Daybreak was still more than an hour away on the morning of September 28, 2003, when Cass County sheriff’s deputy John Elder turned down Old Dump Road. Above the tree line, the sky was moonless and dark. Cass County is pressed deep into the northeastern corner of Texas, hard against the Arkansas and Louisiana state lines, and it is crisscrossed by back roads that meander into the woods, under pine awnings and over low-water crossings and past unincorporated communities not found on maps. Elder followed the blacktop as it tacked back and forth, and after roughly a mile, he spotted a silver pickup idling at a T in the road. Two young men who had called the sheriff’s department were sitting inside. “He’s over here,” the driver called out, motioning for the deputy to follow him. Elder fell in behind the pickup as it headed to the left, down a county road that had few houses or mailboxes or signs of life.

They came to a stop after half a mile, and Elder could make out a figure on the ground, huddled in the fetal position. He was a short, slight black man, and he was wearing only a T-shirt and jeans despite the cool weather. Elder knelt down, and after fishing the man’s identification out of his pocket, the deputy saw that he was Billy Ray Johnson. Around Linden, the county seat, Billy Ray was often seen hanging around the courthouse square or walking by the side of the road, and he was what people in town politely called “slow.” Elder could see that he was alive but in bad shape. The bottom half of his face was bruised and swollen, and his breathing sounded labored. His upper lip was cut, and blood had pooled on the ground under him. His entire body had been badly stung by fire ants. The deputy tried to wake him, but Billy Ray was unconscious.

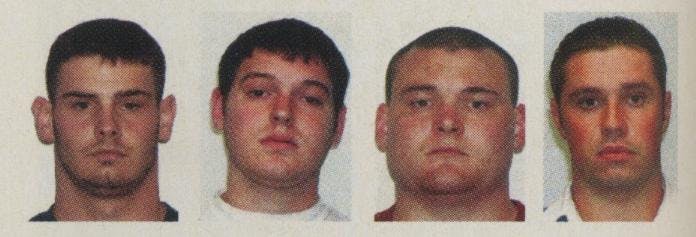

Elder called for an ambulance and then inspected the pavement, searching for evidence of a hit-and-run. But he found no skid marks or broken glass, and so he turned to the two white men who had led him out there to ask them what they knew. Elder recognized the bigger, heavyset one with the crew cut as 24-year-old Corey Hicks, who had served in the Navy and now worked at the sheriff’s department as a jailer. Elder wasn’t familiar with Corey’s friend, 19-year-old Wes Owens, who stood with his hands in his pockets and said little. “Now, how did y’all find him?” Elder asked.

Corey shrugged. “We were just riding around,” he said, explaining that they had been at a party until early that Sunday morning. “We drove up on him and saw him laying there.”

Elder nodded and didn’t probe further. Billy Ray smelled of alcohol, and in the absence of any evidence of a hit-and-run, the deputy guessed that the 42-year-old had been out walking and had hit his head when he passed out. The two young men who had led him there were nothing if not helpful; when the paramedics arrived and loaded Billy Ray’s limp body onto a gurney, they helped lift him into the back of the ambulance.

But by the following morning, Billy Ray had yet to regain consciousness. A CAT scan found that he had suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage, a serious brain injury that can be caused by blunt force to the head. While he lay in a coma, word spread that he had last been seen Saturday night at a pasture party with some white boys half his age. Still, the sheriff’s department did not grasp that it had a criminal investigation on its hands until Lieutenant Ray Copeland, the department’s chief investigator, began receiving anonymous phone calls—three that week, all from what sounded to him like the same soft-spoken white man. “Y’all need to look into what happened to Billy Ray,” the caller said, and hung up.

What the investigation unearthed was a story that no one in Linden wanted to believe: Billy Ray, who is mentally disabled, had been taken to a party, ridiculed, called racial slurs, knocked unconscious, and then dumped by the side of the road. Even the strangers who had come to his aid were not Good Samaritans but two of the perpetrators. Had the town’s white residents condemned what had happened to Billy Ray, the incident might have faded into memory; the crime pivoted on a single punch. Instead, they closed ranks, and juries in both criminal trials that followed declined to give the defendants more than a slap on the wrist. Now Morris Dees, one of the nation’s preeminent civil rights lawyers, has taken up Billy Ray’s case, and Linden—a place most Texans have never heard of—will likely become the focus of national attention when the wrongful-injury lawsuit goes to trial this spring. Whether a new jury will see things differently depends on how Linden perceives its own role in this drama: as a community that must redeem itself or as a small town unfairly maligned by outsiders.

