This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Barry Sullivan knew he wouldn’t have the numbers yet; after all, as he put it, “image dimension changes precede the predisposition to buy by nine months,” and he had just started his radio campaign a few months earlier. So what he was really looking for at Willie Nelson’s second Fourth of July picnic was some subjective clue that his instincts, developed over twenty years of selling beer, were still steering him in the right direction. And on the evening of July 5, 1974, he got it. There he was, a vice president at the Lone Star Brewing Company, a good corporate soldier pushing fifty, watching Michael Murphey up on the stage in his white cosmic cowboy outfit and surrounded by 25,000 screaming country rockers of prime beer-drinking age. When Murphey got to the part about “Lone Star sippin’ and skinny-dippin’ and steel guitars,” the crowd let out a roar at the brief litany of homemade pleasures, and in that instant Barry Sullivan sensed that his beer was on its way to becoming part of a greater cultural vision. He had targeted his market dead on center. The numbers would definitely come.

This is a story of beer, brains, and the stuff that modern myths are made of. How Barry Sullivan and a handful of men like him turned a down-home Hill Country brew into the alcoholic archetype of Texas chic is not simply a story of marketing and advertising expertise. For Barry Sullivan and the men who preceded and followed him, that cold Lone Star was more than just a product. Like Greek vase painters, who reflected the changes in their civilization by subtly varying the stock Homeric legends over the centuries, those modern image makers approached that bottle of beer as a means of expressing their version of a changing Texas. What they have left us is a collection of artifacts, modern votive objects that archeologists could study millennia from now in hopes of understanding something fundamental about us. And if those future students of our times ever do unearth a longneck from the detritus of modern Texas, and if they’re very diligent in their research, the story they will tell should go something like this:

Selling the Big Country

In the beginning was Harry Jersig, now a retired San Antonio businessman, barrel-chested, broad-shouldered, and still in possession of a full head of thick, curly hair at age 79. Jersig was born in 1902 in Comfort, about fifty miles northwest of San Antonio. His father was the well-to-do son of German immigrants. After graduating from the University of Texas, Harry became an enterprising candy salesman who paid a Hill Country youngster named Lyndon B. Johnson 25 cents a day to tag along with him and open the ranch gates. Jersig prospered even after his employee left for other pursuits, and by 1940 he was enough of a success to be invited to buy into San Antonio’s sputtering, twice-defunct Lone Star brewery, which had been founded in 1868. Jersig, who had a brother-in-law in the beer business, took a more ambitious approach to the proposition. He talked two established brewers into buying the entire operation, engineered a public stock offering, began building a brand-new plant, and kept only the name of the old brewing company.

Jersig became president and took full control of the financial reins in 1948, but by that time Lone Star was already Harry Jersig’s beer. Jersig wanted to build an image for his beer, and he felt that the best way to build his beer’s image was to become involved in the community. That was a commitment that Jersig assumed personally, and he ended up heading everything from the United Fund to the chamber of commerce and was honored for his civic accomplishments by everybody from the Catholic College Foundation to the Exchange Club. He was also one of the handful of San Antonians who helped start the San Antonio River authority, which has been so vital to the city’s development. Jersig wanted his brewery to be just as involved as he was, so he built a lake and picnic grounds next to the plant, throwing parties and running an aquacade to bring people in, and when the aquacade closed in 1957 he replaced it with a museum adjacent to the plant. Over the years Jersig sent traveling shows to little towns all over Texas, entertaining the citizens with teams of ponies, trained dogs, and chimpanzees.

Jersig’s business style, which was essentially that of the civic-minded small businessman on a huge scale, was matched by his recreational pursuits, which were essentially those of a good ol’ boy carried to epic dimensions. Jersig was a prodigious hunter and fisherman, a sportsman of such renown that he was written up in Sports Illustrated, and he filled the Buckhorn Hall of Horns next to the brewery with dozens of trophies that he bagged all over the world. At the same time he served on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, stocked the Guadalupe River with trout, almost single-handedly fought to establish Mustang Island State Park, and was named Texas conservationist of the year in 1966. Harry Jersig put a lot into Texas, and he expected to get a lot out of it.

It didn’t take long for Lone Star beer to become an institution in and around Harry Jersig’s community. The new Lone Star was in fact the nation’s fastest-growing brewery during the forties, and the contractor didn’t move his shack from Harry Jersig’s brewery for nineteen years. Jersig worked hard to turn out a quality product, and one of the main reasons that Lone Star did so well in Texas was that it was promoted as exactly what it was, a good homegrown brew for good, solid, homegrown working people.

From 1946 until 1973, Lone Star’s advertising was handled by adman Ward Wilcox, who ran the account first for the Conroy Advertising Agency in San Antonio and later for the Glenn Advertising Agency in Dallas. His advice was simple and faithfully followed: this must remain a Texas beer for people who don’t mind hard work and a little cow manure on their boots. Every campaign Wilcox did for Lone Star was robust, outdoorsy, and unmistakably Texan. He invented slogans like “Clear Across Texas,” “Pure Artesian Well Water,” “The Real Thing,” and “From the Big Country” and tied them to spacious Texas landscapes, sparkling springs or frothy Gulf breakers, and lots of ordinary Texans enjoying themselves in the abundance that nature had provided. There was a particular emphasis on hunting and fishing, and Lone Star even sponsored a classic syndicated television show, Jim Thomas and the Lone Star Sportsman. In a state that didn’t have any major professional sports until the Dallas Cowboys appeared in 1960, sports meant high school and college football, and hunting and fishing.

Jersig liked the campaigns that Ward Wilcox created because they expressed his background and interests and because they worked. In 1965 Lone Star sold a million barrels (the 1980 figure is estimated at 750,000) and was even expanding into Oklahoma. But the Texas beer found that it had little appeal north of the Red River and received a drubbing from an aggressive Colorado-based brewing company, Coors. It was an ominous warning. By the late sixties the national brands were beginning to lick their chops over Sunbelt demographics, and anybody who could add could see the importance of Texas.

It took the national brands a few years to mobilize, but they descended on Texas in the early seventies and they hit Lone Star hard. Harry Jersig, despite the growth of his operation, still held many of the praiseworthy attitudes of a small businessman. The nationals could operate more economically because they could get their raw materials cheaper, but Jersig refused any suggestion of cost cutting that might compromise the quality of his beer. He began to think in his gloomier moments that a regional beer could no longer be competitive.

