This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Fade in

A field of bluebonnets in the Texas countryside. A young boy is seen running through the bluebonnets, followed by his mother, who is also running.

Woman (voice-over, singing)

Softly and tenderly Jesus is calling,

Calling for you and for me;

See, on the portals he’s waiting and watching,

Watching for you and for me.

Come home, come home,

Ye who are weary, come home;

Earnestly, tenderly, Jesus is calling,

Calling, O sinner, come home.

Thus begins the screenplay for The Trip to Bountiful, the 1985 film that earned Horton Foote his third Academy Award nomination for screenwriting. He didn’t win that year, but Bountiful might well be a better script than the two for which he did win, To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and Tender Mercies (1983). Academy voters probably figured that he had been recognized sufficiently by then.

Geraldine Page, an old friend who had previously been nominated seven times without winning, finally won the best actress Oscar for her portrayal of Carrie Watts in The Trip to Bountiful. “It’s all your fault, Horton,” is what Page had to say in accepting her award. She hadn’t even read the script when she took the part. “When I knew Horton had done it,” she said, “I accepted immediately. He writes real characters using real dialogue.”

For three generations now, many of America’s finest actors have been accepting parts without reading the scripts, simply because Horton Foote wrote them. From Gregory Peck to Robert Duvall to Matthew Broderick, they have been inspired to do their best work by playing roles that he created, speaking words that he put in their mouths. Peck and Duvall each won best actor Oscars for their readings of his lines, and Broderick has won acclaim on Broadway for his performances in Foote’s plays, just as his father, James, did.

They are never flamboyant, glamorous parts concocted with an eye on the box office and a deaf ear to real human speech, as so many film and stage roles seem to be. No Horton Foote character is larger than life or confronts a dilemma that we can’t identify with. They are no more clever or muscular or beautiful or villainous than the rest of us. Like us, they are only trying to cope with the indignities of the human experience, weary sinners yearning for a call to come home.

The world that Horton Foote has created is set around the imaginary Gulf Coast town of Harrison, Texas, which used to lie on a rail line with Bountiful and Cotton, somewhere west of Houston, just about where the real-life town of Wharton is found. It is rich, flat bottomland country, perfect for planting cotton or sugarcane, which is what drew Albert Clinton Horton to Wharton County in 1834. A very tall—six feet seven—very handsome gentleman-planter, Horton settled on five thousand acres in the area, and he brought with him 120 slaves.

Horton would go on to become lieutenant governor of Texas, remaining a Southerner until his death at the end of the Civil War. “I presume of a shattered, broken heart,” says his great-great-grandson Horton Foote. “I think he just lost everything.”

In the mid-twenties the young Horton Foote was making a fourteen-mile hike to qualify for a Boy Scout merit badge when he came upon an isolated country store, where an old black man sat on the gallery. Being a talkative boy, he struck up a conversation with the man, who asked his name. When told, the old man replied quietly that he had once belonged to the boy’s great-great-grandfather.

“It was a powerful moment for me,” says Foote today. “I had heard stories about how our family had owned slaves, but it was always an abstraction. This man, this tired, suffering human being, suddenly made it very real, very personal. I never listened to those old stories again without seeing his face.”

It was the kind of moment that could be the turning point in a Horton Foote play, which is usually a drama of subtle awareness. His central characters are almost always the young and the old, and the interplay between them gives meaning to the act of living. That has certainly been true of his own long life.

“I had a very happy, wonderful childhood,” he says, looking out from the breezy front porch of the house in Wharton that he grew up in. He points to a pair of soaring, eighty-foot pecan trees that were planted in 1916, when the house was being built. “I used to climb all day long in those pecan trees. My father planted them the day I was born.”

