Redshirts, so named because their jerseys are that color, which is popularly (and erroneously) thought to arouse indignation in bulls, participate in Hard Money, the event which, more than any other, gives the Prison Rodeo its unique character and convinces onlookers that they are watching desperate men who have nothing to lose and will risk anything.

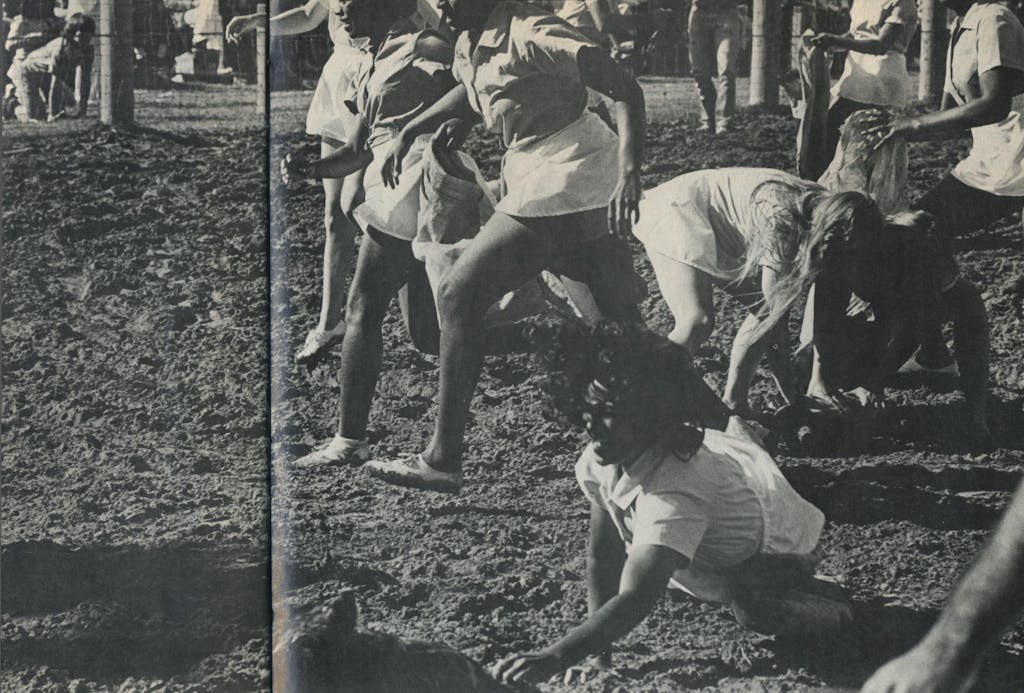

A Brahman bull is outfitted with a tobacco sack representing $25 or more between his horns; forty men go into the arena with him and try to take it off. The only rule is that it cannot be done from the fence. It is a good thing, perhaps, that bulls are color-blind and audiences are not. As for the cowgirls, most of them are no more rustic than their namesakes who dance on the sidelines at Dallas Cowboy games. Like the redshirts, they are mostly blacks or Chicanas from Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio, and also like the redshirts, they are in it mostly for the money. Not the prize money—the odds against them are too great—but the five bucks everybody gets who participates in or works for the show, even the trusties who were sent out after a Saturday rain this year to bail out the biggest mudholes with teacups. The women compete in two events, a greased pig sacking contest and a “calf tussle.” It is amazing to see how far a four-month-old calf with a rope around its neck can drag a woman on her face through the mud. The crowd eats it up. No cowgirl I met had ever touched a pig or cow anywhere outside a frying pan, nor would they once they got out of the slammer. The most experienced horsewoman of the group commented that “I’ve been on a horse—one time—but he better not move. If I got tossed like the dudes last week, I’d die in midair.” Except when they are performing in the arena, the redshirts and cowgirls sit in separate fenced enclosures not too far apart. But they may not speak to a member of the opposite sex, nor to the audience. So they exchange looks and the women cheer for the cowboys.

Many of the cowboys invite their families to watch them perform, but the cowgirls do not. The women give different reasons. Cynthia McCarthy of San Antonio says she wouldn’t want her mother to see her covered with dirt and messing with a bunch of pigs and cows. For her partner, Patricia Alvarado of Galveston, the restrictions placed upon the performers in the arena are too painful. She asked her husband not to bring her children, ages two and seven, to Huntsville on rodeo weekends. “It hurts too much to see them and not be able to get to them and touch them. They don’t understand and it would make them cry.”