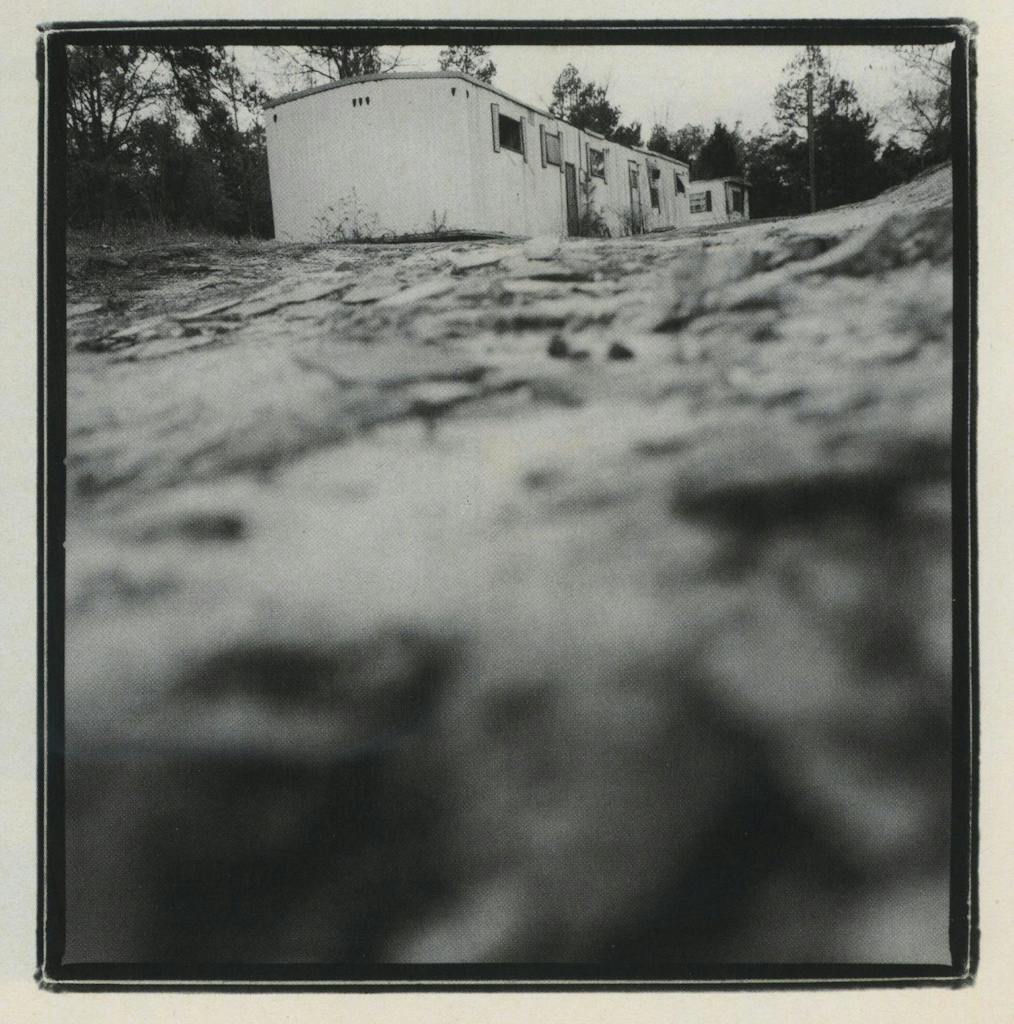

BILLY RAY GREW UP LESS THAN TWO miles from where he had been found, in a sagging white trailer on Old Dump Road. He was raised by his widowed grandmother, Era Lockett Taylor—Miss Era, as she was called—after he was born with meningitis to mentally disabled parents. Billy Ray had five brothers, two of whom were also mentally disabled. (Relatives and neighbors raised all but the youngest son, Bonnie.) As a boy, Billy Ray was able to grasp simple concepts his mother had never mastered, like how to dial a phone number or pay for something in a store, but he couldn’t learn to read or write, and he was often the butt of other kids’ jokes; on the school bus, his cousins handed over their lunch money to his tormentors so he would be left alone. After he had to repeat the fifth grade, Miss Era pulled him out of school for good, and they lived in the woods, apart from the world, for more than twenty years.

