This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

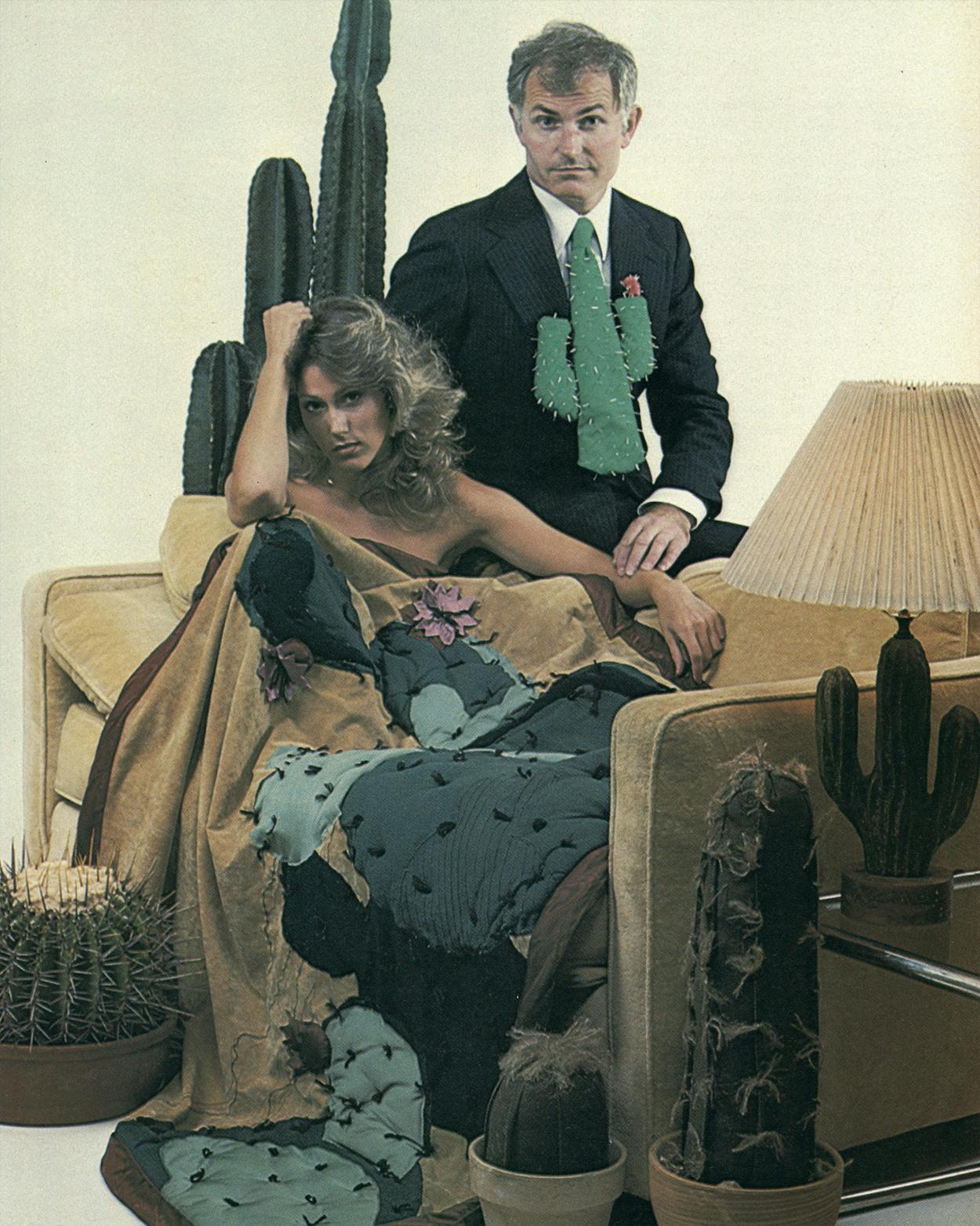

Of all the things calculated to summon an image of the wild West, nothing is as surefire as the sight of a cactus. Whether concealing the traditional rattlesnake or just sitting placidly potted in someone’s living room, a cactus usually prods the imaginations of red-blooded Texans to romantic visions of endless desert, big sunsets, and a simpler life. That may be why they’re becoming so popular.

Of course the current fascination with cactus isn’t the first one. After the discovery of cactus by Spanish expeditions to the New World in the fifteenth century, cactus chic ran rampant across Europe. By the early 1800s the exotic plant had become the plaything of the rich, with entire businesses thriving on its importation and care. European botanists erroneously asserted that the peculiar newcomers were thistles (Greek: kaktos) and the name, so to speak, stuck. The main attraction of cactus, other than being strange, was that it was distinctly American.

