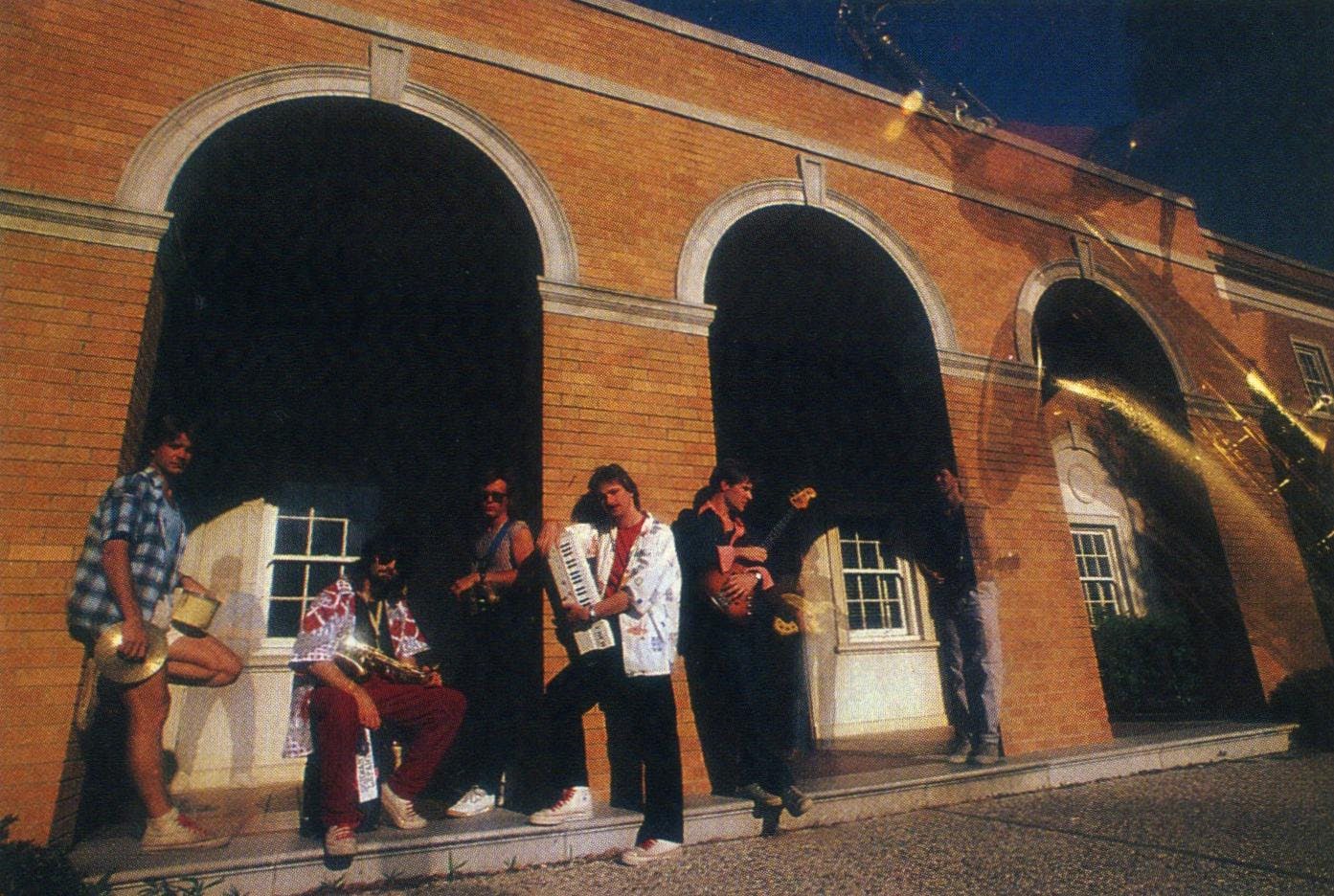

Even in Denton, a town noted for unusual bands, Brave Combo seemed unlikely to succeed when Carl Finch formed it in 1979. Was the world ready for a nuclear polka outfit? When the members of Brave Combo made their first trip to New York, their van broke down five times, they lost $3000, and they suffered the ignominy of being mistakenly billed as an Irish folk group when they stopped to play a pickup gig at the Raleigh Hilton Hotel in North Carolina.

By 1985, however, Brave Combo had helped inspire a minifad. Rock bands in Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and New York were dabbling in polka; SCTV’s Schmenge Brothers were starring in a cable television special called The Last Polka; and “Weird Al” Yankovic was taking accordion music to the rock audience. And Brave Combo? It was still a cult group, albeit bigger than ever. In Denton the band members are considered conquering heroes.