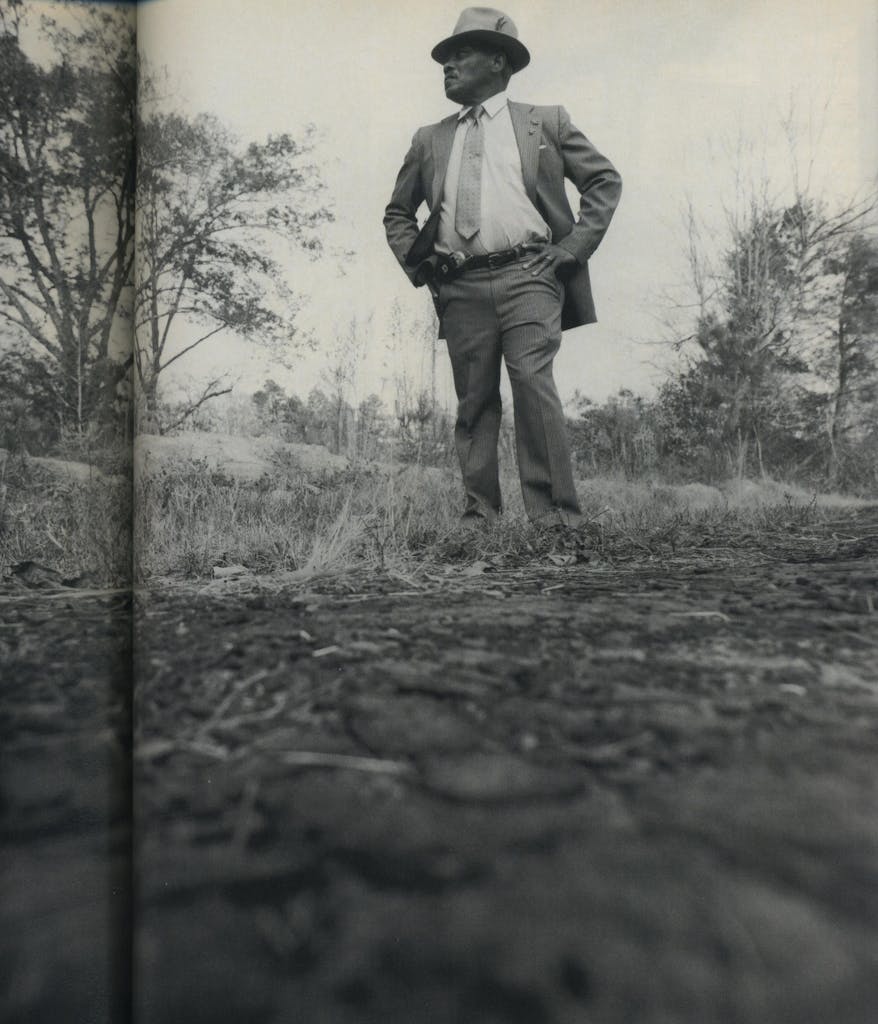

Miss Era discouraged anyone from bothering Billy Ray by keeping a 12-gauge shotgun propped beside the door. (A light pole on her property, which is pitted with lead shot, attests to her vigilance.) “No one messed with Billy Ray while Miss Era was alive,” said his cousin Lenda Beachum. “We were all scared to death of her. If she said, ‘Jump,’ we asked her, ‘How high?’” Even as an adult, Billy Ray came into town only when Miss Era needed to pick something up at the store, and when she did, he would sit quietly in the passenger seat, gazing out the window. “Everybody always thought he was a nothing and a nobody,” said his cousin Lue Arthur Wilson. “I felt sorry for him being stuck out there all by himself. I used to stop by with my guitar and play music for him—he liked Lightnin’ Hopkins and Jimmy Reed and Elmore James. I’d play until Miss Era would say, ‘Billy Ray, ain’t you tired of hearing that fuss?’ And then I’d have to get going.”

Billy Ray’s transistor radio was his constant companion, and each day he sat on whichever side of Miss Era’s trailer allowed him to pick up a stronger signal. He liked to slide on his sunglasses and listen to the R&B stations out of Shreveport and Tyler; at night, he picked up shows that were beamed in from faraway places like Nashville. Though life with Miss Era was tightly circumscribed, he had his own way of traveling beyond Old Dump Road. His grandmother’s property was littered with the skeletons of half a dozen or so gutted, rusted-out cars, and he spent hours tinkering with them and taking his favorite ones out for test drives. Sitting behind the wheel, he would steer as if he were flying down the highway. He seemed not to care that the car he was driving had no transmission and was jacked up on concrete blocks in the middle of Miss Era’s pasture.

Billy Ray lived with Miss Era until 1995, when she died of cancer and he found himself, at 33, on his own. “She was all he knew,” said his younger brother James. “He’d never been out in the world, never been with people his own age. He’d never had a drink until Miss Era died.” Billy Ray stayed for two years in James’s rent house and then moved in with his mother, who was living in a public housing project a few blocks from the courthouse square. Free to go where he pleased, he spent his days walking around town, nodding and smiling at strangers, but without Miss Era to look after him, sometimes he was at loose ends. A sandwich might be his only food for the day, or some peanut butter straight out of the jar. He bought a snappy new suit with one of his disability checks, but he didn’t understand that it needed to be cleaned, and he wore it again and again until he looked like the homeless person that many people in Linden assumed him to be.

On the weekends, Billy Ray helped out at his cousin Lue’s honky-tonk, the Bee Hive, a black club on one of Linden’s back roads where patrons brought their own coolers and anyone was welcome to play the blues guitar. Billy Ray swept floors and picked up empty beer bottles and largely kept to himself, and yet customers enjoyed laughing at his expense. “People thought it was funny to make an ass out of him,” Lue said. “They’d say, ‘Come on, Billy Ray, you going to dance tonight?’ And so he’d stamp his feet and stick his neck out and shuffle around for them. He couldn’t dance, but he loved the attention.” At the projects, Billy Ray was an even easier mark. “He was real popular once a month when he got his disability check,” Lue said. “Women would sweet-talk him, crackheads would hit him up for loans. They’d say, ‘Can I borrow some money and pay you back tomorrow?’ Billy Ray didn’t know no better. He was everybody’s friend.”

One afternoon in October, Lue took me to the house on Nelson Street where Billy Ray had been living with his mother in September 2003—a gray, dilapidated frame house where two days’ worth of rain had turned the hard-packed dirt yard into a pool of mud. It was still home to Billy Ray’s mother, Lizzie Mae Stephenson, who was slumped inside on a faded flower-print sofa, her body folded into its cushions. She was a small, frail woman in her seventies, and she did not seem to notice when we came in. The house was illuminated by a single bare bulb, and the rooms looked as if they had not been cleaned in years. Unwashed clothes were piled in heaps on the floor, and half-eaten plates of food rested on the kitchen counters. Roaches climbed the walls and skittered across the dining room table. Lizzie sat, staring at the wall, loudly humming a weird, gloomy tune. Her son James’s girlfriend, Tina Thomas, had stopped by to check in and was trying to engage her in conversation, to which Lizzie at last responded with a few low, guttural sounds. She looked around the room, and when her eyes focused on me, a stranger, she looked frightened. She lifted herself off the couch and hurried into the bathroom, locking herself inside.

Lizzie, the family told me, had not been mentally disabled at birth. When she was an infant in Sulphur Springs—a little more than an hour’s drive west of Linden—her parents, who were itinerant sharecroppers, had been coming back from church one Sunday when a group of white teenagers started throwing rocks at them. Lizzie was struck on the head, over her left eye, and the impact had cracked her skull open. She was forever changed, according to her sister Essie Lee Pryor; as a child, she was unable to do even menial work, and when the rest of the family picked cotton, she sat and watched. Even the children Lizzie went on to have who were not mentally disabled had never known a normal life. One son is currently in prison for aggravated assault; another was murdered in 1995. As I listened to Tina try to coax Lizzie out of the bathroom, I wondered how her life—and Billy Ray’s—might have turned out if not for the cruel trajectory of one rock.

