CHAPTER ONE

In West Texas where Jacob Trace made his way toward a dry camp after a fruitless day trailing a mountain lion, September dusk brought little relief from the heat and his mule kicked up dust from the parched, cracked earth. In Houston where Randolph Morgan, assistant director of the North American Zoological Association, and bored reporters awaited the arrival of World Air 17, dusk was hardly noticeable in the warm blanket of fog that wrapped the city.

At 24,000 feet and holding, World Air 17 was at last out of the storm. The flight across the Atlantic had been rough, even for the experienced crew aboard World Air 17. Storms had forced a detour, and severe turbulence had placed the DC-10 at the edge of control. A downdraft had dropped the wide-bodied jet several thousand feet. The altitude loss took seconds but gave the passengers time for screaming, vomiting, hyperventilating, and discovering suspect hearts.

The plane had groaned like a woman in labor and bottomed out with a jolt that tested every weld in the airplane and destroyed some electrical circuits, none of them crucial. The passengers had been belted down, but one stewardess, Claudette, had been assisting a sick child just aft of the first-class cabin when the aircraft went into its Jesus Christ mode, and she had been slammed against the overhead and knocked unconscious. The passengers wanted their feet on the ground. However, World Air 17 had arrived at Houston to find the airport wrapped in dense fog.

“World Air 17, this is Houston Center. Do you wish to declare an emergency?”

“Negative, Houston.” Captain Robert Hansen had never declared an emergency in a long career, and he had no intention of declaring one now. He wanted everything routine, another flawless flight under the hands of Smiling Bob, doctor of the air. “Had a little turbulence. Stewardess with minor injuries. We’d like a priority landing.”

“Houston still below minimums, expecting momentary improvement. Continue pattern. You’ll be first to land.”

“Roger. And thanks.”

“Darryl,” the captain said, “everything’s under control here. Amble aft, tell the folks back there that we’ll be landing number one as soon as we get clearance, and have the stews break out the medicinal alcohol. Check on Claudette and be sure the stews have cleaned up any blood. It only takes a drop to panic passengers when they’re scared.”

Darryl nodded. He had occupied the copilot’s seat for half a dozen years and this had been his worst trip. He wouldn’t admit it once he was on the ground, but he had made his peace with God, certain the airframe would warp under the stress. He had often yearned for the newer, faster airplanes–the Ten had been approved by the FAA in 1971 and, twenty years later, World Air and some others were still flying them. Today he was grateful for the tough, reliable, and unglamorous Ten. He removed his headset and harness and left the flight deck to smile at the passengers and assure them they had the best captain in the sky and would be safely on the ground by the time they finished their drinks.

He was pleased to see there was no blood in the cabin. Claudette had a cut on her head that would require stitches and was calm but dazed. He told Susan, chief stewardess, to keep her quiet and out of sight of the passengers. He continued aft, smiling, reassuring, promising they would be landing soon. The flight attendants had done a good job helping those who were bruised or sick and cleaning up the mess.

On his way back to the flight deck Susan reported that the elevator was not in the full up position and seemed to be jammed. Darryl opened the door of the elevator and leaned inside to try the buttons. Nothing. The elevator was at an awkward angle in the shaft and he jumped back when something shifted in the pressurized cargo compartment below. Structural damage. Forcing a smile, he returned to the cockpit to tell the captain.

* * *

In Moscow, the Iron Curtain had cracked and strange winds blew through the open spaces–democracy, chaos, anarchy. Mikhail Kuzakov was not a politician; he was a bureaucrat. He had done as he was told and he had done well, director of the Moscow zoo. Things had been simpler when the Communists ruled. Logical, practical, hard. Then, he had known what to say.

He did not know what to say when the minister telephoned to report the police had found Adja Bayan dead. The old man tended felines at the zoo. “There was a cat in his apartment,” the minister said.

“I don’t understand.”

“Perhaps you know that before democracy,” the minister said the word carefully, “scientific experiments were conducted on zoo animals.” Unofficially, Kuzakov had known about the secret labs and faceless scientists who experimented with infectious diseases but the labs had been dismantled, the records destroyed, the scientists removed.

“Adja Bayan’s death seems normal but suspicious. You will take appropriate action.”