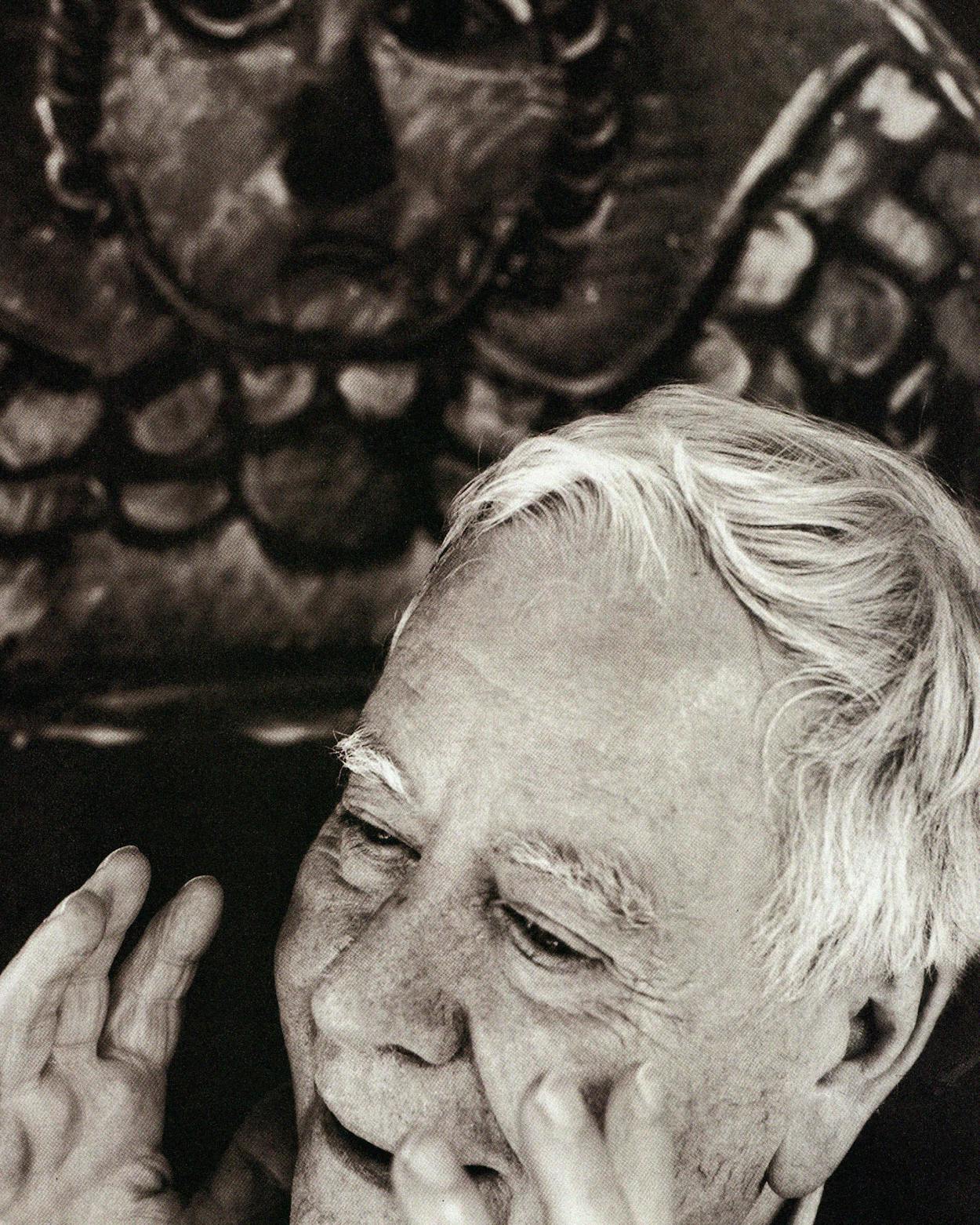

His voice is soft, sweet, and seductive, a finely tuned theatrical voice. It took years of lessons in his younger days to refine his Texas drawl, which lingers today only as the slow cadence of his carefully chosen, accentless words. His hair has turned ghost white, and his features have filled out with age, giving him the solid look of that classic Texas character, the city man retired to the country and better off for it. He still wears his city uniform every day—white shirt, rep tie, blue blazer—but he seems quite at home as he sits back in the rattan chair on the wide porch.

“I used to lie in there in bed,” he continues, pointing to a window on the corner of the porch, “and listen to my parents and grandparents talk out here. In those days that’s what people did at night, sit on the porch and talk. I used to love to listen to them.”