When Lizzie emerged, she sat down beside me, and I explained that I was working on an article about Billy Ray. At the mention of his name, she covered her face with her hands and began to cry out, “My son, my son, my son …”

THE PASTURE PARTY HAD ALREADY gotten under way that Saturday night when Wes Owens eased his pickup away from the bonfire and headed for the Country Store to buy some snuff. Wes was everything that Billy Ray was not. He was from an influential Linden family and had been a popular varsity football player in high school. But in a small town like Linden, which has 2,275 residents, even the most divergent lives are somehow connected, and when Billy Ray ambled into the Country Store that night, he and Wes stopped to shake hands. Their families had been acquainted for a long time; Billy Ray’s father and two of his brothers used to work summers picking peas and hauling hay on Wes’s grandfather’s farm. The Owenses had given the Johnsons food and secondhand clothes over the years, and Wes had sometimes offered Billy Ray rides around town.

As they stood and talked that night, Billy Ray wore his usual lopsided grin. And then Wes—“the life of the party,” according to friends, a guy who liked to be the center of attention—had an idea. He casually mentioned that he had invited some people to his father’s place up the road, and he asked if Billy Ray wanted to join them.

Billy Ray shook his head. “I’m waiting on a ride,” he said.

“I’ll bring you back up here when your ride’s supposed to be here,” Wes offered. Though Wes had never invited him to a party before, Billy Ray was not in the habit of questioning things. He agreed and climbed into Wes’s truck.

Wes drove less than a mile up the road to his father’s property and turned into a wide, grassy pasture where pickups were parked in a circle around a bonfire. According to court documents and police records, it was after midnight when they arrived, and about a dozen people were sitting on their tailgates drinking beer. When they looked to see who Wes had brought from town, they burst out laughing. One girl overheard twenty-year-old Colt Amox snicker, “Wes has a crazy nigger with him.”

Wes would later say that he had never intended for Billy Ray to become the night’s entertainment, but from the moment they arrived, the joke was on Billy Ray. Wes introduced him to his friends, making up nonsensical names for them as he went. Colt was “Bolt,” while others were “C’mon,” “We-pee,” and “Casey Macaroni.” Guileless, Billy Ray nodded and told each of them, “You can just call me Bill.” Wes turned on some music and handed Billy Ray a beer, and soon he had Billy Ray dancing to Lil’ Kim’s “Magic Stick.” Wes passed an imaginary stick back and forth to him while the group looked on and laughed. When the fire began to fade, Wes had him unload wood from the bed of his truck, and the errand became a game to see how much firewood he could pile on as he raced to and from the pickup. “Come on, Billy Ray, you can get more than that!” people shouted. Someone suggested that he reach into the fire and pull out one of the burning logs, and as Billy Ray bent down to comply, Wes stopped him. “Don’t be stupid,” he said.

The teasing had started to make some people uneasy, and before long, more than half the group decided to go home. Erica Hudson, a freshman at Tyler Junior College, told Wes as she was leaving, “It’s not right.”

Corey Hicks, who had recently gotten off work at the jail, drove up as the party was thinning out. He lived with Wes’ sister, with whom he had two children. When Corey arrived, he turned to a heavy-lidded eighteen-year-old named Dallas Stone. “Why did Wes bring this stupid nigger out here?” he asked.

Dallas shrugged. “For a joke,” he said.

Only six people remained at the party, including Billy Ray, and everyone was drinking heavily. As the night wore on, a pretty twenty-year-old student named Lacy Dorgan—the only woman left at the party—wandered off to throw up, and Wes followed her. The dome light inside her Mustang was on when she and Wes started having sex a few minutes later, and Corey watched them from a distance.

Bored and drunk, Corey, Colt, and Dallas nursed their beers while Billy Ray sat alone by the bonfire. Dallas would later claim that Corey said, “I wish someone would beat this nigger up.” Corey was known for using incendiary language when it came to blacks, and several years earlier he had started a fight at a party with six black men in which he did not come out the victor. He couldn’t beat up Billy Ray himself, he told Colt and Dallas, or he might lose his job, but he thought someone else should. After some goading, Colt agreed to do it, and the three friends all started to laugh. (Colt denies making this pledge.)

Until that point, rap music had been playing, but Colt switched it to country, which elicited complaints from Billy Ray. “If you don’t like the music, you can go,” Colt told him.

“You’d better leave, before the KKK comes and gets you,” Dallas taunted him.

Billy Ray seemed to think they were joking, and he laughed along with them. “I’ll go after I finish my beer,” he said.

Dallas knocked the beer out of his hand. “You’re finished now,” he said.

Wes had dashed up, pulling on his pants as he ran from Lacy’s Mustang, but it was too late. Colt, who had been a pitcher at Linden-Kildare High School, took a swing at Billy Ray, hitting him squarely in the face. He delivered a knockout punch. Billy Ray fell to the ground and stopped moving.

For nearly an hour the group debated what to do as Billy Ray lay a few feet away from them, unconscious. Wes thought they should call an ambulance, and both Dallas and Lacy offered to drive him to the hospital. But Corey overruled them and began barking orders. He did not want the police involved, he said, because his job was on the line. They were going to take Billy Ray to a back road and leave him there, he insisted, assuring the group that he would eventually wake up and walk home. At one point during the discussion, Wes grabbed Billy Ray and lifted him to his feet, trying to make him stand up on his own. When his legs would not support his weight, Wes let him go, and he fell backward, hitting his head on the ground. Finally they loaded him into the bed of Colt’s truck, and Corey led the way while the others followed. Rather than driving a mile north to the hospital, he headed in the opposite direction, toward Old Dump Road. Wes thought Billy Ray might still have some family out there, but they decided against leaving him near a house for fear that someone might see them.

As Corey drove, he asked Lacy, who was riding with him, if she would sit closer. He and Wes’ sister were having problems, he confided, and he had liked her for a long time.

“Why did this happen?” Lacy asked, changing the subject. “Why?”

“Because he’s a fucking nigger,” Corey said.