Accompanied by a technician, Kuzakov went directly to the remaining lab in the wooded area behind the zoo, the lab for testing samples from sick animals and preparing their medicines. Everything seemed to be in order. He led the technician to the small building shielded from view by the antelope compound and the patch of woods on the back side of the zoo on Bolshaya Gruzinskaya Street. Adja had a single room with a cot, washstand, kerosene stove for cooking, a table, and one chair.

They searched for the cat until they found it hiding under the bed. The technician, a small man with folds of skin in his face, slipped a net over the cat. The cat flattened its ears and hissed, but the technician, who was wearing thick leather gloves, grasped the cat across the shoulders and lifted it from the net. Taking the cat’s head in his other gloved hand, he twisted until the vertebrae cracked and the cat went limp. He dropped it into a bag and and the two men left the room as they found it. Kuzakov had done something. Would someone tell him whether he had done the right thing?

* * *

The captain glared at Darryl. “I didn’t send you aft to panic the passengers,” he growled. “One of the food pods in the galley must have torn loose, knocked out some circuits and jammed the elevator.”

Darryl looked at Kenneth, the thin, balding second officer, but Ken was glued to the instruments. Susan opened the door and walked onto the flight deck. “We have the passengers settled down with a drink in their hands. Claudette has a concussion but we have the bleeding stopped.” Hansen nodded. “Captain, there’s something loose below.”

Hansen looked at Susan to demonstrate his contempt of crew members who created panic. “We’re going to be on the ground in five minutes. Now get a grip, and that goes for your crew too.”

“Captain, there is something moving in the galley,” Susan repeated. “I can hear it through the dumb waiter. I can smell something burning. Something electrical.”

“Some of the circuits are out,” Hansen snapped. “Nothing important. Probably the ovens.”

Hansen didn’t like excitement in a crew member, and he didn’t want the crew running back and forth through the cabin when the passengers were watching for any sign of alarm. The attendants had been pushed to the limit with sick and frightened passengers, but if Susan said something was moving in the galley, something was moving. And if the panicky passengers caught a whiff of smoke it would take the whole crew to calm them. Susan waited, silently insisting that he do something. “Darryl, go back there and hold her hand,” Hansen said without looking at him. “Before she upsets the ‘official’ passengers.”

Susan led Darryl to the dumb waiter shaft. “Listen,” she said.

Passengers within line of sight of the two watched them intently. He leaned into the dumb waiter shaft and sniffed. Nothing. The captain was right, probably the ovens. He listened, trying to identify the sound. It wasn’t metal to metal or constant like something banging against the bulkhead. It was a soft, shuffling sound, one Darryl had never heard on an aircraft before.

The emergency hatch was on the starboard side at the front of the first-class cabin. There was no way to open it without creating fear in some passengers, but he had to know what was loose. They couldn’t have something rolling around on their descent into Houston. “I’m going to open the emergency hatch and take a look. Want to give me a hand?”

Susan nodded and followed Darryl to the small emergency hatch in the first-class section. The hatch opened into the forward part of the twenty-foot galley. The elevator shaft, flanked by movable bulkheads separating the galley from the forward cargo hold, was at the aft end. Between the two bulkheads, lining either side of the galley, were the heavy food pods.

Darryl stopped at the emergency hatch in the aisle beside one of the first-class seats and smiled at the heavyset, orange-haired woman who occupied it. She was not amused. Susan came to his aid. “If we’re going to have any coffee, we’re going to have to get into the galley through here,” she said. “And the captain wants his coffee.”

“To hell with the coffee,” the woman said. “Tell the captain to get this son of a bitch down.”

Darryl was startled, but he broke into a wide grin. “Yes ma’am, I’ll tell him. Just after I’ve given him his coffee.”

“Orders are orders,” Susan said, in her sweetest official voice.

“I’ll have some of that coffee,” said a thin, bald-headed man sitting next to the fat woman. They did not know each other, and they had been together long enough to know they did not want to know each other.

Darryl knelt in the aisle, pulled back the carpet covering the hatch, hooked his finger in the folding ring and looked at Susan. If smoke boiled out of the hatch it would be her job to control the passengers. Susan nodded.

