This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

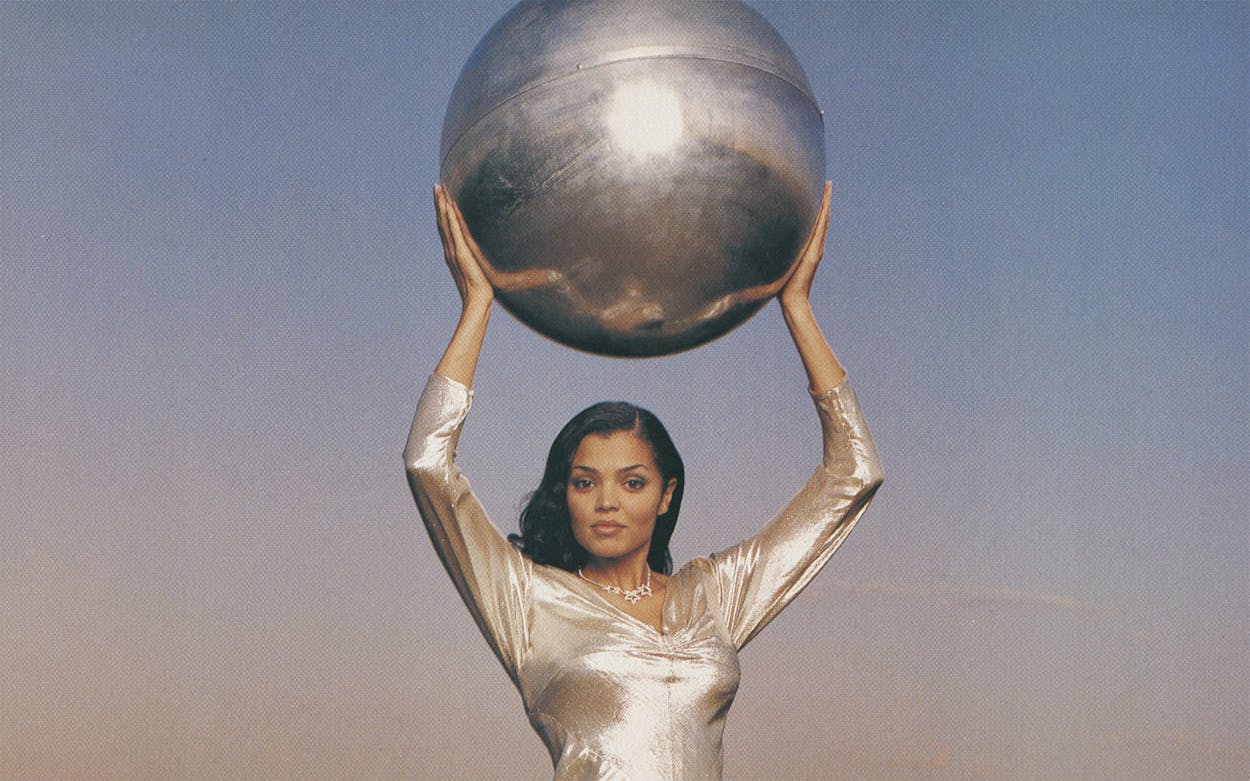

There isn’t much that is beautiful to look at in Deer Park, the pastorally named petrochemical suburb east of Houston and the hometown of Miss Universe 1995, Chelsi Smith. Appearing last May at a celebration in her honor, Chelsi, who likes to be known as the first biracial Miss Universe, looked less like a conventional beauty queen than the kind of computerized composite of multicultural beauties favored by news and fashion magazines these days. Striding down a red carpet in Deer Park’s corrugated-metal civic center, the 21-year-old wore the generous smile that reproduces so well in photographs; her hair and eyes were dark and glistening, her legs longer than a Houston summer, and her skin that indeterminate but robust shade known as tawny. High school friends embraced her proudly, little girls presented her with flowers, and little boys hugged her around the hips. A single African American teenager eased her way through the crowd of white faces, admiring Chelsi but appraising her too. “Seeing y’all is just so cool,” Chelsi told the crowd, and she meant it.

But Chelsi has already left home in the way of so many beauty queens, her looks having provided an escape route from all the realities that make her representative of her time. There was the childhood that was both motherless and fatherless (she was raised by her maternal grandparents); there was the desire for racial identity. Though Chelsi likes to say that she belongs to both races, her exposure to the African American culture of her father has been limited—she hardly sees him or his family—and the white schoolmates she grew up with were not always color-blind. She vividly remembers flirting with boys at the mall one afternoon in the company of her friends. “The only guys they would point out for me to date were black,” she says. “I thought, ‘Well, who allowed you to choose for me?’ ” Then there was the hardness of life in Deer Park, where many people grow old before their time, where Chelsi’s ambition to enter the entertainment world was eventually replaced by the more realistic goal of a career in elementary school education. It was, in fact, Chelsi’s desire to attend a four-year rather than a two-year college that led her to go after the prize money offered by the Miss Texas USA pageant. “I knew my mental capacity could surpass what I had in a swimsuit,” she says.

So now her life consists of the nice apartment in a tony Los Angeles neighborhood (“Like the Galleria area times a hundred”), the meetings with Quincy Jones, the motivational speeches, the personal trainer, the agency that wants to ease her into broadcasting. There is also the $200,000 Miss USA prize money she won in February, as well as the $200,000 Miss Universe prize money, along with the elephant named after her in Namibia, Africa, where the pageant was held. And so, the girl who was always careful to say hi to everyone in high school has won a place in that world of celebrity where there is no poverty, no history, and no color, only fame and fortune.

“Chelsi! My daughter’s scrapbooks are overflowing with you! Keep up the good ambassadoring!” a friend wrote. “We are proud of you! You have already brought great honor to Deer Park!” said another. They were happy for her, but happiest of all to let her go.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Houston