This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A world big enough to hold a rattlesnake and a purty woman is big enough for all kinds of people.

—oldtime cowboy saying

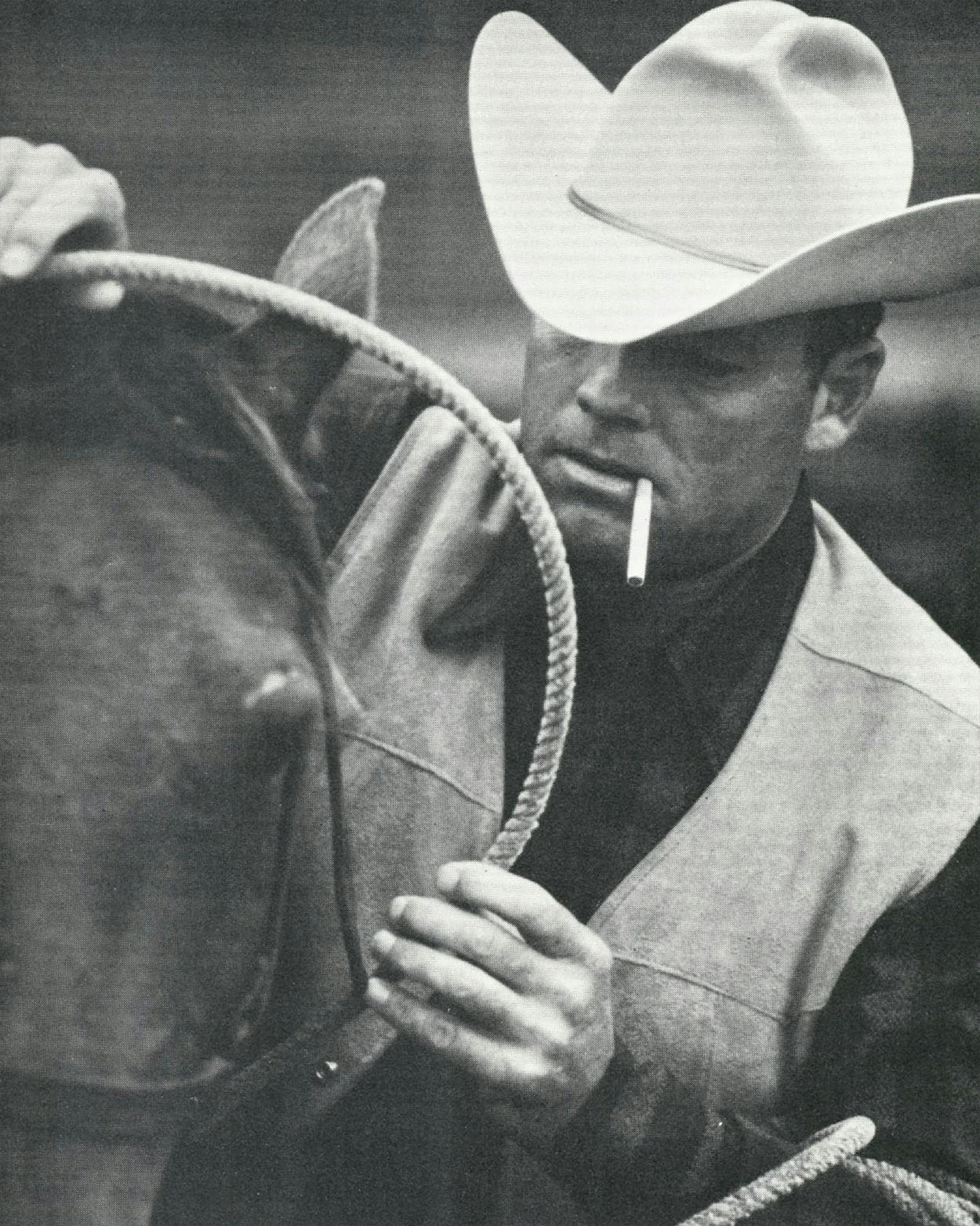

I never realized that the Marlboro cowboy was real until I read last May that he had drowned on a bucking bronco. Drowned . . . incredible . . . drowned on a nervous young colt in a newly-dug stock tank on the Bill Flowers Ranch near Old Glory, in the starkly beautiful Marlboro country north of Sweetwater. No one knows exactly how it happened; as usual, Carl (Bigun) Bradley was alone at the time.