Generally speaking, Jersig was right; the outlook for regional beers nationwide was extraordinarily bleak. The regional brands still appealed to their loyal, usually older and more conservative consumers, but they were totally lost in the great demographic movement that was frantically hammering its stamp on every aspect of American politics, culture, and consumption habits. The postwar baby boom was coming of beer-drinking age, and the regional beers, with their old-fashioned images and in many cases old-fashioned executives, just hadn’t captured the baby-boomers’ imagination. The upshot was that regional beers were in the middle of a trend that would see their numbers diminish from about two hundred in 1969 to about fifty today. And by mid-1973, it was obvious that Lone Star, which wasn’t really losing many of its loyal drinkers but wasn’t picking up any of the new ones either, wasn’t bucking the trend.

Harry Jersig knew that he needed somebody new to handle his marketing when the incumbent executive frankly admitted that he didn’t know what to do. One of Jersig’s daughters was married to an officer of the Falstaff Brewing Corporation, and Jersig had heard about and briefly met a bright Falstaff marketing veteran named Barry Sullivan, who had let it be known that he might be interested in new venues for his trade. Jersig decided that Lone Star needed to get in touch with Sullivan.

Selling Woodstock

Barry Sullivan seemed to be Harry Jersig’s kind of man. He was a small-town Canadian, born and raised in Preston, Ontario. His real education came when he left the University of Toronto in 1945 to spend eight years as a big league hockey player, a journeyman right wing who thought the game was one of skill and finesse rather than naked aggression. But Sullivan was a huge man, as big as most NFL linemen of the time, and later in the world of three-piece suits people were always impressed by his size, his projection of athletic, outdoorsy vigor, and his ruddy, ruggedly handsome features. With an agile mind tied to a deep, gruff voice, Sullivan usually took command when he entered a room full of people, and everybody got the sense from his forceful, profanity-punctuated presentation that he would back up his ideas with action. Sullivan began to be known as a guy who might study a lot of statistics but who would ultimately act on his instincts. People who worked with him called him—admiringly—a hip-shooter.

Sullivan already knew a good bit about Texas, the beer business, and the beer business in Texas when he was approached by Lone Star. Sullivan had started full time with St. Louis-based Falstaff in 1953 (he had worked there in the off-season during his last three years as a hockey player), and for a time he was Falstaff’s man in Texas, which happened to be the company’s biggest state in sales. But the experience that really prepared Sullivan for his work at Lone Star began in 1968, when Falstaff assigned him to a sluggishly performing regional brewery that it had just acquired, the Narragansett Brewing Company in Cranston, Rhode Island.

Sullivan’s strategy for Narragansett came to him in the summer of 1969, when his two long-haired teenage sons drew his attention to an outdoor music festival near Woodstock, New York, that generated a great deal more interest than any of its promoters had expected. Barry Sullivan watched the news reports on TV and heard about it from his sons, and the whole thing impressed him very much. Here were all these nice young people, so well behaved that 300,000 of them could get together without incident. These were the kind of young people that any brewery would be proud to have as consumers and that a regional brewery like Narragansett had to have if it was going to survive. And as any fool could plainly see, the key to their hearts and minds was music.

Sullivan lost little time in launching a whole series of mini-Woodstocks in the cities, towns, and college communities where Narragansett was sold. No beer was actually sold at the concerts, and announcements of Narragansett’s sponsorship were kept within the nonhyperbolic limits that Sullivan felt the Woodstock generation required. The talent, however, included immortals like Janis Joplin, Led Zeppelin, Judy Collins, Santana, and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. Sullivan staged nineteen separate concerts, and he promoted each through the conventional channels of the youth movement: underground newspapers, FM rock radio stations, and 14-by-36 posters. The kids, among whom Narragansett had had a very negative image—it was even rumored to be Mafia connected—responded by changing their minds and starting to buy the stuff.

When Sullivan was transferred back to Falstaff’s main operation in St. Louis in 1972 to coordinate marketing for Falstaff’s operations nationwide, he found himself frustrated after his heady sense of freedom in Rhode Island. Falstaff, he realized, just wasn’t up to a direct assault on the youth market, which Sullivan believed was the crucial market to capture. So when he came to look at Lone Star in the fall of 1973, Sullivan saw the opportunity to prove his theories in the wider arena of the nation’s number two beer market. He examined the brewery operation itself and found it to be fastidiously maintained and up-to-date; Lone Star was obviously not suffering from any quality problems. He met with Lone Star president Eddie Sullivan on a Friday afternoon, and after that meeting went smoothly he was brought to Harry Jersig’s house on Saturday morning. In an hour and a half, he cut his deal with Jersig and was on his way home. He was to be named Lone Star’s vice president for marketing, with control of all sales, advertising, and marketing research. Interestingly enough, he was not questioned on his ideas about marketing strategy by Jersig or anyone else at Lone Star, and he saw no reason to reveal his plan: a direct assault on the youth market.

Sullivan spent his first two months at Lone Star just going over reams of marketing statistics. The patterns that emerged pointed up some obvious problems. In the first place, the only young people who were buying Lone Star were members of one exclusive group—white, redneck males, particularly those living south of Waco. Lone Star was indeed respected by its drinkers as an authentic, down-to-earth, and appropriately macho product, but that wasn’t doing much good in a state that was rapidly becoming more and more urbanized and socially liberalized. Second, Lone Star suffered from poor pricing policies. Its cans were priced too close to its returnable bottles, which meant that its returnables—usually a big money-maker for regionals—were not selling. So there were two immediate problems to be solved: attracting blacks, Mexican Americans, women, and, most important, young, well-educated, relatively liberal white males, and finding some way of making those skinny returnable bottles with the curiously elongated necks—longnecks, as they were known around the brewery—more appealing to the consumer.

In mapping his strategy, Sullivan had initially to consider the fundamentals of beer marketing, which involve who drinks beer and why he drinks it. Beer is essentially a young man’s product and a heavy user’s product; two thirds of all beer is consumed by men aged 18 to 34 who drink about a case a week. Not surprisingly, that kind of consumption usually tapers off with age, and an 18-to-24-year-old subgroup is really the key to the beer market, while a man over 34 is considered about as important as a running back of the same age would be to a football team’s rebuilding plans.

