THREE TOY BATMAN FIGURES perch atop a word processor in the small, cluttered El Paso office of Abraham Verghese, and a dozen or so Robins, Jokers, and Batmobiles line the office windowsill. “My kids got tired of them after a while,” he says, “so instead of throwing them away, I just brought them here.”

Like the caped crusader, the 42-year-old Verghese lives a dual existence: doctor by day and writer by night—or vice versa, depending on what day it is. Verghese the writer produces articles and essays that appear in periodicals like Esquire and the New York Times and powerful, disturbing short stories that grace the pages of The New Yorker, Granta, and various small literary magazines. My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story of a Town and Its People in the Age of AIDS, his highly acclaimed 1994 memoir about his experiences treating AIDS patients in rural Tennessee, was nominated for the prestigious National Book Critics Circle Award and was praised by New York Times columnist Frank Rich as “one of the most affecting [books] the plague has created.” As a doctor, Verghese (pronounced “Vur-geese”) confronts villains like AIDS, cancer, and tuberculosis several times a week when he and a gaggle of white-jacketed medical students look in on patients at El Paso’s R. E. Thomason General Hospital, the teaching hospital of the Texas Tech Health Sciences Center, where he is a tenured professor of internal medicine and the head of the infectious diseases and geriatrics divisions. Located in the heart of the barrio, Thomason General is the only public hospital for a city of nearly 600,000, as well as for an unknown number of Juárez residents.

Not all of what Verghese sees and hears at work shows up in his fiction; still, the life-and-death atmosphere he experiences there nourishes him in ways that may not be immediately obvious. And he’s equally invigorated by El Paso itself: Something about this gritty, history-laden border city nourishes him—just as it does Cormac McCarthy and Dagoberto Gilb and Rick DeMarinis and Benjamin Sáenz and numerous other members of what may be the most vital writing community in Texas. Why El Paso nurtures writers is something of a mystery, although Gilb, who moved to the city from Los Angeles in 1976, thinks he knows. “It’s a good place to go to disappear,” he says. Indeed, with its relentless sun and hard-edged landscape, its restless mix of cultures, and the whiff of danger emanating from Juárez, El Paso is to Texas as Albert Camus’ Algeria was to France: a fine place for writers to confront life boiled down to its existential essence.

It’s certainly that for Verghese, who was born in Ethiopia to Indian parents, immigrated to the United States in 1974, and has lived in El Paso since 1991. “I came here for a job interview and absolutely fell in love with the place,” he says. “Walking over to Juárez, suddenly I was in the Third World again. With my skin color, I could disappear. There were so many different mythologies here—Spanish conquistador, Pueblo Indian, Cormac McCarthy’s Wild West—but there was plenty of room for an African-born Indian to weave his own myth.”

Like V. S. Naipaul, another writer with Indian roots, Verghese navigates in the interstices between borders. His parents were teachers in Kerala, a state in southern India, when Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie visited the subcontinent in the early fifties. Selassie was so impressed with the high level of literacy in Kerala that he recruited some of its teachers, among them Verghese’s parents, to move to his country; Verghese was born in Addis Ababa, the capital city, in 1955.

As a teenager, Verghese thought he might become a journalist, but his parents told him that young Indian men were expected to pursue more respectable and remunerative professions—the law, perhaps, or medicine. He remembered how he had been inspired by Of Human Bondage, Somerset Maugham’s autobiographical novel about a young Englishman who in medical school finds, in Maugham’s words, “humanity there in the rough, the materials the artist worked on.” Verghese entered medical school in Ethiopia when he was sixteen but left during his third year, after civil war had toppled the emperor and the country spiraled into chaos. He joined his parents in America, where they had settled three years earlier. “It was a terrible feeling, being labeled an expatriate in your own country,” Verghese recalls of the revolution. “I loved Ethiopia. I spoke Amharic fluently, had an Ethiopian girlfriend.” He has never been back.

In the States, Verghese began working nights as an orderly in various New Jersey nursing homes. In 1975 he applied to continue his training at a respected medical school in Madras, India, which accepted him as “a displaced person.” Five years later he returned to America with his wife and their two sons for an internship and residency at East Tennessee State University, then studied infectious diseases at Boston University. In 1985 Verghese moved back to Tennessee, where he worked out of a veterans hospital in Johnson City, a town of 50,000. He had expected to see one or two AIDS patients a year, but soon he was carrying a constant caseload of eighty to a hundred—many of them young gay men. “Actually I was taking care of two diseases: the virus and the shame and embarrassment these young men were experiencing,” he recalls. “After a while I began to feel isolated in town. I was known only as the AIDS doctor, almost as if I were responsible for bringing the illness to Johnson City.”

In 1989, emotionally and physically drained, his marriage suffering from the strain of his work, Verghese left Tennessee with his family and moved to Iowa City, Iowa, where he was accepted in the prestigious University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. “What my AIDS patients were telling me was ‘Live your life. Don’t wait,’” Verghese says. “It may have cost me my marriage.” Within two years he and his wife had separated. (He remarried last October; he met his current wife, Sylvia, in an El Paso AIDS clinic where she was volunteering.) Verghese spent a year and a half in Iowa, earned his master of arts degree, and came under the influence of novelist John Irving, who became his mentor.

