When antiques seekers begin filing into Round Top later this month for the world-famous Antiques Week, they may notice that the tiny Fayette County hamlet looks quite different from the way it did a few years ago. Round Top—at 640 acres, one of the smallest towns in Texas—is undergoing an unlikely real estate boom.

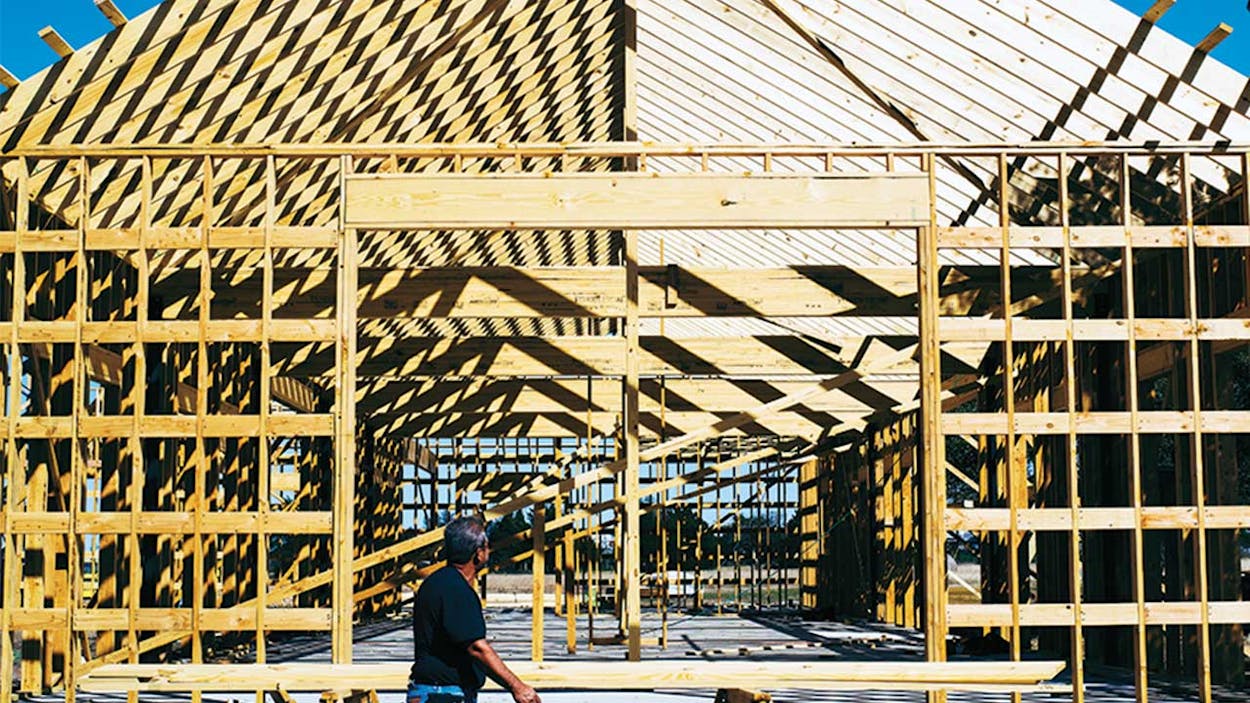

On a recent sunny Tuesday, construction crews are raising buildings and refurbishing entire blocks of the town. At centrally located Rummel Square, eight historic buildings have been positioned around a towering, five-hundred-year-old live oak. When the renovation of those structures is complete, the square will have a coffee shop, a cigar and liquor store, a farm-to-table restaurant, and, of course, five antiques shops. Not far away, Bybee Square is also undergoing a makeover and will house still more shops and restaurants. And just south of those projects is the Compound, where crews are pouring the slab for a nine-thousand-square-foot building that will be part of an events center capable of handling five hundred people and housing everything from car shows to concerts.