In the crucial scene of To Kill a Mockingbird, the young girl Scout listens through just such a window as her father, played by Gregory Peck, talks to the county sheriff on just such a porch. The scene was not in the original novel by Harper Lee; it came from the boyhood memories of Horton Foote.

He was a sheltered, privileged boy, the grandson of the richest man in town—his mother’s father. He appears rather effete in childhood photographs. Young Horton had no interest in hunting or fishing or even baseball. His passion was conversation with the many relatives who populated the porches of Wharton, and the hunger that drove his ambition grew not in his belly but inside his head.

As a child, Foote had seen only traveling tent shows and a few silent pictures. Then, on one of the walks he regularly took with his mother and father, they passed a distinguished old gentleman who, his parents said, had gotten a call to become a preacher. “And that word ‘call’ really struck me,” Foote says. “I remember asking if only Baptists got calls. And then when I was ten or eleven, I got a call to be an actor. I really did. In truth, I suppose I just wanted to be a film star.”

In 1930 he won first place in the annual Texas high school drama competition, playing a dope fiend. “The judges asked my teacher if I was afflicted or if that was acting.” It was his parents, most importantly, who discerned the difference. He learned many years later that his father, Horton Senior—who had no benefit of family wealth—sold the only piece of property he owned to send his son to California to develop his dream. The Pasadena Playhouse, where Horton enrolled as an acting student for two years, was then considered a sure stepping stone to a career in nearby Hollywood. The boy’s ambitions, however, soon deviated from the obvious path. His wealthy Grandmother Brooks, by then a widow, came to visit Foote on his birthday and asked him what he would like. He told her that he would like to see some Ibsen plays.

The Norwegian playwright had been dead for thirty years by then, but the new kind of theater that he had created was still moving across the world’s stages, changing them slowly but drastically. An Ibsen play was like an open window onto somebody’s porch, allowing an audience to witness the ordinary dramas of people in distress. It was the beginning of modern theatrical realism, and Horton Foote heard it call to him. “I was so enthralled. That banished any thought of the movies from my mind, I remember that very clearly. I thought that theater was where I really wanted to be.”

Barely twenty, he set off for New York and promptly enlisted in the avant-garde. That meant the Russians, the émigré apostles of Konstantin Stanislavsky who were reinventing the art of acting. In contrast to Broadway’s inflated gestures and pseudo-British enunciation, the Stanislavsky school taught that believable acting came from the actor’s own deepest feelings. As such, it was ideally suited to film, which brought actors so close to their audience. Two decades later, it became famous as the Method, epitomized by the mumbled intensity of American film stars Marlon Brando and James Dean.

In New York in the thirties, though—before it was adapted to Hollywood’s ends—the Method provided an entire ideology of theater. Students were encouraged to mine their memories and evoke the characters they found there, improvising dialogues between them. As exercises, they wrote scenes and monologues based on real situations, dramatizing but not fabricating. The goal wasn’t entertainment but realism. And that is how Horton Foote became a writer.

He was not alone. Thornton Wilder, Clifford Odets, William Saroyan, and Tennessee Williams, a whole generation of young playwrights were putting their pens to work in the American vernacular, setting their plays in everyday America, instead of on Park Avenue, which is where most Broadway plays were set at the time.

The American Actors Theater, which Horton Foote helped found in 1938, was the first place many of them saw their works performed. It was a small rented studio—“Almost a garage,” Foote says—that housed a regular wonderland of theater artists: dancers, actors, musicians, designers, choreographers, writers, and poets. “There were no stars, everybody did everything. It was quite exciting,” Foote says today in his understated way. That is where his first one-act play, Wharton Dance, debuted.

“I suppose I really became a writer in order to give myself all the lead parts,” he says with a chuckle. “It’s odd sometimes how things work out, isn’t it?”

