This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

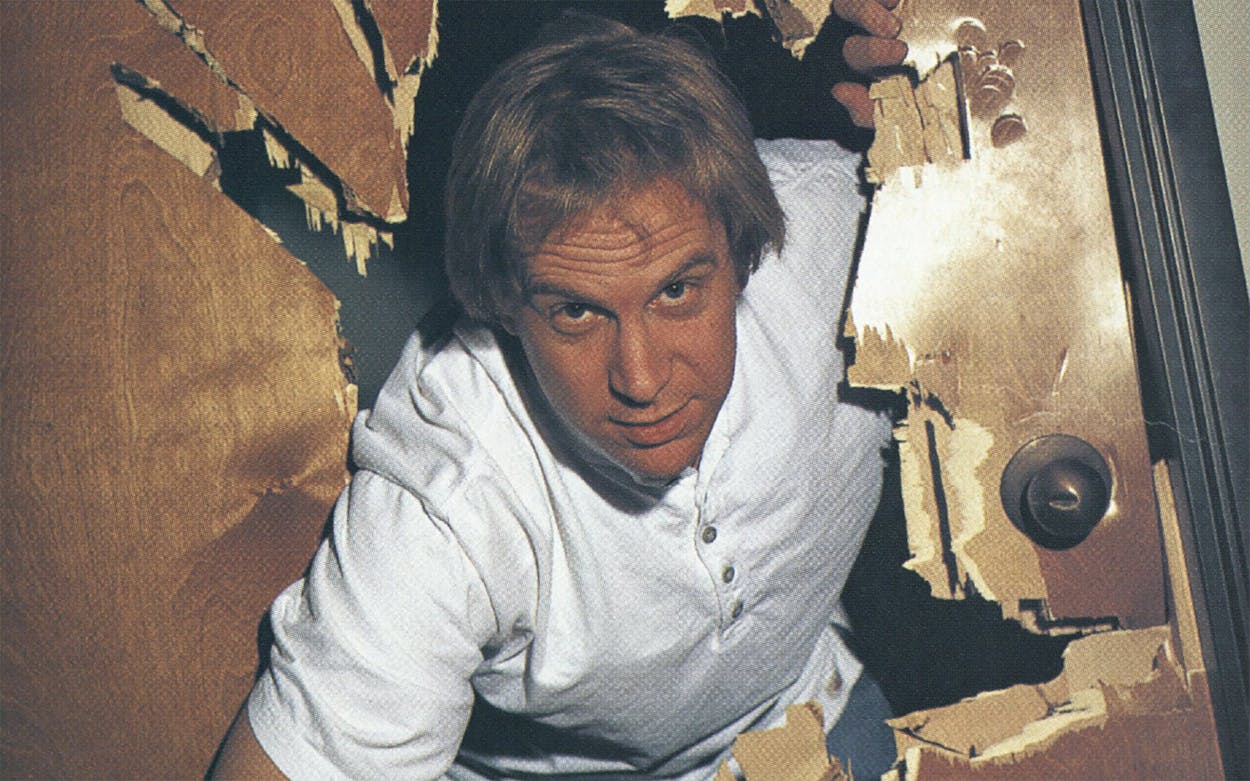

In a year when everyone from parents to the president of the United States is blasting violence in entertainment, computer games mogul Jay Wilbur is digging in his heels—and hitting the family values crowd where it lives. Ask the 34-year-old CEO of Mesquite’s id Software about the gory content of his best-selling titles, Doom and Doom II, in which players navigate three-dimensional rooms and shoot or vaporize assorted mutants and monsters, and he turns the criticism on its head. “We have had our fair share of religious friends ask us about our imagery, which is satanic,” he admits, “but they overlook the object of the game. The player is the good guy in white whose job it is to stop demons, and you have to travel to Hell to do it. Do you have a problem with stopping Satan from doing his dirty work? Which side are you on?”

It’s a great line, but more than that, it’s indicative of the subversive attitude and unconventional approach that have brought Wilbur and id Software to the top of the computer games business. The eleven-person company logged $10 million in revenues in 1994 and hopes to reach $20 million this year. What’s more, a movie version of Doom, to be produced by Ivan Reitman (the director of Ghostbusters), is in development at Universal Studios; Doom merchandise (T-shirts, trading cards) is selling like rock band memorabilia; and Pocket Books will soon release the first two titles in a Doom paperback series. “Pinch me,” Wilbur says with a laugh. “Am I awake?”

The success story began four years ago in Shreveport, Louisiana, when four techies in their twenties—Tom Hall, John Romero, John Carmack, and Adrian Carmack (no relation)—left the software company they were working for and founded id. A year later, after moving id to Mesquite, they were joined by two former colleagues: fellow techie Kevin Cloud and Wilbur, the self-described “biz guy,” who took over as the company’s chief executive. In 1993 the group produced its first big game, a space-adventure shoot-’em-up called Commander Keen, and then developed the groundbreaking three-dimensional graphics on display in its next effort, Wolfenstein 3D, in which the object was to kill evil Nazis. Later that year, Doom was unveiled and immediately became a runaway hit—to date, the game has been installed on at least 15 million computers worldwide. In 1994 id released both Doom II (which as of this July was still the fifth-best-selling CD-ROM in the country) and Heretic, a Doom-like game set in medieval times.

The key to id’s success has always been to keep traditional notions of business out of the equation. For one thing, its corporate structure is horizontal rather than vertical: Wilbur may be the titular CEO, but he runs the big decisions by Carmack, Romero, Carmack, and Cloud (Hall left the company last year to pursue other interests). For another thing, id’s sales strategy, as one software industry observer notes, is similar to the distribution schemes of street-level drug dealers: The first levels of a game can be downloaded or copied for free, in the hope that a user will get addicted and buy the advanced levels.

Most important, Wilbur says, the partners try not to think about the bottom line. “At most game companies, the people in the trenches developing games are the ones with passion, but they’re driven by bean counters looking at numbers on their little white pads. Or the bean counters are driven by the legal department, which says, ‘You know, we really can’t have this devil thing. There’s a PTA group out there that’s gonna come down on us.’ We approach our business as game players first. The only question that needs to be answered is, ‘Is it fun?’ ”

To those who might rail against the way id’s creations romanticize violence, Wilbur says, “These are the same games we used to play when we were kids, pointing a stick at someone and going, ‘Ka-pow, ka-pow’—the bang-bang Army stuff. The only difference is that the technology makes it cooler.” And never mind what message the games are sending to kids. “If parents take an active role in their child’s development, a game like Doom will not cause him to turn into a nut case,” says Wilbur, whose five-year-old son, Josh, enjoys sitting on his lap and watching him annihilate the deadly attackers.

Anyway, all Wilbur and his team care about is the future—specifically, the fall release of Heretic II and the Christmas debut of Quake, which promises even more techno-realism than Doom by allowing players to look up and down as well as all around. “Our passion isn’t just to develop the greatest game in the world,” Wilbur insists, “but to make it so irresistible that when we’re done, we want to play it too. As someone once said: ‘It ain’t bragging if you can do it.’ ” The Doom dudes are doing it like nobody else.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Mesquite