Johnny White is an honest-to-God cowboy from Big Spring, doing six years of riding and roping at the Eastham Unit of the TDC for packing a pistol when he was on parole. At Eastham they call his job “stock boy” because “cowboy” seems too dignified, but that was one thing he did outside and that is what he does in jail. White is a stocky man with the forearms and grip of someone who has worked hard and hit things with his hands and a face that has been outside in the wind and inside in roadside honky-tonks and has been hit a time or two itself. He chews a big plug even when he is riding and he spits on the ground. He will talk for an hour trying to explain the finer points of style by which professional cowboys are judged but which nobody at the Prison Rodeo has the opportunity to practice, but if asked to talk about something he doesn’t want to discuss—like what it is between him and Willie Craig—he just closes up until somebody changes the subject. “I just don’t like him and he don’t like me. I ain’t gonna talk about it.”

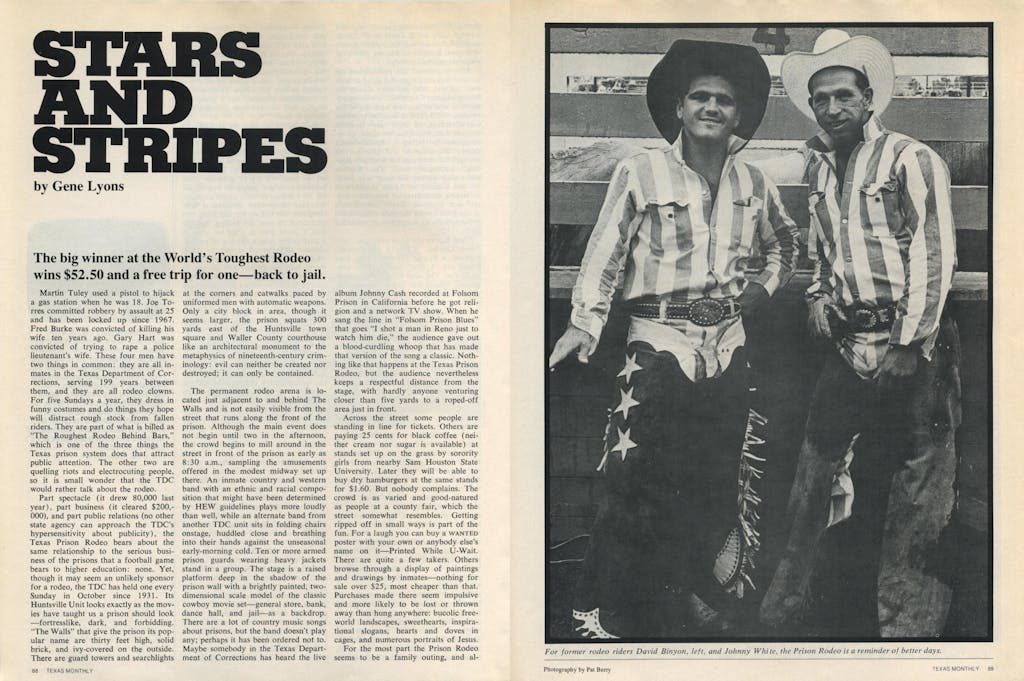

The cowboys carry themselves as if they are the aristocrats of the Prison Rodeo. For men like David Binyon of San Angelo, Don Washington of Palacios, Cleo McGrew of Edna, Henry Hinson of Josephine, Rusty Fluff of Pampa, for Johnny White and Willie Craig, all of whom rode competitively before coming here, it is a continuation of a way of life, a reminder of what they were at their best and what they would like to be once more. None of them especially likes being called a “convict cowboy”—they are “inmates” the rest of the year, “convict” being considered in correctional circles a backward term like “colored.” They all chafe at having to wear striped costumes just because the ticketbuying public expects convicts to wear stripes. The normal prison uniform, the only prison uniform, is white. In Texas stripes used to be worn on chain gangs by prisoners who had run. By now, though, stripes are the rodeo uniform just as knickers and high socks are part of a baseball uniform without anybody knowing or caring why. Unlike everybody else, the cowboys are permitted on those Sunday afternoons to wear boots, chaps, and spurs, ornate belts with trophy buckles if they have them, and cowboy hats.

There are things to be endured, such as the tasteless and heavy japes of arena announcer “Buffalo Bill” Bailey, on loan from Houston radio station KENR. Bailey likes to call for the cowgirls entering the arena for the pigsacking competition to wave across the field to the male inmates in the bleachers and tells the inmates to wave back. Then he comments to the effect that a wave is all any of them are going to get for twenty years. When it is Stanley Stillsmoking’s turn to ride, Bailey calls the full-blooded Indian from Browning, Montana, “the black sheep of the Blackfeet.” He has stuff like that written down in a notebook. Most of the inmates stand at attention with their hats off for the National Anthem, but when the band plays “Texas, Our Texas” and when Buffalo Bill reads Johnny Cash’s maudlin and tacky “Tattered Old Flag” as a banner is carried around the arena, most of them start scratching and spitting on the ground.

