There are two kinds of gamblers: those who bet on games of chance and those who bet on games of skill. The best Texas gamblers without exception belong in the second category. There are bad roulette players and craps shooters—people, who don’t know the percentages and don’t know how to handle money—but there are no good ones, simply because the odds against the player are inexorable.

A Dallas gambler says there is only one way to approach playing the tables. “Decide in advance how much you’re willing to lose,” he says, “and if that’s all you lose, consider that you’ve broken even. Any losings less than that, consider winnings. Any profits, consider luck. If you want to make money gambling, stick to games of skill.”

Ah, but that’s the catch: first you’ve got to have the skill. Thousands of dollars change hands every year simply because their former owners failed to appreciate that just because a game is played with dice or cards doesn’t mean it is mostly luck. Craps, yes. Backgammon, no. The difference lies in the presence of absence, of house odds and the ability or inability of a player to affect the course of play through strategy. Never make the mistake of thinking that a game of skill is anything less. For the average player, a game of skill against a knowledgeable adversary is far more dangerous than a trip to Las Vegas. At least in the casino you only concede the house an edge of 5 per cent. The average player spots an expert at least 20 per cent in a game like backgammon; in bridge or poker he has virtually no chance.

The people on the following pages—T. A. Preston, Jr., of Amarillo, the Oswald Jacoby family of Dallas, and Bobby Nail and Ed Wilson of Houston—share a love for action, a head for figures, and an uncanny ability to ignore the fact that they’re playing for more than they can afford to lose. But as any professional will tell you, he can afford to win at any stakes. — Paul Burka

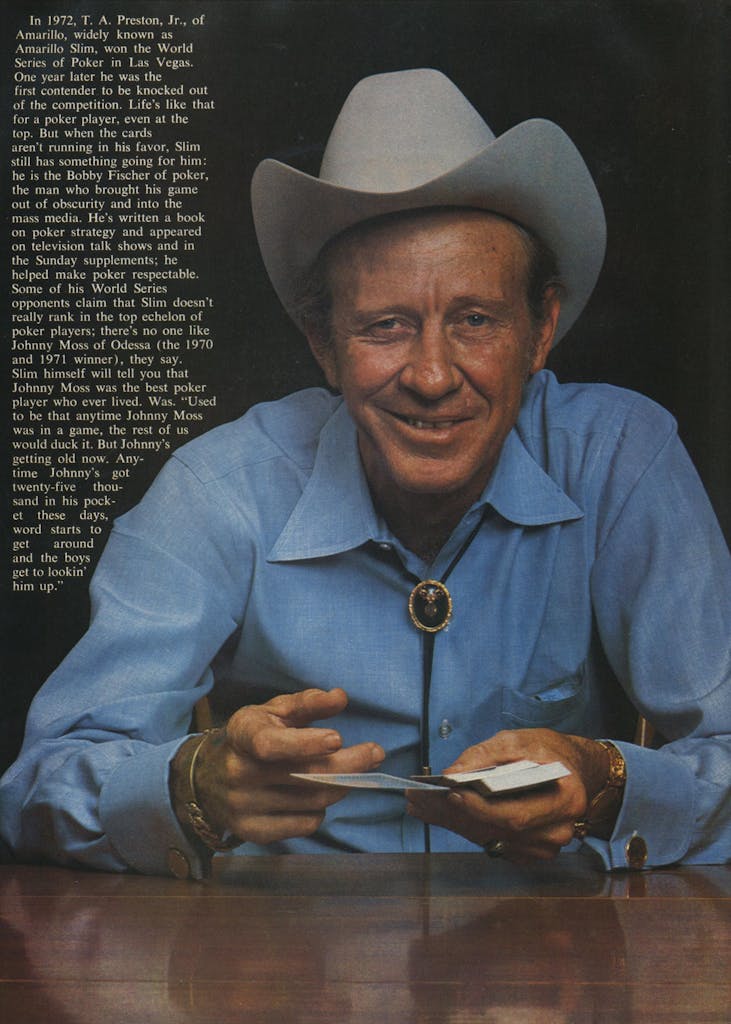

In 1972, T. A. Preston, Jr., of Amarillo, widely known as Amarillo Slim, won the World Series of Poker in Las Vegas. One year later he was the first contender to be knocked out of the competition. Life’s like that for a poker player, even at the top. But when the cards aren’t running in his favor, Slim still has something going for him: he is the Bobby Fischer of poker, the man who brought his game out of obscurity and into the mass media. He’s written a book on poker strategy and appeared on television talk shows and in the Sunday supplements; he helped make poker respectable. Some of his World Series opponents claim that Slim doesn’t really rank in the top echelon of poker players; there’s no one like Johnny Moss of Odessa (the 1970 and 1971 winner), they say.