Bigun and his daddy, Carl (Banty) Bradley, had just sold the colt to Bill Flowers, but Flowers’ foreman couldn’t handle him. Bigun saddled the horse late that afternoon, cinching the flank rope tight as he could so the horse would feel pain every time he bucked, then he rode off toward what they call Cemetery Pasture.

Bigun was 36 and for as long as anyone could remember his workday started before sunup and ended after sundown, never varying except for the two days he took off to get married, and the few times he was off in South Dakota doing a Marlboro commercial; it was seven days a week, week after week, it was the repetition as well as the work that kept him at it. But this particular day, for no particular reason, Glenda Bradley was worried. She telephoned Susann Flowers at ranch headquarters just after dark.

“You know how cowboys are,” Susann Flowers told Glenda. “You gotta hit them in the head to get them off their horse. He’ll be in in a while.” Nevertheless, Bill Flowers and his foreman would take a pickup out to Cemetery Pasture and see about Bigun. “I’ll call you back,” Susann told Glenda.

The Flowers were not only Bigun’s employers, they were his friends, and Glenda’s too, a couple about their own age. Bill Flowers was a famous rodeo roper and heir to old Pee Wee Flowers’ four-ranch spread of 80,000 acres. Bill was a real cowboy, too, but not in the way Bigun was—Bigun was a working cowboy, the son of a working cowboy, the grandson of a working cowboy, all of them born and raised on the same tenant ranch outside of Knox City, simple men working for wages and living their unrelenting existence in a world that could go mad without them knowing or even caring. Bill Flowers and Bigun Bradley had rode together when Bigun was wagon boss of the Four Sixes (6666) Ranch near Guthrie—”neighboring” they call it, helping out when there is branding or gathering to be done—there was one stretch, Bill recalled, when they were out 41 days, miles from the nearest asphalt or bathtub or woman or child or roof or television set. But there was always this difference—Bill Flowers was rich, he could quit anytime and go back to running his own ranch and rodeoing. Bigun Bradley never had time for the rodeo. And he didn’t live long enough to own his own spread.

Bill Flowers and his foreman found nothing in Cemetery Pasture, but returning to the ranch house late that night they saw something in the headlights that sent cold chills up their boots—a horse’s leg and part of a saddle blanket protruding from the muddy water near the edge of the new stock tank.

“Get the rope,” Bill yelled, jumping from the pickup before it had even stopped rolling. But they had made a mistake that Bigun Bradley would never make: they had forgotten their rope.

About midnight, Bill and Susann Flowers drove over to Glenda’s house and told her they had found the horse. There was no trace of Bigun, except his lip ice, gloves and a package of Kools. Sheriff Marvin Crawford and other volunteers had come over from Aspermont, and the dragging operation had begun. The Flowers drove Glenda and her 18-month-old son, Carl Kent Bradley, back to the ranch house where they would wait out the night.

“It was the longest night ever,” Susann Flowers would say later. “We kept hoping that maybe he had been bucked and was unconscious somewhere out there. Almost the same thing had happened to my daddy’s foreman in Pecos—they found his body in the Pecos River. We never knew what happened.”

Working in the lights of a circle of pickup trucks and a fire truck beacon, the cowboys told stories and speculated. There were three possibilities: Bigun could have been bucked off; the horse could have spooked and charged into the water, taking Bigun with him; or Bigun could have deliberately rode the bronco into the tank. “Some people think every horse will swim, but every horse won’t swim,” Sheriff Crawford said. “I’ve rode horses up to drink tubs . . . you get a bronco around water, the cinches tight up, they’re liable as not to turn and pitch. You get a horse in water, most of them will swim right across, but they’s a few’ll just turn on their sides and go straight to the bottom.”

“Bigun has been known to ride ’em into water,” another cowboy recollected. “I seen him one time after a big rain take his chestnut right into the Little Wichita, trying to get the cattle to follow him.”