Both the play and its star were well-received, which emboldened him to attempt a full-length play in three acts. In summer 1939, he went home to Wharton to write it. “I wrote it right in there,” he says, pointing through the screen door to the front room of the house. “The writing came very natural and easy for me. I enjoyed it very much. At that time, of course, I was still an ambitious young actor. I felt if I wasn’t a big Broadway star by the time I was twenty-eight, well, life wasn’t going to be worth living. So I was writing myself a good part.”

The play was called Texas Town, and it was presented in 1940 at the American Actors Theater, which had expanded slightly since the garage-stage days. It was a simple drama set mostly in a small-town general store and involving half a dozen townspeople. Brooks Atkinson, the drama critic for the New York Times and the foremost critic of his generation, was captivated. “It is impossible not to believe absolutely in the reality of his characters,” he wrote in a long review. “These are truths of small-town life that Mr. Foote has not invented.”

Atkinson was less impressed, however, with the author’s acting abilities. It was a hard lesson, and it didn’t sink in immediately, but the truth was that Foote’s art lay in his writing, not his performance. Texas Town marked the last time he would star in one of his works. In retrospect, it was the Act I curtain in the artful life of Horton Foote.

Few careers in American letters are as varied and prolific as Foote’s has been. Certainly no other Texas writer has pursued his craft so broadly, so productively, or for so long. Yet his story isn’t one of riches and glory; rather, like the stories he has created, it’s the tale of a survivor, not a hero.

His first foray onto Broadway, in fact, was underscored by disappointment and frustration, establishing a pattern that dogs him still. Only the Heart was well received when it previewed in Provincetown tryouts in 1942, drawing the attention of a Broadway mogul, who booked it the following season. It should have been a triumph for the youthful playwright, not yet 28. The mogul, however, came burdened with “ideas,” dozens of little changes that he felt sure would “improve” the play and, by the way, make it more profitable.

“He talked about how it could make lots of money,” remembers the author, “and our little theater company, you know, we certainly could have used it.” Horton Foote is a courtly man with impeccable old Southern manners, and it’s difficult for him to speak meanly of another person. Still, his distaste for Broadway moguls, even after half a century, is obvious. “He added a lot of technique, I suppose, but basically what all of the changes did was to make the play more conventional. Whatever raw power it originally had was diluted.” He looks away wistfully. “I think it’s fair to say that the rewrites hadn’t helped the play.”

They ruined it is what they did, and the play closed in two months. Flat broke but wiser, Foote went to work in a bookstore “because I’d read somewhere that Faulkner had done that.” A young Radcliffe student named Lillian Vallish was working as a clerk at the store during her summer vacation, and she won his heart completely and forever. Because her parents were none too thrilled by his bohemian prospects, Lillian and Horton eloped in 1945, immediately after her graduation.

On the porch of the home they share in Wharton—the same home his parents shared for sixty years—Lillian Foote is a constant, genteel presence. She may have been born in Pennsylvania, but she runs a house with the graceful will of any Southern matron. During a long afternoon, she answers the phones and opens the mail, double-checks revisions of her husband’s newest play with him, organizes their hectic schedule, and freshens their guest’s iced tea.

One of Horton Foote’s main strengths as a writer is his female characters, who seem always to possess a clear sense of themselves. They are based most often on women he knew in his youth—particularly his mother and grandmother—but surely he must write them with his wife in mind. He would not be a writer today if not for her.

When they got married, he had only recently decided that being a writer was his true calling. “I just shifted gears,” he says. “I decided that if I was going to be a writer, well, I wanted to be the best to come down the pike. By this time, I was known as a promising playwright, which is the most awful thing to be. People would watch everything I did; there were so many expectations. I wasn’t being given the chance to fail.”

They moved out of the limelight for the next few years to Washington, D.C., where he could fail with abandon. He taught at an experimental school, directed experimental plays, collaborated with dancers and poets, and generally limbered his talents. By 1949, he was ready for New York again.

