This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

What struck him, he would later say, was that the boy didn’t look anything like a junkie. Plano Police sergeant Aubrey Paul had driven north along Texas Highway 289, where Plano’s gated communities and mirrored office parks abruptly give way to unruly stretches of buffalo grass, to check out a call he had received the day before from a detective in the neighboring town of Frisco. This was before he knew the full scope of the problem, before his heart would sink when calls like this came in, back when he knew more about heroin from watching The French Connection, he recalled with a half-hearted grin, than he did from his twelve years as a cop. What awaited him in the brick police station in Frisco that day was a jarring revelation: crime scene photographs of a seventeen-year-old who had died of a heroin overdose only a few months after moving there from Plano. Paul studied the photos—an otherwise healthy-looking kid, nude and sprawled across a bathroom floor—and felt a kind of dread. Maybe this was the beginning of something much larger. Maybe there would be more pictures, these gruesome still lifes, to come.

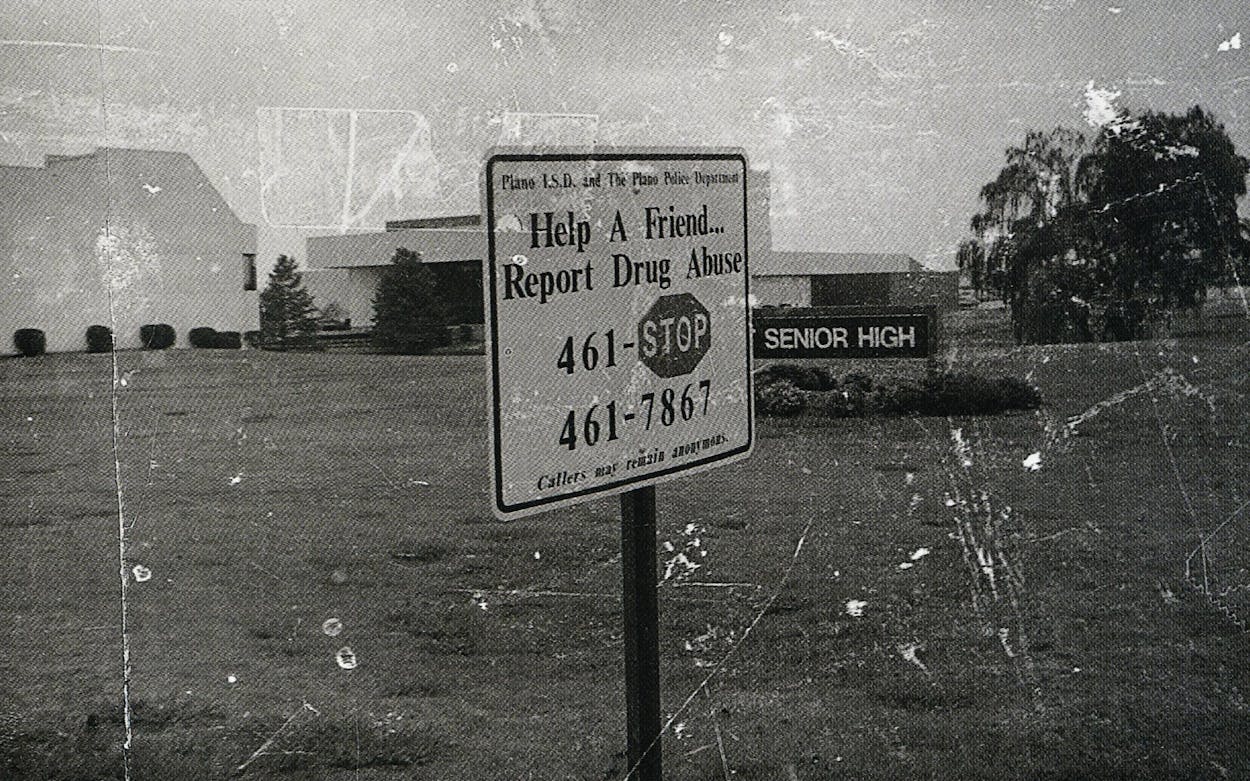

Back then, a little more than two years ago, Paul could not have imagined some of the things he would soon see: the kids shooting up in fast-food parking lots; the girl on the high school swim team who traded sex for heroin; the football player who threw away a college scholarship for his love of the drug, holing up in a $25-a-day hotel room to shoot it. He tells these stories as we drive along the orderly streets of Plano—a city that looks remarkably like anyplace else except that its sidewalks are a little cleaner, its cars newer, its lawns more carefully tended—accentuating what he already knows too well: This wasn’t supposed to happen here. Plano is one of Texas’ most affluent communities (median income: $58,000) and one of the safest cities in the nation (number ten, according to Money magazine’s 1997 rankings). With 206,000 residents, many of them recent transplants, it is also the fifth fastest-growing city in the nation. People don’t flock to Plano for complicated reasons; they do so because it is a boomtown, the sort of place that promises to be better than whatever was left behind. It has optimistically broad streets and oversized cantilevered homes with cathedral ceilings that soar skyward, and it is flanked on both sides by symbols of industry. At the farthest reaches of the east side of town lies Southfork Ranch, where J. R. Ewing once presided over his oil empire; on the west side, where the carefully manicured grounds of Fortune 500 companies line Legacy Drive, stands a bronze statue of department store magnate J. C. Penney, his outstretched hand gesturing toward the half-built subdivisions that dot the landscape.