While these young fellows are flaming through their gusto-grabbing years, they are naturally faced with the selection of a brand to absorb their prodigious consumption, and that process of discrimination is very curious indeed. Eighty per cent of all beer drinkers will tell marketing researchers that they select, and remain loyal to, their brand of beer because of its superior taste, while in actual taste tests 90 per cent of them will be unable to distinguish their beer from four or five competing brands. In other words, most beers taste about the same. The only thing that the average consumer can legitimately say about the taste of his beer is that it tastes good because it’s his beer. And how does he decide what is his beer? Stepping into the consumer’s shoes to answer that question, most beer marketers get positively misty-eyed.

“The beer that a person drinks is a very emotional thing,” says Barry Sullivan in his version of the classic response. “Beer is a very laid-back product. If your boss says, ‘Let’s go have a beer,’ you know it means something entirely different than if he says, ‘Let’s meet for drinks.’ It means a real expression of friendship instead of a formal occasion. So beer is associated with that kind of feeling. Beer is like a good friend that a guy holds up for the whole world to see.” Other beer men will say that that bottle or can of beer is a mirror that reflects the personality of the guy holding it, or that it is a mouthpiece for ineffable sentiments that the average drinker feels deeply but couldn’t even begin to articulate. No matter what the metaphor, one thing is clear: when a guy reaches for a six-pack, he wants 72 ounces of his own values and aspirations. He picks his beer because he likes what his beer says about him.

What Lone Star said about the guy who drank it was pretty obvious to Sullivan from the thrust of Lone Star’s advertising over the previous twenty years, and from the ongoing Big Country television campaign that he found when he returned to Texas in the fall of 1973. But by this time the reputation of the redneck had reached its nadir—this was still the era of Easy Rider, not The Dukes of Hazzard—and those good, simple folk had an image that was at times sinister. The classic redneck was often seen—particularly by Texas’ convulsively liberalizing young people, who were being swept by the nationwide revolt in mores a couple of years behind the two coasts—as a bullying thug who would squash a gentle music lover beneath his dung-encrusted boots for no other offense than simply wearing his hair a bit shaggy. “From the Big Country” was definitely not the way to win the youth market.

Selling Longnecks

The Big Country campaign was scheduled to run through the spring of 1974, but it occurred to Sullivan that he could ignore television for a while and saturate radio with a new campaign that would appeal to all those music-crazy young people who must be tuned in out there. This would at least give him one medium in which Lone Star could be the dominant force. If he was lucky, he might be able to give his radio campaign a big head start before any of the competition knew about it and, for that matter, before many people at Lone Star knew about it. And Sullivan could take his lead from the kids’ music, just as he had from Woodstock four years before. That left only one immediate problem, which was figuring out if there even was a music scene in Texas, not to mention what was going on in it.

Sullivan went to Dallas and Houston on his opening forays into his new territory, but nothing in the youth culture of Texas’ largest cities appealed to his marketing instincts. Then he decided to visit Austin, where Lone Star was being thrashed by Budweiser in the prized UT market, and meet with the district manager, a Lone Star lifer named Jerry Retzloff. Retzloff was a San Antonio native who had gone to work for the brewery in 1963 as a tax accountant. In 1965 Harry Jersig took his industrious employee aside, told him he was destined to go further in the company hierarchy, and urged him to finish his college degree. Retzloff took classes in the mornings and worked afternoons and evenings at the plant. He got his marketing degree in 1971, and in 1972 he joined the sales force.

Jerry Retzloff had two serious avocations. One of them was fishing; his father had run three charter boats out of Port Aransas, and Jerry had even crewed for some of Harry Jersig’s parties back in the mid-fifties. Jerry’s father also worked with radio and sound equipment, and in the fifties one of his clients was a black country club in San Antonio that periodically showcased some of the country’s hottest black musicians. So Jerry met future cult heroes like Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, B. B. King, and Bobby “Blue” Bland back before most white folks knew they existed, and he ended up developing a sophisticated ear. And after he was transferred to Austin in 1973, Retzloff’s ear began to tune in to groups like Asleep at the Wheel, ZZ Top, and Greezy Wheels—groups that mixed country-and-western influences with rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll in a way that traditional country audiences would have found downright communistic, if not worse. He’d also heard a veteran Nashville campaigner named Willie Nelson, who seemed to be a father figure to a whole new music scene centered in Austin.

Sullivan and Retzloff first attended a concert together in Houston, when they flew a company plane down to a benefit featuring Willie Nelson and other Austin musicians. It was clear that something was going on, and after a few more pilgrimages—Armadillo World Headquarters and Soap Creek Saloon in Austin—Sullivan found himself absolutely amazed and delighted. The kids were reacting to this stuff exactly the way the kids at Woodstock had responded to sixties rock four years earlier. The only thing that was different was the country inflection, which in fact provided a convenient focus for ardent regional loyalties and in no way diminished the general youth-culture thrust of the phenomenon. This was Woodstock in Western wear. This was their music, and now all Sullivan had to do was make sure that Lone Star became their beer.

That, of course, would require some subtlety in execution, because if there was one thing that Sullivan had learned in Rhode Island, it was that the kids didn’t like hype. So he and Retzloff embarked on a grass-roots, almost underground campaign to get Lone Star noticed without appearing to be disagreeably capitalistic. One of the first things they did was make sure that all of the groups playing at Armadillo World Headquarters and the other country-rocker night spots got a free supply of Lone Star; drinking beer onstage was a ritual with many of the new scene’s culture heroes, and while Texas beers were in vogue, previously the beer was as likely to have been Pearl as Lone Star. And when Sullivan started casting around for a radio message, he knew that the kids wouldn’t buy another jingle; he needed a song. First he went to the company’s advertising firm, which was now called Glenn, Bozell & Jacobs due to a recent buy-out by the national firm of Bozell & Jacobs, but all he got out of it was another jingle. So he got together with Eddie Wilson, the Armadillo World Headquarters impresario, and told him he wanted a tune, not a jingle, preferably by one of the leading forces in the new Austin movement. Wilson’s first choice was the notorious Jerry Jeff Walker, but he turned out to be already on the Pearl payroll, so instead Lone Star got a tune by Walker’s sidemen, a group generally referred to as Gary P. Nunn and the Lost Gonzo Band. The song was a one-minute number called “Harina Tortilla,” a tune that mentioned Lone Star several times but beer not at all.