They turned off Old Dump Road, down County Road 1620, and unloaded him onto the road’s shoulder. From there, Colt drove to the car wash in Linden, where he cleaned blood and vomit out of the bed of his pickup. Panicked, Dallas drove to a friend’s house and woke him up to tell him what had happened; then he ran to the bathroom and got sick. Wes went to Corey’s house, and they decided to drive back to check on Billy Ray. He was still breathing, but they could see he was bleeding from his mouth. Almost two hours had passed since he had been knocked unconscious, and they wondered if he might be dying. Corey called the sheriff’s department on Wes’s cell phone. “There’s a black man out here on the side of the road,” he said. “He must have got drunk and fell out.”

THE INVESTIGATION DID NOT BEGIN in earnest until that Thursday morning, four days after the attack, when Lieutenant Copeland sat Corey down to ask him a few questions after he finished his shift at the jail. When Copeland asked him to describe what had happened early Sunday morning, Corey recounted what he had already told Deputy Elder—he and Wes had been riding around when they came across Billy Ray—and he expressed concern for the stranger’s welfare. “Do you know how he’s doing?” he asked, adding that he had called the hospital a few times to check on Billy Ray’s condition. (He did not tell Copeland that he had also visited the hospital with Wes and had made inquiries about Billy Ray at the front desk.) Their meeting ended with the investigator’s asking Corey to write a full report detailing what had occurred. Several hours later, Copeland received a call. “I need to talk to you about what we discussed this morning,” Corey said, and asked if Copeland would come by his house.

Corey had heard from someone at the sheriff’s department that he had been fingered as Billy Ray’s assailant, and when Copeland arrived, he was quick to try to set the record straight. Waiting on the porch with him were Wes and Colt, who let him do the talking. Billy Ray had in fact been assaulted, Corey told Copeland, and it was his friend Colt—whom he pointed to—who had done it. As the investigator listened, Colt then narrated his version of events: how he had been sitting alone by the bonfire, waiting for his friends to return from town, when a black man had approached him on foot from out of nowhere. The man had been physically aggressive and had advanced toward him, demanding that he turn off the country music he was playing. Colt had repeatedly asked him to leave, and when the stranger moved toward him again, Colt had knocked him out with one punch. Frightened, he had single-handedly loaded the man into his pickup, driven him into the woods, and left him by the side of the road. When he was finally able to track down Corey and Wes, he showed them where he had left the man, Colt said, and his friends had notified the sheriff’s department after he had gone home.

Colt’s account started to unravel as soon as Linden police investigator David Martinez began to interview other people who had attended the party, particularly Lacy Dorgan. (After Colt gave his statement, the case was turned over to the police department, since the pasture where the crime had taken place was located within the city limits.) As a fuller picture emerged of what had happened that night, Martinez voiced the opinion that Linden might have a hate crime on its hands. That, an officer at the sheriff’s department told me bitterly, “was like striking a match to dry brush.” Police chief Alton McWaters called in the FBI to investigate possible hate crimes and civil rights violations. The Associated Press picked up the story, and TV news trucks from Shreveport began rolling into town. The following week the Texarkana Gazette ran the first of four damning editorials. (“We were vilified,” one resident recalled.) Linden residents who braved the media did little to burnish the town’s image when they tried to downplay the crime, talking about the “good boys” involved who had been remiss only in letting things get “out of hand” and who deserved “a slap on the wrist.” Wilford Penny told the Chicago Tribune one month after stepping down as Linden’s mayor that the incident had been “an unfortunate and senseless thing” but that “the black boy was somewhere he shouldn’t have been.”

Billy Ray had regained consciousness on Wednesday, but the trauma to his head had resulted in permanent brain damage. (Having retained no memory of what had happened to him, he was unable to help investigators.) There was little dignity in his condition; he drooled and soiled himself, and his speech was severely impaired. When he tried to talk, his lips and tongue would not cooperate, and to all but a few family members who grew accustomed to the way he grunted his words, he was unintelligible. He had difficulty swallowing food and walking unassisted, and he often sat in his hospital bed and cried in frustration. After a month, when he still could not feed or dress himself, he was transferred to a nursing home in nearby Texarkana, where he gradually learned to walk again and recovered control of his bodily functions.

And yet, after Corey, Wes, Colt, and Dallas were each arrested and charged that October with aggravated assault (Lacy, who cooperated with investigators, was not charged), they were seen, by some, to be victims as well. “These boys’ names are ruined for life,” Corey’s mother, Martha Howell, later told one reporter. “And [Billy Ray] is better off today than he’s ever been in his life. He roamed the streets, the family never knew where he was. Now in the nursing home he’s got someone to take care of him.”