That may seem like a lot of development for a town with just ninety people, but the population number on Round Top’s city limits sign is misleading. Though the town itself is still home to a small cluster of modest, wood-framed houses, the hills surrounding Round Top are in the midst of a high-dollar home-building frenzy, thanks to wealthy weekenders and urbanites seeking a more laid-back lifestyle. One of them is former governor Rick Perry, who in 2013 bought ten acres just outside of town and built a six-bedroom house overlooking the rolling pastures and catfish-filled stock pond of neighbor and longtime friend Tommy Orr, a ten-year resident. Recently, Perry was seen dining with Ted Cruz at Las Patrones Mexican restaurant and buying nails at Round Top Mercantile.

Many locals are dividing up large ranches and selling off two- or three-acre plots to the growing wave of new arrivals. “Most of the people who are coming are looking for small acreage,” says Cathy Cole, the president and CEO of Heritage Texas Country Properties. Home prices average $799,000, and farm and ranch properties in the surrounding areas run as much as $8 million.

Custom-home builder Lewis Tindall says he has been swamped with orders from people coming from the Houston, Austin, and Dallas areas. Over the past five years, his revenue has increased approximately 50 percent. In a first for him, he’s turning away customers because he can’t keep up with the demand.

All that growth on the outskirts is helping to drive a development boom in town that’s intended to encourage more tourism. “People associate Round Top with antiques, but it’s not been year-round,” says developer Mark Massey, who’s heading up the Rummel Square and Compound projects. “We’re trying to make Round Top a year-round destination. In six months it will be a different town.”

Round Top, which was founded in 1826 (it was originally called Townsend), has always been something of a cultural center. In the nineteenth century, for example, it had a prominent string band and was home to Clara Rummel, who was known as the “poetess of Texas.” That legacy continues to this day; there are frequent classical concerts at the world-renowned Festival Hill Concert Hall, which has some of the best acoustics of any venue in the country, and the annual Shakespeare festival in nearby Winedale is only a seven-minute drive away.

What really put Round Top on the map, though, was Antiques Week, which started 48 years ago as a small gathering and now consumes the town and several neighboring communities twice a year, in the spring and fall. As many as 150,000 people are expected to flood into the area late this month, clogging both lanes of Texas Highway 237 and choking parking lots beyond their capacity.

The event’s success has created a full-time home decor industry. Antiques are everywhere in Round Top, and just south of downtown is the “world headquarters” of country kitsch purveyors the Junk Gypsies (sisters Jolie and Amie Sikes), who have their own show on HGTV. Round Top is also one of the few places—San Francisco, New York City, Tokyo, Santa Monica, and London are the others—that are home to a branch of Rachel Ashwell Shabby Chic Couture, a high-end home furnishings store. Lodging may be Round Top’s second-biggest industry after antiques, with dozens of bed-and-breakfasts in the area. Later this year, the Gypsies’ first venture into the lodging industry, the Wander Inn, will open next to their store.

The engine for the most recent spurt of growth is Massey, a 35-year-old Houston native who frequently visited his grandparents in Round Top when he was a child. Three years ago, while he was living in Los Angeles, he, his parents, and his brother decided to buy the historic Henkel Square in the town’s center. The square’s buildings had been transported there, mostly from nearby towns, in the sixties by Houston philanthropists Charles and Faith Bybee, who also assembled much of Bybee Square. Until recently, the Henkel buildings served as a museum for the Bybees’ collection of pioneer antiques; the Masseys are now renting them out as shops and galleries. The Masseys also built Henkel Hall, a facility for weddings that sits adjacent to the Haw Creek Church, a clapboard chapel built around 1872. Based on Henkel Square’s success, Massey decided to sell his West Coast condo, buy the land for the Compound, and move into his grandparents’ farmhouse. “A two-bedroom, two-bath condo in L.A. gets you fifty-seven acres here,” he says.