Plano is the suburban ideal taken to its extreme, and its exaggerated scale often gives rise to exaggerated problems. This is the backdrop on which suburbia’s failings, particularly for teenagers, often first unfold. In the early eighties, when Plano’s population began to climb, there was a rash of teen suicides. Now heroin has hit the city hard: There have been fifteen fatal overdoses in the past two years, nine of them teenagers, all but one younger than 23. They came from good homes and had bright futures: a young Marine home for the holidays, a philosophy major at the University of Texas at Austin, a high school senior preparing for a summer trip to Europe, a football star from Plano East Senior High. The youngest to die was a seventh-grade soccer player whose body was found in a church parking lot. What is astonishing, however, is not how many lives heroin has claimed here but how few, since a staggering number of people—more than one hundred, by one emergency room doctor’s estimation—have been admitted to the city’s hospitals in the past two years while overdosing. And no death toll can convey the other devastations: the twenty-year-old doctor’s son who sits in the Dallas County jail because an elderly woman died of a heart attack while he was robbing her for drug money, or the eighteen-year-old son of a J. C. Penney Company executive who was revived after falling into a coma but suffered such severe brain damage that he can no longer speak or walk.

The residents of Plano are well-meaning and hard-working people with no patience for fatalism or even pessimism about their ability to win this battle. They are problem solvers—corporate executives and mid-level managers who believe that each problem must have its logical solution, that with some elbow grease and determination and a well-thought-out plan, they can rid their community of even this most unimaginable of scourges. “Our purpose here tonight,” a minister told a crowd of 1,800 at a standing-room-only town hall meeting about heroin use in November 1997, “is that our fear might be calmed and wisdom might prevail and that we might claim our city as a shining example of what people working together can do.”

They have waged an impressive fight, mostly in a series of elaborate stings—including a seven-month undercover operation by a 28-year-old police officer who posed as a high school senior—carried out by the narcotics department Sergeant Paul heads up and which coincided with a sweeping federal investigation. This month marks the culmination of their work: On January 5, sixteen defendants will stand trial in federal court on charges that they engaged in a “calculated and cold-blooded” conspiracy to distribute heroin in Plano. Mostly Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals—some with nicknames such as Beefy and Dreamer—they are believed to be the primary heroin distributors in Collin County. (Nearly a dozen others in their teens and early twenties were included in the original federal indictment, for dealing heroin to their friends, but they have plea-bargained and received relatively light sentences.) Prosecutors will attempt to trace the heroin that was found in the bodies of four deceased overdose victims back to them and use an obscure federal law that adds a minimum of twenty years to dealers’ sentences if the drugs they peddled resulted in a fatal overdose. These are effectively murder charges; if convicted, the defendants could be sentenced to life in prison.