Slim himself will tell you that Johnny Moss was the best poker player who ever lived. Was. “Used to be that anytime Johnny Moss was in a game, the rest of us would duck it. But Johnny’s getting old now. Anytime Johnny’s got twenty-five thousand in his pocket these days, word starts to get around and the boys get to lookin’ him up.”

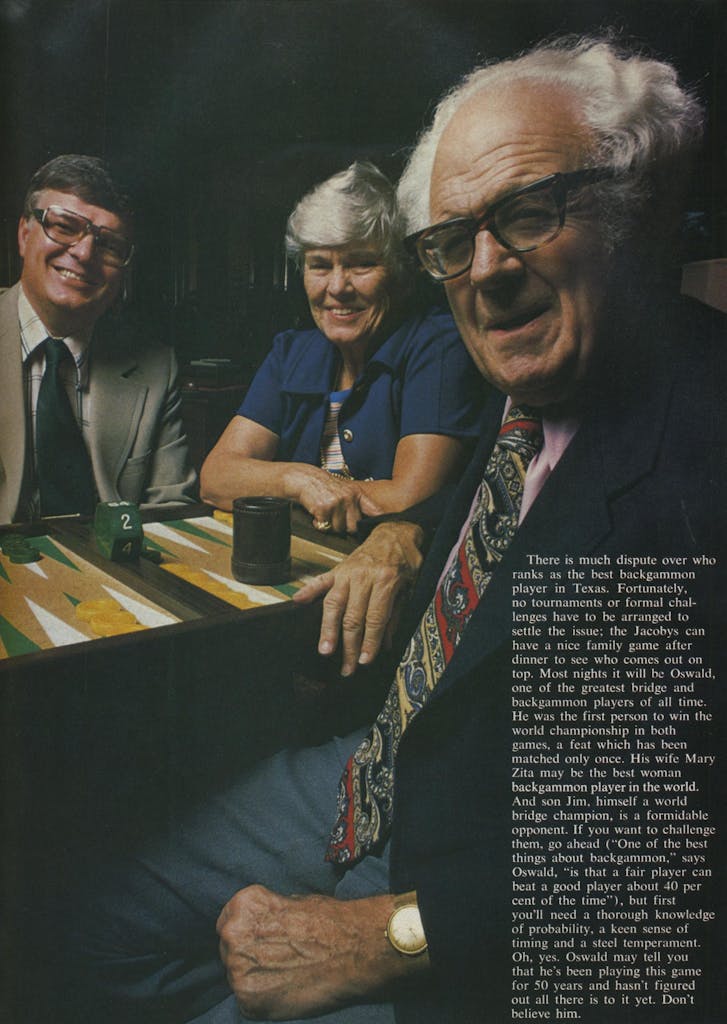

There is much dispute over who ranks as the best backgammon player in Texas. Fortunately, no tournaments or formal challenges have to be arranged to settle the issue; the Jacobys can have a nice family game after dinner to see who comes out on top. Most nights it will be Oswald, one of the greatest bridge and backgammon players of all time. He was the first person to win the world championship in both games, a feat which has been matched only once. His wife Mary Zita may be the best woman backgammon player in the world. And son Jim, himself a world bridge champion, is a formidable opponent. If you want to challenge them, go ahead (“One of the best things about backgammon,” says Oswald, “is that a fair player can beat a good player about 40 per cent of the time”), but first you’ll need a thorough knowledge of probability, a keen sense of timing and a steel temperament. Oh, yes. Oswald may tell you that he’s been playing this game for 50 years and hasn’t figured out all there is to it yet. Don’t believe him.