For the next fifteen years he worked in every form that depends on words and imagination to exist, from stage to screen to novels to television, often retooling works from one form into another. Foote achieved his first wide renown during the inspired early years of television, in what is now regarded with misty affection as the medium’s golden age. It was a period of bizarre experimentation, as people sought to learn what the new medium was actually good for. They proved that television’s particular strengths were intimacy and immediacy—up close and personal, live—a combination that has never been blended better than in NBC’s Television Playhouse and CBS’s Playhouse 90. These anthology series of the fifties carried provocative dramas into America’s living rooms like some kind of national porch window, and were tailor-made for the new breed of realists. It was only natural that actors like James Dean and Paul Newman, actresses like Joanne Woodward and Jean Stapleton, directors like Arthur Penn and Vincent Donehue, and writers like Paddy Chayefsky and Horton Foote should all launch proud careers from these low-budget programs.

Foote wrote more than a dozen teleplays in those first years of network television, most of them set in the small town he called Harrison, Texas. Millions of viewers watched his ordinary citizens struggle to keep their dreams afloat in a rising tide of changing times. They were intimate dramas that rarely involved more than a few characters and usually unfolded in kitchens or parlors or, of course, on porches.

It’s hard to believe in our age of facile, predictable television, but those modest one-hour teleplays packed the punch—the good ones, that is—to carry them to Broadway. They were enormously popular, enough to motivate the moguls to expand them and install them in theaters. That’s what happened with The Trip to Bountiful, which was broadcast on Television Playhouse in March 1953 and later moved to Broadway, with Lillian Gish reprising her TV role as Carrie Watts.

During these same years, Foote wrote another dozen plays specifically for the stage, most of them in the same small-town vein but with stronger, broader themes. Some were respectable hits, like The Traveling Lady, which made a star out of Kim Stanley. It is Foote’s best original stage play. Another hit was The Chase, the closest that Foote has ever come to writing an action thriller, which he later reworked into a successful novel that was sold to the movies.

He resisted the call of Hollywood for a long time. Cornell Wilde had lured him to California in 1954 to adapt the novel Storm Fear—a Southern potboiler that made a nice film noir—but Foote wasn’t comfortable. “I really felt like I was slumming,” he says. “I felt that theater was my life and my home and that’s really where I should be. But by that time, we had two children, and you know, I just couldn’t turn it down. I came back to New York as soon as shooting was finished.”

He turned down every offer after that for several years, not even bothering to read the propositions his agent passed along. Then, one day Lillian read a book some Hollywood producer had sent, and she told Horton that he ought to consider this one. The book was Harper Lee’s soon-to-be Pulitzer prize–winning novel of courage and innocence in a small Alabama town, To Kill a Mockingbird. It is a moving, richly intelligent book that was transformed into a moving, richly intelligent motion picture.

It became a classic, one of the masterworks of American cinema. Shot in black and white and mostly indoors, it has an old-fashioned look but a timeless power. It was a tremendous success both critically and commercially, much to the surprise of the Universal Studio executives who thought it boring. They were reluctant to release it, but only Gregory Peck had the clout to control the final edit and to demand the terms of the film’s release. It was nominated for seven Academy awards and won two—for Peck and for Foote—despite nearly overwhelming competition that year from Lawrence of Arabia.

To appreciate Foote’s contribution as screenwriter, it is necessary only to watch The Chase, the bungled attempt to bring to the screen his own fine novel. Producer Sam Spiegel sunk a fortune into it and hired an incredible cast: Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, Robert Redford, E. G. Marshall, Angie Dickinson. Instead of having Foote adapt it himself, though, Spiegel entrusted the job to a Hollywood insider, Lillian Heilman, the caustic author of The Little Foxes.

“Heilman told me she used my work as a point of departure,” says Foote, shaking his head as if to clear the memory. “She definitely departed from it.”

Heilman made obvious everything that he had left ambiguous, turning drama into melodrama. The characters devolved into caricatures, and the actors, taking their cue, overplayed them shamelessly. It was a classic Hollywood disaster.

“I learned a very big lesson,” Foote says. “If you sell your work to a studio, they own it. That’s why I never would do it again. That’s the last time I did it.”