But they are out there in the sun standing on their own two feet for a whole afternoon with nobody to tell them to get in line and keep quiet. There is dirt and shit and a certain amount of healthy fear in the air and it makes them feel good. They know that they are gladiators and that the crowd half hopes to see their blood, but they know too that the crowd is fickle and will cheer them if they ride well. They are not supposed to talk to the girls or the spectators either, but the rules are often broken in small ways. Standing on top of a chute helping a buddy onto a bareback bronc, a cowboy mouths the words “I love you” to someone in the stands behind him. The next Sunday I asked him if he hadn’t been taking a chance. “Damn straight,” he answered, pointing. “My wife and kids was back up here and my girl was over there and didn’t neither of ’em know about the other.”

David Binyon begins and ends a conversation with a simple statement: “When I’m in the rodeo I’m in the free world.” Willie Craig, asked if it is worth the risk of an injury at his age for the chance of beating 27 competitors to a first prize of $52.50, thinks a moment. Then he says: “If they was paying nothing, I’d still ride them.”

Hard Money is the crowd’s favorite event, which is why it is staged twice, at the beginning and near the end of each performance. There are no tryouts for Hard Money; the redshirts just volunteer. Most have never been on the same side of a fence with a bull before, Gary Hart says, and the bluffing and boasting many are prone to try beforehand turns quickly to terror as they see that the animals not only weigh about as much as a Volkswagen, but also have faster acceleration and a shorter turning radius. So they jump over fences and scatter pell-mell while the crowd roars and laughs. The remaining handful of men who know something about animals, most of them clowns or cowboys, stalk them knowingly until the bulls are winded and confused, then dart in to snatch at the tobacco sack when they think it is safe. Other events are much more dangerous, Hart insists, because a man who knows bulls has a much better chance with them while on two feet than he might after being thrown to the ground dazed or hurt and is the only moving target in sight. Bulls are usually quite predictable, charge in a similar manner each time, and will jump over a man who throws himself under their front feet. Besides which, he says, they don’t have the pointed horns of the animals used in Mexico for bullfights; while bigger, they are not so quick. Being hit by one is no worse, say, than being hit by George Foreman. It will knock you flat and maybe break a couple of ribs, but it won’t kill you. Besides, Hart reminds me, “we don’t have to pay any medical bills you know.” It is true. The TDC is the purest form of socialism this side of the U.S. Army.

Rodeo clown Martin Tuley might have disagreed with Gary Hart about whether bulls are dangerous, except he was still in John Sealy Hospital in Galveston with serious chest injuries suffered two weeks earlier. A bull got Tuley down on the ground during Hard Money in the first performance of this year’s rodeo. The bull would have killed him, but fellow clowns Fred Burke and Joe Torres pulled it off him, and it’s a good thing they did it quickly, because Gary Hart was on his way with broken ribs taped so heavily he was moving as though his body were in a vise. These are the things they talk about in the chutes: Hart’s ribs, Tuley’s chest, Don Washington riding with his broken hand in a cast, habitual offender Bill Sheffield limping around on a cane because a bull stepped on his foot. Sheffield is sorry that his protégé Ricky Faith, a Viet Nam veteran doing ten years for sale of drugs and burglary, has broken his hand and cannot ride. The first time Faith ever rode a bucking horse was in the tryouts, after Sheffield and Johnny White had given him a lot of theoretical training. The third time he rode, Faith took second in saddle broncs, but now he is through for the year.

But nobody talks about Alex Baker. They don’t talk about Baker partly because nobody knew him very well. A 46-year-old inmate from Houston, Baker was serving a 15-year sentence for robbery by assault, and the tryout was his first. He was thrown high by a bronc, landed on the animal’s rump on the way down, and broke his neck when he hit the ground. He is expected to be a quadriplegic for the rest of his life.

Nobody in the TDC likes to talk about Baker either; he has become an unperson. His injury wasn’t reported outside the system, nor did news of it appear in the Echo, the carefully monitored inmate newspaper. Inmates slipped reporters the details like a nickel bag. There was no real need for such secrecy—such things happen in rodeos, and always will; Baker was a volunteer and signed a release absolving the TDC from responsibility—but when the TDC hushes up a sad but understandable accident like Baker’s, it’s hard not to wonder what else they’re concealing. It causes people to look twice at their other stories, from their recidivism rate, claimed to be near 30 per cent (most urbanized states are closer to 40 per cent—but TDC figures appear to be “soft,” not counting probationers or persons previously in federal or other state prisons), to the allocation of the $200,000 Prison Rodeo profits. (The money goes into the prisoners’ Education and Recreation Fund, which the TDC says is used for everything from constructing chapels and hiring chaplains and medical specialists to buying movies, books, magazines, eyeglasses, artificial limbs, and turkey dinners with all the trimmings on Thanksgiving and Christmas—all on less than $10 per inmate per year.)