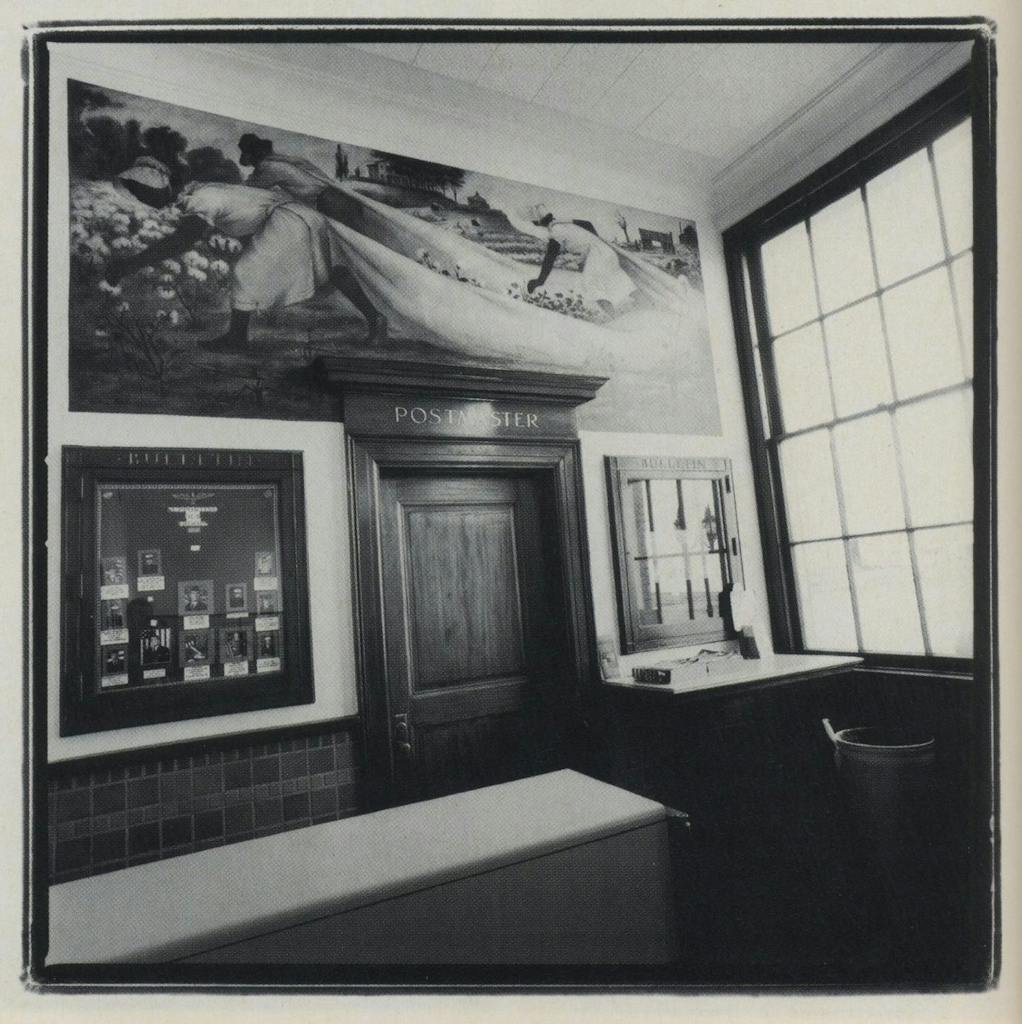

Sympathy for the four young men only deepened tensions. “She talked as if her son had done us a favor,” observed Lue. And the casual attitude about the harm done to Billy Ray was not limited to one defendant’s mother; among most whites, the crime seemed to provoke little outrage. “When this happened, the white community was quiet,” said the Reverend David Keener, of the Pleasant Hill Missionary Baptist Church, where blacks have worshipped since 1843. “No one stepped forward and said, ‘This is wrong.’ What had happened was awful enough, but the silence was worse.” To blacks, who make up 20 percent of the town, the indifference was only the latest symptom of what many considered to be an Old South mind-set that permeated life in Linden, most plainly in a mural that had hung in the town’s post office since the late thirties called The Cotton Pickers, in which three dark-skinned, barefooted sharecroppers are depicted toiling in the fields. The image and its prominence in one of Linden’s most public buildings were telling, some said, since neither native sons Scott Joplin, the ragtime composer, nor T-Bone Walker, who introduced the electric guitar to the blues, had ever been memorialized. “Generations of blacks saw that mural every time they sent a letter or bought a stamp,” Benjamin Dennis, the president of the Greater Texarkana NAACP, told me. “And the message they took away from it was that they shouldn’t aspire to be anything greater than a cotton picker.”

But the criticism from outsiders struck a nerve. Residents did not want to endure more scrutiny or hear assessments of their town’s flawed race relations. Most of all, they worried that any stain on its reputation could scuttle chances of economic renewal. Linden, which lacks even a stoplight, is bleak. U.S. 59, which used to be the main thoroughfare through town, was rerouted around Linden in the fifties, and two decades later, a Wal-Mart opened in the nearby town of Atlanta. Now the courthouse square is deserted, even in the middle of the day, and handwritten signs that read “Closed due to illness” and “Back later” hang indefinitely in empty store windows. People must commute to find steady work, and so they punch the clock at the paper mill in Domino, the steel mill outside Lone Star, and the Army depot west of Texarkana. Civic leaders had hoped to bring in visitors by showcasing Linden’s rich musical heritage, using the Music City Texas Theater, a restored American Legion hall that had proved successful in booking big-name acts, as an anchor. (The Eagles’ Don Henley, who has played sold-out shows at the theater, also grew up in Linden.) But the bad publicity threatened all that, and many locals hoped that if they ignored what had happened, it would simply disappear.

When I visited Linden last fall, few white people would agree to speak to me about the case. Those who did were wary of being quoted, and few of them showed much sympathy for Billy Ray. Anger still ran deep, and not at the defendants; it was Billy Ray, somehow, who had brought this upon Linden. People told me he was “a street person,” “a drunk who wandered the streets,” “a homeless guy who danced for money,” “a known crackhead.” Never mentioned was the defendants’ own prodigious alcohol consumption. By his own admission, Dallas had drunk ten beers before arriving at the pasture party, and he knocked back eight or nine more once he was there. But he and his friends were “typical teenagers,” residents told me, and “good kids.” Billy Ray was not even mentally disabled, I was informed by the executive director of Linden’s Economic Development Organization, Russell Wright. “He cooked his brain on drugs,” he explained. To see things any other way was to see Linden in a very ugly light.

NOT UNTIL MARCH 2005, a year and a half after the arrests, did the first defendant go to trial, and from the start of the State of Texas v. Christopher Colt Amox, it was apparent that justice might be hard to come by. Cass County district attorney Randal Lee had his assistant district attorney, Tina Richardson—a black woman who was the county’s only other prosecutor—try the case. But during the five-day proceeding, Lee did not assist her or take part in the state’s prosecution. “I drove fifty-five miles each morning to attend the trial, and I never saw the district attorney walk across the hall,” said the NAACP’s Dennis, who had previously attended a less-high-profile trial of a black defendant at which Lee had been present every day. “A DA who wants to bring the full judgment of his office down on an individual is going to make sure that jurors see him in the courtroom. It was obvious from the start that the full resources of the DA’s office had not been thrown behind this case.”