Denton is a country town of tree-lined streets and impressively maintained wooden houses about 35 miles north of Dallas. It is also a music town unlike any other in Texas and possibly in the country. Chalk that up, most certainly, to North Texas State University’s celebrated music department, which attracts talented jazz and classical students with a program that sharpens their individual skills to a professional level while leaving many of them ambivalent about how best to apply those skills. They become musical misfits, sometimes consciously, sometimes not. The dilemma of art versus commerce is one that every aspiring band faces, but it is heightened in this college town. The first thing you notice about the off-campus club scene is its depth and variety. The second thing you notice is how far outside the commercial mainstream most of the bands are and how many of them break up without leaving town to test the national waters. Denton bands won’t go to the music industry, and the industry won’t come to them; there are no significant managers, agents, publicists, producers, or recording studios in this city of 58,000, but there are more bands than anyone knows what to do with.

Denton has long accommodated an improbable mating of college-town artiness and North Texas conservatism. In the sixties, one of the state’s first head shops opened there; yet voters in 1982, led by a large and vocal Baptist faction, revoked extended-hours drinking laws that had been in effect since 1979. Clubs, which can serve no hard liquor unless they charge private membership fees, once again have to close at midnight during the week and at one o’clock on Saturdays, a situation that presents obvious problems for a music scene. But life in Denton can be easy. Thanks to cheap rents and a laissez-faire attitude from the rest of the town, a college subculture of ex-students, hangers-on, and bohemians—particularly musicians—has remained in Denton. And the NTSU music department continues to set the tone for Denton bands, if only because so many of their members were once trained there.

Nearly a fourth of NTSU’s 1600 music students are in the jazz program, which began in 1947 and is the largest such university program in the nation. Under Leon Breeden, the director of jazz studies from 1959 to 1981, NTSU’s jazz program and its One O’clock Lab Band earned a national reputation. When Breeden first came to Denton, he was advised not to use the word “jazz” in department literature because of its obscene connotations. He soon had his students writing and playing modern jazz when other schools were still mired in the swing era. Yet even when his hard-nosed program was at its most avant-garde, the emphasis was always on technical proficiency. As Breeden’s successor, Neil Slater, explains, the super-competitive program also requires students to learn to play a piece of music quickly, so they can fit into a variety of contexts. NTSU grads go on to win seats in touring groups (especially “ghost bands” like those of Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller) and hotel and nightclub orchestras; become session players in recording studios, doing jingles and working as sidemen; or teach. Though teaching jazz, a music built around spontaneity and improvisation, may seem contradictory, that is exactly what NTSU does.

Keeping a band together long enough to build an audience, which is hard to do anywhere, is even harder in Denton. The best musicians are constantly leaving town for good-paying gigs as sidemen, and the lingering ethic of the music school is so competitive that players often think more in terms of getting ahead individually than of subjecting themselves to something as inherently egalitarian as a rock band, where emotional content is placed above technique. That individualism may be the reason that a nationally ranked band has never emerged from Denton. Instead, NTSU has produced such individuals as Pat Boone, Trini Lopez, Michael Murphey, Steve Fromholz, Lou “Blue” Marini (Saturday Night Live and Blues Brothers saxophonist), Marc Johnson (bassist for the late pianist Bill Evans), and Lyle Mays (Pat Metheny’s pianist).

Those who do venture into bands tend to form rock and pop groups; even with all those jazz students nearby, rock is what draws crowds. The key clubs in Denton—the Library in the Fry-Hickory area and the Rock Bottom Lounge on campus—can choose from among a couple dozen bands made up of talented players. With so many musicians in their audience, Denton performers are less concerned with putting on a show or getting across an idea than they are with demonstrating that they have “good chops.” The tensions between making music for a living and making music for its own sake transfer from the classroom to the club, from jazz to rock. Denton musicians are technically superior to most rockers, and they worry about selling out that talent; they want to make it, but usually on technique alone. They’re reluctant to consider having an image, a concept, or even an identifiable group sound—all of which the record business more or less requires from new bands.

David Williams, a 26-year-old native of Naples, formed the Frenetics, Denton’s first punk band, in 1980 and now fronts a three-piece outfit called Self Is on the Throne. Williams is a primitive by Denton standards, and proud of it. He is a student in computer science; his closest brush with formal music training was eight years of piano lessons as a child. He doesn’t hang out much with other musicians, figuring that he’s too abrasive for their laid-back personal styles. Williams writes cryptic lyrics, but his songs hit home viscerally—taking tips from the brittle rhythms of Gang of Four and the Talking Heads as well as from the blare of the Sex Pistols and the Clash.

“There’s always been this cult of people in Denton who were admired as technicians, as players,” he says. “Some are from lab bands, and some are mavericks—the kind of guys playing in four bands at once. I was always left cold by those guys. There aren’t many extremes of emotion in Denton. Most people are in such a pot haze, it’s all leveled out. Nobody has any opinions here because they’re all wonderful people and they all love music. They just seem like hippies to me.”