This is reassuring news to many people in Plano, as is the substantial new federal funding for drug-fighting efforts in the area. U.S. drug czar Barry McCaffrey designated Dallas a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area in October, earmarking $5 million for the Metroplex, and the Senate has set aside $28 million to fund anti-drug task forces already under way around the state. The Betty Ford Clinic has even established its first satellite program in Irving. In light of these developments and the upcoming federal trial, there is a sense here that this war has largely been won. A recent town hall meeting about heroin use drew scarcely fifty people. In a poll last fall residents said the city’s two most pressing problems were overcrowding and materialism.

Few people are talking about the fact that many teenagers here are still using heroin and that the problem is quietly spreading to other suburbs around the Metroplex: Garland, Richardson, Carrollton, Grapevine, Hurst-Euless-Bedford, Arlington, North Richland Hills, Haltom City, and as far north as Denton. “When you used to page a dealer, he would meet you in ten minutes,” one nineteen-year-old told me. “Now there’s so much demand that you have to wait.” Overdose statistics are difficult to come by since medical examiners are not required to identify overdoses by the specific drug that caused them, but it is clear that every major Dallas suburb has had at least one fatal heroin overdose this year. The statistics that are available are startling: The number of people in the Metroplex seeking treatment for heroin addiction rose 300 percent in the past two years. Drug seizures in North Texas rose by 400 percent last year. Plano’s most recent overdose death, that of eighteen-year-old Tyler Marston, occurred during the same week in November as the overdose deaths of a sixteen-year-old in Lake Dallas and a nineteen-year-old in Arlington. The previous month there had been five fatal heroin overdoses in Tarrant County alone.

For Sergeant Paul, whose team of undercover officers has worked hard to keep the threat of heroin at bay, such numbers are dispiriting. As he drove me through the streets of Plano to the house that serves as home base for the city’s undercover cops, I thought of news footage I had recently seen: shots of uniformed federales brandishing sticks in the poppy fields of southern Mexico, swatting at the crimson-colored flowers until their petals fell to the ground, and I wondered if he too was fighting a losing battle.

Plano was named for the plains, the rich blackland prairie of cotton farms and alfalfa fields that once rolled out beneath the sky toward Oklahoma. In 1960, when it was still a quiet, mostly Baptist farming town, it had only 3,500 residents, and the bulk of its land was owned by the Haggards and the Harringtons, two local families who had been there since the 1850’s. Plano was dry then, and there wasn’t much to do on a Saturday night other than tool down a country road with the radio on or maybe head over to Lake Dallas for a six-pack. Even as recently as the late sixties, it had little more than a Dairy Queen and a pharmacy for landmarks. But in the sixties and seventies, expansion of Central Expressway turned the two-lane ribbon of blacktop that ran through Plano into one of Dallas’ major urban arteries, quickly transforming the town into a bedroom community. By 1981, with the construction of the Collin Creek Mall, then the largest mall in North Texas, and the relocation of several Dallas businesses, it had become a full-fledged city. Within a few years most of the prairie land had vanished, swallowed up by rows of strip malls, office parks, and cul-de-sacs. In the tony Willow Bend neighborhood, the towheaded prairie grasses have been tamed into polo grounds.