Back at the ranch house, George Humphrey, an oldtime cowboy who managed the Four Sixes for 40 years (Bigun left the 6’s when George retired four years ago), told stories to the gathering of women and children. How in the old days when cattle were cheap the best way to subdue an old mossy horn was to shoot it through the thick part of the horns, aiming for dead center so that the pain would calm the steer and make it manageable. “What if you misshot?” Glenda Bradley asked, laughing the nervous schoolgirl laugh that was maintaining her. “You’d kill the animal,” George Humphrey said. “Cattle was cheap and it was an advantage to get rid of these outlaws at any price. They spoiled the other cattle. They had to be either shot or driven off.”

They dragged Bigun Bradley’s body from the tank around 2 a.m. There were signs of a blow over one eye and behind his ear. “Either one was hard enough to kill him,” Sheriff Crawford told Glenda Bradley.

Glenda went outside and cried, then she came back and helped fix breakfast.

“He preferred to work alone,” Glenda Bradley is telling me. Her voice has started to quiver, and she clasps her hands tightly in her lap. “That’s very dangerous, but he was so good . . . I think anyone will tell you this . . . he was good with horses. He just wasn’t afraid. He didn’t think anything could happen.”

We are sitting in the kitchen of her parents’ home in Westbrook, a tiny farming town near Colorado City. This is where Glenda grew up, and this is where she returned after Bigun’s death. It has been two months since the funeral: only yesterday Glenda finally forced herself back to Old Glory, and having made the trip she feels better. Old friends and memories are too dear to ignore.

“I interviewed for a job teaching homemaking at Jayton High School—that’s east of Knox City. When we were first married and Bigun was wagon boss of the Four Sixes, I taught homemaking in Guthrie. It’s a comfort to at least know what I’m going to do. People in that part of the country, especially around Guthrie, they’re not very progressive. They want things the way they were in the old times and do a pretty good job keeping it that way. Oh, they use pickups and butane branding irons, but that’s about it. At first I thought I could never go back, but . . .”

Carl Kent Bradley, called Kent, now 20 months old, rides a stick horse around the table where we talk.

“I guess he’ll be a cowboy, too,” Glenda says. “I hate for him to do it, but that’s what Bigun would want, and I know Banty (Bigun’s daddy) is going to have it that way. Bigun was never allowed to be a little boy. Banty had him out breaking horses when he was old enough to ride. I mean breaking horses . . . colts . . . not riding old nags.” Glenda says this without rancor. She is more composed now, and there is that nervous, laughing edge to her voice. “Bigun and Banty and all their people, cowboying is all they’ve ever known or wanted. To be on a horse chasing a cow was what Bigun enjoyed. Kent has already turned that way. Unless I ever remarry and my husband is so different . . . but I don’t think I’d like any other life except cowboying.”Glenda Bradley is pretty, the way a high school majorette is pretty, a way that is difficult to describe. She is what you would call “a sweet girl,” but tough and proud. As she talks about her five-and-one-half-year marriage to Bigun Bradley, she admits that she never knew him very well. No one did. “The truth is,” she says, “we never had much time together, and when we did he didn’t say much. He’d leave the house at three or four in the morning and come home after dark. He’d eat and go to bed. Every day, no days off. About the only socializing we did, every July Fourth the cowboys would take off and go to the Stamford Cowboy Reunion Rodeo.”

Bigun was a 30-year-old bachelor when Glenda met him at a rodeo dance. She was 22 and had just graduated from Texas Tech. He was the Marlboro man and wagon boss of the 6666. She had never met Bigun Bradley, but she knew him, knew him in a way that always embarrassed Bigun when she told the story.

“Bigun would kill me for telling you, but . . . well, it was a big joke at school [Texas Tech] that I liked cowboys. A friend of mine cut out Bigun’s picture from a Marlboro ad in Life magazine. Here’s your cowboy, Sis, she said. I said, Fine, I’ll just marry him, and put the picture on my dorm wall. You know, a silly girl thing. That summer another friend sent an article out of Western Horseman that gave his name Carl B. Bradley, Jr. He got the name Bigun from his Uncle Guy who use to call him Bigun and his little brother (Doug Bradley) Littleun. Actually, Bigun wasn’t all that tall, only about five-eleven, but very strong. Anyway, on July Fourth that summer I went to the Stamford Cowboy Reunion Rodeo Dance with a girl friend and there he was. He took my girl friend home that night. Two nights later, I went back to the dance and he pretty well ignored me, but he did ask me for a date.”