By the spring of 1974 the Big Country was still playing on television, but Sullivan was already dominating radio with a one-minute song performed by the Lost Gonzos, Freddie King, the Pointer Sisters, and Sunny and the Sunliners. He wasn’t even using an agency to produce the spots, relying on an Austin music consulting firm until they had a falling-out and Lone Star took over production. The bands would just come into the studio, read the lyrics, come up with some music, and receive the same fee that they would have gotten for a club appearance. Before long Sullivan was running six or seven hundred radio spots a week all across Texas.

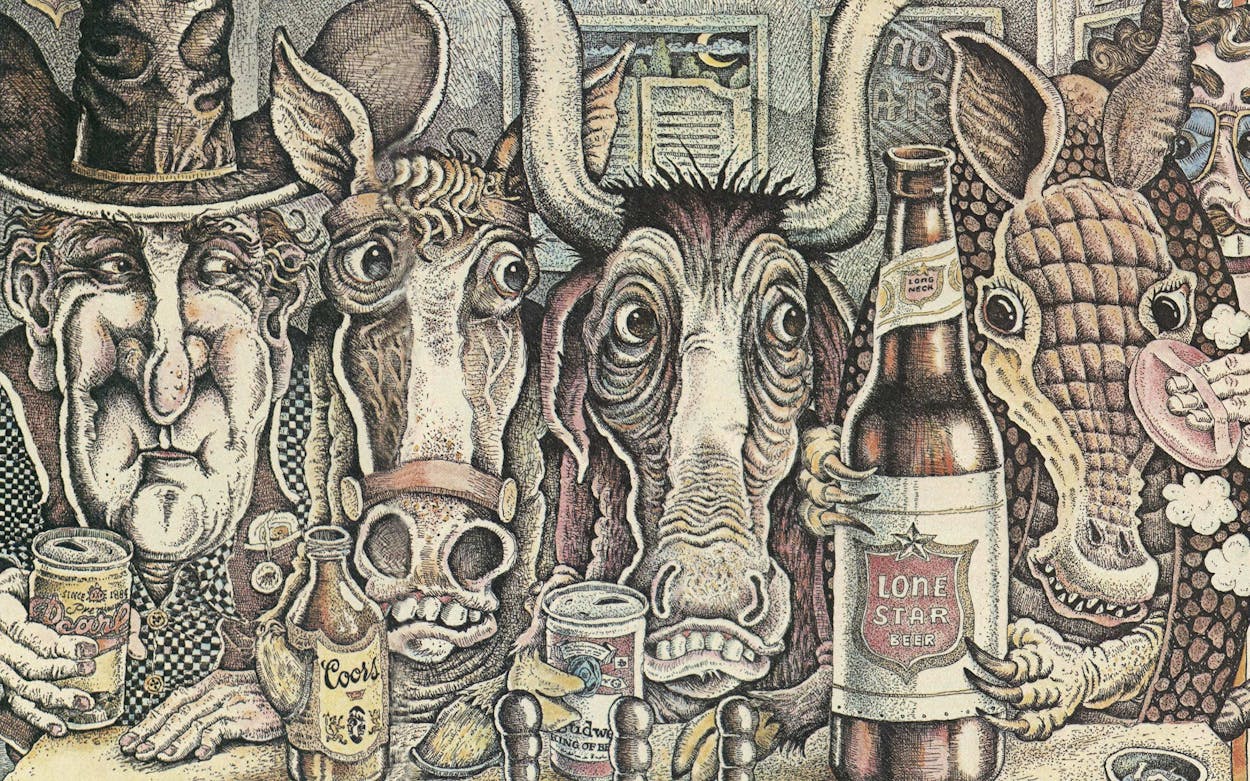

Sullivan supported his nascent radio campaign with an array of youth-culture gimmicks. Posters, of course, were essential, but when he got a couple of designs from a pair of Houston artists, he found them too slick, too much like advertising. So he went back over to Armadillo World Headquarters and had a creative conference in the parking lot with Jim Franklin, the resident eccentric as well as quasi-official staff artist. Franklin’s surrealistic treatments of the lowly armadillo had already generated a cult following and appeared on several album covers. Sullivan told Franklin to do anything he wanted, as long as it represented his vision of Texas and included a bottle of Lone Star, and he would essentially rent the image for a year, with the rights reverting to Franklin after that period was up. Franklin warned Sullivan that he was going to have to use some armadillos in his picture, and a few weeks later he came back with a provocative composition that to Sullivan resembled a landscape where “an atomic bomb had gone off and everything was laid waste and the only things that were left were longnecks sticking out of the ground and armadillos running around.” Sullivan wasn’t sure what it meant, but he didn’t question the artist’s insight. “What the hell,” reasoned Sullivan. “He knows the youth market.” Franklin went on to produce a series of memorable posters for Lone Star, including the classic Schooner in a Bottle, which had an old wagon stuffed inside a giant Lone Star bottle just like a model ship.

There were also production runs of the Lone Star Dude, a Western hat with Lone Star emblems on the hatband and a “pulltab” crease, as well as the usual T-shirts and bumper stickers. But the real stroke of marketing genius involved an item that Lone Star had been making for years. It was that beer bottle with its ridiculous long, skinny neck. Technically called an export bottle in the beer industry, it was the oldest-style container in the business and seemed to be moving rapidly toward extinction. But as they went to concerts and hung out in clubs, Retzloff and Sullivan were surprised to hear that people outside the Lone Star brewery also referred to it as a longneck. In fact, the longneck had a certain down-home chic.

This started Barry Sullivan reflecting on just what was in a name. He considered the recent spate of “streakings” on college campuses, and it occurred to him that a few unremarkable incidents had become a nationwide craze simply because a clever reporter had invented the word “streaking” to describe them. The word—the single, catchy, descriptive term—had been the genesis of the fad. Sullivan knew what he had to do. In April 1974 he went to Harry Jersig and asked his permission to make some changes regarding the small red, white, and gold label stuck to the middle of the export bottle’s neck. Lone Star had already experimented tentatively with a label that replaced the words “Lone Star” with “Long Neck,” but Sullivan persuaded Jersig to put the longneck label on all the company’s returnables. In July of the same year Sullivan further enhanced the returnable’s image by holding the line on its price while cans throughout the industry were increased by 60 cents a case. The longneck was on its way back.