Massey is striving to make sure that all this growth is done with an eye on maintaining Round Top’s small-town charm, which is, after all, what draws most people here in the first place. (Round Top reportedly hosts the oldest July Fourth parade west of the Mississippi.) “I came home to put my real estate skills to use to benefit the town,” he says. While town leaders have generally supported development, they have adopted strict building codes and architectural standards to preserve the historic structures and statuesque oak trees. Like many historic hamlets, Round Top has ordinances to keep out chain restaurants—no Subways or Dairy Queens or Starbucks. Massey and his tenants are betting that locally minded establishments will enhance Round Top’s appeal as a year-round destination.

The growth in home buyers and businesses is helping Round Top fend off the fate that has befallen many small towns without major employers. Across the country, rural areas are struggling to keep people. Between 2010 and 2013, six in ten rural counties registered population losses, compared with less than half that in the mid-aughts, according to a study by the Brookings Institution. In Texas that trend has been more pronounced because of the decline in single-family farming and ranching, hastened along by recent droughts. Even at the peak of the oil boom, rural areas lost people to Houston and the big cities along Interstate 35. The one exception is small towns that can create a niche market for tourism, says Jason Draper, who teaches tourism classes at the University of Houston’s Conrad N. Hilton College. That isn’t as easy as it sounds. “Tourism is a very complex thing,” Draper says. “You have to have a sound plan and know how to develop and how much to develop.” The antiques fair, he says, gives Round Top name recognition it can build on.

The transformation of Round Top into the Aspen of Texas may be a boon for developers, tourists, and newcomers, but it’s a mixed bag for the locals. On the one hand, they can sell their properties at a hefty premium. Roy Wied, a longtime Round Top resident who converted his cow pasture into Bar W Antiques & Collectibles, says the boom has benefited the families of longtime residents who are dying off or looking to sell their properties. And the growth is helping fill the town’s coffers: sales tax receipts jumped by more than 50 percent in the past three years, according to the state comptroller’s office.

On the other hand, locals run the risk of being priced out of town by higher taxes, as happened in Marfa when wealthy Californians swooped in and began buying land. “Once the ball gets rolling, there’s a lot of people who will be interested in speculating on the land there,” says Bill Gilmer, the director of the Institute for Regional Forecasting at the University of Houston.

And balancing small-town charm with a development boom isn’t always easy—or peaceful. Complaints from nearby residents about noise from the Stone Cellar pub prompted a lawsuit from the town, which was eventually withdrawn; owner Jon Perez decided to book quieter bands. In the old days, the various parties probably would have resolved the dispute among themselves, without complaining to the city or invoking legal action. “That’s part of the old coming together with the new,” Gerald Tobola, a local art gallery owner, says. “People are no longer able to just work things out.”

Other small towns in Texas—think Fredericksburg or Boerne a decade ago—have experienced artisan booms and the influx of city folks looking for a piece of the country. But most of them are larger towns connected to bigger cities by major highways. Round Top is isolated, linked to U.S. 290 to the north and Interstate 10 to the south by the lonely stretch of Highway 237. You don’t come across it by accident.

While that isolation is a selling point, it doesn’t insulate the town from the vagaries of the economy beyond its lush rolling hills. Much of the area’s growth is tied to discretionary spending—weekenders looking for everything from homes to knickknacks. With oil prices dipping below $30 a barrel in mid-January, and with the loss of 30,000 oil-industry jobs in Houston last year, cash-strapped Houstonians might stop coming to spend money on tchotchkes and sculptures. Tobola—who, incidentally, came to town ten years ago after losing his job in Houston—estimates that 60 percent of his customers have some connection to the oil and gas business. “It’s most definitely affecting us,” he says. Round Top’s soaring sales-tax growth slipped more than 11 percent in January compared with a year earlier, but receipts remain well above previous years. Tobola points out that Round Top’s location makes it an affordable getaway: people who are watching their budget might cancel that pricey trip to Cabo and drive out here instead.

As I leave Tobola’s gallery and turn onto the main road to head toward Houston, I confront more evidence of Round Top’s recent growth: new stop signs outlined with blinking red lights, the sort of thing you see at particularly busy or dangerous intersections. At this moment, there’s no traffic in any direction. But if Massey has his way, there will be soon.