He did his own adaptation of his Broadway hit The Traveling Lady, which became the movie Baby, the Rain Must Fall and was shot on location in Wharton by the same team—Alan Pakula as producer and Robert Mulligan as director—that had done Mockingbird. Here again, studio pressures upset the chemistry of a proven combination. The stage version had focused on a woman who suffers through a marriage to a drunken, mean-tempered man and still survives with her dignity. When the studio insisted on Steve McQueen as the husband—a rockabilly singer, no less—the focus shifted inevitably to him. It became the story of a violent jerk who couldn’t even sing very well, and nobody liked it.

Foote was tiring of the Hollywood studio system by then. As a last resort, he tried working with Otto Preminger, who, Foote believed, had always managed to work within the system and still make good pictures. Preminger recruited Foote to do the screenplay for Hurry Sundown, a best-selling bad novel about noble blacks and greedy whites in rural Georgia. The director and the writer became “quite good friends” in the course of their collaboration, but Foote’s efforts to moderate the book’s fatuous clichés did not suit Preminger’s purposes. It was the heyday of the civil rights movement—1966—and the Austrian-born director sought to make a statement about American racism. Not a single word of Foote’s was used in the shooting script. Even though he is credited as co-writer, he has never seen the movie.

The problem was that, well, the times they were a-changin’. Television had been captured by charming white-bread families and the occasional detective, and the loss of the television audience was forcing movies to emphasize visuals over words. The Day-Glo sixties were gathering force, and the older artists of a calmer America were falling out of fashion. Quickly. “The Broadway that I knew was just collapsing on all sides,” says Foote. “They were using words on stage that I’d never said out loud in my whole life.”

Even his themes went up in smoke. Nearly all of Foote’s works are centered on the struggles of family ties, which suddenly didn’t matter in the liberated, anti-family sixties. Making love free also made it dramatically irrelevant.

Foote took the hint. Instead of fighting the times and looking foolish, he quit writing. In 1966 he moved his family to the hamlet of New Boston, New Hampshire. Because they now had four children to care for, Lillian became a real estate agent. Horton considered dealing in antiques, but she wouldn’t let him. She knew he would be miserable if he didn’t at least try to write, even if he couldn’t get his works produced. Nearly a decade went by in this way. It could easily have been the end of his career. Instead, it was only the end of Act II.

For 42 years, beginning on the day he left home to become an actor, Horton Foote’s mother, Hallie, wrote him at least two times a week, passing on news and opinions and love from Wharton. Several times each year he would return to visit, bringing his own family with him as it grew in number. No matter where he was living or working—in New York or Los Angeles, London or New Hampshire—there was never any question where his real home was. He even purchased the last available plot in the old Wharton cemetery, where so many of his ancestors lie.

Then in 1974 his mother died, barely a year after his father, and Foote journeyed sadly to Wharton to sort things out. The subtle entanglements of blood, the theme that sustained his first career, now called him to begin yet another, even more personal career. They infused his spirit with old hope and new loss, charging his will to embark on a masterpiece or nothing.

The Orphans’ Home Cycle is a roundelay of nine full-length plays, each a complete drama in its own right, all held together by the central characters of Horace and Hallie Robedaux, fictional stand-ins for Foote’s parents, Horton and Hallie. The central thread is a retelling of the life of Horace Senior, from the death of his father in the first play to the death of his father-in-law in the last. There is even a minor character named Horace Junior, who makes his appearance in 1918, the seventh play in the cycle, and who is in fact the fictive incarnation of the author himself. Or the reincarnation.

It is almost too inbred to elucidate objectively. Foote’s daughter, Hallie, for example, has played her own grandmother Hallie in three movies and three Off-Broadway plays. Lillian acted as producer on the films, and two other Foote children—Dixie and Horton Junior—have worked on them or been in them.

This melding of fiction and reality resounds so strongly through the work that only a writer in perfect tune with his talent could hear the voices clearly and set them down plainly. Foote worked on these cycle plays during his long New Hampshire exile in the seventies, listening to Charles Ives records as he wrote, gaining strength as he went along.

He was so rejuvenated that, almost in his spare time, he wrote an Oscar-winning script for his old friend Robert Duvall, whose screen debut, arranged by Lillian Foote, had been in To Kill a Mockingbird. The two men had talked for years about doing a film together, and Duvall, by now a major star, had the industry muscle to make it happen. The film was Tender Mercies.