Colt, the defense’s only witness, took the stand and testified on his own behalf. “I want everybody to know the truth,” the clean-cut young man told the jury, which was made up of ten whites and two blacks. Colt’s attorney, Corky Stovall, began by guiding him through a show-and-tell of photos that pictured him smiling beside black teammates and acquaintances and then brought him to the crux of the message that he needed to impart to the jury: He had acted in self-defense. “He was coming toward me,” Colt testified, explaining that he had feared Billy Ray and had taken several steps away from him. “I mean, he could have hit me, stabbed me, shot me. I don’t know this man from anybody … Once he got to me, I felt like he was going to hit me, so I hit him, one hit in the mouth.” Colt denied ever using racial slurs, and he told the jury that he had made bad decisions—like driving Billy Ray into the woods and then washing out the bed of his pickup afterward—because Corey had pressured him to do so. Even the false accounts he had given to investigators had a noble justification. “I was trying to keep my friends out of trouble,” he told jurors.

In her cross-examination, Richardson pressed Colt to explain how the well-built former athlete could have felt physically intimidated by a man whom she estimated to weigh just over one hundred pounds—and who, unlike Colt, had had no friends with him to back him up. “Even a small person can shoot somebody or stab somebody,” Colt replied.

But Richardson overlooked one of the most powerful pieces of evidence that the state had to discredit his defense, which the FBI had turned up during its investigation: The morning after the assault, when Dallas had showed up for work at the Dairy Queen, he had confided in a friend that Colt and Corey were planning on making up a story to tell police that cast Billy Ray as the aggressor. Dallas, who had turned state’s witness, was not questioned about this at trial. He only testified that he had not seen Billy Ray behave aggressively toward Colt and that the assault had been unprovoked.

After several hours of deliberation, jurors acquitted Colt on both felonies—aggravated assault with bodily injury and injury to a disabled person by omission—which had each carried the possibility of a ten-year prison sentence. In doing so, they rejected the idea that Colt had targeted Billy Ray because of his race. They settled instead on a lighter charge, misdemeanor assault. The jury also recommended a suspended sentence: in other words, no jail time. Billy Ray’s family wept as the verdict was read.

A similar scene played out when Corey was tried two months later. There were plenty of unflattering facts entered into the record; Wes, who had also turned state’s witness, testified that Corey had said of Billy Ray, “Someone needs to whip the shit out of him.” But the jury was disinclined to convict him of assault when he had not thrown the actual punch. Corey was found guilty of injury to a disabled person by omission, or essentially failing to render aid. The jury was split along racial lines over the proper punishment, with its one black juror a holdout for jail time. But in the end, once again, the jury recommended a suspended sentence. When I met with the jury foreman, a warehouse manager named John Reed, he explained that some jurors had thought Billy Ray—who had taken the stand to give a few halting answers—had faked his symptoms and had practiced seeming slow and walking poorly. “As far as I’m concerned, everyone’s to blame,” Reed said. “Wes Owens shouldn’t have carried him out to that party, and Billy Ray should have known better than to go drink beer with a bunch of white boys.”

Judge Ralph K. Burgess, citing the graveness of the crimes, set aside the juries’ recommendations and gave each of the defendants short jail terms. Corey received a sixty-day sentence, to be served at the Cass County jail, which he had been summarily fired from during the investigation. The other three received thirty-day sentences. But the penalties were little consolation to people like Lue, who had fed and bathed Billy Ray between his stopovers at different nursing homes and who had seen firsthand how his cousin had suffered. “The verdicts sent a message: ‘It’s okay to treat a black man that way,’” Lue said when I visited him last fall. He showed me a small item he had clipped from the Cass County Sun, which he had glued to a piece of loose-leaf paper for safekeeping, about a black man named Burks Mack, who had illegally dumped some tires near Old Dump Road. For his crime, Mack had received six months in the county jail. “The only way I can figure it, a bunch of old tires is worth more than Billy Ray,” he said.

Lue echoed the sentiments of many blacks in Linden when he told me that the outcome would have been different had the races of those involved been reversed. “I didn’t go to law school, and I’m not a well-educated man,” said the Vietnam veteran and retired steelworker. “But I know enough to know that something ain’t right. If four black men had taken a mentally retarded white man to a party, made a monkey out of him, called him racial slurs, assaulted him, dumped him by the side of the road, and lied to the police about it, you can bet they would’ve gone to the penitentiary for a long, long time.”

THE CIVIL SUIT, which the Southern Poverty Law Center has filed on Billy Ray’s behalf, is slated to go to trial on April 2. Based in Montgomery, Alabama, the nonprofit group takes on high-profile civil rights cases, as it did most famously in 1987, when lawyer Morris Dees won a $7 million verdict that bankrupted the United Klans of America after two of its members in Mobile lynched a young black man named Michael Donald. Billy Ray’s suit, which names the four defendants, is seeking unspecified damages to cover the cost of speech and physical therapy as well as long-term care. “This justice system totally failed Billy Ray and his family,” Dees told me. “We want to give a jury the chance to correct an injustice in their community by presenting all the facts, many of which were not available to the juries in the criminal cases.” When I asked if he was worried about the odds of finding twelve impartial people to impanel, Dees claimed to be unconcerned. “These jurors grew up in a Christian community, and they know what’s right from wrong,” he said. “We have to present the case so they can see that Billy Ray is a human being who deserves to be treated just like anyone else.”