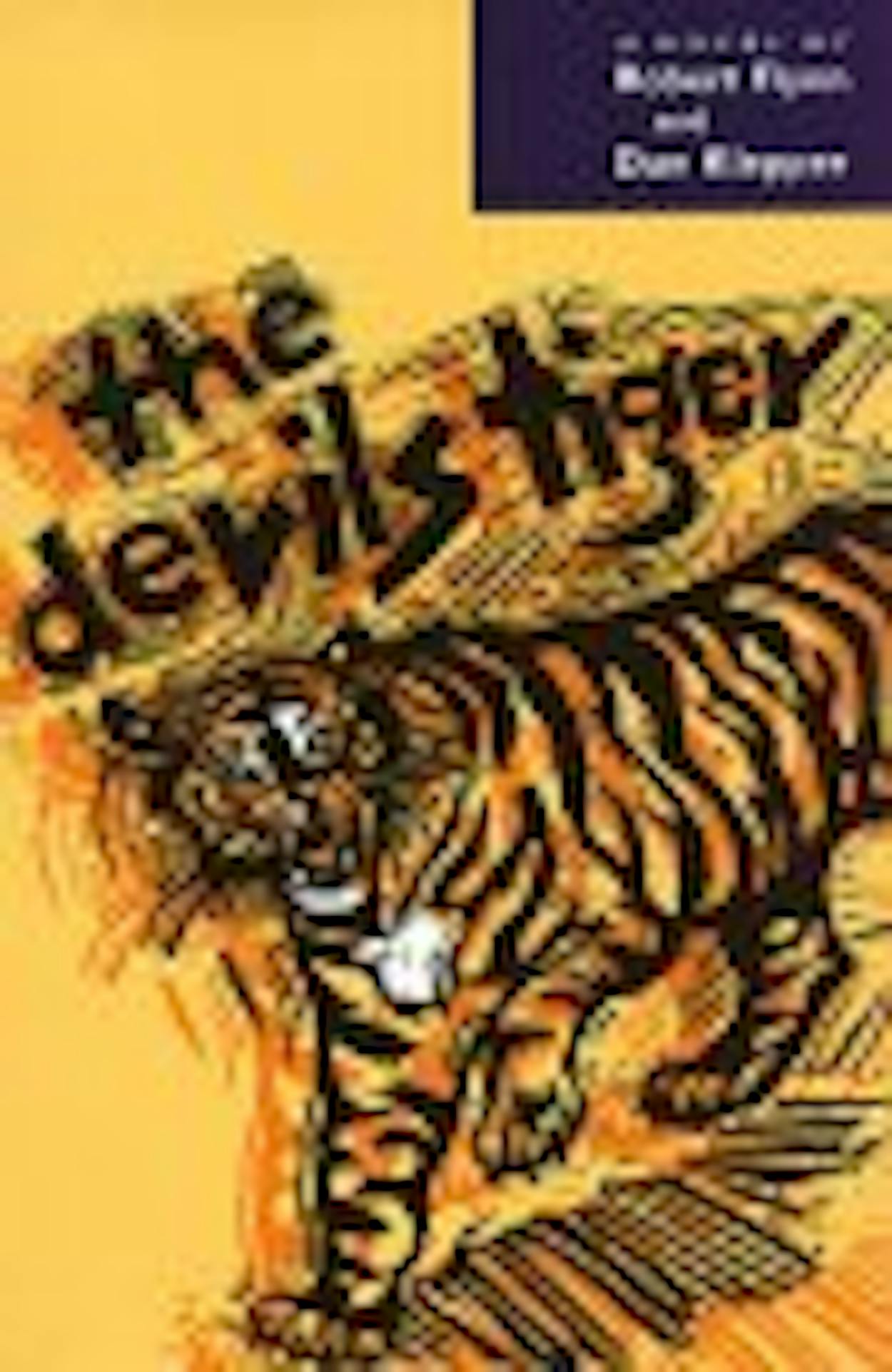

Darryl opened the hatch. No smoke, thank God. He could see nothing but the bare deck at the foot of the ladder eight feet below. He bent over, stuck his head into the hatch for a better view of the galley and looked into the unblinking eyes of a Siberian tiger.