Selling Texas

Willie Nelson’s second Fourth of July picnic marked the first blush of a love affair that was to flourish between Lone Star, progressive country music, and a lot of people who couldn’t think of one without the other. Over the years the list of performers who recorded Lone Star radio spots expanded to include almost everybody who was anybody in progressive country, from Freddy Fender, Steve Fromholz, and David Allan Coe—“Hi. I’m David Allan Coe, and the first thing I did when I got to Texas was meet Willie Nelson and drink a cold Lone Star, and I liked ’em both”—to B. W. Stevenson, Rusty Wier, and even Kinky Friedman—“Remember, when you’re driving, don’t forget your car or a cold Lone Star.” Before too long, artists were approaching Lone Star for the privilege of recording one of those famous one-minute songs, and Lone Star began to develop a reputation for helping establish careers via its radio spots.

Lone Star also sponsored a series of Lone Star Cross Country Rock Specials—patterned after Sullivan’s mini-Woodstocks in Rhode Island—that toured the state and featured many of the biggest names in progressive country music. Another important product of the symbiotic relationship between the music and the beer was the public television music showcase Austin City Limits, of which Lone Star was one of the original underwriters. But perhaps the most effective musical advertisement, and certainly the leading testament to Lone Star’s status in the music community, was an artist who never recorded a single note for Lone Star or received a cent for any promotional work. That was Willie Nelson himself, who often as not could be observed clutching a longneck while at work and who even performed at Lone Star’s sales meeting in early 1976. Not only did Willie give Lone Star credibility within the music scene but he also gave the beer a certain status among his fellow Texas celebrities. Willie’s buddy Darrell Royal, for example, called Sullivan one day to order 120 black Lone Star T-shirts for his squad. “Damn,” gushed the coach, “you’ve improved the taste.”

Lone Star’s new cult status was finally quantified when the 1975 sales figures for longnecks came in. They showed a one-million-case increase in sales, highlighted by a 40 per cent jump in Austin. But while the image change that would produce such staggering numbers was going on, the folks back at the brewery were almost as blissfully unaware as residents of some tropical capital slumbering through a palace coup. Sullivan never played any of the commercials for Harry Jersig because he was understandably worried about lyrics that could be construed as referring to such things as brownies containing controlled substances. Members of Sullivan’s own staff were also a bit in the dark as to what was going on. The old-school Lone Star crowd just couldn’t see their beer as anything other than a product of that now vanished community of Texas, and that pointed up the problem Sullivan faced when he started thinking seriously about TV commercials in the fall of 1974.

What Barry Sullivan had already accomplished was as neat and surgical a “segmenting” of the market as you could possibly hope for with beer drinkers. In mounting his radio campaign he had brought an entirely new image of Lone Star before the youth market, but at the same time he had done nothing to alienate the hard-core Lone Star drinkers of yore, those staunchly loyal redneck he-men who wouldn’t be caught dead in tank tops and straw hats. The reason these loyal drinkers hadn’t been turned off was that they had never bothered to turn on any of the radio stations that were now serving up progressive country music. But television is the heavyweight medium in beer advertising, and by late 1974 Lone Star needed something to follow the Big Country. On television, there would be no way to have one campaign for the rednecks and another for the redneck rockers. On the barren wastes of America’s great cultural leveler, there was no place to hide.

The television campaign would also require the help of the company’s advertising agency, which was still Glenn, Bozell & Jacobs. But Ward Wilcox had died in 1973, and the agency’s president decided to bring in a grizzled veteran of California’s counterculture campaigns. Tom Monroe, a 30-year-old Iowan who was working in Bozell & Jacobs’s Los Angeles office, had never set foot in Texas until he moved to Dallas to assume his new duties, and he was the first to admit that he didn’t have any idea what Texas was all about. He hired Ron Fisher, a 29-year-old South Carolinian who had spent the last half of the sixties in San Francisco. Bozell & Jacobs’s reasoning was that Monroe and Fisher were young enough to figure out what was going on in a Texas where understanding change was probably going to be more important than understanding tradition.

Within weeks after arriving from Los Angeles in the summer of 1974, Monroe was wearing jeans and cowboy boots and hitting the Austin clubs with Sullivan, and before too much longer the Glenn, Bozell & Jacobs team was writing many of the lyrics for the radio tunes. But the television campaign, which was their primary responsibility, wouldn’t be as easy.

Barry Sullivan gave the admen some guidelines that from the outset broke most of the rules of television advertising. He wanted sixty-second spots instead of the usual thirty seconds, which he figured would be long enough to get in a nice musical number to back up the action. As far as the action went, he wanted something distinctly Texan and somewhat compatible with the tradition of Harry Jersig’s beer. But most emphatically, he didn’t want to see any storyboards, which are sort of movies in picture-book form in which every camera angle, actor’s movement, and line of dialogue is scrupulously detailed in advance. The main functions of the storyboards are to show the client exactly what he is getting and to make sure that he then gets it. But Sullivan didn’t want Harry Jersig to see any storyboards; he wanted to present what he hoped would be pleasantly innovative commercials for Jersig’s approval when they were already faits accomplis. So the challenge to the admen was summed up by the fact that they would ultimately have to please both Barry Sullivan and Harry Jersig.

The first thing the creative team had to worry about was not alienating the loyal old-school Lone Star drinkers; the second was not alienating the new, younger, more progressive Lone Star drinkers. As a third criterion, they had to consider the ferocious regional pride that they had soon identified in both recently arrived and native Texans. And finally and most important, they knew that they had to be noticed. Radio might be a fine place to woo an important segment of the market, but television, as Monroe put it, “is where you build image.”

Thinking it over, the creative team figured that a national brand seeking to capture the Texas market would portray rodeos, roundups, or other clichés of Texas culture. That, they thought, wouldn’t be good enough for Lone Star; as Monroe said, they needed “a more intimate involvement with the state.” What they wanted were “bizarre cultural rituals” that would seem as vivid and exotic to a non-Texan as a Lithuanian folk festival. The first thing they came up with was the relatively tame idea of a chili cookoff, but they rapidly progressed to such spectacles as the Cuero turkey trot, an armadillo beauty contest, a watermelon-seed-spitting contest (for distance), and a buffalo chip toss-off (for accuracy).

When production began, the Glenn, Bozell & Jacobs team took full advantage of the freedom allowed by Sullivan’s no-storyboards edict. A crew was dispatched to the site of the event and a casting call put out for local amateurs, who would then proceed to party, play, and clutch bottles and cans of Lone Star in front of the cameras with minimal directorial guidance.