Watch a bridge game and chances are you’ll see players berate their partners, criticize their opponents, and vent their emotions by heaving sighs, slapping cards on the table, and scowling darkly. Watch Bobby Nail play bridge and you’ll see none of this. Nail is a pro: he makes his living playing money bridge with and against everyone from experts to players of frighteningly scant talent. Like a football coach with a reputation for rescuing a losing program, Nail has an uncanny ability to get the most out of people by making his partners think they are better than they really are. Every blunder committed by his partner comes right out of Nail’s pocket, but he is never critical. “Money bridge is like poker,” he says. “It’s a matter of patience.” Nail has won virtually every bridge honor in sight except the world championship (and he was runner-up twice), but his greatest skill is in the money game.

“A rubber bridge player is almost a practicing psychologist,” he says. “You play people as much as aces and kings.”

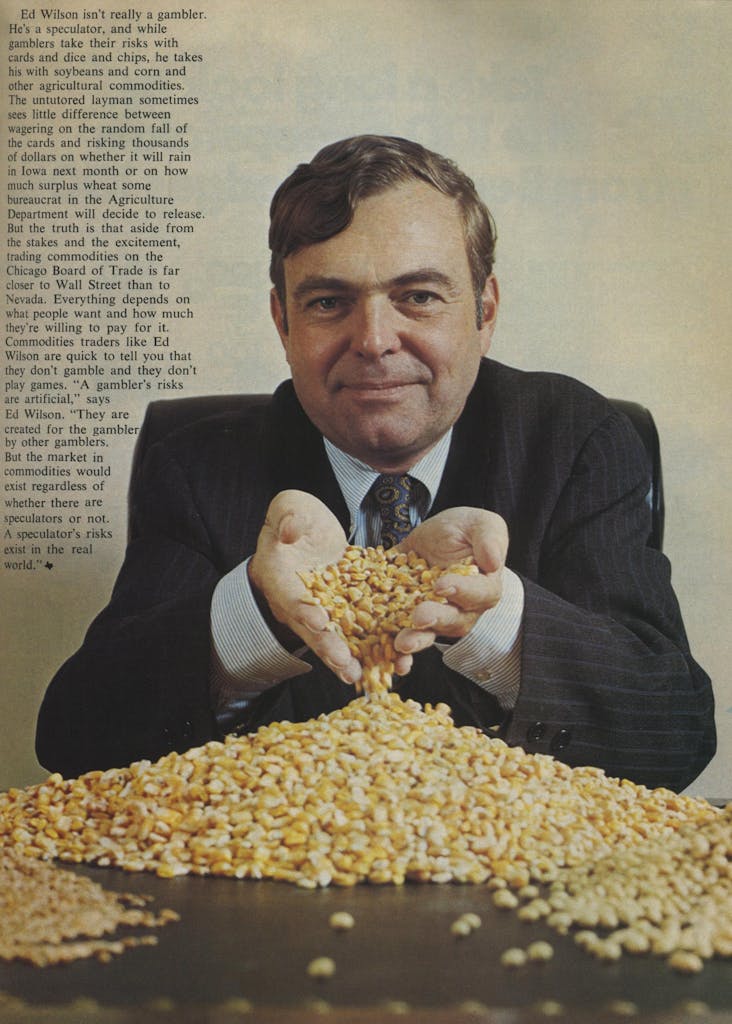

Ed Wilson isn’t really a gambler. He’s a speculator, and while gamblers take their risks with cards and dice and chips, he takes his with soybeans and corn and other agricultural commodities. The untutored layman sometimes sees little difference between wagering on the random fall of the cards and risking thousands of dollars on whether it will rain in Iowa next month or on how much surplus wheat some bureaucrat in the Agriculture Department will decide to release. But the truth is that aside from the stakes and the excitement, trading commodities on the Chicago Board of Trade is far closer to Wall Street than to Nevada. Everything depends on what people want and how much they’re willing to pay for it. Commodities traders like Ed Wilson are quick to tell you that they don’t gamble and they don’t play games. “A gambler’s risks are artificial,” says Ed Wilson. “They are created for the gambler by other gamblers. But the market in commodities would exist regardless of whether there are speculators or not. A speculator’s risks exist in the real world.”