Just as hard as winning a settlement may be extracting any money from the defendants, who have spent the past three years working menial jobs while their friends have gone on to college. Wes intermittently works construction in Alaska; Colt is a truck dispatcher in Mount Pleasant; Dallas works for a heating and air company in Little Rock, Arkansas; and Corey is employed at a company that finds jobs for felons and minorities. They have all left Linden.

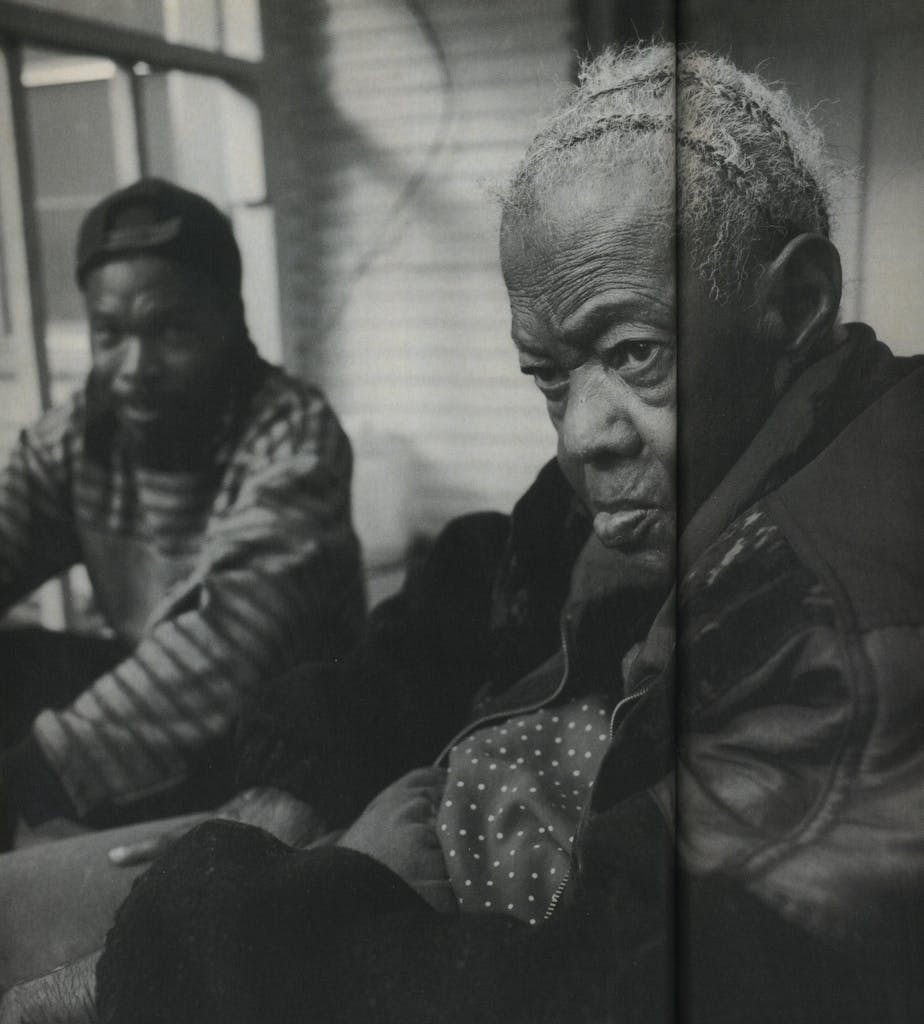

Billy Ray currently lives in a nursing home in Texarkana, where I went with Lue to visit him one afternoon last fall. Bouquets of plastic flowers brightened what was otherwise a dreary place. Just beyond the entryway, an Alzheimer’s patient wheeled himself down the hall, which smelled of bleach and urine. An obese man in a nursing gown sat next to a beat-up piano, chewing his lower lip and watching Gunsmoke. We went to Billy Ray’s room, where a small window afforded a glimpse of the sidewalk outside; his roommate dozed while a TV droned in the background. Billy Ray broke into a grin when he saw Lue, and he nodded at me, wordlessly sticking his hand out in greeting. He was even thinner than in the photos I had seen of him. His T-shirt hung loosely from his delicate frame, and his gray sweatpants were secured at his waist with a belt. He wore his hair in braids, and each time he smiled, he revealed a few wildly uneven teeth. Along the side of his shoes’ thick white rubber soles his name was written in indelible black ink.

Billy Ray sat quietly with his hands clasped in front of him while Lue asked him a few questions. He had trouble making even simple conversation, and when he did, his words came out as strange, mangled sounds that Lue often had to decipher for me. Still, he was eager to communicate; he showed us his collection of audiotapes, which he kept in a plastic bag, handing over each cassette for us to look at. Afterward he took us on a tour, and he proved to be popular with the nurses. “How you doing, Billy Ray?” said each woman who strode by, and he returned the attention with a shy smile. He did not need a wheelchair any longer, but he still walked stiffly, with his shoulders hunched over, moving like a man nearly twice his age. When we passed a woman with snow-white hair, Billy Ray pointed at her and said, “We friends.” We followed him outside into the courtyard, where he stopped and stood in the sunlight for a moment and closed his eyes, taking in the warmth of the late fall afternoon.

When we went back inside, we sat down in the lounge to talk. Lue said that it would be all right to ask Billy Ray about the assault, but as soon as I broached the subject, he began folding and refolding the white jacket in his lap.

“Do you remember anything about that night?” I asked him.

“Bonfire,” he said, nodding.

“Do you remember anything else?”

He thought for a long time. “Country Store,” he said.

“Do you know how you were hurt?”

“No, ma’am.”

“What do you think about what happened?”

Billy Ray furrowed his brow, and Lue and I had to lean forward to hear what he said next. “Wasn’t right,” he said, shaking his head. “Wasn’t right.”