Six months later, after a courtship that consisted of going to an occasional cowboy movie in Bigun’s pickup, they were married. As wagon boss at the Four Sixes, Bigun was making $310-a-month, but Glenda started teaching and there was extra money from the Marlboro commercials, not all that much, but enough to get by. The Marlboro people had “discovered” Bigun Bradley while shooting some background film at the Four Sixes. He was one of several real cowboys who posed for commercials.

“One of the first things he told me,” Glenda says, “is about the Marlboro deal—he’d been offered a fulltime contract that included a part in a movie. He’d turned it down, but now, with us getting married, he didn’t know if he’d done the right thing. But he decided he wouldn’t be happy not cowboying . . . and he wouldn’t, ’cause he was good and he liked it.”

Bigun did not speak of the future, but it was his dream to someday own a small ranch. They put a little money in the bank—$120 every time Marlboro used him on TV, $1,500 for a few cover ads in Life or Look—and Bigun bought a few horses and cattle and went in partnership with Banty, who was now leasing the land where they had always worked for wages. Then the government banned cigarette commercials on TV. Glenda had to quit her job when Kent was born, and the savings account quickly evaporated. Bigun hadn’t posed for a commercial in the two years before his death. “We were barely getting by,” Glenda says. “And I mean barely.”

It cost money to cowboy. Four hundred dollars for a saddle . . . $40 for a pair of chaps . . . $100 for shopmade boots. Except on the rare occasion when he accompanied Glenda to the First Methodist Church (“He never felt comfortable in a crowd”), Bigun wore Levis, white shirt, boots, hat and, in the winter, a neck scarf. He never walked outside without his hat and boots.

“He was always giving things away,” Glenda recalls. “Bridles . . . spurs . . . If he thought someone wanted his boots he’d sit down and take them off right there. That’s just how he was. He was the most patient, most courteous man I ever knew. Even after we were married and had the baby, he would still open doors for me—yes ma’am and no ma’am—he wouldn’t even take a serving of food off the table until I’d served myself first. That’s the way May (Bigun’s mother) raised her two boys. Even after we were married, whatever Mama and Daddy said do, he’d do, regardless of my opinion.”

J. Frank Dobie once described the cowboy as “a proud rider, skilled, observant, alert, resourceful, unyielding, daring, punctilious in a code peculiar to his occupation, and faithful to his trust.”

That’s a pretty good description of Bigun Bradley.

Joe Thigpen, the young county attorney of Stonewall County, tosses a pack of Kools on his desk and tilts his straw hat on the back of his head. In his wilder days, before he finished law school, Thigpen worked for Bigun Bradley at the Four Sixes.

“I knew about the Marlboro cowboy—everybody around here did,” he tells me. “It was a thrill meeting him.” The first thing Bigun Bradley did was send Joe home for his saddle and bedroll; it hadn’t occurred to Joe that he would need a bedroll. This was in 1968, the Four Sixes still had a chuck wagon drawn by four mules, a kind of traveling headquarters; they slept under the stars, bathing maybe twice a month. The wagon was already out when Joe Thigpen hired on, and they stayed out another two-and-a-half months.

Joe Thigpen tells me: “I never met a man as patient and completely dedicated as Bigun. I never knew a man who worked harder. I don’t think he ever asked for a day off. He’d wake me up every morning and tell what we had to do that day. Then we’d do it.

“Now I’m not saying he couldn’t be tough on you. There was one day we were flanking cattle and I was always in the wrong place, spooking the yearlings. Bigun roped this calf . . . must of weighed 450 pounds . . . and said, ‘you been messing up all day so you just flank (ie: throw) this one by yourself.’ Now there’s no way one man can throw a 450-pound yearling. The calf stepped on my toes and like to of broke them. I was sweating and puffing, all the way given out—never did get that yearling down. Another fellow finally had to help me. But Bigun wasn’t doing it for meanness—he was teaching me a lesson.”

I asked Joe Thigpen what it is that makes a man cowboy. He thought for a while, then said, “I can’t tell you exactly, but I loved it better than anything I’ve ever done. You’re outdoors, doing what you like to do. I probably never would of gone back to school, except Bigun told me that’s what I ought to do. It was the best advice I ever got—a cowboy can’t afford a family.”