The crews would return with about 10,000 feet of cinema verité that was then edited into a mere 72 feet of raucous good times. The real key to the editing, and the commercials, however, was that good ol’ sixty seconds of country music. The Glenn, Bozell & Jacobs team wrote lyrics—“Grab that longneck for a taste of Texas tea and limber up them lips for a watermelon seed”—that were performed by the likes of Dave Mason and Red Morgan; television required that the music be somewhat less progressive than the radio spots permitted. But what the admen ended up with was a spontaneous, good-humored, catholic, but distinctive view of Texas that just about anybody could enjoy. For the first time in a Lone Star ad, you could see blacks, women, Mexican Americans, and young people enjoying themselves along with more mature rustic types. And Harry Jersig gave his implied consent at the end of the first few commercials: “The gobbler gallop and Harry Jersig’s Lone Star beer,” the announcer would intone at the end of the song. “No place but Texas.”

Selling Out

The first of the new television ads ran in February 1975. The U.S. Brewers Association voted the Lone Star TV spots the best beer commercials of 1976—a distinct honor for a small regional campaign. The aesthetic success was matched by strong sales figures for the first half of 1976, the ongoing prestige of the radio advertising, and an apparently rosy outlook for 1977. Lone Star had seemingly done the impossible, which was to capture the imagination of the new Texas without losing the loyalty of the old. Within three years of Barry Sullivan’s arrival, Lone Star longnecks had become a Texas institution and a nationwide symbol for the Lone Star State, and 1977 looked like a year when Sullivan would be able to sit back, put up his feet, and enjoy his success. But by mid-1976, all he could see on the horizon was the awesome juggernaut of Coors.

The brewing business is as close to a game of chance as you can find in legitimate commerce, and fortunes can wax and wane with a suddenness that is at times inexplicable even to the most knowledgeable men in the field. The gambling nature of the business merely reinforces its mercurial ascents and descents, because distributors—the people who actually purvey beer to retail outlets—are just as eager to throw in with a hot hand as they are to abandon a sinking ship. And in mid-1976, Coors, which had become a cult beverage with college kids throughout the West, was as hot as they come. Coors was known as a profit generator, and when it offered a distributorship for Houston, two hundred people, from astronauts to doctors to athletes, applied for the honor, expense, and ultimate profit of bringing Coors to Texans. With all that competition among potential distributors, Coors could be sure that its distribution network would be well funded and extremely energetic. Coors entered the South Texas beer markets like the hordes of Genghis Khan charging across the grasslands of central Asia.

In addition to Houston, Coors had targeted Waco, Temple, Austin, and South Texas in general. Lone Star decided to fight its rival tooth and nail; the brewery assigned fifteen men to follow every Coors truck in Waco to make sure that Coors wasn’t stealing any of Lone Star’s space on the refrigerator shelves. Because of this spirited defense Lone Star was hurt less than any of the others, but it was hurt. Harry Jersig, already wary of the nationals’ power, didn’t like to see any loss of volume, and his pessimism returned.

Jersig’s anxiety led him to think more seriously about an offer from another one of beer’s instant high rollers. Washington-based Olympia had expanded dramatically across the northern tier of states by buying out Hamm’s at a fire-sale price, and the new assets had boosted Oly stock from $11 a share to $40. Suddenly rich—at least on paper—Olympia wanted to trade its beefed-up stock for Lone Star shares and take control of the operation. And Jersig, an aging gambler sensing the cooling of what might be his last red-hot streak, decided to get out while he was ahead—way ahead. The original $118,000 that bought Lone Star in 1940 was now worth $35 million. Invited to stay as a sort of advisory figurehead, Jersig told the Oly people that he didn’t want an office, a desk, or even a chair at the brewery. He retired to hunt, fish, supervise his fortune, and dote on his grandchildren, and he goes back to Lone Star only to visit.

Meanwhile, Barry Sullivan had some doubts about his new employers. To his mind Olympia had gained sales volume in its acquisition of Hamm’s, but not profitability. Hamm’s facilities were antiquated, and the modernization that they required to become productive would further reduce profits that were already not terribly substantial. Olympia was standing on a foundation of stock-exchange paper, and Barry Sullivan knew it. Worse still, Olympia’s executives seemed to have no awareness of the only market that could provide the bedrock of a great brewing edifice, the youth market. Oly’s “It’s the Water” slogan and vignettes of lumberjacks were reminiscent of Lone Star’s old image, but nobody at Oly thought a change was necessary. Sullivan was particularly struck by a remark from one of Oly’s men in Wyoming, which had just been invaded by Coors. “Gee,” said the Oly guy in wonderment, “Coors didn’t hurt us.”

“Yeah,” gruffed Sullivan, “because you never had the youth market to begin with.”

If Sullivan had doubts about the parent company, he was equally disturbed by its plans for Lone Star. Experiencing “a broadening communications gap” with the new management and tired of the beer business, he decided to accept an opportunity to go into business for himself late in 1977. Today he is part owner of a manufacturing firm in Winters, forty miles south of Abilene, that specializes in metal toolboxes for pickups. The era of longnecks and galloping turkeys was over, and the era of Cooter and the giant armadillo was about to begin.

An Olympia veteran named Bob Ross took over as Lone Star’s vice president for marketing and sales, and he and his sales manager, Bill Monroe, began to study the performance of Lone Star and consider new marketing directions. Like Sullivan, the new marketing team had access to a great deal of information about Lone Star’s sales performance, and in reviewing the data they could just as easily perceive that a distinct pattern had emerged during the Sullivan years. There was no doubt that Sullivan’s campaign had been stunningly successful; in fact, the real problem that confronted the new team was the very success of the previous regime’s promotional efforts. The figures showed that Lone Star had been well received by two distinct groups: the all-important 18-to-24-year-old male general audience and the 24-to-34-year-old male “native redneck” audience. These two groups, of course, corresponded to the youth market that Sullivan had acquired and the traditional Lone Star drinkers that he had hoped to retain in spite of the new redneck rock affiliation. So everything had actually worked as intended, and everything would have been just fine if only Texas could have become a demographic Brigadoon in which the inhabitants emerged only to purchase a six-pack or two. But Texas was changing.