Although Plano begins east of Central Expressway—where modest frame houses lie near its former business hub, an unhurried street of antiques shops that dead-ends at the rusting railroad depot—the city has grown rapidly westward. These days, the heart of Plano lies on the other side of the expressway, where six-lane boulevards slice the city into a grid of disorientingly similar streets. Locally owned businesses are rare in this land of high-end franchises and upscale chain stores; even the French restaurant is part of a national conglomerate. A ready-made community for newcomers, West Plano seems designed to feel immediately familiar with its man-made ponds, newly planted saplings, and sod that is kept a vibrant green under the spray of a thousand sprinkler systems. This is where the city’s subdivisions and gated communities lie, their streets lined with ordinary split-level homes as well as what residents jokingly call “tract mansions”: enormous redbrick houses that can be differentiated from one another only by tiny regal flourishes—an ornate brass knocker, a stained-glass window above the entryway—that look like developers’ afterthoughts. Many of these neighborhoods are only partially built, bearing signs (“Homes Beginning at $400,000″) that attract buyers while buzz saws hum in the background.

Plano no longer has a downtown. Legacy Drive, where the city’s ambitions are proudly displayed, is the closest thing to a town center. Ross Perot bought a large spread of land in West Plano’s northwest corner in 1982 and built the monolithic, reflective green-glass bunker, surrounded by a chain-link fence and barbed wire, that now serves as headquarters for Electronic Data Systems. EDS, like other corporate headquarters along Legacy Drive, is a small civilization unto itself, with its own auto repair center, a 60,000-square-foot health club, even a sunken lake and waterfall to contemplate while eating at one of its three cafeterias. It is a place of surprising uniformity—until this past fall, male EDS employees were required to wear ties and white dress shirts—and its design reflects a rigid hierarchy; its elevated executive suites, which soar over the two-story-high palm trees of its central atrium, are referred to by employees as the God Pod. Each EDS entrance has its own armed guards, surveillance cameras, and tire shredders to help fend off terrorists and corporate spies. Farther down Legacy Drive are the headquarters of Frito-Lay, Dr Pepper/Seven Up, Fina Oil, and a host of other companies, each one a sleek monument to corporate efficiency. The low-slung headquarters of J. C. Penney—which has its own jogging trails, day-care center, and robots that sort the mail—would be a one-hundred-story tall skyscraper if turned on its end.

This is a community of strivers—of people who came here to further their careers or improve their standard of living—and the burden of their expectations often falls squarely on the shoulders of their children, who are meant, without exception, to excel. Averageness is not looked kindly upon. There are cheerleading classes for toddlers, SAT prep classes for students who have barely begun high school, and a dizzying array of extracurricular activities that promise to give kids an edge over the competition. Plano Senior High reminds students of what is at stake with a map that hangs near the cafeteria; it tracks where seniors are heading to college with brightly colored thumbtacks, the plastic nubs clustered around the country’s finest universities. Plano’s senior high schools are among the most rigorous in the state and consistently triumph in any sort of achievement that can be ranked, scored, or tallied. They have some of the highest SAT scores in Texas and the second-largest advanced-placement program in the country, and they have won dozens of state athletic championships. A preoccupation with being number one is the unofficial reason that Plano Senior High and Plano East Senior High, both of which educate only eleventh and twelfth graders, have had unusually high enrollments, with 3,336 and 2,336 students respectively, giving coaches large pools of potential players from which to pick winning football teams. This fall a third senior high will open.

In general, teenagers in Plano are less anxious about fitting in than they are about succeeding. The pressure they feel to live up to their parents’ expectations takes an extraordinary toll; high school students speak not only of insomnia and eating disorders but also of stress-related hair loss and ulcers. Disappointment over grades was commonly blamed for the spate of suicides that began in 1983, a phenomenon that first illuminated for parents a level of teenage despair that seemed at odds with the community’s middle-class comforts. What local teens nicknamed the Death Club began inauspiciously enough on February 23, 1983, when a sixteen-year-old whose best friend had just been killed in a car accident was found in his car dead from carbon monoxide poisoning as Pink Floyd’s “Goodbye Cruel World” played on the tape deck. Six days later, an eighteen-year-old killed himself, also by carbon monoxide poisoning, and that spring a fourteen-year-old shot himself with a .22-caliber rifle; both suicides, it was speculated, were the result of the pressure to get good grades. In August came the suicides of seventeen-year-old sweethearts who couldn’t bear to stop dating as their parents had ordered. Later that week, an eighteen-year-old died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds, distraught over breaking up with his girlfriend, and the following February a fourteen-year-old shot himself with a .357 magnum after having his teeth fitted with braces. More than a dozen other Plano teens tried to kill themselves. Some ransacked their parents’ medicine cabinets for pills (Valium, Tylenol, Anacin, Sominex, even Alka-Seltzer) that they then took in great number. Others slashed themselves with razors, and one teen used a pair of scissors. One boy tried to hang himself with his shirt.