Any cactophile with snap knows that Texas is the epicenter in the United States for these spiny devils. Sure, a lot of people might think that Arizona is the place to see the most cacti, but for sheer numbers no state can top Texas. With 106 species and 142 recognizable forms, Texas has more species of cactus than all the rest of the country. (All told there are probably over 3000 known species.) Not only that, Texas has two of the country’s leading cactologists: Barton H. Warnock of Sul Ross University in Alpine and Del Weniger of Our Lady of the Lake College in San Antonio.

But you don’t have to be an expert to have real cactus pride. West Texans, for instance, have been making cactus jelly for decades from the barrel cactus. This species, which is also the longest-lived Texas cactus (up to 75 years), is the one that has saved the lives of all those thirsty heroes we’ve seen in the movies. If you cut a plug from the top of a barrel cactus, a warm, gelatinous liquid will slowly fill up the hole. While not tasty enough to be bottled, it can be mighty appealing after several days in the desert without food or water.

Texas ranchers have also made great use of our omnipresent friend, the prickly pear. In droughts and hard times, they burn off the thorns, usually with flamethrowers, and feed the tasty young pads and fruit to their cattle. The down side of this practice is that the animals often become semiaddicted to the diet and will secretly eat wild, untreated cactus. If the cattle aren’t kept out of the cactus patch, their mouths become seriously inflamed. What does the damage are the insidious, almost invisible thorns of the prickly pear called glochids.

Despite the risks, cactus is widely eaten not only by bovines but also by humans. Who knows—one of your best friends may be a closet cactophage. All cactus fruits are nonpoisonous and quite edible, as are many of the pads, if you’re not too persnickety about taste. Most people agree that the pitaya, or strawberry cactus, has the tastiest fruit, but a vocal minority of cactus eaters claim that the tuna cactus (a type of prickly pear) is the best all around. The fresh, young prickly pear pads (Spanish: nopalitos) can be scrambled with eggs Mexican style or battered and fried; they taste something like eggplant. The best jelly is definitely made from the tuna, though even the casual cactus cook will strain the jelly to remove renegade glochids. There’s nothing worse than having a throat full of miniature cactus needles with your biscuits.

As long as we’re dealing in scare stories, we might as well get the “horse crippler” out of the way. Surely the most fearsomely named, the horse crippler is a tuber cactus that grows mostly underground. The pad, as big as a dinner plate, contains large, hooked, brittle spines, each about the size of a toothpick. Since the plant is usually hidden by brush, the average, not-so-smart horse often makes the unfortunate error of stepping on it. Hence the dreadful name.

In spite of its infamy, the horse crippler minus its thorns is a surprisingly delicate plant. Like all cacti, it is basically a living column of water. Thick, waxy skin and an armor of spines are the only protection cacti have against parched livestock, humans, and desert pests. And, although not many people would believe it, cacti are also susceptible to sunstroke. What keeps them going under extreme desert conditions are adaptations like little woolly tops that provide a bit of shade and closely overlapping thorns that cast an intricate pattern of shadows.

Considering their unusual appeal and manifold uses, it’s amazing that cacti haven’t become a fad in this country before now. Cactus wood, for example, generally comes from the cholla, or cane cactus. This material, which is riddled with holes like Swiss cheese, has been carved into lamp bases, knife handles, and a host of other accessories. Before the advent of chemical dyes, prickly pear was cultivated to feed vast herds of cochineal insects, the source of a fine red dye that has even been used in lipstick. Not only that, in the Southwest and Mexico, farmers often plant prickly pear as formidable living fences. The spines of the tasajillo, Texas’ meanest cactus, supplied Victrolas with phonograph needles for years, and the thorns of several cacti are used by the loggerhead shrike, a crafty songbird, to impale grasshoppers for handy snacks.

And need we remind you of the use found for the peyote cactus (its name comes from the ancient Nahuatl word peyotl) by resourceful young Americans during the late sixties? Thanks to them, Mother Nature’s own psychedelic can now be legally consumed only by members of the Native American Church. Other than that, this legacy of the Aztecs is largely a thing of the past due to federal legislation and the overgrazing of peyote patches by nature-loving hippies and organic thrill seekers.

Because the peyote is plump and round, it is sometimes known as the dumpling cactus, which brings us to yet another curious aspect of these denizens of the desert: their multitudinous forms. Other plants are perfectly content to look like plants, but not cacti. Given half a chance a cactus will assume any disguise. Some of the decidedly more unusual ones are the living rock cactus, brain cactus, bunny ears, beaver tail, grizzly bear, pipe organ, teddy bear, rattail, hedgehog, peanut, pine cone, eagle claw, and bird’s nest. Our favorite so far is the inimitable discocactus. (It does not, thank goodness, look like John Travolta.)

But whatever their shape—green and lean or flat and flowered—cacti are one of the New World’s great inventions. The next time you see one of our thorny friends, be glad you’re a Texan and quietly ponder whether the Yellow Rose of Texas was really the blossom of the prickly pear—or just should have been.

- More About:

- TM Classics