The first big problem was that all of those cosmic cowboys were getting old, and as they passed beyond their halcyon beer-consuming years, their market importance was diminishing. They were also growing old in a state in which the major urban areas were burgeoning fantastically, and these important markets were becoming increasingly heterogeneous, with blacks, Mexican Americans, and particularly immigrants from other urban areas—all more likely to be consumers of major brands like Bud, Coors, or Miller—becoming serious factors. Even the college communities, where Lone Star had become so entrenched, were being swept by the winds of change, and the word that “the Greeks are back” was like a hurricane warning to any marketing pro.

The then current Lone Star image was, to the minds of the new marketing regime, out of sync with this new Texas. “The image it presented of Texas was too strong and too narrowly defined,” says Bill Monroe, who succeeded Ross as vice president for marketing and sales. “We found that the people we talked to considered themselves Texans and were proud to be Texans, but they couldn’t see themselves throwing buffalo chips.”

As Lone Star’s new marketing staff saw it, there were now more formidable forces at work than simple regional pride. Texas was still the number two beer-drinking state—trailing California—but it had the potential to become the significant marketplace of the eighties. Texas seemed to be on the verge of capturing the imagination of the American consumer just as effectively as the California good times and good vibrations ethos had in the sixties and early seventies. But it would be a more sober, more conservative, more patriotic America that would embrace the Texas lifestyle. Even before the Reagan landslide, a change-weary America, frustrated by failed utopias and a feeling of national impotence, was turning back to the old values. And right there in the middle, symbolizing all of the pride, industriousness, success, and belief in success that this battered country wanted to feel, was Texas. And Texas, and Lone Star, seemed to have the potential for saying what the average Joe felt but was maybe a little shy about articulating. “How do you say that I believe in the work ethic and I’m proud to be an American?” asks Bill Monroe. “There’s no way to say that except to have the appearance of being a Texan.”

Selling Cooler

This realization presented a rather interesting paradox. By 1980 it was far more important to be a Texan, or to have the appearance of being one, than it was in 1970, while in fact that Texan of 1980 was likely to be much less distinctly Texan than he was in 1970, and much more representative of America as a whole. So the new Texas consumer was prouder than ever before to be a Texan, but you had to express his pride in a way that recognized that he was actually much less like a Texan and much more of a mainstream American than ever before.

The Lone Star people felt that this new situation once again required new advertising blood, but this time they decided to turn to a new agency and let the long-standing relationship with Glenn, Bozell & Jacobs lapse. They looked for a Texas agency, but after failing to find one with “sufficient expertise in malt beverages,” they asked for a presentation from a small Los Angeles firm, keye/donna/pearlstein, that had already done some promotional work for Olympia. This time the Lone Star marketing team decided that television would be the dominant medium for the image change, while the radio spots, now under the virtually autonomous direction of Jerry Retzloff, would continue unchanged in order to nurture and protect the old franchise; the basic strategy of creating new markets without alienating old customers was the same as Sullivan’s, except the roles of television and radio were reversed. To ensure that the new TV commercials reached the new audience, the marketers requested that the prospective admen “explore nontraditional forms of beer advertising with respect to humor.” Most beer advertising presents the product as a sort of spoil of victory after a hard day of assaulting one’s professional obligations—“For all you do, this Bud’s for you”—but Lone Star wanted its consumers to loosen up and laugh a little. Texans, the company figured, had a particular affinity for humor and outrageousness.

In order to find out for themselves what was going on in Texas, the Los Angeles admen commissioned a number of marketing studies in Texas. These were basically “mall intercepts,” which involve quizzing scurrying shoppers on their subjective responses to various marketing and image concepts, and “focus groups,” which essentially do the same thing over a longer period of time with a paid, captive audience. The studies pointed to the same conclusions that the Lone Star marketing statistics revealed—the image of the beer was too narrowly defined—but also provided some initial audience response to new ideas for ad campaigns. One catchy phrase that rated high with the guinea pigs was “the national beer of Texas,” while another commercial scenario was so well received that it became the basis for a set of storyboards that would compose part of keye/donna/pearlstein’s first presentation to the Lone Star marketing staff.

The storyboards depicted a Last Chance Saloon located somewhere in the empty vastness of Texas, with a sign nearby warning, “Next Stop for Lone Star 40 Miles.” In the commercials cars would come to a screeching halt, and a number of comic scenarios with the same theme were envisioned, ranging from fugitives fleeing the police to aliens in flying saucers. Unfortunately, the proposed commercials also suggested that the parched trans-Texas travelers might be continuing their journeys in various states of inebriation, a link between driving and drinking that was considered too unsavory for a public-spirited brewery.

At the same time, other potential commercial characters were proliferating among the storyboards and sketches like unborn souls awaiting the moment of fate that could give them life. One of these strange beings was a cartoon horny toad named H. T., who frequently met an armadillo named Dill in a local bar for an after-work Lone Star. H. T. was something of a show-off and given to inventing Texas tall tales, while Dill was slow-witted and generally served as a comic foil for H. T. Everybody liked H. T. and Dill, but they were finally deemed too unsophisticated for the new Texas. The cartoons were junked along with the Last Chance Saloon idea, but Lone Star was nevertheless impressed and gave keye/ donna/pearlstein the account.

The next ill-fated series of proposals involved a spoof on the Miller Time campaign that would feature oil field workers hitting a Lone Star gusher, reminiscent of an earlier Jim Franklin poster, or shrimpers hauling in a net filled with a giant Lone Star bottle. With the deadline looming, the giantism and armadillo ideas were combined in a proposed print ad that was headlined GIANT ARMADILLO ATTACKS BEER TRUCK beneath an appropriate illustration. A series of storyboards began to develop around the theme of the giant armadillo attacking a beer truck and slurping up all of the Lone Star, and the sort of reaction this make-believe event would occasion among humorously stereotypical Texans. At last the admen felt they had a theme that the brewery would accept.

After four spots had been completed in storyboard form, the cameras started rolling. The first featured Kenny Davis, a stand-up comedian who plays in C&W clubs, as a harried driver who tried to convince a couple of state troopers that his truck had indeed been attacked by the monstrous animal. The key lines were Davis’s “You gotta believe me” and a trooper’s reference to “the national beer of Texas.” In the second commercial the giant armadillo satiated his lust for beer by attacking the Cadillac of a scoffer who failed to heed a police roadblock, while in the third the armadillo assaulted a bar, ignoring the pretzels but consuming all the Lone Star. In the fourth ad, a cowardly slacker named Cooter tried to avoid driving his beer truck down the giant armadillo-plagued highways.