Then, as now, national headlines resounded with the same question, Why Plano? Some blamed the city’s rootlessness, others its high expectations; the Centers for Disease Control investigated and found no particular cause. With the exception of the high school sweethearts, none of the teens wrote suicide notes, leaving parents with the unhappy task of examining why their kids, who had been given everything, chose to throw it all away.

Parents would grapple with the same question more than a decade later when heroin first made its presence known, and they would find themselves similarly unprepared. Belita Nelson, formerly the debate coach at Plano East Senior High, told me about the day she found needles and a syringe in her house. “My first reaction was, ‘Who do they belong to?’ ” she recalled, “because I knew they weren’t Jason’s. He had just finished a summer program at Dartmouth, he was making A’s and winning debate tournaments, he never came home late, he was dating the right girl. This was the kid at the doctor’s office who would scream bloody murder when the doctor got out the needle. We think we know our children so well.”

The heroin came from the foothills of the Sierra Madres—scarlet blossoms that when cooked down to a gummy paste over makeshift grills in the poppy fields of Southern Mexico promised to deliver everything that Plano was not. “When it hits you, you feel no pain, no worries,” says seventeen-year-old Jonathan Kollman, a minister’s son who is serving a one-year sentence at the Collin County jail for dealing heroin. “You feel really relaxed and good inside.”

First synthesized for wounded soldiers, heroin’s express purpose is to inhibit the brain’s ability to perceive pain; it also mimics the body’s natural production of endorphins, but at an accelerated rate. The initial rush is a rapturous, slack-jawed jolt that lasts for a minute or two, after which the drug’s euphoric effects fade into a warm, drowsy state that lasts for several hours. Unlike cocaine or speed, heroin slows things down to a pleasurable state of apathy, giving the illusion that all needs—hunger, thirst, human interaction—have been fulfilled. “It takes the edge off things,” Clay Roper, a soft-spoken twenty-year-old, told me as he sat at his mother’s kitchen table, his hands folded neatly in front of him.

Mexican black tar heroin, known by the nickname chiva, came to Plano by way of Laredo, where it was hidden in the hollowed-out soles of shoes and walked across the border, then driven up Interstate 35 to Dallas and destinations beyond. Competition between the Mexican and Colombian drug cartels for control of the emerging heroin market drove up the purity of the drug—from 5 or 6 percent a decade ago to upward of 50 percent in the past two years—making it a popular drug with a new crowd: Its potency meant that it could be snorted rather than injected, delivering the same high without the needles. “No one would have touched the stuff if it meant sticking a needle in your arm,” explains nineteen-year-old Sean Isaac, an affable blond who attended the same rehab program as his father, a recovering cocaine addict. Neatly packaged in gel caps, it was the blissful high of heroin without the mess, and many teenagers figured that if they weren’t shooting it, they weren’t in danger of developing a habit. It was cut with Dormin, an over-the-counter sleeping pill that slowed down the high, prolonging its effects and eliminating heroin’s runny noses and watery eyes with an added antihistamine, and it was given away for free at first, handed out along with the pot and cocaine that teenagers were already buying on the east side. Dealers started charging for it once they had repeat customers, offering free caps to those who brought friends back with them.