Mac Sledge, the broken-down country singer whom Duvall plays in Tender Mercies (1983), seems almost a redeemed version of Henry Thomas, the mean-drunk rockabilly singer that Steve McQueen played twenty years earlier. If there is a difference between Foote’s early plays and his later ones, it is the Lord’s small, tender mercies that now grace his sinful survivors, usually in Act III, and that allow their redemption. At the heart of Foote’s later works is a spirituality that avoids religion by exalting faith in all its forms. Although his works have religious overtones, he does not preach through his characters.

The Hollywood game, though, was no different than it had been in the sixties. Foote and Duvall tried to produce Tender Mercies themselves, without any studio support, once the film was completed. Universal was reluctant to distribute the film until the Academy Award nominations were announced. When the movie won best actor and best original screenplay honors, the new generation of studio executives were no less astonished than their predecessors had been.

By this time, Foote was convinced he could make better movies, with less pain and suffering, with no studio involvement at all. Just as he had once helped invent a legitimate alternative to the high-dollar Broadway stage, he now became a father figure for the independent film community, which did much to invigorate American filmmaking in the eighties.

The vehicle for Foote’s cinematic ambition would be the Orphans’ Home Cycle, which was then coming to life on stages around the country. The regional-theater movement had been gathering force since the early seventies, slowly creating a truly indigenous American theater. By the mid-eighties there were Horton Foote festivals from Atlanta to Cleveland to San Francisco, presenting not only his newer works but revivals of his older hits. Horton Foote’s homespun dramas were back in style.

That gave impetus to Foote’s ambition to bring to the screen the entire Orphans’ Home Cycle: nine separate movies with consistent casting to span the years from 1902 to 1928. It was a rather cocky dream. Most independent producers are exhausted just making one movie and getting it released. Not even Hollywood had ever seen a nine-picture deal.

Foote and his family returned to Texas to enlist support for their awesome task. A very modest budget of $1.8 million was raised in Texas, and a small all-Texas crew was assembled that included Dallas director Ken Harrison. The first cycle play to become a movie was 1918 (actually the seventh play in the cycle), in 1985. It was shot on location in Waxahachie with a natural look, a small-town pace, and an honesty that made it very daring, the kind of writer’s film that had gone out of fashion in the fifties.

Vincent Canby of the New York Times, the professional descendant of old Brooks Atkinson, wrote a series of lavish reviews that echoed his eminent predecessor fifty years before:

Much like its small-town Texas characters, Horton Foote’s 1918, directed by Ken Harrison, is a movie of such tight-lipped self-control—and such distrust of fancified melodramatic conceits—that it’s not easy at first to get to know it.

The movie seems standoffish until one finds its rhythm. At that point, what seems to be a conventional if diffident film reveals itself to be a moving, idealized reverie about a time and place and people who, being so resolutely ordinary, become particular. . . .

The film is so purposefully muted that it has the effect—in this age of hyperventilated movie-making—of seeming avant garde.

It was during the final editing of 1918 that Foote received a call from his cousin Peter Masterson, a member of the board of the Actors’ Studio in New York and the co-author and director of the Broadway phenomenon, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Masterson said he wanted to make a movie (his first) out of Foote’s thirty-year-old play, The Trip to Bountiful. Foote said okay, if they could agree on the casting. Luckily, they both had the same star in mind: Geraldine Page.

Carrie Watts—the character Page portrays—is an old woman smothered by indignities in a two-room apartment in Houston that belongs to her weak-willed son and his self-centered wife. The candle that keeps her tired heart warm is the memory of her hometown, Bountiful, which she hasn’t seen for twenty years. One day she slips away to make what she knows will be her final trip home. Her journey lacks the tumult and adventure of Ulysses’, perhaps, but it’s plenty eventful for her, and damn difficult. At one point she despairs of achieving her destination—but then, rising above it, declares: “It’s come to me what to do. I’ll go on. That much has come to me. I’ll go on. I feel my strength and my purpose strong within me. I’ll go on to Bountiful.”