Soon Verghese was publishing sharply observed, emotionally wrenching short stories, most of them drawing on his experiences as a doctor. Perhaps the strongest is “Lilacs,” which appeared in The New Yorker in 1991; it recounts the last hours of a young man named Bobby, addled and wandering the streets of Boston, still shaking his fist at an old foe, the implacable AIDS virus. His most disturbing story, “The Agent of His Death Is a White Woman,” ran in The Black Warrior Review the same year and is also set in Boston, among a group of homeless drug addicts. One is a pimply-faced white woman who is desperate to shoot up but can’t because “everything has been hit so many times, the veins are hard as cement and clotted.” A black man named Ndongo takes the dirty needle and assists: “The needle slides into the center of a fat hemorrhoid, and she grunts. Blood spurts out and runs down her leg, but blood also comes rushing back into the syringe, transforming the white fluid to red-black.”

Verghese enjoyed the life of a writer among writers in Iowa and considered staying longer, but he needed what he calls “the workaday world of medicine.” He started looking for a position in academia, and though he had received offers from several major teaching hospitals around the country, he chose El Paso. “I feel my services are needed here,” he says. “Coming back from India or Africa, where I have worked at times, I came to realize that it’s not me they need but money.” By contrast, he sees El Paso as “a First World setting where I can deal with Third World diseases,” a place where patients seem to require his soothing presence and his writer’s willingness to listen almost as much as they need the hospital’s expensive high-tech equipment.

It was his New Yorker editor who urged him to begin work on My Own Country. Newly arrived in El Paso, Verghese would get up each morning at four-thirty to write before going off to his job at the hospital. The result, which took three years to complete, showcases Verghese’s keen powers of perception as well as his fully drawn, real-life characters and finely tuned sense of place. Verghese found that the impoverished trailer dwellers, the uneducated country people, even the fundamentalist preachers in his little niche of Appalachia were often more accepting of the plague victims among them than his professional colleagues were.

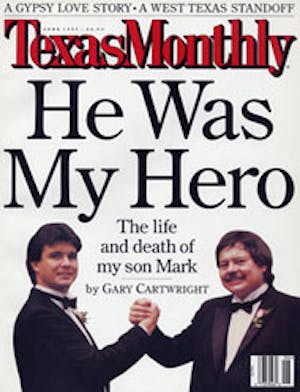

After the success of My Own Country, Verghese planned to resume his fiction writing; he says he likes the control over outcome that often eludes him in the world of medicine. But so far, it hasn’t worked out that way. His second book, The Tennis Partner, grew out of a proposal he wrote for The New Yorker. It’s the true story of a young doctor—a former student of Verghese’s and his best friend—who got hooked on cocaine; after checking into an Atlanta clinic devoted to treating doctors addicted to drugs, he went home, relapsed, and shot himself to death. “It takes place in the world of medical schools and hospitals and medicine,” Verghese says, “but it’s really about male heterosexual friendship. It’s amazing how important male friendships are, but we’re silent about them.”

The Tennis Partner is nearly finished—HarperCollins will publish it in December—but Verghese still has to elbow out time for his writing. His duties as a faculty member can easily overwhelm everything else, so his output isn’t as steady as that of a Rick DeMarinis. It also doesn’t help that Texas Tech bosses aren’t particularly supportive. “The mind-set here is too provincial,” he says. “By and large, I’ve found them pretty unimaginative in the way they’ve used me. I have yet to even give a talk here at Texas Tech. I’m taking a forty percent pay cut to write. My writing just seems to be something they tolerate.”

At least his students seem to appreciate his accomplishments. “He’s so eloquent,” a young woman tells me as we walk down the hall of the hospital. A bearded young man striding along ahead of us overheard our conversation and waited for us to catch up. “Verghese is the reason I’m going to be a doctor,” he says. “I want to be like him.”

It’s easy to see why, as the slender, dark-haired Verghese leads three students on rounds. In one small room a 22-year-old man in blue-and-white pajamas lies in bed on his side, a pillow between his knees. A former dancer at a gay bar in Juárez, he is strikingly handsome, HIV positive, and suffering from testicular cancer that has spread throughout his body. Verghese asks whether he is in any pain, and the patient murmurs no. With a reassuring hand on the young man’s knee, the doctor tells him about chemotherapy and the cocktail of medications he will prescribe to battle the AIDS virus. He answers the young man’s questions, then gently grasps his left hand. “We’re going to fight this thing,” Verghese assures him.

Outside the room the man’s middle-aged mother stares into a mirror, trying to stop crying before she walks in to see her son. When she sees Verghese, she starts crying again. He puts his arm around her and, in Spanish, softly explains the treatment he is prescribing. Her husband doesn’t know their son is sick, the woman says, doesn’t know their son is gay. Verghese and his students answer the mother’s desperate, imploring questions as best they can.

After the morning rounds, Verghese sits at his cluttered desk eating lunch, Batman figures standing guard on the windowsill ramparts. “What’s amazing to me,” he says, “is that there are not more doctor-writers, given the fact that we are privy to the kind of drama we witnessed this morning.” He mentions two doctor-writers he admires, Oliver Sacks and Robert Coles, and his hero, doctor-poet William Carlos Williams, whose patients were mostly working-class people from New Jersey. Verghese believes that, like them, his strength as a physician lies not so much in his medical acumen as in his ability to listen carefully to his patients. “God is in the details,” he says, “in both writing and medicine. When I’m called onto a case, it’s not because I’m better equipped. It’s because I listen to their stories better.”