Thigpen took a check stub from his wallet and showed me his final month’s pay at the 6’s—$162.50. Then he offered me a Kool and told me a story: “We had about 125 horses in the remuda, we were moving them one day . . . I guess we must of rode 22 miles . . . me being the low man on the totem pole, I had to ride drag . . . you know, back at the end, hollering and yelling and pushing horses. It was just dusty as the dickens. I was trying to smoke those Marlboros . . . I thought that’s what I oughta smoke . . . but they were burning me up . . . I’d take one puff and throw it way. That’s when Bigun came riding back. He didn’t say a word. He just took a pack of Kools out and offered me one.”

“‘That’s when Bigun came riding back. He didn’t say a word. He just took a pack of Kools out and offered me one.'”

Joe Thigpen takes another cigarette and shakes his head. Hard to believe. Hard to believe that a man who knew so much about horses could be killed by one. “It’s something I’ll never be able to get out of my mind,” he says.

It doesn’t take long to tour the Old Glory community, but the tour is fascinating. Seated in a flat, green valley of windmills and skeleton mesquites that have been poisoned because they take too much water from the land, Old Glory is an abandoned cotton gin, a general store and post office, and a scattering of quaint old homes. One of the homes is the old Raynor Court House which sits now like a feudal castle on a high mound. It looks like the house in the movie Giant I think as I drift below on the farm road from Aspermont, and it turns out they modeled the movie set after the Raynor Court House. An old couple whose name I didn’t catch live there now. No one ever goes up there, they told me at the general store.

The Germans who settled here called the spot New Brandenburg until World War I when, in a fit of patriotism, they decided the name sounded too un-American and asked the oldest woman in town, Mrs. Weinke, what they should do about it. She told them to change it to Old Glory, and that’s what it’s been ever since.

I’m in the passenger side of a station wagon with Susann Flowers and her two young boys. Bill Flowers has been off since before daylight, buying cattle in a market that is on the verge of Nixonian panic, and Susann is showing me the ranch. We drive through Cemetery Pasture, where the old German cemetery is preserved by a fence—judging from the grave stones, an unusual number of children died here in the late 1800’s, a time of epidemic, perhaps—and now we slow down near the stock tank where Bigun Bradley died.

“You know what I always think when I drive by here?” Susann Flowers says. “I think about Bigun’s hat. We never found it. It’s down there somewhere.

“Bigun couldn’t swim, you know. Neither can Bill. It scares the hell out of me to see them swimming their horses, but they do it all the time. There’s no reason for it, it’s just something they do. We’re not supposed to question what happens on this earth, but I can’t help wonder what happened that night. He could have been bucked, or the horse could have gone into the tank, but I can’t help feel that Bigun rode in on purpose.”

We stop in a warm summer rain while Susann fills the tank of her station wagon from a gasoline drum near the foreman’s house. In an adjoining pasture there is a modern house trailer where old Pee Wee Flowers still comes occasionally to play dominoes with the hands. Susann wants to change the name of the Bill Flowers Ranch to “something Spanish,” but Bill and Pee Wee won’t hear of it. Susann Flowers doesn’t want her two children to cowboy, but that’s what they will do—cowboy like their daddy, not like Bigun Bradley. Meanwhile, Susann is organizing a college scholarship fund for little Carl Kent Bradley.

“Bigun wasn’t afraid of anything,” she says as we drive back to the ranch headquarters. “I heard him say one time—he was talking about this cowboy we all knew—Bigun said: ‘Charley’s afraid of dying.’ It was something Bigun couldn’t understand. He was tough as hell—that’s what he was. Yet he was the most considerate, most dependable man I ever knew. I’d known him for years before he stopped calling me Mrs. Flowers—and I was younger than he was.”

Jeff Flowers, age 5, tells me what he remembers about Bigun—Jeff remembers Bigun brought him a tiny rabbit they caught in post hole. Jeff wears spurs on his little boots and has two horses. They’re not very good horses, he tells me.

In a driving rainstorm, I turn toward Knox City, thinking about women and glasses of beer.