The four completed commercials were presented to a meeting of the Lone Star distributors and sales force in April 1980; in the middle of the meeting a newsboy came in, shouting, “Extra, extra, giant armadillo attacks beer truck!” In May 1980 the spots started running. Months later, when the figures started coming in, the Lone Star marketing regime was claiming success. (However, Lone Star stopped publicly releasing its sales figures when it was acquired by Olympia.) And conceptually, the people at Lone Star felt that the ads were right on the beam. Here was a heavy dose of Texas chauvinism, but it was all passed off in the form of National Lampoon or Saturday Night Live irreverent humor, and you didn’t need to have any particular insider’s knowledge of Texas to enjoy it. The most recent commercial, for example, redid the closing scene from Casablanca, with a beer truck driver named Billy Don reliving the Bogey role as he prepared to embark on his armadillo-threatened run; the scene relies on the viewer’s ability to relate to all-American nostalgia and slapstick Texas characterizations. This was Texas for an American audience.

Meanwhile, the nationals have reacted like mighty armies adopting the tactics of guerrilla forces that have bushwhacked them time and again. Anyone who has been close to the tube in the last year or so is familiar with such lines as “The Florida Keys and Milwaukee are a whole country apart, but to these guys they both mean the same thing” or “Michelob brings you the seven-day weekend, Southern style.” The nationals want in on the regional mystique, and with their massive advertising budgets and distribution networks, they are unlikely to be denied.

Today Lone Star has to contend with raids on its most sacred promotional territory. Coors is bringing out a longneck to try to grab the C&W crowd, and other major brands have whittled away at Lone Star’s musical stable. Former Lone Star commercial performer Charlie Daniels has now been signed by Budweiser, and Miller even had the audacity to go after Willie Nelson, who couldn’t be bought. Right now Lone Star is clinging to what it calls its “nonpreemptable brand position,” which means that as long as it is around, no other beer can claim to be the national beer of Texas. And to continue that assertion, Lone Star plans to keep up the giant armadillo campaign that introduced it, hoping to retain viewer interest with a continuing melodrama based on Cooter, the cowardly beer truck driver.

Insiders claim that Lone Star is hurting just as badly as its parent company, which, as Barry Sullivan had feared, never did turn the corner on profits and has seen its paper fortune drop from $40 a share back to $13. Lone Star executives, admitting that the nationals “have funneled all of their resources against us,” sound like football coaches preparing for a loss by emphasizing the overpowering strength of the opposition. But Lone Star has come back from the brink before, and for now the story has an open ending. Will Cooter and the giant armadillo save the brand, or will Lone Star have to come up with yet another image? Do Texans even care enough about having a national beer for Lone Star to survive? Who knows? If we knew the answer to those questions, then we could probably say that we know our own future as well.

Changes in Pitch

Three different ways of selling the same beer.

Big Country Image

In the early days, Lone Star was presented on television as the beer of the wide-open spaces. Ads emphasized the pleasures of “the Big Country,” of hunting and fishing. The campaign had plenty of appeal for people who had always been Lone Star drinkers, but it left the younger generation unmoved.

Cosmic Cowboy Image

The progressive country music scene in Texas, and especially in Austin, gave Lone Star what it wanted next—a trend to hitch its advertising wagon to. Commercials featured events like a buffalo-chip-throwing contest in which musicians like Rusty Wier appeared for Lone Star. The ads helped along several music careers in addition to the beer.

National Beer of Texas Image

The armadillo turns. The victim of the highways becomes the terror of Lone Star beer truck drivers in the most recent series of commercials. The idea of a giant armadillo going around slaking its thirst for Lone Star was a humorous angle the brewery’s Los Angeles ad agency thought would appeal to a new generation of Texans in the eighties.

Gone and, Quite Frankly, Forgotten

There were those who loved these vanished Texas beers, but that was a long time ago.

Texas beer has been around almost as long as Texas has. In the early 1850s an Austrian immigrant built the Kreische Brewery, the state’s first, near La Grange. Others, including Pearl in San Antonio (1886) and Spoetzl in Shiner (1914), followed. Then came Prohibition, which killed all the legitimate liquor business (Pearl and Spoetzl survived by operating as icehouses), and not until after Repeal did the industry start hopping again. The actual number of breweries in the state never varied much—there were always about six, the same number as today—but managements changed hands constantly and brands came and went with the seasons. By the mid-fifties the national breweries had expanded into Texas and few regional labels remained. Here’s a sampling of defunct Texas brews that were loved in their day but are now well-nigh forgotten by everyone except beer bottle collectors and drinkers with long memories.

Grand Prize

Appeared in 1935 and five years later was the best-selling beer in Texas. The company that made it, Gulf Brewing of Houston, was owned by none other than billionaire Howard Hughes, who built the brewery in the same complex as Hughes Tool. Hamm’s bought Gulf Brewing in 1953.

Bluebonnet

One of the first beers to capitalize on Texas chauvinism by using a state symbol. Maybe that’s why it’s better remembered than other area labels like Famous Black Dallas and Schepps. Dallas–Fort Worth Brewing took over the Time beer plant in 1940 and produced Bluebonnet until the early fifties.

Southern Select

Produced in the old Magnolia Brewing plant in Galveston in the forties and fifties. The company, renamed Galveston-Houston Breweries, eventually was sold to Falstaff, and the label was abandoned. In 1980, though, Pearl picked up on the name and began brewing a new Southern Select from its own recipe.

Marques

A beer ahead of its time. Lone Star introduced this dark European-style beer in 1965, touting it as a palate-pleasing gourmet beverage—“The Continental Beer”—rather than a slug-it-down brew. The Texas market wasn’t ready for it, though, and production lasted only a couple of years.

Mitchell’s

Named for Harry Mitchell, a drinking Texan who, undaunted by Prohibition, ran the Mint Cafe in Juárez in the twenties. After Repeal, Mitchell set up shop in El Paso and brewed his own beer till 1951, when he turned the business over to a group of private investors, who later sold their interest to Falstaff.

JR

A fad that fizzled. Produced by Pearl, JR first appeared in October 1980 and took its name from J. R. Ewing, the villainous protagonist of the television show Dallas. Production lasted a mere six months, and demand was always stronger overseas than on the Ewings’ home turf. Anne Dingus

- More About:

- Libations

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Beer

- San Antonio

- Austin