She does too. The fact that the town is deserted and her old house a relic is not what matters. Carrie Watts is tougher than she looks, and she knows that. It is a movie about how to love without losing heart.

The film touched a nerve and found an audience, moving out of art houses to shopping mall multiplexes, where the serious box office is. Its success inspired a boom in independent films, which for a couple of years competed with studio films in the U.S.

It was a brief revolution—the studios quickly hired the new producers and bought their own theaters—but it made Foote a guru to a new wave of offbeat filmmakers. He was even a celebrity for a while, profiled in People magazine. In 1986 he made the New York Times critics’ ten-best lists: with both a movie (Bountiful) and a Broadway play (The Widow Claire, one of the cycle plays).

By 1987 the Foote family had completed filming three of the cycle plays—the middle three—which were run back to back on public television, which had helped finance two of them. Sadly, the fourth cycle movie, Convicts (actually the second play in the saga), is currently frozen in bankruptcy proceedings. It was shot last year in Louisiana and financed with California money that turned into debt for real estate reasons, throwing the film into court. Directed by Peter Masterson, it stars Robert Duvall in a tour de force Lear-like role. Foote and Masterson hope to get Convicts into theaters eventually, though—perhaps as soon as this fall—and then there will only be five plays left to film.

For the past two years Horton and Lillian have been living in Wharton full time, in the house where Horton wrote that first Broadway play more than fifty years ago. The story of the house itself is interwoven, like everything else in his life, in his work. Foote’s parents had been forced to elope because her parents—the rich ones—had not approved of the young haberdasher who was Horton Senior. Horace and Hallie Robedaux find themselves in the same situation in the middle three plays of the Orphans’ Home Cycle. What draws the fictional families back together is the birth of Horace Junior, a reconciliation symbolized by the gift of a new house from the rich father-in-law to the young couple. This takes place in 1918.

“This was the reconciliation house,” says Horton Foote on the front porch. Since his return to this house, he has written another six plays, including some for television and another—maybe—for the movies. His most recent play, Talking Pictures, was first presented in Houston in May at Stages Repertory Theatre, directed by Peter Masterson.

Foote squirms in his seat a little; he gets uncomfortable discussing the themes of his work. “I suppose you’d have to say I’m attracted to survivors,” he finally says. “I’m a survivor. At the same time, I have great compassion for those who don’t survive in life. My heart has been broken many times by people I loved who couldn’t find a way. And I don’t know what the difference is, what gives some people the strength to go on. I can only be in awe and wonder that certain people have it.”

Now that he is back in Texas, Foote is finally getting the local recognition he deserves as a Gulf Coast Chekhov. In May the Houston City Council officially proclaimed a Horton Foote Day, and Conoco underwrote a lavish black-tie testimonial dinner at the Alley Theatre, where Foote was presented with the 1991 Alley Award. Visiting dignitaries ranged from Jim Lehrer, the public-television news anchor, to Jean Stapleton, the former Edith Bunker, who made her professional acting debut as a bit player in the original Broadway production of The Trip to Bountiful. There were flattering telegrams from George Bush and Gregory Peck, and dramatic readings from Foote’s works.

The most revealing moment, though, was when Peter Masterson told a story about the filming of The Trip to Bountiful. “The money people,” as Masterson described them, had been steadily pressing him to talk to Foote about a new ending, a more upbeat one that allowed Mrs. Watts to live happily ever after in Bountiful, instead of returning to her dreary life in Houston.

“That’s the ending that the audience might want to see,” Foote had told Masterson when he finally brought it up. “But it’s not the ending that’ll break their hearts.”

“I didn’t realize how tough he was,” Masterson told the audience.

The toughness was only a front for his integrity, of course. Heartbreak, after all, is a true fact of life, and everybody knows it. As Mrs. Watts herself knows, you can’t deny reality and survive. It was enough just to get there, to accomplish her purpose. It doesn’t bother her that the town has disappeared.

“The river will be here,” she says. “The fields. The woods. The smell of the Gulf. That’s what I always took my strength from . . .”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Film