As rodeos go, the Texas Prison Rodeo is not considered a good one by people who know. The usual reason given is that, since inmates cannot practice, the judges have to ignore the finer points of style in the riding events. But there is a deeper reason, one that makes the chemistry of the entire spectacle seem somehow out of balance, like watching a TV quiz show that one knows to be rigged. Although in form it mimics a contest of skills, it is, like so many others in contemporary culture, a pseudoevent; its true function lies in public relations. The TDC goes to great lengths to conceal the dignity and pride of accomplishment that athletics can bring. It is a prison rodeo, and the public is never allowed to forget that the location is more important than the event.

What one particularly misses as a spectator is the element of competition that gives structure and meaning to an athletic event. Riders come out of the chutes in the three skill events so quickly that there is no time to announce their scores, the standings in that event, or the overall leaders. Sometimes the audience is not told who has won a given event, and in any case the announcements are made hurriedly while something else is going on in the arena—except, interestingly, in the barrel riding competition, open only to non-inmates, where each girl’s mark is announced after her ride and before the next. The pace is very fast; the Hard Money bull is no sooner out of one end of the arena and the redshirts on their way back to their seats than wham! the first chute is opening and the bareback bronc riding is underway. When the last man has ridden in the first section of that event, the Goree Cowgirls are immediately escorted in, Buffalo Bill does his little routine, and the arena is filled with calves and women chasing them. Nobody in the crowd seems to mind.

The cowboys don’t really seem to mind either; they pay very little attention either to the audience or Buffalo Bill. But sometimes the sad ironies of prison life penetrate behind the chutes. On the next-to-last Sunday of the 1976 event some of the cowboys began to wonder whether someone had not decided that there were public relations benefits in having a 56-year-old black cowboy win the belt buckle for Top Hand and arranged that the judges should see things in his favor. Many say that Willie Craig committed a clear foul in the saddle bronc competition that day—grabbing the pommel with his free hand to avoid being thrown—and ought to have been disqualified. Instead, he was given first place, moving him within a few dollars of overtaking Johnny White. I saw the event, but I am no rodeo expert. It bears repeating that Willie Craig is not popular with most of the other cowboys and that Johnny White is. Also, a rodeo, even under these circumstances, is very difficult to fix.

I was told that on the last Sunday of the competition some of the cowboys would do what they could to see that the bias in Craig’s favor was balanced. In the second section, some said, Rusty Huff, who was so far ahead in winnings in that event that he had the buckle won, and who was being paroled the next day after serving nine years for bank robbery, would take a dive to give White a boost. While he was not thrown, Huff did not spur his mount and gave a lackluster ride. “No, I didn’t try real hard,” he told me. “I thought I’d give Johnny a chance.” But Johnny was thrown.

In the first section of the bareback event, Willie Craig was thrown hard and walked back to the chutes looking every minute of his 56 years. Craig and White both had good rides in saddle bronc riding, but Craig was placed third and White did not show. Craig was now the leader by a few dollars and there was only the bull riding to come. Both men were in the last section of the final event. If either could finish in one of the first three places ahead of the other he would be the Top Hand for 1976. In an ordinary rodeo it would have been a tense climax, particularly when Craig came out of the chute and was quickly thrown. But only a handful of people inside the arena were even aware such a contest was happening, least of all Buffalo Bill, who had lost his place in the program and announced Johnny White as Lloyd Lizakowski, complete with a crack about Polish cowboys. Before Buffalo Bill had time to correct himself, White had been dumped hard and his championship hopes ended.

Sitting in the dirt by the gate where he and his fellow cowboys were lining up, changing their boots for regulation black prison-made shoes, White hardly looked up as Willie Craig stood proudly in front of the announcer’s stand and accepted the buckle for Top Hand. Hardly anybody else watched either. Unaware of the dramatic moment that had passed, most of the crowd was on its way out the exits, hustling to beat the traffic out to IH45. White refused to take anything away from Craig’s victory. “They could’ve placed me in the saddle bronc, but they didn’t. I got throwed in the bulls all by myself. I had my chance, I just didn’t get it, that’s all.” Two fences and twenty yards away White’s parents were standing, having driven down from their home in Big Spring hoping to see him win. White’s father is a big raw-boned man who wore boots, a brown Western suit, and a cowboy hat, and he stood there with his wife hanging on his arm, saying nothing. Johnny looked around quickly to see if any bosses were looking and broke a rule by talking to his father. “He won it fair and square but I just give it to him.” He shook his head. “I just give it to him.” Then he got in line and followed the rest of the cowboys back inside.

White won’t be back. He completes his sentence this year and says he is going to move his parents to New Mexico because they are getting on and they need somebody to care for them. Gary Hart will talk to the Board of Pardons and Paroles before this is published and he hopes not to return either. Nobody ever comes back as a spectator.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Sports

- Prisons

- Longreads

- Huntsville