Most Denton musicians speak approvingly about the ability of their colleagues to adapt to any setting; it is considered to be a sign of well-roundedness, of overall ability. But for a hard-core rocker like Williams, who is committed to the idea of a band sound and stance and to music as a way of life, players who do anything equally well, who can fit in anywhere, have no passion or musical allegiance. And that, Williams suggests, is another reason Denton music doesn’t travel.

The experiences of Schwantz Lefantz exemplify the Denton dilemma. Schwantz grew out of dorm jams around 1972. A fusion unit serving as a vehicle for ambitious songwriters Ed Loftus and Doug Frantz, the group was once considered somewhat daring, as bassist Steve Carter puts it. “Our original stuff was more complex, more notes and time changes,” Carter says. “Our copy material was weird stuff by the Fugs, Frank Zappa, or from bebop.” The group’s music today, though still making passing references to jazz, is stylish, blow-dried pop that Loftus compares to that of Steely Dan and Phil Collins.

“I was a composition grad with several years of really rigorous training, and when you finally do get out into the entertainment business, it’s a real blow,” Loftus says. “You spend six years getting your music together, and the public wants to hear ‘Proud Mary.’ It takes a while to be able to match your expertise with what people like. We’ve been able to survive by adapting. So it’s not simply a matter of going pop. It’s just not that simple.”

The members of Schwantz were recently seen hobnobbing with Ed McMahon as contestants on TV’s Star Search, a career move that left most of Denton snickering. Now the group is stuck, in Denton terms, with the worst of both worlds. It has lost the respect of its fellow players, and it is still not off the midwestern bar circuit. Schwantz tried to sell out and found that nobody was buying.

“Sure we’ve made some compromises, but some of our things are still pretty authentic,” says Carter. “We still have enough integrity to stay close to our original idea. We compromised, but we didn’t sell out. Still, I would like to make a living from this band, and that has yet to happen.”

Brave Combo does make a living, however modest. Finch, a Texarkana native and graduate of the NTSU art school, is the most pop-savvy musician in Denton, no matter how uncommercial his music might appear to be or how much he mistrusts the record industry. He is also a tireless and good-humored self-promoter; it was Finch who dubbed Brave Combo’s sound “nuclear polka”—such an effective tag line that it couldn’t be shaken, even after the band had outgrown it.

Finch had taken to polka as a reaction against the pomp and pretension of rock and jazz; the group offered a deadpan, slightly surreal mix of polkafied trash- rock classics (“In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida”) and rocked-up polka standards (“The Beer Barrel Polka”) to audiences that might be new wavers at one venue, traditional polka fans at the next. The music was as infectious as it was satiric, but most of all, it was audacious—Finch recalls an early review describing Brave Combo as “another loony Denton band that would stay together awhile and then break up.”

Brave Combo was willing to hit the road, though. Its initial swings into the Northeast may have been financial disasters, but they earned good reviews. Even Rolling Stone took notice, which rarely happens for bands without major-label backing. Brave Combo also financed its own first record, on Finch’s independent Four Dots label. As the group discovered Tex-Mex polkas and then other ethnic musics from Latin America and Africa, the parodies and novelty songs fell by the wayside. Today Brave Combo has a tenacious, if small, national following; it has released a total of three albums and two EPs on Four Dots. The records still don’t make money, but they do help spread the band’s name.

“What it gets down to is marketing, if you want to stick with it long enough. The problem is you can’t stick to Denton and make money. And I don’t know why more Denton bands don’t play out more,” Finch says. “You’ve got to be willing to go other places and lose money and build an audience. Most Denton bands think they have to make money or they won’t travel, but that’s not how it works— at least that’s not how it works at first.”

In one sense even Brave Combo has been outmaneuvered by Hollywood. Just when the group was growing away from its most gimmicky material, accordionist “Weird Al” Yankovic (author of “Dare to Be Stupid” and similar hits) was taking the most obvious aspects of Brave Combo’s style, packaging them for MTV (of which Finch is especially contemptuous), and parlaying them into a lucrative career.

The members of Brave Combo have no complaints, though. They still have enough of that Denton purism left in them to believe that if that’s what it takes to make it, they would rather remain the kind of band more people have heard of than have heard. More than any other group, Brave Combo has made peace with the Denton dilemma. While most local musicians play in several bands out of economic necessity, some Brave Combo members have side projects, strictly for pleasure. Drummer Mitch Marine indulges in his percussion ensemble (the Seven Powers of Africa), and horn man Jeffrey Barnes in his brass band (Banda Eclipse). The group’s musicians are about the only ones in town who neither attend school nor hold part-time jobs. And in Denton, that’s the best of both worlds.

- More About:

- Music

- Business

- Music Business

- Jazz

- Denton