Heroin easily slid into Plano’s weekend scene, in which teenagers often drove out to field parties on the fringes of the neighboring towns of Allen or McKinney, where they could set up a keg or pass around a joint without looking over their shoulders for cops. There was no great mystery as to why they started experimenting with chiva: It was regularly described as the best high anyone had ever felt, and it was perfect escapism. “It was always, ‘Let’s get messed up this weekend,’ ” says twenty-year-old Chris Cooper, a clean-cut Plano Senior High dropout, describing the boredom, drinking, and casual drug use that is by no means unique to Plano. “You want to party with your friends and feel good, to get that buzz. You don’t think about the future.” The son of a Dallas television producer and a resident of a well-heeled West Plano neighborhood, Cooper had already experimented with a number of drugs, beginning with pot in the eighth grade. In his senior year he was curious enough about chiva that he tried it for the first time one night after dinner while his mother was washing the dishes. He reached for a cap that friends had given him—he had tucked it under some shirts in his bureau for safekeeping—and snorted it, as he had done before with cocaine, lying down on his bed to wait for its effects. “It was this tranquil feeling, this amazing numbness,” he remembers. The next day he asked around about getting some more, and it wasn’t hard to find; one dealer sold chiva in the parking lot of the Disciples Christian Church across the street from Plano Senior High, while others would meet customers at the nearest gas station whenever they were paged. For the under-21 crowd, it was easier to get than beer: No one asked to see your I.D.

Heroin was seemingly without boundaries, a drug that people in all cliques—“The cheerleaders and the football players and the computer geeks and the guys with 3.5 GPAs,” says one recovering user—were experimenting with. Some had used pot, acid, or cocaine before, but heroin had its own particular appeal, and for people who got hooked, weekends quickly degenerated into finding a place “that we wouldn’t have to move from,” Cooper says, “where we could sit around and nod off.” For some teenagers, doing chiva every other weekend became doing chiva every weekend and then every day; initial withdrawal symptoms—achy joints, muscle spasms, hot-and-cold flashes—kicked in on days when they didn’t use it. “I started waking up in a cold sweat, and pretty soon I needed caps just to function,” Cooper recalls. “I would do a couple in the morning to feel normal, the way other people have a cup of coffee.”

Caps generally cost $10 apiece; addicts would eventually need roughly $100 a day just to prevent themselves from going into withdrawal. The crimes they committed to finance their habits were almost comical for their innocence: Scavenging suburbia, they stole golf clubs out of neighbors’ garages, pawned their parents’ power tools, shoplifted CDs from Wal-Mart and video games from Blockbuster, lifted $20 bills out of their mothers’ purses. One boy told me sheepishly that he had pawned his father’s Mickey Mantle baseball card.

Some teenagers began selling it to their friends to pay for their own habits, buying black tar heroin from dealers before it was cut, mixing it in hand-held coffee grinders with Dormin, and eyeballing the color and texture to gauge its potency. It was an inexact science, often producing chiva that was alarmingly strong. Recovering addicts spoke of vomiting repeatedly after using it and even being thrown into cold showers and slapped awake by friends as they slipped into unconsciousness. Sometimes they were too late, as Dr. Larry Alexander remembers from his tenure at the Medical Center of Plano emergency room in 1997 and early 1998, when weekends often brought in panicked teenagers whose friends would not wake up. He recounts the not uncommon story of one boy who later died: “His friends started beating on the doors, yelling and screaming, ‘He’s not breathing. He’s not breathing!’ He was blue, and he was lying in the back of a Suburban. We put him on a gurney and started running him back into the ER. The next thing I heard was tires peeling out. His friends had taken off, and we had no idea who he was.” Other times, Alexander says, teens would call 911 when a friend had overdosed but bolt from the scene for fear of being arrested, leaving a door open for medics so that they could reach the victim.

The naiveté of some teenagers about the power of the drug they were using would cost a few of them their life. Friends of one boy, who had vomited on himself after shooting up, tried to wash him off by putting him in a Jacuzzi, where they left him, in a daze, to drown. Others waited too long to call an ambulance—a mistake that would end in the fatal overdose of one of Cooper’s friends, Milan Malina, whom he had first met in ninth-grade gym class. On Malina’s twentieth birthday, nearly a year and a half ago, friends gathered at a house in Willow Bend and passed around champagne, pot, and chiva; Cooper had provided the heroin. Malina had been clean for nearly two months, so he had a far lower tolerance for heroin than usual that night. He snorted two caps of chiva, and by the end of the evening, his speech was slurred and he was having difficulty walking. His friends told him to sleep it off, and so he lay semiconscious in a bedroom for several hours, feverish and vomiting. Cooper had already returned home by the time someone discovered that Malina wasn’t breathing anymore. He met them at the emergency room, where a doctor directed him and seven friends into the room where Malina’s lifeless body lay, his face blue and caked with blood. “The doctor wanted us to see what had happened, to really look at him,” Cooper says, his eyes fixed on the ground. “It was awful.”

Except in life-threatening cases or death, hospitals are not required to notify parents of emergency room admittances if their child is sixteen or older, so often parents had no idea what sort of trouble their children were getting into. There were few obvious signs to look for, since many addicts—unless they had graduated to needles for a stronger high and had been shooting up for a substantial amount of time—often maintained their grades and a healthy, clean-cut appearance. And many parents refused to believe that their kids were using drugs in the first place. “For parents, the denial is incredible,” Alexander says. “I had one man push me to the wall after I’d saved his son’s life and tell me that I’d faked the drug test, that it couldn’t be heroin. He told me it would ruin his son’s chances of getting into college.”

Sergeant Aubrey Paul is well liked by his undercover officers, a boisterous, tight-knit bunch whose long hours working together have forged an intense camaraderie. With short brown hair, a clean shave, and the rigid posture of a onetime military man, 35-year-old Paul is more buttoned-down than the other undercover narcs, although he can easily transform himself from cop to civilian with a quick shift in body language. Slouching in the seat of his pickup with an easy smile, drawing out the cadence of his native Louisiana, he is equally convincing as a good ol’ boy looking for the next high.

In the summer of 1997 Paul taught what he knew about undercover work to Margaret Owens (not her real name), a then-28-year-old police academy recruit he hoped could lead them to the teenagers dealing heroin in Plano’s high schools. “That subculture is very difficult to penetrate,” Paul explains. “When we sent an undercover officer into the schools in 1986, he could hang out in the smoking lounge with the kids in the Molly Hatchet T-shirts and say, ‘Hey, do you know where I can get some weed?’ But now everyone looks the same, and its harder to tell who’s using and who’s not. It has gone further underground. You can’t go up to a group of football players and say, ‘Hey, where can I get some heroin?’ ”

Owens seemed like the perfect candidate: a willowy blond who had grown up in the suburbs of North Dallas, she looked the part, her body still slight enough to be a teenage girl’s, her face youthful and freckled across the bridge of her nose. Paul and the other undercover officers taught her the tricks of the trade and then enrolled her at Plano Senior High using doctored copies of her original high school transcripts. They bought her the props she would need: a cell phone, a red convertible, and an apartment a few blocks away from school. She was also given a new name, a different driver’s license and social security number, and a cover story: Her parents in Southern California had become exasperated with her wild behavior and had sent her to Plano to live with her uncle (played, when necessary, by Paul) until she straightened herself out.

“I would sit in the mall for hours studying the other girls, watching what they wore and how they talked and what music they listened to,” Owens recalls. “I had to forget everything they’d taught me at the police academy, where they drilled it into us to stand ramrod straight and speak with authority, and remember what it felt like to be seventeen and unsure of yourself again.” She streaked her hair with highlights, put extra foundation on her face so that her skin would break out, and painted her nails with intricate designs that she hoped would spark conversations with other girls. For the first day of school, she carefully picked out an outfit: baggy hip huggers that flared slightly at the bottom, silver thumb rings, and a snug, short-sleeved shirt. “I thought I could feel their eyes burning into the back of my head, thinking, ‘She’s too old. She’s too old,’ ” Owens says. “I was sure the lines around my eyes were going to give me away.” During classes, she affected a disinterested gaze, alternately drawing in her notebook and staring out the window, listening in on conversations where she could. Cigarettes weren’t allowed on school grounds, but she kept a pack of Marlboros in her purse and left her bag open alongside her desk so that they were within easy view. It was a good trick: Girls approached her after class and asked if they could bum a cigarette, and by the end of the day, she was beginning to collect names. “They bought it,” she wrote in her journal that night. “I’m a teenager.”

New students were the norm rather than the exception in Plano’s sprawling senior high schools, and she easily became friends with students who had access to a wide array of drugs. She began buying pot and then chiva from them after school; friends were kept at arm’s length so that they wouldn’t ask too many prying questions, and she avoided parties where it might be considered odd that she wasn’t using the chiva that she was so often in search of. Friends sometimes took her along to buy from bigger dealers, and when they dashed out of the car to trade money for caps, she quickly wrote down dealers’ license plate numbers and addresses on the soles of her shoes. “She played it off real well,” explains Jonathan Kollman, who unknowingly led Owens to other dealers and was prosecuted with evidence that she had gathered. “One time someone sold us empty caps, and she got real mad, just like a junkie would.”

Owens transferred to two other schools during the course of the academic year, gaining the trust of students with a few simple overtures: mouthing off to teachers, wearing revealing clothes that pushed the rules, even getting her tongue pierced in Deep Ellum with some acquaintances. Her act went over well with everyone except for one boy, the older brother of a girl she bought drugs from. When the girl told Owens on the phone that her brother thought she was a narc, she laughed it off easily enough, but privately it sent a chill through her.

The arrests came on a drizzly gray Monday morning in March, when dozens of squad cars pulled up to Plano’s high schools after the bell rang for first period. Students were pulled out of class and handcuffed in the principal’s office, and they looked bewildered as they were led outside. All told, 38 people were hauled off, 19 of them students—a major victory for Paul and his officers, who had nabbed key members of the Pineda family, the city’s top heroin dealers, the previous week with the help of state and federal law enforcement agencies.

As news of the undercover operation in Plano’s high schools broke on several Dallas TV stations, the undercover officers were elated, and Paul planned to take Owens and his crew out for a steak dinner to celebrate. Early that afternoon, however, he got a tip that a car heading south toward Dallas would be coming through Plano along Central Expressway carrying several pounds of methamphetamines: the drug that law enforcement officials fear will soon rival heroin in North Dallas. Paul knew his department had a job to do, and in the end, there was no celebration that night, only fast food and the droning sound of traffic, as his officers hunkered down in unmarked cars by the side of the expressway, waiting to fight this next battle.

On a brisk Tuesday evening this October, Paul and I drove down Central Expressway to Dallas, where he promised to show me a spot where Plano teens were now coming to buy heroin. Heroin is currently much harder to come by in Plano after the police stings, teenagers had told me, but in Dallas, black tar was easier to find than pot, and even China White—a stronger, more refined heroin from Asia—was becoming readily available. Paul is keenly aware that even his department’s monumental successes are short-lived, but he remains fiercely committed to his task. “If we hadn’t aggressively pursued these dealers,” he observes, “many more kids would have died.”

Rounding the corner of a gas station in a well-to-do neighborhood, we spotted three teenagers in a white Volkswagen, its engine running, parked toward the rear of the lot. Paul read its license plate numbers over the police radio to a dispatcher back at headquarters, who confirmed that the car was registered to a Plano address. A few moments later, after a dealer drove by, the Volkswagen lurched out of the gas station and began the strange cat-and-mouse game that many users had previously described to me. Weaving down side streets, the Volkswagen followed the dealer until he abruptly turned his car into an alleyway and stopped, leaving the motor running. The Volkswagen driver leapt out of the car, handed over cash, and shoved what was handed to him into his pocket; then they both sped off into the night. We briefly tailed the dealer until he lost us in a maze of side streets. “They’re here every night,” Paul said after we had lost sight of him. “We’ll catch up with him sooner or later.”

- More About:

- Mexico

- Ross Perot

- Plano