I stop to consult my crude map. The rain has stopped and the sun is slipping behind Buzzard Peak when I find the muddy, rutty, unmarked road which leads to the tenant house where Bigun and all his people grew up—the ranch that Banty Bradley now leases. A sign at the main-gate cattleguard identifies this as the “General American Oil Co.,” and it is still another ten miles to the house, which sits on a crest overlooking miles of green hills and naked brown peaks. Fat quail and jack rabbits big as dwarf deer bounce in front of my car, and horses and cattle look me over without judging my intentions.

Banty and May Bradley are out by the stable, hoeing weeds. There are miles of weeds, weeds far as you can see, but the apron of ground around the stable is clean as a dinner plate. They hoe patiently, like people listening to the radio, like they don’t care if there is an end to their struggle.

Banty is a short, husky, red-faced cowboy with wide spaces between his teeth to spit tobacco through. They say Bigun was a younger exact replica of his daddy. May, though, is pure Texas mule-iron, a lean, severe, outspoken woman who hasn’t smiled since Christmas. There is no telephone here; I couldn’t call in advance, and now they decline to be interviewed. I stand by my open car door, asking questions, while they go on hoeing, then I get an idea. I tell them that I saw “Sis” (Glenda’s nickname) yesterday, she says hidy and she’s feeling much better. She’s got a new teaching job at Jayton. Banty and May brighten as I play them a part of the tape I did with Glenda.

“Did you see Bigun’s boy?” Banty asks, eagerly breaking the silence.

I describe meeting Carl Kent Bradley.

“That baby of Carl B.’s is a natural-born cowboy,” May says. May is the only person I met who doesn’t call her son Bigun. She calls him Carl B. “Look at him ride his rocky horse—natural saddle gait.”

“It’s getting harder,” May says, “harder to go on. There is very little neighboring anymore. It’s every man for himself. You used to be able to tell a cowman by his boots,” she tells me. “If he was worth a speck, he had $100 shopmade boots. Now days, you tell a cowboy by his woreout brogans. Real cowboys can’t hardly afford boots. One thing about Carl B., he couldn’t care less about money. There was a pattern in his life. Things came his way. He didn’t ever ask for things, we taught him that, but things came his way. He didn’t ask for all that publicity. He got plenty of it, but he wasn’t a seeker.”

May does most of the talking, deferring occasionally to Banty, reminding him of a particular story. They tell me about Banty buying Bigun’s first saddle when Bigun was three. May talks about their other son, Doug, how Doug never wanted to be a cowboy. Doug drives a bulldozer. Doug was always building things, while Bigun played cowboy. Blocks and stickhorses. “Bigun wore out many a stick horse before he could ride,” May says. “He’d play cowboy and Doug was always his calf. Doug had all the hide wore off his neck by the rope.”

“‘You used to be able to tell a cowman by his boots. Now days, you tell a cowboy by his woreout brogans. Real cowboys can’t hardly afford boots.'”

At May’s urging, Banty tells me about Bigun snitching the latch pin off the barn door, and how Bigun was afraid of the dark but Banty made him go back alone in the dark and replace the latch pin. Bigun never again messed with the barn latch. They tell me about the agonizing weeks it took before Bigun would mount his first wild bronco. And how, once he had done it, he never stopped. Why does a man cowboy? I ask. Banty grins and points to his head, as though to say that’s where his heart is. If Bigun was as good as they say, and I believe he was, why didn’t he join the rodeo circuit? “Too many people,” Banty grins.

Later, May takes me up to the house and shows me her clippings, the clippings describing the deeds of the Marlboro cowboy. Best all-around boy at Knox City High, senior class favorite, FFA president, co-captain of his football team, honorable mention all-district. Carl B. (Bigun) Bradley, Jr.’s plain moon face, his eyes tinted Paul Newman blue, barely seen in the shadow of his hat, smoking what is alleged to be a Marlboro cigarette. Why? Why would Marlboro pick Bigun Bradley? I guess because they saw he was a real cowboy.

There is a Marlboro sunset as I slide back along the mud road and turn toward Guthrie. Two horses in the road ahead turn flank and trot off into the brush. There is a silence that lasts forever—if there were such a word, forever. A windmill is silhouetted against the dark fire of the horizon, and I can’t help thinking it’s a long way home.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads